By David DeJonge

November 11, 2008, marked the 90th anniversary of the end of World War I. Some 4,734,991 American soldiers served in the conflict, and 116,516 Americans lost their lives during the nation’s two-year participation in the war—a casualty rate far surpassing the deaths incurred in the combined wars of Korea, Vietnam, and the Persian Gulf.

In December 2006, I decided to photograph the last American survivors of World War I. With help from independent producer Will Everett, who did an audio special that aired on NPR about the last survivors, and Chris Scheer from the Department of Veterans Affairs, I was able to preliminarily track down 12. By the time I secured financing for my travels, only eight remained.

To complete my project would take 12 months and nearly 30,000 miles of travel. I thought I had completed the project on March 12, 2007, after photographing John Babcock in Spokane, Washington. Shortly after that session, however, I received an e-mail from Robert Young of the Gerontology Research Group, who had discovered a ninth World War I veteran living quietly in San Francisco. Of the nine eventual subjects of my project, only two remain alive at this writing; many died within weeks of their sessions.

James Russell Coffey

(September 1, 1898-December 20, 2007)

My first session was with 108-year-old James Russell Coffey in North Baltimore, Ohio, at Blakely Care Center, on January 18, 2007. Coffey enlisted in the United States Army at the age of 20 in October 1918, just one month before the armistice. He had attempted to enlist before, but he was rejected because his brothers were already fighting in Europe. This rejection didn’t last long, as Coffey returned just two weeks later and was accepted. He served for just two months and was released in December 1918 with the rank of sergeant. Coffey lived alone in a modest room at the center. Stacks of letters from well-wishers and autograph seekers from around the world covered his dresser. The photo session was simple. I hung an antique 48-star American flag behind Coffey and the nurse spoke loudly into his ear: “Russell, open your eyes.” The flash popped and his eyes opened briefly, then relaxed shut again. I discovered the limitations of my project. None of my subjects could stand, few could last for sessions longer than 10 minutes, and most were too far gone to reflect clearly on their memories.

Antonio Pierro

(February 22, 1896-February 8, 2007)

I traveled to Swampscott, Massachusetts, to meet nearly 111-year-old Antonio Pierro. Pierro could not stand, but greeted me with a warm smile and a slow but vintage Italian accent. When the nurse came to check on him, Pierro favored her with another smile and a gracious kiss on the hand. Born in 1896 in Forenza, Italy, Pierro moved to the United States in 1914 and lived in Marblehead, Massachusetts. In 1918 he enlisted in the Army and was sent to France, where he saw action at St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne offensive. For his role in these battles, Pierro was awarded the French Legion of Honor and several other medals.

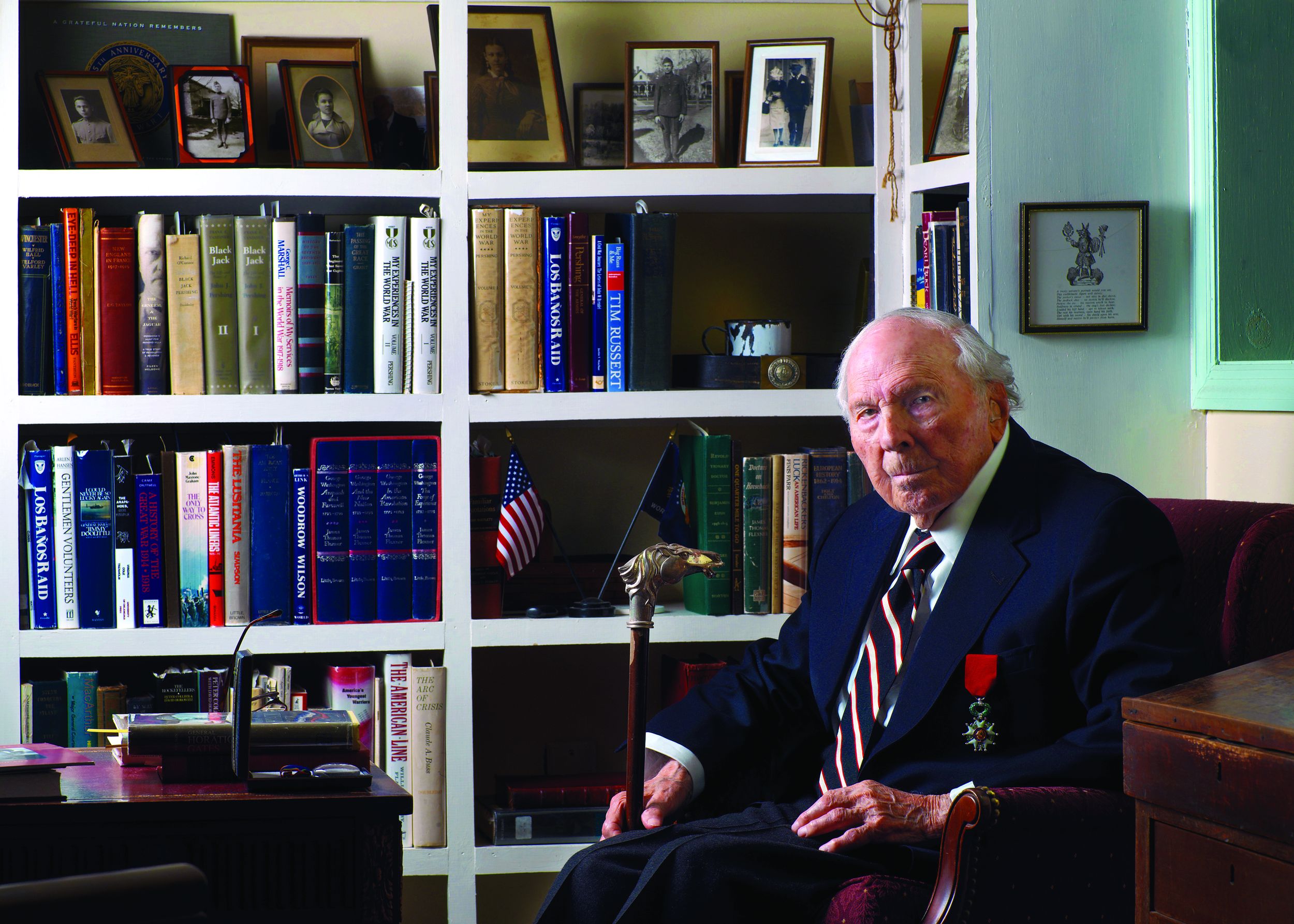

Frank Woodruff Buckles

(February 1, 1901-Present)

Born in Bethany, Missouri, on a small farm, Frank Buckles is the last known American survivor of World War I. Buckles lives in a 300-year-old farmhouse overlooking the battlefields of Antietam and Harpers Ferry. Buckles served in the American Expeditionary Forces as an ambulance driver in France, England, and Germany. He did not see combat, but he did see the terrible aftereffects of the war while transporting wounded soldiers and prisoners of war. As the last known veteran of WWI, Buckles has become a celebrity of sorts, a humble representative of the nearly 5 million who served in the war to end all wars.

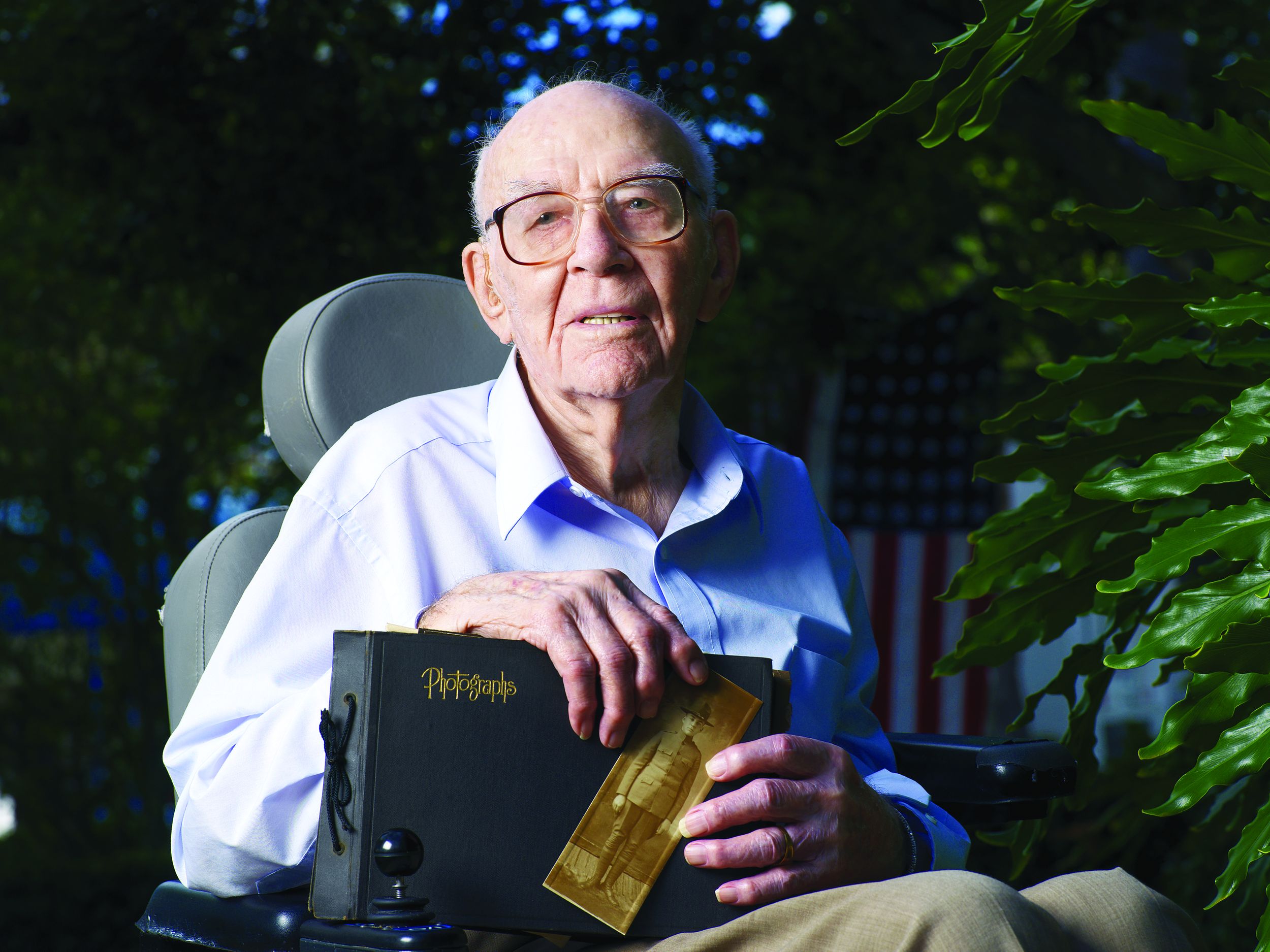

Howard Ramsey

(April 2, 1898-February 22, 2007)

Howard Ramsey was the last American combat veteran who served during World War I. He lived in an adult care home on a quiet street in Portland, Oregon. I arrived and was greeted by his granddaughter Sandy. Seated in a comfortable gray chair was a kind and happy man. At age 109, Ramsey still had a joy for life. He first joined the naval militia during high school and later served on the USS Marblehead, which was one of the ships used by Admiral George Dewey during the Spanish-American War. Being too light to enlist, Ramsey and a friend ate several bananas and drank enough water to gain enough weight to be accepted. While in France, Ramsey encountered a young French girl who asked for a souvenir. He found an American penny and gave it to her. In return, she gave him a small lock of hair wrapped in a tissue. He kept it until the day he died. Since he was one of the few men who could drive a motorized vehicle, Ramsey was put to use teaching others how to drive and also driving ambulances, trucks, and motorcycles.

John Henry Foster Babcock

(July 23, 1900-Present)

Born on a 350-acre farm in Holleford, Ontario, Canada, John Henry Foster Babcock helped on the farm and tapped maple syrup. His father ran a sawmill. Babcock enlisted in the Canadian Army. He served in the Young Soldiers Battalion and recalled marching every day. After being discharged, he made his way to the United States, where he joined the U.S. Army in the 1930s and attempted to reenlist during World War II. He then found out that he was not an American citizen (he thought that you automatically became a citizen while serving in the Army) and became a citizen in 1946. In 2008 he wrote a one-sentence letter to the Canadian prime minister asking for his Canadian citizenship back, which he was granted shortly thereafter.

Harry Richard Landis

(December 12, 1899-February 4, 2008)

One day I got an e-mail about a story that had surfaced in Tampa, Florida, of a WWI veteran who was previously unknown to researchers. I boarded a plane to Tampa and headed off to meet Harry Landis and his wife. Landis enlisted in the United States Army before the armistice and was trained for two months in Missouri prior to the end of the war. He spoke of the Spanish flu pandemic and of having to mop floors at the hospital, where he was exposed to the deadly disease. There was a shortage of uniforms and guns for training, he recalled. When the war ended, Landis drove a car around the town square several times, honking the horn. Later, his battalion did their final march in formation to the girls’ college down the street from their barracks.

Charlotte Berry Winters

(November 10, 1897-March 27, 2007)

Charlotte Berry Winters was born in the nation’s capital in the fall of 1897. She was one of my subjects whose lives incredibly spanned three centuries. When America entered the war in 1917, the United States Navy allowed women to enlist in noncombat roles. Berry and her sister joined the more than 11,000 women in the ranks. Having graduated in 1915 from the Washington Business High School, Winters’s secretarial skills came in handy at the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C. She recalled drilling on the National Mall in Washington. Early in 1917, Winters and her sister met with Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels to discuss women’s roles in the Navy. In June 1919, she and a group of fellow Yeoman (F) veterans organized a club called the Betsy Ross Post No. 1, a service organization for women who were about to be discharged. After the group heard of a similar organization of men doing the same things, Winters’s group merged with the men and formed the American Legion. The Betsy Ross Post later changed its name to honor the USS Jacob Jones and became the second post in the United States.

Lloyd Brown

(October 7, 1901-March 29, 2007)

Lloyd Brown was born in Lutie, Missouri, on October 7, 1901. He lived in Charlotte Hall, Maryland, by himself up to a few months before his death, when his daughter Nancy moved in with him to help. On April 2, 1918, Brown enlisted in the United States Navy. He sailed on the USS New Hampshire, which was assigned to troop convoy escort and antisubmarine duty in the North Atlantic. Under the convoy’s protection, the Navy did not lose one convoy ship to submarine action. Brown recalled his ship capturing a German submarine and sailing up the Delaware River back to Philadelphia. He was amazed at how immaculate the sub was and at her extensive use of brass. Brown reenlisted in 1921 and served aboard the USS Seattle. He later became a Washington, D.C., firefighter and worked at National Airport.

William Seegers

(October 24, 1900-July 10, 2007)

On a sunny afternoon in the winter of 2007, I pulled up to a home nestled in a small side street on the outskirts of San Francisco, where I saw an elderly gentleman drinking orange juice on the porch. At the age of 106, William Seegers recalled being drafted into the German Army at 15. He deserted his unit, but was talked into returning by family members who were afraid he would be executed. Seegers rejoined his unit and was reassigned as a clerk. He offered the only firsthand details of a veteran from inside the former German Empire, describing food shortages and lack of morale as the Allied forces closed in on Germany. Seegers was discharged in 1919. Having witnessed the horrors of war, he later became a member of a socialist colony in Louisiana, where he met his wife, Vinita Thurman. I photographed him clutching his draft papers and American citizenship papers with the American flag and a copy of the Philadelphia Inquirer, where he once worked as a pressman.

As of this writing (January 2009), there are approximately 12 World War I veterans left in the entire world. I recently returned from England, where I photographed the last three veterans, including the world’s oldest veteran, 112-year-old Henry Allingham, the last person to have flown in a biplane during combat, and Harry Patch, the last known trench fighter.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments