By Charles Gutierrez

In December 1944, the Ardennes front or “ghost front” was an area where either veteran Allied units rotated in to rest and recover from terrible combat losses or where new, untested units arrived to gather some combat experience from the minor skirmishes that would occasionally flare up. Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton’s U.S. Army VIII Corps was such a unit.

Three infantry divisions, the 28th, 4th, and 106th, comprised VIII Corps. The 28th and the 4th had been severely mauled in the bloody battles of the Hürtgen Forest. The 106th Infantry Division was newly arrived at the front, replacing the 2nd Infantry Division, and had yet to see combat. The three VIII Corps infantry divisions were responsible for an approximate 88-mile front that was just about three times that normally assigned an equivalent defending force. Although the Germans were on the ropes and expected to capitulate soon, General Middleton still worried about the thin spread of his on such a wide front.

“Don’t Worry Troy, They Won’t Come Through Here”

When General Omar Bradley, 12th Army Group commander, visited Middleton at his headquarters in Bastogne, Middleton expressed concern about the overall defensive situation, only to be told, “Don’t worry Troy, they won’t come through here.” Middleton replied, “Maybe not, Brad, but they’ve come through this area several times before.” To help assuage his fears, General Bradley provided VIII Corps with the newly arrived 9th Armored Division.

Major General John W. Leonard’s 9th Armored Division was, like most armored divisions of the period, divided into three separate combat commands (CC): A, B, and R (Reserve). Each combat command was a combined arms military organization of comparable size to a brigade or regiment and loosely patterned after the German combined arms approach to mechanized warfare. Each combat command usually consisted of one armored battalion and one armored infantry battalion. In addition, smaller units of tank destroyers, engineers, and mechanized cavalry were assigned as needed to accomplish any given mission.

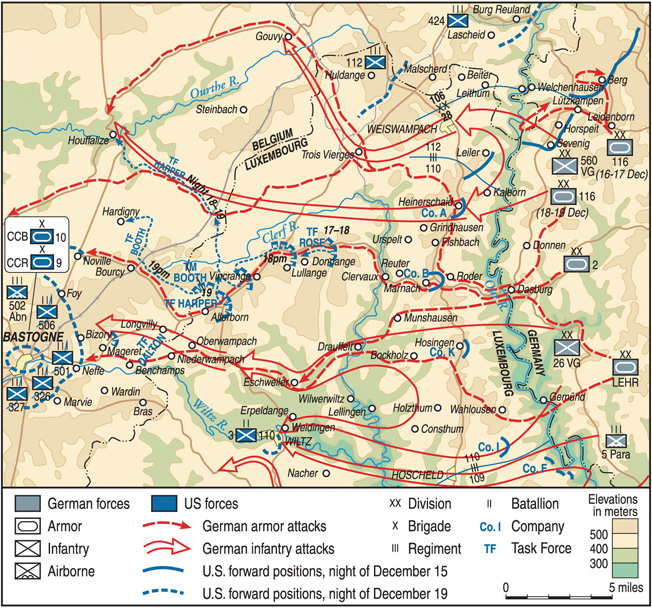

In mid-December 1944, the three combat commands of the 9th Armored Division were scattered throughout the Ardennes front. CCA was placed just south of the confluence of the Our and Sure Rivers wedged between the 109th Infantry Regiment of the 28th Infantry Division to its north and the 12th Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division to its south. CCB found itself near the village of Faymonville and recently attached to V Corps to support the U.S. Army’s effort to capture or destroy the Roer River dams. CCR, under the command of Colonel Joseph H. Gilbreth, was stationed at Trois Vierges, roughly 20 miles northeast of the crossroads town of Bastogne, Belgium, in support of VIII Corps’ left and center.

Operation Watch on the Rhine

Unknown to the Americans, the Germans were planning a major offensive code-named Operation Watch on the Rhine. According to the German plan, the offensive would cut across the Ardennes front, capturing Bastogne, one of three critical communication/road network centers in Field Marshal Hasso von Manteuffel’s Fifth Army sector. The other two were St. Vith to the northeast and Marche-en-Famenne to the northwest. Thus, Bastogne, like St. Vith and Marche-en-Famenne, needed to be dealt with quickly to achieve Hitler’s goal of capturing the Belgian port city of Antwerp and splitting the Allies—both politically and geographically.

Bastogne lay in the sector of advance that Manteuffel assigned to XLVII Panzer Corps and its commander, General Heinrich von Luttwitz. General Luttwitz’s corps consisted of the 2nd Panzer Division, the Panzer Lehr Division, and the 26th Volksgrenadier Division (VGD) with the added strength of the 15th Volks Werfer (rocket launcher) Brigade, the 766th Volks Artillery Corps, the 600th Army Engineer Battalion, and the 182nd Flak Regiment.

Manteuffel’s instructions to Luttwitz were direct: “Panzer Lehr Division holds itself ready to advance by order of the corps following behind the 26th VGD by way of Gemund-Drauffeld toward Bastogne and the Meuse in the sector of Namur-Dinant. It is essential for the division to take up positions … close to the 2nd Panzer Division advancing over Noville. In the case of strong enemy resistance, Bastogne is to be outflanked, its capture is then up to the 26th VGD….”

Since the primary mission of the Fifth Panzer Army was to reach and cross the Meuse River by day three of the offensive in flank support of Sixth SS Panzer Army’s drive to capture Antwerp, the 2nd Panzer and the Panzer Lehr Divisions were to rapidly move beyond Bastogne regardless of who held it.

The area of the Ardennes designated for the XLVII Panzer Corps’ breakthrough was held by the 28th Infantry Division’s 1st and 3rd Battalions of the 110th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Hurley F. Fuller. Fuller’s regimental front stretched approximately 10 miles, and anything even remotely resembling a continuous line of defense was far beyond the manpower capabilities of the 1st and 3rd Battalions. The best that could be done was a system of village strongpoints, each defended by troops in the approximate strength of a rifle company. The 26th VGD commander, General Heinz Kokott, was given the mission of forcing crossings at the Our and Clerf Rivers on the left of the Panzer Corps, holding them open for the armor of the 2nd Panzer Division, then following it to Bastogne. Panzer Lehr would follow directly behind the 26th VGD. Once Bastogne was secured, the 26th VGD would be responsible for covering the left flank of the Panzer Corps, allowing the two armored divisions to cross the Meuse unmolested.

To Slow the German Advance

In the early morning hours of December 16, 1944, all along the Ardennes front from Monchau in the north to Echternach in the south, American forces awoke to the sound of German artillery. In the 9th Armored Division’s CCR sector, the 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion seemed to be the primary target of the shelling. Lt. Col. Robert M. Booth, commander of the 52nd AIB, was informed at a midday briefing that there was nothing to worry about. The entire front was being subjected to similar bombardment, and the Germans were probably just putting on an artillery show or involved in some spoiling operation.

With reports of German assaults and penetrations coming in throughout the day from his entire VIII Corps sector, General Middleton realized that what was occurring was no simple spoiling attack but a major German offensive. Middleton understood that with the number of enemy units involved and with the speed at which they were attempting to move they would need more road available. Middleton therefore planned to hold his original VIII Corps positions as long as possible while building strong defenses in front of the road network hubs of St.Vith, Houffalize, and Bastogne. It was Middleton’s reasoning that a strong American concentration within these transportation centers would force the Germans to come to him and, in any case, American forces would be in strength on the enemy’s flank and rear. On December 16, however, the forces available to Middleton to implement this plan were not nearly enough.

Middleton conferred with his immediate boss, Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges, commander of First U.S. Army. Hodges agreed with Middleton’s assessment, and on the morning of December 17, Hodges was trying to reach General Bradley to have the only two SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) reserve divisions left on the European continent, the 101st and the 82nd Airborne divisions, released to VIII Corps for the immediate defense of Bastogne. Almost immediately after speaking to General Hodges, General Bradley put in a call to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander, requesting the release of the two reserve airborne divisions. It was not until 7 pm on December 17 that Eisenhower, reluctant to part with his last reserve divisions, gave permission.

Middleton, believing that he would eventually be granted the two reserve divisions, still had one major problem: how to slow down the German advance long enough to allow for the arrival and deployment of the paratroopers. Aside from a couple of engineer units, Middleton had only one combat unit in reserve and that was the newly arrived and untested 9th Armored Division. Moreover, because of the breadth of the German assault he could not even use the entire division in the Bastogne sector. CCB of the 9th Armored was immediately needed in St. Vith to shore up the 106th Infantry Division, while CCA was badly needed in the Wallendorf-Echternach area to support the 4th Infantry Division. Essentially, the only uncommitted combat unit he had left was CCR of the 9th Armored Division.

Bastogne: Key to the Southern Ardennes

By midday on December 17, Luttwitz’s 2nd Panzer Division, after crushing American resistance in Marnach, was pushing west toward Clervaux and its bridges across the Clerf River. The Clerf crossings lay only about 17 road miles from Bastogne. The German advance toward Bastogne took on an added urgency when, during late evening of the 17th, Fifth Panzer Army headquarters intercepted an Allied command message ordering the two American airborne divisions to Bastogne.

General Manteuffel had planned that Bastogne would be taken on the first day of the offensive. Although unexpected stiff pockets of American resistance had delayed Bastogne’s capture by at least a full day, all was far from lost. Manteuffel and Luttwitz believed that the two airborne divisions would reach Bastogne either during the night of December 18 or early on the 19th. Once Luttwitz’s XLVII Panzer Corps crossed the Clerf, Bastogne could be reached no later than midday of the 18th, thus allowing German command and control the use of its vital road network.

Control of Bastogne would not only ensure an easier and swifter advance toward the River Meuse but would also ensure firmer control of the entire southern Ardennes region. Although the plan called on German armor to bypass Bastogne should immediate capture prove unfeasible, investment would still tie down German forces needed elsewhere. In addition, an American occupation of Bastogne would provide Allied forces with a base from which to hamper the German flanks and rear as well as cause major resupply problems for Luttwitz’s fuel-hungry tanks. The Germans did not expect this to happen.

At about 9:40 am on the 17th, approximately 10 minutes after word came that the Germans had captured Clervaux and crossed the Clerf River, General Middleton ordered Colonel Gilbreth to establish two roadblocks between Clervaux and Bastogne in an effort to delay the Germans. Colonel Gilbreth’s Combat Command R consisted of the 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion, the 2nd Tank Battalion, the 73rd Armored Field Artillery Battalion, the 811th Tank Destroyer Battalion, and other conventional task force attachments. However, prior to Middleton’s roadblock order, desperate fighting on the morning of the 16th by elements of the 28th Infantry Division had already drawn off portions of Colonel Gilbreth’s command. The 112th Infantry Regiment drew off a platoon of tank destroyers, and the 110th Infantry Regiment was sent a platoon of tank destroyers as well as a company of tanks.

Combat Command R, unlike its two sister combat commands within the 9th Armored Division, would not be given a chance to prove itself as an independent unit in combat. The decisions about where to place CCR’s individual components were to be made elsewhere— some by Maj. Gen. Norman Cota, commanding the 28th Infantry Division, some by his regimental or battalion commanders, and some even by the corps commander himself. Colonel Gilbreth would have very little independent command and control over his unit. CCR would be treated as a true reserve force from which units and men could be drawn as needed, a holding unit for a heterogeneous collection of troops and equipment. Colonel Gilbreth’s as yet untested command, within this framework of parceling, separation, and external control, was expected to stop the advance of a formidable Wehrmacht armored division.

“The Battle Must be Fought With Brutality”

Luttwitz’s 2nd Panzer Division was formed in 1935. Its first commander was General Heinz Guderian, the father of the Blitzkrieg tactic. Prior to its participation in the Ardennes offensive, the division participated in the invasions of Poland, France, the Balkans, and Russia. It was the first German division to reach the Atlantic and the first to reach the Swiss frontier. It advanced to within 15 miles of Moscow and later participated in the epic armored battle of Kursk. Prior to its commitment to the Ardennes offensive, 2nd Panzer was supplied with the newer model Panther medium tanks equipped for night fighting with the new infrared sighting apparatus and high-velocity 75mm cannon. Its two tank battalions were about at full strength with 27 Mark IVs, 58 Panthers, and 48 armored assault guns.

Also, within hours of the division’s commitment to battle, it was appointed a new commander, Colonel Meinrad von Lauchert. The German high command felt that its former commander, General Henning Schonfeld, lacked the aggressive spirit required for the forthcoming offensive. A half hour prior to the launching of the Ardennes offensive, Colonel Lauchert received a personal phone call from Hitler instructing him that in directing his forces, “The battle must be fought with brutality and all resistance shall be broken in a wave of terror.”

In compliance with Middleton’s order, Colonel Gilbreth established two roadblocks. The first and northernmost was at the intersection near the village of Lullange where the road from Clervaux entered Highway N-12. Clervaux was only a scant five miles from this junction and only about 13 road miles from Bastogne. The second roadblock was at a junction where a secondary road from the valley of the Clerve at Drauffelt joined Highway N-12 near the village of Allerborn. This second roadblock was only about eight miles from Bastogne. Middleton ordered that these two roadblocks be held “at all costs.”

Task Force Rose, Task Force Harper, and Team Booth

CCR, 9th Armored was now split into two task forces. The northernmost roadblock near Lullange, under the command of Captain L.K. Rose (Task Force Rose), consisted of a company of Sherman tanks (A Company, 2d Tank Battalion), one armored infantry company (C Company, 52nd AIB), and a platoon of armored engineers. The second roadblock near Allerborn, under the command of Lt. Col. Ralph S. Harper (Task Force Harper), consisted of a company and a half of Sherman tanks (C and D Companies, 2nd Tank Battalion), one company of armored infantry (B Company, 52nd AIB), and a platoon of armored engineers. What was left of CCR was placed under the command of Lt. Col. Robert M. Booth (Team Booth) and occupied the high ground immediately north of Allerborn. It consisted of a company of armored infantry (minus one platoon), one platoon of tank destroyers, and one platoon of light tanks and had the mission of protecting the left flank and rear of Task Force Harper. CCR’s 73rd Armored Field Artillery provided artillery support from a small village called Buret just northwest of Task Forces Rose and Harper.

Captain Rose placed a platoon of infantry facing north of the junction and another platoon facing east on the road coming from Clervaux. All three platoons of his tank company (15 Sherman tanks) were positioned about 300 yards to the rear of the infantry. At approximately 8:30 am on December 18, the infantrymen of Task Force Rose facing Clervaux reported that three enemy tanks accompanied by infantry were approaching. Approximately a half hour later the tankers saw the three German tanks emerge from the cover of the woods. These enemy tanks and infantrymen belonged to the reconnaissance battalion of Colonel von Lauchert’s 2nd Panzer Division whose infantry elements were eliminating the last of the American defenders in Clervaux. The Sherman tanks of A Company opened fire and counted hits on all three German tanks. Due to German superiority in armor, however, only one enemy tank was disabled while the other two turned back for cover.

Shortly after this initial engagement, four enemy tanks supported by infantry emerged from the woods just northeast of the American forward positions. A few minutes later an entire German tank column barreled down on Task Force Rose from the north. The enemy tanks first turned their guns on Task Force Rose’s armored infantry posts, forcing the infantrymen to withdraw to the Shermans. As the lead panzer came into view, it was turned back by fire from the American tanks.

Advancing Through Smoke

To assist with the destruction of enemy armor, Captain Rose called for artillery support on the Germans’ suspected assembly area. While the 73rd Armored Field Artillery (AFA) was busy shelling suspected enemy assembly points, the Germans were busy bringing up their own artillery. After a brief shelling of Task Force Rose positions, the German guns placed a smoke screen in front of the American task force. After about 15 minutes the smoke cleared with no immediate action on the part of the Germans. The German reconnaissance battalion was still carefully feeling out this rather unexpected mix of enemy armor and infantry and had decided to wait for the arrival of the main body. At about 11 am, the first Mark IVs of the 2nd Battalion, 3d Panzer Regiment appeared.

Within minutes after the arrival of the its 2nd Battalion, 2nd Panzer artillery shelling started to pick up once again and another smoke screen was laid down in front of the Americans. This time it took nearly 90 minutes for the smoke to lift, and when it did the GIs of Task Force Rose discovered that the German panzers had moved to within 800 yards of their position and the Shermans were taking direct fire from approximately 16 German tanks. In addition to the direct fire coming from the German panzers, the infantry and Shermans of Task Force Rose were also coming under indirect fire from 88mm antiaircraft guns estimated to be about 2,500 yards to the east. The time was about 1 pm on December 18. According to Lauchert’s timetable, his reconnaissance battalion should have been in Bastogne well over an hour earlier.

In the exchange of fire, A Company knocked out three Mark IVs with one Sherman destroyed, the main gun of a second was disabled, and a third Sherman threw a track, forcing its crew to destroy it. While Task Force Rose’s complement of Shermans was slowly dwindling, 2nd Panzer Division tanks kept multiplying as more of the division rolled up from Clervaux. The sounds of enemy tanks could be heard to Task Force Rose’s right, and since the armored infantry’s antitank platoon could not cover the task force’s right flank, a platoon of Shermans was dispatched. The Shermans came upon three enemy tanks, one of which was quickly destroyed with the other two withdrawing into defilade. One Sherman became bogged down in the mud and had to be evacuated.

Since the bulk of 2nd Panzer was coming up from the east along Highway N-12, the bulk of Task Force Rose was facing east. This left only one tank platoon to defend to the north. Realizing this, the German commander shifted his force to allow a stronger attack to the north and northwest of the Americans. Task Force Rose’s commander, seeing that his command was quickly dissolving against the overwhelming strength of the enemy, dispatched two Shermans along Highway N-12 to the Allerborn roadblock along with a plea for immediate assistance. The two Task Force Rose Shermans would be able to lead reinforcements back and guide them into position.

The Collapse of Task Force Harper

At the Allerborn roadblock Task Force Harper was then in command of Major Dalton, the executive officer of the 2nd Tank Battalion. The sound of battle had not been lost on the Allerborn defenders, and when the tanks of Task Force Rose showed up with the disturbing news of the desperate fight just up the road, Major Dalton immediately dispatched an assault gun platoon and a platoon of Shermans under the command of Captain Baird, the Battalion’s S-3. However, no sooner had Captain Baird’s force started to move out when Lt. Col. Harper appeared and canceled the mission. As much as Harper wanted to assist Task Force Rose, Middleton was not allowing him independent control of Task Force Harper, and Middleton would not allow any part of Task Force Harper to assist Task Force Rose. The two Shermans sent by Task Force Rose to lead the relief force had to return alone to the battle.

At approximately 2 pm, Task Force Rose’s supporting artillery at Buret came under fire from German tanks emerging from the northeast. These enemy forces were the lead elements of the 116th Panzer Division, which were on their way to Houffalize after taking Trois Vierges. The 73rd AFA batteries were immediately pulled back to Longvilly.

Also at about 2 pm, Colonel Gilbreth called General Middleton to request permission to withdraw Task Force Rose from the Lullange roadblock and move it back to the Allerborn roadblock. Middleton not only refused to assist Task Force Rose, but he further refused to let it retreat south. The do-or-die circumstance meted out to Task Force Rose at Lullange exemplifies the desperate situation facing VIII Corps command during the first days of the offensive. With only a few troops, tanks, and tank destroyers available to VIII Corps to stem the German onslaught, Middleton believed that only through total commitment and sacrifice would his scant forces be able to hold off the far superior Germans until such time that SHAEF could muster enough strength to permanently repel the invaders. At approximately 3 pm on December 18, CCR headquarters at Longvilly received the final message from the northern roadblock that the defenders had been overrun.

Next, the Germans turned their attention to Task Force Harper near Allerborn. Although the advance elements of the German assault reached the southern roadblock in late afternoon it was not until after dark that the Germans launched their first major attack. In the opening onslaught, the Germans swept the first line of defense with machine-gun fire to clear out any infantry that might be protecting the tanks. After this, the Mark IVs and Panthers destroyed two tank platoons of Company C, 2nd Tank Battalion as well as a number of infantrymen being silhouetted by the burning vehicles. The German tanks were effectively aided by their infrared night-sighting devices with an effective range of 400 meters. By 9 pm, Task Force Harper ceased to exist as a unified, cohesive fighting unit. Lt. Col. Harper ordered the survivors to fight their way to Longvilly.

Reorganizing the Defensive Line

Harper, finding his way to Longvilly blocked, headed cross country with an assault gun platoon in the direction of Houffalize where, along the way, he met up with a retreating body of Task Force Rose tanks and soldiers directed by a Lieutenant DeRoche. Harper ordered five of DeRoche’s Shermans to remain with him and sent DeRoche with what was left to St. Hubert for fuel and ammunition. Harper next tried to set up a defensive line at Houffalize to stop the Germans and during the night engaged the forward elements of the 116th Panzer Division. In the ensuing battle, Harper was killed and his scratch force of armor and infantry cut to pieces.

The 116th Panzer Division logs for this date report a number of skirmishes with American armor. Just after midnight, in a message to its corps headquarters, 116th Panzer reported heavy resistance and the taking of prisoners from the American 52nd Armored Infantry Battalion. Although the 116th Panzer Division was making progress against stiff and unexpected opposition, its corps headquarters was unhappy with its slow progress and the commanding general of the 116th Panzer was instructed to assume personal leadership of his advance elements. The corps commander informed his division commander that the order came down from the highest level of command.

In Longvilly, Colonel Gilbreth and the remnants of Task Forces Rose and Harper waited for the expected arrival of the enemy force that had annihilated his two roadblocks; however, it was nearing midnight on December 18 and still there had been no direct assault upon their position. The reason for the reprieve was that the 2nd Panzer Division, in keeping with the XLVII Panzer Corps operational plan, turned off the main road, bypassing Bastogne to the north and heading for the Meuse River. Shortly after midnight, Gilbreth ordered his forces to prepare to withdraw to Bastogne. At about the time Colonel Gilbreth was readying his force to withdraw, the first units of the 101st Airborne Division began arriving in the assembly area near Bastogne and, before night fell again on the 18th, the 101st Airborne would have all four regiments unloaded from their trucks and deployed in and around Bastogne.

The Retreat to Bastogne

With its primary mission now canceled with the destruction of Task Force Harper, Team Booth weighed its options of either defending in place or heading for Bastogne. Lt. Col. Booth’s outposts had reported the presence of enemy armor on the Bourcy-Noville road and a platoon of the 52nd AIB discovered enemy units to the west, northwest, and south. Based upon all available information, Booth estimated that his team was up against at least one armored division. On the morning of December 19, Booth decided to move what was left of his team plus about 100 stragglers, even a few from the 106th Infantry Division, to Bastogne.

Lieutenant DeRoche, after turning five of his Shermans over to Lt. Col. Harper, led his small force toward St. Hubert where they found supplies of fuel and ammunition. After stocking up, the DeRoche force proceeded to Neufchateau where General Middleton had relocated his command post. Once in Neufchateau, DeRoche located Captain Walter M. Meier, who was busy gathering and regrouping retreating CCR men and armor. After acquiring DeRoche’s small force and a few others, Captain Meier called 9th Armored Division headquarters in Mersch and received permission to take his force into Bastogne.

Captain Meier’s force, like most of CCR, 9th Armored and 28th Infantry Division soldiers and tankers retreating from the roadblock battles, eventually made it to Bastogne. However, many other retreating soldiers never made it, having fallen to the gauntlet of sporadic enemy artillery fire, snipers, and engagements with concealed enemy infantry and tanks. Men and armor retreating into Bastogne from the battles that preceded the arrival of the 101st Airborne Division continued to stream in throughout the day with valuable information concerning German deployment and strengths.

These retreating soldiers and tankers were not, despite some postwar accounts, a bunch of dispirited, demoralized, and undisciplined panic mongers. The great majority of these men had given it their all. They came through the 101st defensive lines having had very little sleep or food for three days and in almost constant battle with an enemy that not only had the full advantage of surprise but was also far superior in numbers, the quantity and quality of its armor, and in its battle experience. The personnel of CCR, 9th Armored Division who managed to make it to Bastogne and regroup were able to assist the 101st Airborne Division by acting as either mobile emergency relief strike forces, armored support for the lightly armed paratroopers, or direct infantry augmentation to the defense line.

After the war, General Manteuffel wrote: “On the whole the delaying action of the withdrawing American Army was a success. It slowed down the German advance, though it could not prevent the pursuing German spearheads from coming within 4 km from the Meuse near Dinant without any major engagements. But the resistance by delaying actions gained the time needed to bring up their tactical reserves at the correct moment.”

Cell is the name of the village where the Germans stopped and walked back to Germany. My mom worked for American Red Cross, were she met my father an American Engineer. I was born in Dinant, Belgium.

My grandfather Eugene Orlowski was in the 9th armored div. Waiting for his service records. Great information here.

My father was in Team Harper, I do not know exactly what happened after Allerborn, though he survived and came home,

My dad was in A company 2nd tank battalion he had great respect for lieutenant DeRouche