by Michael Haskew

“Japan cannot defeat America; therefore, Japan should not go to war with America.” Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the Combined Fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy, spoke those words to a group of school children as his government contemplated just that.

[text_ad]

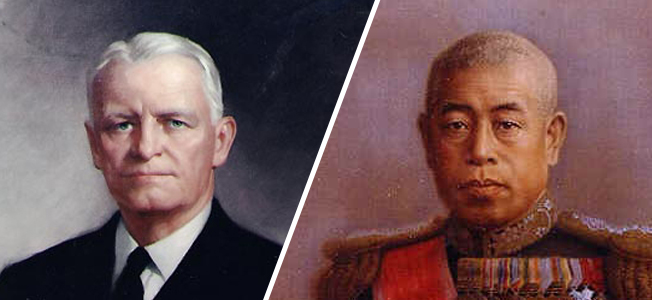

The pragmatic Yamamoto, 57 years of age and a career naval officer who graduated from the Imperial Naval Academy at Etajima in 1904 and lost two fingers on his left hand during the great victory over the Russian Baltic Fleet at Tsushima in 1905, was well acquainted with the United States. He had traveled to the U.S. during the 1920s, served as a naval attache in Washington, D.C., and studied at Harvard University. He was a gambler, and he loved to play bridge. He was also well aware of America’s tremendous industrial capacity and knew that Japan could not hope to prevail in a protracted war for preeminence in the Pacific and the Asian mainland.

An Early Sprint Their Only Chance

Nevertheless, when the Japanese government charted a course to ignite World War II in the South Pacific, Yamamoto did his duty, planning the attack on Pearl Harbor and then conceiving the offensive that led to the fateful Battle of Midway. Yamamoto was spurred on by his realization that victory had to be won swiftly. He once said to a colleague in the frankest of terms, “If I am told to fight regardless of the consequences, I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have utterly no confidence for the second or third year.”

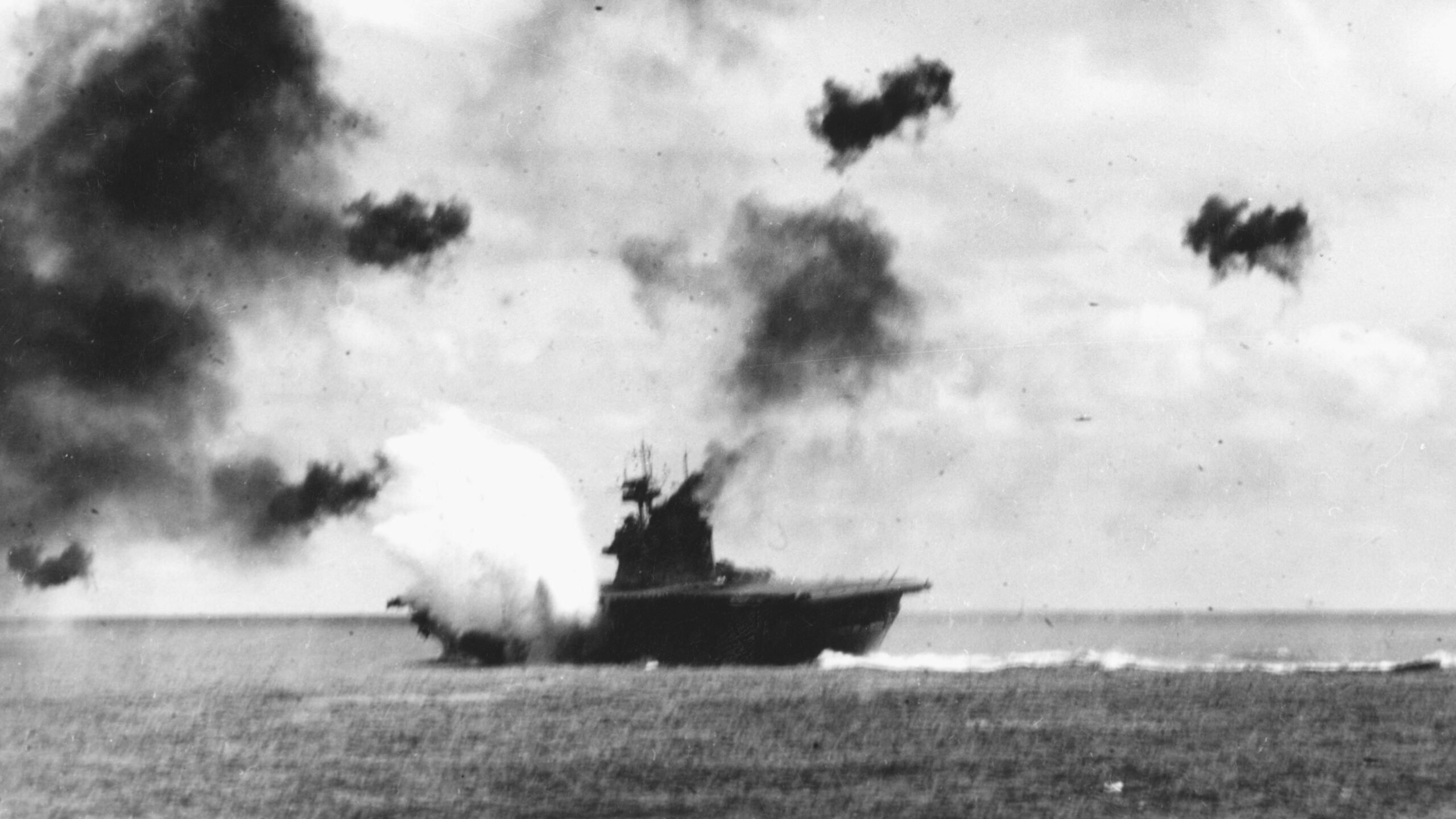

In keeping with his sense of urgency, Yamamoto intended to take full advantage of his temporary superiority in aircraft carriers, trained pilots, and state-of-the-art carrier-based planes. The seizure of Midway, a tiny atoll approximately 1,100 miles from Pearl Harbor, would threaten Hawaii with invasion and expand the Japanese defensive perimeter in the Pacific substantially. At the same time, the Japanese Navy would draw the weakened American naval presence in the Pacific into a major battle, sink the enemy’s carriers, and compel the United States to sue for peace.

True to form, Yamamoto hatched a complicated plan for the Midway operation, involving a feint toward the Aleutian Islands thousands of miles to the north along with a division of his forces headed to the vicinity of Midway from multiple directions.

Cracking the Japanese Naval Code

Yamamoto’s opponent was Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, who assumed command of the shattered U.S. Pacific Fleet just three weeks after the Pearl Harbor disaster. Born in Fredericksburg, Texas, the 57-year-old Nimitz graduated seventh in the U.S. Naval Academy Class of 1905. He commanded destroyers and cruisers during World War I and the interwar years.

While Yamamoto schemed from a position of strength, Nimitz was seriously weakened. One advantage Nimitz possessed was the intelligence gleaned from cryptanalysts who had cracked the Japanese naval code, JN-25B, and determined that during the first week of June 1942, the Japanese planned to move in force against Midway.

Nimitz wrestled with his command options. He had to defend Midway, but to do so meant risking his precious carriers, only three of which, Yorktown, Hornet, and Enterprise, were operational at the time. In the face of overwhelming odds, his even temperament and quiet optimism compelled him to accept the possibility of survival or the unthinkable catastrophic failure.

The Battle of Midway, June 4-7, 1942, proved to be the turning point of the Pacific War. For the loss of Yorktown, four Japanese carriers, Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu, were sunk. Both Yamamoto and Nimitz staked everything on the outcome at Midway, one of them an inveterate gambler whose prediction of the course of the war was eerily prophetic while the other exhibited steely nerve with his navy’s back against the wall.

Yamamoto did not live to see the eventual downfall of Japan. His plane was shot down by American fighters over the island of Bougainville in February 1943. Fleet Admiral Nimitz is revered today as one of the principal architects of the Allied victory in World War II. He died in 1966 at the age of 80.

Originally Published September 14, 2015

Indeed, Yamamoto was certainly proven correct.