By Christopher Marks

Lieutenant Harold Gilson Payne, Jr., was one of the first Americans to die at Iwo Jima. He did not fall in the carnage of the Marine invasion that began on February 19, 1945. Hal Payne died eight months earlier, on June 15, 1944, in the backseat of my father’s plane a few hundred feet over the island.

My father, David A. Marks, died in 1990 at the age of 73. As I went through his papers I found a small, wrinkled photo in his wallet. Dad was on the deck of an aircraft carrier, in his mid-20s, shaking hands with a fellow over a bomb. He sported a broad smile, a smile I had seen rarely in our 33 years of life together.

I flipped it over. There, in Dad’s handwriting, it read, “With Hal Payne—just fooling around!” I had not seen many pictures of dad when he was young, and this was a nice one. I slid the image into the plastic sleeve of a photo album and moved on. Fourteen years later, I decided to find out who Hal Payne was, and why his picture was in Dad’s wallet.

Lieutenant Hal Payne of VT-32

Dave Marks was a career naval officer, graduating from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1940. He had been a young ensign aboard the battleship USS Maryland during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and had seen dead classmates floating in the oily water. Impressed with the display of enemy air power, he spent the next two years back in the States becoming a naval aviator, a term he always pronounced with great pride. In late December 1943, he reported aboard the aircraft carrier USS Langley in San Diego, a spare 35 minutes before she left for the Pacific and the war. He was assigned to the torpedo bomber (VT) section of Air Group 32, flying Grumman TBF Avengers. Lieutenant Hal Payne was VT 32’s Air Combat Intelligence (ACI) officer.

Hal had come to the war and VT 32 in a typical yet less professional way. A 1933 graduate of Dartmouth College, he had been doing something else with his life when America entered the war. He had been a successful cosmetics and perfume salesman based in Washington, D.C., with a large territory in the Mid-Atlantic states. Along the way he met and fell in love with Francine Theureau, a French native and Sorbonne graduate. They were married on New Year’s Eve 1935. Along with millions of other Americans, Hal Payne volunteered to risk his life and serve his country.

An essential part of Payne’s job as VT 32’s ACI was to debrief the pilots in the ready room immediately after each strike mission. Memories were still fresh in the pilots’ minds, and the adrenaline was still coursing through their systems. What did your bombs hit? What was the antiaircraft fire like? Did you encounter enemy planes? What tactics did they use? Are there more targets we need to hit again? What was the weather like?

These were just some of the questions he posed to each pilot. Taking notes in longhand, Hal typed them up on a Navy form titled “Aircraft Action Report.” Today, these reports reside in the National Archives.

But Lieutenant Payne did not confine himself to postmission ready room interviews and typed reports. He wanted to see action. Payne frequently hitched rides on strike missions, usually bringing a bulky camera along to take reconnaissance photos. He nestled himself in the “greenhouse” compartment of the Avenger, a few feet behind the pilot under a glass canopy. Originally designed to hold a second pilot or a navigator, the small space was partially filled with electronic gear. It was where Hal Payne spent the last hours of his life on June 15.

Mission to Iwo Jima

Nine days earlier, Allied forces had stormed ashore in Normandy. Rome had fallen. Two million Soviet soldiers stood poised for a summer offensive that would carry them to the German border. In the Pacific, the island hopping strategy was at a critical stage. Two islands in the enemy-held Marianas chain, Saipan and Tinian, were coveted by American war planners. They were ideal launching bases for the new Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers starring in the upcoming air campaign against the enemy’s home islands. But first, they had to be taken—taken from Japanese garrisons with no hope of survival or escape and no thoughts of surrender. The Marines invaded Saipan on June 15.

Six hundred miles to the north lay a little speck of volcanic rock called Iwo Jima. It had been an important stepping-stone for Japanese air power early in the war. There were two airfields on Iwo, and the Americans sought to keep enemy planes there from assisting their cornered countrymen on Saipan. Several American aircraft carriers were detached to strike Iwo as the Marines established their Saipan beachead. The Langley was one of those carriers.

The pilots of Air Group 32 were filled with considerable anxiety over the Iwo mission. They had lost one of their most popular flyers in a fighter sweep over Saipan on June 11. Tokyo was only 600 miles to the north, and this was the first American carrier strike against prewar Japanese soil. Iwo was thought to be brimming with the legendary Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters. As if that was not enough, the weather was terrible. The carrier was on the outer edge of a typhoon. Emil Sellars and Vernon Cravero, the two enlisted aircrewmen in Dad’s plane, warned Lieutenant Payne not to go. It was going to be a bad mission, they said. Stay here on the ship. Play it safe. Evidently my father disagreed, and Hal Payne climbed aboard.

The Langley’s eight Avengers launched from a pitching flight deck at 2 pm, about 150 miles east of the island. They carried 500-pound bombs and a mix of incendiary and fragmentation clusters. After joining up with dozens of planes from other carriers, the aerial armada headed west. Seventy-five miles from the target they ran into an impenetrable weather front. The force broke up into two groups to get around it. One went north and the other south, including all the Langley planes. The northern group found an opening first and raced through it to Iwo. The southern group came back to the north and found the opening after 125 miles of additional air travel. They arrived over the hornet’s nest at 4:30 in the middle of an ongoing battle.

Hal Payne’s Last Flight

The first two Langley Avengers found a hole in the cloud cover and pushed over from 9,000 feet. Their target was Motoyama Airfield No. 2 in the center of the island. Its runway was ringed with a seemingly endless array of antaircraft guns manned by angry, alert men with plenty of ammunition. The pilots put the runway in their sights and began their steady, 35-degree glide to the target. Steady was good for the American bomber pilots, but it was also good for the Japanese gunners.

Amid accurate and intense antiaircraft fire, the pilots released their bombs. They were believed to have fallen on the center of the runway. The actual points of impact were estimated because the pilots were too busy escaping with their lives to look at the ground. Sellars and Cravero had been right.

The third Avenger was flown by Dave Marks, with Hal Payne right behind him in the greenhouse. “Between 3000 and 2500 feet in a 20 degree angle glide,” the Aircraft Action Report stated later, “Lieut. Marks released 4 500-pounders which were believed to have fallen diagonally across the northern 2/3 of the runway.” The Japanese gunners were waiting. “Just as his bombs went out, Lieut. Marks right wing and port elevator were hit by 40 mm. AA making the exact location of his drops impossible” to observe.

The right side of the fuselage and the bomb doors were shredded by 40mm shell fragments and .50-caliber bullet holes. In the flash of an eye, a shell went through the trailing edge of the right wing and exploded, sending chunks of shrapnel into the greenhouse. One piece tore though Hal Payne’s right chest and exited the left side of his back. He crumpled to the deck, his face contorted in agony. Desperate to help in some way, a crewman crawled to the injured man and stabbed a shot of morphine into Payne’s chest. Within moments, Hal’s face slackened and he died.

All of the Langley Avengers were damaged in their pass over Motoyama No. 2. An aircrewman, Arnold “Blackie” Marsh, was shredded and killed in Lieutenant (j.g.) George Winn’s plane. Winn’s canopy was completely shot away, and he was sitting out in open air.

Pilot Pat Patterson was nearly blinded by flying glass when enemy bullets struck home in his plane. He was kept conscious only by ammonia soaked handkerchiefs passed forward by his crewmen. But the Avengers were sturdy planes flown by experienced pilots. They headed home, some in pairs, helping each other stay aloft with encouragement and guidance.

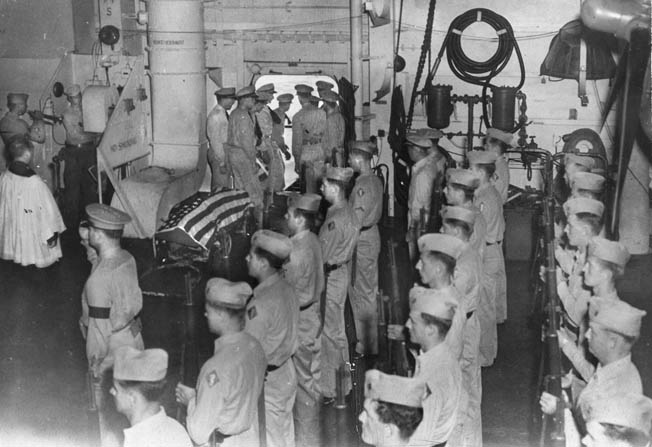

Burial at Sea

Back on the ship, Lieutenant Loren L. Hickerson, a Langley officer, described the scene in his journal: “The sea grew rougher by the hour—or so it seemed to me. We heard nothing from any of our planes, although ordinarily the strike frequency was full of plane calls. The sea was at its height when the flight returned. We had had rolls up to 24 degrees and when we turned into the wind to recover our planes, the deck was heaving with tremendous swells, like a lifeboat overturned.

“I watched the planes come in from a pilot house porthole, and I have never watched a grimmer nor more startling sight. One after another, our TBF’s came aboard without mishap; how, I will never know. At least half of them had giant holes in the wings or tail or both, from AA fire. I could see from the pilot house that one pilot’s face was covered in blood, and at least two other planes were known to have injured personnel aboard.

“The fighter planes looked OK, except for occasional shrapnel holes in the wings or fuselages, but the torpedo planes showed every sign of having had rough going. One plane’s port wingtip had been staved in, and the fabric was fluttering as he came in. Another plane came in with the flaps blown to pieces. When I went below I learned that Lt. Hal Payne was taken dead from the greenhouse of Dave Marks’ plane. A shell had exploded in his compartment, killing him instantly.

“The next afternoon we buried our dead at sea—for the first time in our lengthening cruise against Japan. A Marine guard stood stiffly at attention, with officers and men in whites and dungarees, on the hangar deck among the TBFs and fighter planes. The band played a dirge as the pallbearers bore the flag-draped bodies to the starboard gangway opening amidships. The Captain and the Chaplain walked down behind them. The service was brief, and simple, and the bodies were dropped silently into the grey waters 600 miles from Tokyo.

“It made me a little sick—the thought of Marks and Winn flying home with those bodies who had been their friends and who had joked with us a few hours before. But there was no deep emotional stir. If there were, none of us, let alone these pilots who fly against the enemy again tomorrow and the next day, would be able to stand it. Today, Hal Payne and Blackie Marsh are forgotten. It can’t be any other way. To remember them would be to shake the very foundations upon which we live out here. To live constantly with, but as constantly to ignore, the grim realities which face men and ships, pilots and planes, in enemy waters—this seems to me one of the greatest oddities of all. None of us is asleep to what could happen. There is no fear. Only the inexperienced know fear.”

“We Have Lost a Good Man From Our Midst”

There is an old saying: “Timing is everything.” If the Japanese gunner had been a hair quicker, or if Dad’s Avenger had been a hair slower, they would have crashed into the volcanic sands of Iwo Jima. End of story. But that did not happen.

Dave Marks retired from the Navy with the rank of commander in 1960 and worked another 20 years for Grumman, the same company that built his Avenger. He had four children. Emil Sellars was burdened with a sense of guilt that he had killed Hal Payne with that shot of morphine. Around the middle of each June he became distant and quiet, spending much time alone in his yard in South Carolina. He died in 1971, leaving behind two children. Vernon Cravero lives in the Chicago area. He has two children and enjoys spoiling his great grandchildren. Their damaged Avenger was judged beyond repair and pushed over the side. Today it rests somewhere on the bottom in the icy blackness of the deep Pacific.

Hal Payne’s obituary in the Dartmouth College Alumni magazine concluded with this tribute from a friend: “He was rugged in both mind and body, and I’m sure he would have gone far in the years to come in this war-torn and war-weary world. As I remember him, he loved life and action—he got it I’m sure—but in so doing we have lost a good man from our midst.”

Thank you for this look into lives of men who put their lives on the line everyday so that we can be here today. Thank you for sharing a brief moment from you dad’s life.

You’re welcome. Glad you enjoyed the article.