By William Stroock

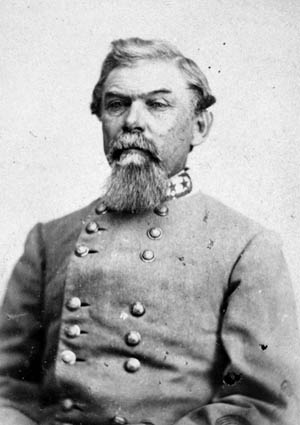

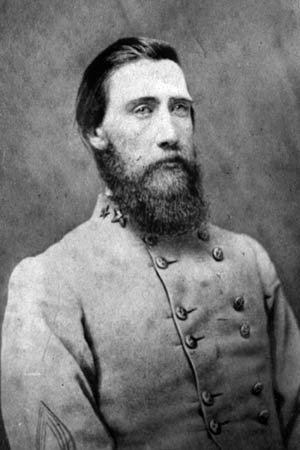

On September 3, 1864, a triumphant Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman telegraphed Washington, “Atlanta is ours and fairly won.” Ironically, Sherman, renowned for his tenacious fighting style, had won the city through ingenuity. Rather than directly assault Atlanta’s fortifications, he had marched south-southwest and fought a campaign of maneuver against Confederate General John Bell Hood. On September 1, when Sherman took the town of Jonesboro, 10 miles south of Atlanta, he cut the city’s last remaining rail link. However strong Atlanta’s defenses may have been, Confederate forces risked another Vicksburg-like catastrophe if they remained in the city. Withdrawal was Hood’s only option.

Sherman now controlled all of northern Georgia. In his postwar memoirs, he set the scene concisely: “By the middle of September, matters and things had settled down in Atlanta, so that we felt perfectly at home. The telegraph and railroads were repaired, and we had uninterrupted communication to the rear. The trains arrived with regularity and dispatch and brought us ample supplies.” Sherman had more than 200,000 troops in his overall command around Atlanta, with slightly more than 80,000 fighting men divided into five corps, four infantry and one cavalry. These were commanded by an unspectacular but competent cadre of generals.

While he had triumphed at Atlanta, Sherman still faced several daunting problems. The first was logistical. He was at the end of a long supply line stretching hundreds of miles north to Chattanooga and beyond to Nashville. It was extremely vulnerable to attack, as Sherman’s Confederate counterpart, John Bell Hood, soon proved. With his army of 35,000 men, Hood began operating in the area of Palmetto on the Chattahoochee River, southwest of Atlanta, and demonstrating against Union garrisons along Sherman’s lines of communication. Hood himself had an excellent line of communication running back to Florence, Alabama, from any part of which he could confront Sherman directly or harry the roads and rail lines in his rear.

Delaying Sherman’s Advance

While Sherman consolidated his strength, Confederate President Jefferson Davis railed against him. With Southern morale collapsing in the face of Sherman’s victory, Davis toured Georgia making grand speeches to a shell-shocked populace. Sherman received reports of speeches in which Davis claimed the Confederate Amy was taking decisive action and boasted that Sherman would soon retreat from Atlanta as Napoleon had from Moscow. “The fate that befell the Army of the French Empire in its retreat from Moscow will be re-acted,” Davis told the people of Macon. Meanwhile, Davis said, Hood and the fearsome cavalry raider Nathan Bedford Forrest would be acting against Sherman’s vulnerable communications and moving into central Tennessee.

This is exactly what Hood did, for two reasons. First, with Confederate morale collapsing, Hood reasoned that a series of short, sharp offensives could only improve the situation. “Something was absolutely demanded,” Hood wrote in his report to Secretary of War Judah Benjamin. Second, Sherman’s forces were so numerically superior to Hood’s that the latter could only take some peripheral action. “Thus I determined upon consultation with the corps commanders to turn the enemy right flank and attempt to destroy his communications and force him to retire from Atlanta.”

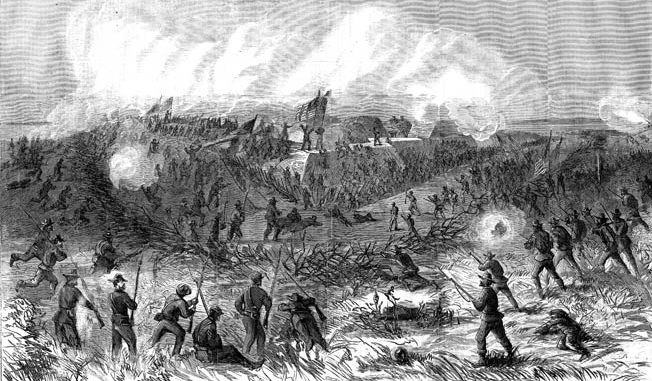

In early October Hood sent a division under Maj. Gen. Samuel G. French against the Union garrison at Allatoona, threatening to massacre the troops there. This ploy had already worked for Forrest, who scared the Union garrison at Athens into surrendering. French sent a letter to the Union commander calling for him to “avoid the needless effusion of blood.” Fortunately for the Union cause, the garrison commander, Brig. Gen. John M. Corse, was made of sterner stuff and replied, “We are prepared for the ‘needless effusion of blood’ whenever it is agreeable to you.” Union troops repelled French’s attack. Corse himself was shot in the face but seemed almost cheerful about his wound. “I am shot a cheek-bone and an ear, but am able to whip all hell yet!’ he wrote Sherman.

On October 12, Hood followed up his Allatoona adventure with a raid on Resaca, where he tried the same ploy. “I demand the immediate and unconditional surrender of the post and garrison under your command,” Hood wrote to the Federal commander, Colonel Clark R. Weaver. “If the place is carried by assault, no prisoners will be taken.” Weaver replied defiantly, “In my opinion I can hold this post. If you want it, come and take it.” Hood, after being bloodied at Allatoona, withdrew of to the west. This was accompanied by a raid on Forrest’s part into central Tennessee. While Forrest damaged roads and chewed up rail lines, Sherman was unconcerned. In reference to Forrest he wrote, “But, as usual, he did his work so hastily and carelessly that our engineers soon repaired the damage.”

While Hood and Forrest were doing little long-term damage to Sherman, their raids were having the desired effect of driving him to distraction and delaying further offensive action. Hood’s attacks forced him to scatter his army along his lines of communication from Atlanta to Chattanooga. Sherman would have liked nothing better than to catch and engage Hood, but in the aftermath of the Allatoona and Resaca raids, Hood showed that he could slip away at will. Sherman was reluctant to give chase, knowing that would wear down his army and open up his lines of communication to further harassment.

“I Can Make This March and Make Georgia Howl!”

Frustrated by the continuing back and forth, Sherman looked for ways to seize the initiative. By October 10, while Hood and Forrest where conducting the Tennessee and Resaca raids, Sherman was toying with a radical idea. He wrote Grant, “It will be a physical impossibility to protect the roads, now that Hood, Forrest, Wheeler, and the whole batch of devils are turned loose.” He argued that rather than stay put in northern Georgia he should cut his communications and march southeast for Savannah. “Until we can repopulate Georgia, it is useless for us to occupy it,” Sherman reasoned, “but the utter destruction of its roads, houses, and people will cripple their military resources.” He concluded famously, “I can make this march and make Georgia howl!”

While the Allatoona raid seems to have made up Sherman’s mind, he had been considering a march out from Atlanta ever since Hood began his harassing operations. “As soon as Hood had shifted across from Lovejoy’s to Palmetto, I saw the move in my ‘mind’s eye,’” he recalled, “and after Jeff. Davis’s speech at Palmetto, of September 26th, I was more positive in my conviction, but was in doubt as to the time and manner.”

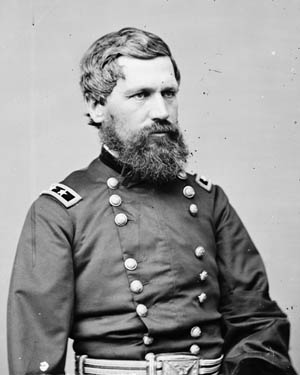

Sherman tested his idea of living off the land. When Hood demonstrated against Dalton on October 13, Sherman severed his supply line and chased Hood down the Chattooga Valley, “drawing our supplies of corn and meat from the farms of that comparatively rich valley and of the neighborhood.” At the same time, Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum, one of Sherman’s unspectacular but competent generals, dispatched a foraging party east from Atlanta. Sherman wrote that Slocum’s foragers had brought back “large trains of wagons to the east, and brought back corn, bacon, and all kinds of provisions, so that Hood’s efforts to cut off our supplies only reacted on his own people.”

These two maneuvers convinced Sherman that his plan for marching through Georgia and living off the land was feasible. “Georgia has a million inhabitants,” he said. “If they can live, we should not starve.” Sherman ordered copies of the 1860 census and examined these to determine his general route through Georgia. In 1860 the state had produced more than 50 million pounds of rice and raised more than two million hogs. Sherman planned a march through the “Black Belt,” a fertile stretch of land running through the north central part of the state. The Black Belt accounted for four-fifths of Georgia’s annual cotton production (726,000 bales in 1860). Plundering the region would be a devastating economic blow. This area was also extremely vulnerable, as African Americans accounted for 55 percent of the population. In the coastal region, slaves made up 59 percent of the population. Georgia’s largest city was Savannah, with more than 22,000 residents. Recently occupied Atlanta was only the state’s fourth largest city with, a population of 9,554. Other important cities were Augusta (12,493) and Columbus (9,631). Macon, with 8,247 people, was the state’s fifth largest city.

Sherman’s grand idea was about more than simply outsmarting Hood. He felt that from Atlanta he could march to the sea and rip out the heart of the Confederacy. The march would create a dead zone that split the Confederacy in two. By marching through Georgia, Sherman felt he could strike a blow to Confederate morale from which the South could not recover. Sherman was greatly amused by Jefferson Davis’s grand proclamations in the aftermath of the Atlanta campaign. “I am convinced the best results will follow from out defeating Jeff. Davis’s cherished plan of making me leave Georgia by maneuvering,” he told Grant. The chance to embarrass the Confederate president was too great to resist.

His correspondence with Grant was the first part of Sherman’s planned campaign to convince Grant and the Lincoln administration in Washington to approve his march to the sea. Grant initially was skeptical. He had his own issues to worry about. In Virginia he was opposite Robert E. Lee at Petersburg, after having fought three battles, losing two of them, and taking 100,000 casualties in the process. Grant’s reputation had never really recovered from this phase of the war. The public was outraged at the heavy effusion of blood. Sherman’s taking of Atlanta in September saved not only Grant but Abraham Lincoln’s flagging reelection campaign.

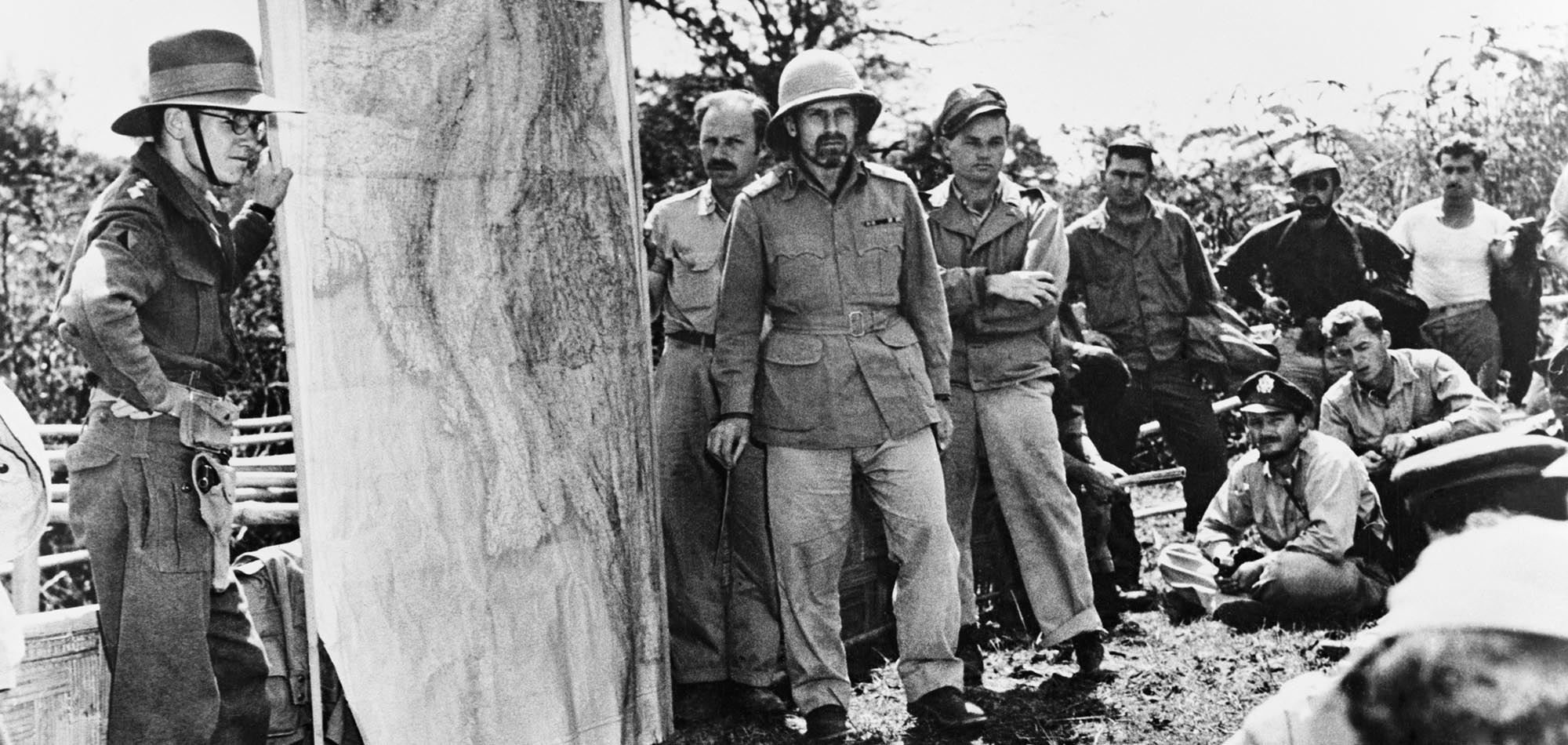

Even as he telegraphed Grant on October 10 with his idea of moving east to the sea, Sherman was already making preparations. He trimmed his army of unnecessary personnel and equipment, sending them back to his base at Chattanooga. Sherman then assigned the department’s chief quartermaster to oversee the repair of rails along the Chattanooga-Atlanta line. To secure the line he dispatched Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas and the IV Corps to garrison the key towns of Nashville, Chattanooga, and Decatur, Georgia.

During this time, Hood remained in a position to harass Sherman’s communications, while Forrest executed a daring river raid in western Tennessee in which he captured or sank several Union supply ships. Sherman telegraphed the full details of Forrest’s raid and Hood’s current position and once again made his case for an expedition to the sea. Grant, never afraid to bring about a major battle, replied that he thought since Hood was easily located in his north, this was the time and place for Sherman to attack and remove Hood’s menace once and for all. “If you can see a chance of destroying Hood’s army, attend to that first, and make your other move secondary,” Grant advised. Sherman replied that he believed he simply couldn’t catch up to Hood, whose army was smaller and leaner. Sherman pointed out that he had “reduced baggage” and was prepared to move in any direction, “but I regard the pursuit of Hood as useless.” Sherman assured Grant that he was prepared to battle Hood if necessary, but as long as he was forced to hold on to Atlanta, “my force will not be equal to this.”

On November 2, Grant finally telegraphed Sherman saying in part, “I do not see that you can withdraw from where you are to follow Hood without giving up all we have gained in territory. I say then, go on as you propose.” A few days later, Sherman sent Grant his formal plan of march. Grant replied on November 7, “I see no reason for changing your plan. Should any arise, you will see it, or if I do I will inform you.”

In a later communication to Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, Sherman articulated his thinking and grand strategy. “I attach more importance to these deep incursions into the enemy’s country,” he wrote. Sherman said that the war in America differed from European warfare in that “we are not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people. And must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war, as well as their organized armies.” He talked of the Georgians’ faith in Davis being shaken and looked forward to doing the same to the people of the Carolinas.

Sherman’s Planned Devastation

While Georgia was the breadbasket of the Confederacy, Sherman understood that the army he took with him through the state must be lean and trim to facilitate fast movement. “The most extraordinary efforts had been made to purge this army of non-combatants and of sick men,” he wrote. He systematically purged the sick, lame, lazy, and generally unnecessary men from his force around Atlanta, reducing his numbers from about 81,000 men to just over 60,000. He took a rapier to the artillery train as well, reducing the compliment to 65 guns and 200 shells for each, and slashing the wagon complement so that each of his four columns was reduced to a mere 800 wagons, enough for foraging and a rolling supply train, but no more. Drawn by a team of four horses, each wagon could haul about 2,500 pounds.

Sherman took along a 20-day supply of rations, beef on the hoof, and five days of forage for the horses and cattle. Each man carried a musket, 40 rounds of ammunition, a tin cup, and a haversack. Theodore Upson, a private with the 100th Indiana, described the trimmed-down accoutrements carried by the rank and file on the march: “All a good many carry is a blanket made into a roll with their rubber ‘poncho’ which is doubled around and tied at the ends and hung over the left shoulder,” said Upson. “Of course, we have our haversacks and canteens, and our guns and cartridge boxes with 40 rounds of ammunition. Some of the boys carry 20 more in their pockets.”

Sherman organized his army into two wings. The right, commanded by Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard, 34, and the left commanded by Slocum, 37. Both generals held Sherman’s full confidence. Sherman described his wing commanders as “both comparatively young men, but educated and experienced officers.” Howard had XV and XVII Corps, totaling seven divisions, while Slocum commanded XIV and XX Corps, totaling six divisions. Each corps would march more or less independently of each other and Sherman. Each corps had with it a swinging pontoon bridge, 900 feet long. Sherman held Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick’s cavalry division in reserve and would use it over the course of the campaign to keep Confederate cavalry and skirmishers at bay.

Sherman chose his path well, relying on the intricate series of roads in Georgia to facilitate the movement of each corps. The corps would march in unison but function as semi-independent forces with their own self-contained supply train. That supply train would be augmented by Sherman’s foraging scheme whereby skirmisher parties, the soon-to-be infamous “bummers,” would scout ahead. Each brigade assembled a foraging force of men and wagons under the command of a picked officer to supervise the effort. The columns were to avoid picking up stragglers and refugees at all costs, although able-bodied freedmen could be co-opted and organized into pioneer battalions.

Sherman took steps to limit the destruction wrought on private property. His Special Field Order No. 20 read in part: “To Corps commanders alone is entrusted the power to destroy mills, houses, cotton-gins, etc. In districts and neighborhoods where the army is unmolested, no destruction of such property should be permitted.” Sherman did make exceptions for certain individuals. On November 20, Sherman was riding with XX Corps when it encountered the plantation owned by Confederate General Howell Cobb, commander of Cobb’s Legion and former secretary of the treasury in the Buchanan administration. Sherman sent a message back to the local division commander, Jefferson C. Davis, instructing him to “spare nothing.” This was part of Sherman’s overall policy of harsh measures to those who fought back. When the army encountered resistance in the form of guerrillas or bushwhackers, or if the locals destroyed infrastructure prior to the army’s arrival, Sherman mandated that “commanders should order and enforce a devastation more or less relentless.”

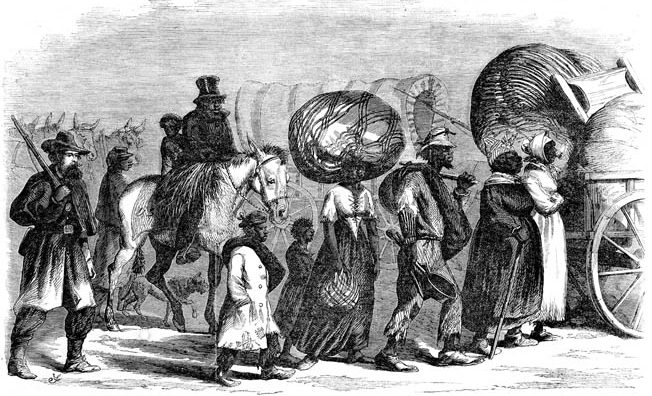

There was also the issue of what to do with Georgia’s slaves. Nearly 446,000 African Americans lived in Georgia, the overwhelming majority of them (all but 0.03 percent) slaves. Sherman, frankly, wanted nothing to do with them. The slaves, however, were very interested in Sherman, which became evident as early as the army’s arrival in Covington. Upon entering the town, Sherman found “the negroes were simply frantic with joy. Whenever they heard my name, they clustered about my horse, shouted and prayed in their particular style.” Sherman became a messianic figure to the new freedmen. Even Sherman was moved by the outpouring of joy, although he did not welcome it. Outside of Covington he met with a group of freedman and told them in no uncertain terms that “we wanted the slaves to remain where they were, and not load us down with useless mouths.”

Indiana Private Upson encountered slaves on a personal level and found that “despite all discouragements we have a large following though General Sherman has tried in every way to explain to them that we do not want them.” Upson wrote of freedman ecstatic with joy at the mere rumor of Sherman’s riding nearby and described a group of freedman mistaking a grizzled bummer for the general and “marched along the side of the road singing their songs till someone told them the truth.”

Atlanta “Smoldering and in Ruins”

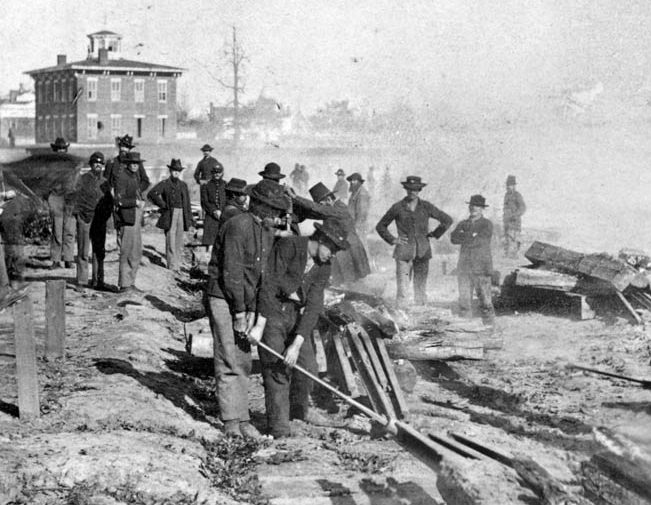

As the army departed Atlanta, the military facilities in and around the city were systematically demolished. Sherman put his chief engineer, Colonel Orlando M. Poe, in charge of the destruction. Poe destroyed utterly the facilities of the Georgia Railroad, including a machine shop that the Confederates had been using as a artillery depot. The resulting explosion caused a considerable conflagration. “The fire also reached the block of stores and the depot, and the heart of the city was in flames all night,” claimed Sherman.

Sherman was not maintaining communication with his northern Georgia base, but he did go to great efforts to ensure it was secure against Hood’s army. He left General Thomas in Nashville with two corps, a cavalry brigade, and a third corps en route from Missouri. He expected the Confederates to strike. Thomas had one division at Decatur, one at Murfreesboro, and one at Chattanooga, all linked by a rail patrolled rail line. Thomas, for his part, was supremely confident. “I have no fears that [General P.G.T.] Beauregard can do us any harm now,” he told Sherman, “and, if he attempts to follow you, I will follow him as far as possible.”

On November 16, Sherman’s army of 62,000 men set out. Behind them, Atlanta was “smoldering and in ruins,” wrote Sherman unapologetically, “the black smoke rising high in the air, and hanging like a pall over the ruined city. Away off in the distance, on the McDonough road, was the rear of Howard’s column, the gun-barrels glistening in the sun, the white-topped wagons stretching away to the south; and right before us the Fourteenth Corps, marching steadily and rapidly, with a cheery look and swinging pace, that made light of the thousand miles that lay between us and Richmond.”

The men, too, were in high spirits as they set out on a great unknown adventure. They sang verse after verse of “John Brown’s Body,” and Sherman reported that “never before or since have I heard the chorus of ‘Glory, glory, hallelujah!’ done with more spirit, or in better harmony of time and place.” Most thought they were destined for Richmond, not the sea. Sherman had no fixed point in mind. “Savannah was most desirable,” he thought, “but I kept in mind Port Royal, South Carolina, and Pensacola, Florida, as alternatives.” His only fixed object was the Atlantic Ocean.

During the first phase of the march, Sherman travelled with XIV Corps in Howard’s wing, making Lithonia on the first night. In keeping with his streamlined approach, Sherman’s personal headquarters consisted of one sparsely furnished wagon—all frills of command had been ruthlessly eliminated to set a an example for the other officers. Sherman described vividly the initial acts of destruction on the march. “The whole horizon was lurid with the bonfires of rail-ties,” he wrote, “and groups of men all night were carrying the heated rails to the nearest trees, and bending them around the trunks.” Sherman thought the destruction of the railway particularly important and liked to personally oversee the effort. XIV Corps camped at Covington the second day out with Union troops marching to band music with colors unfurled. Recalled Sherman, “The white people came out of their houses to behold the sight, in spite of their deep hatred of the invaders.” The slaves, biding their time, kept mostly to themselves.

On the left, XX Corps entered Madison, which lay on the rail line linking Augusta with Atlanta. This movement by Slocum’s wing conveyed the false impression that Sherman’s next target was Augusta, indicating that Sherman was marching to link up with Grant in Virginia. On the right, Howard’s wing was moving more or less in a straight line toward Macon. After taking Macon he could pivot left toward Milledgeville to cover the move to Augusta. But rather than move on Augusta, XIV Corps pivoted right toward Milledgeville, then the capital of Georgia.

For the next week the army marched without incident, encountering no organized resistance whatsoever. Slocum’s left wing converged on Milledgeville, entering the state capital on November 23—exactly one year after Sherman’s less than stellar performance at Missionary Ridge overlooking Chattanooga. Southern civilians were easier to overawe than Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne’s veterans had been at Missionary Ridge. ‘The first stage of our journey was, therefore, complete, and absolutely successful,” said Sherman.

After destroying all military facilities and convening at the capital, a mock assembly was held to repeal Georgia’s orders of secession and rejoin the Union. The left wing marched out of Milledgeville on November 24. “I was not present at these frolics,” Sherman wrote “but heard of them at the time and enjoyed the joke.”

The Capture of Savanna

While Sherman was at Milledgeville, Confederate Lt. Gen. William Hardee, one of the Georgia governor’s advisers, scraped together 3,000 poorly trained state militia and attacked Howard’s rear guard at Griswoldville, on the Central Georgia Railroad nine miles north of Macon. Howard’s veterans were well positioned on a hill with their flanks protected by swampland and a clear line of fire over breastworks to the front. The Georgia militia made three charges, each one easily devastated by the skilled Union infantry, before retreating to Macon and leaving 600 casualties on the field. Union losses were one-tenth that number. Upon examining their victims, the Federal troops saw with a mixture of sorrow and regret that the attackers had consisted almost entirely of old men and boys.

At Milledgeville, an even more horrible sight confronted the Federals. While they were celebrating Thanksgiving Day with a feast, their meal was interrupted by the arrival of several escaped prisoners from the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville, which lay 80 miles to the southwest. The sight of the walking skeletons aroused rage and bitterness in Sherman’s men, who were furious that their comrades had been allowed to slowly die from starvation in the midst of what was clearly rich farmland. The sight hardened the Federals’ hearts and made their destructive work that much easier to commit. Once again, Sherman committed his wishes to paper, issuing standard orders for his bummers “to forage liberally on the country. To this end, each brigade commander will organize a good and sufficient foraging party, under the command of one or more discreet officers, who will gather, near the route traveled, corn or forage of any kind, meat of any kind, vegetables, corn-meal, or whatever is needed by the command, aiming at all times to keep in the wagons at least ten days’ provisions for his command, and three days’ forage.”

Both the left and right wings tacked nearly due east, Slocum’s left aiming for Millen, Howard’s right for Louisville. By this maneuver Sherman once again used Augusta as a foil to fool the Confederates. East of Louisville lay Waynesboro, with a direct rail link to Augusta. While the march maintained its standard 15 miles per day, Sherman this time faced organized resistance in the form of Joseph Wheeler and his 3,000 cavalry. To counter Wheeler, Sherman transferred Kilpatrick’s cavalry from the right to the left wing. Wheeler daily harassed Howard’s wing, skirmishing constantly with Kilpatrick’s cavalry. Kilpatrick gradually pushed Wheeler back through Waynesboro by December 2. The next day Sherman marched into Millen with XVII Corps. Slocum and XX Corps were four miles north and XIV Corps was a further 10 miles north demonstrating against Augusta. This completed the second leg of Sherman’s journey. He was two-thirds of the way to Savannah.

Sherman now pivoted left, heading straight for the Georgia coast. There could be little doubt now that Savannah was his ultimate target. Within the city General Hardee, whom Sherman called “a competent soldier,” rallied the populace and dug an intricate series of earthworks to defend against attack. The corps converged on Savannah, arriving at its outskirts on December 9 and 10. Having avoided a frontal assault on Atlanta, Sherman had no intention of launching one on Savannah. He did detach one division to take Fort McAllister, on Ossabaw Sound, which was preventing him from linking up with naval vessels lying offshore with new supplies for the Federal troops. The fort was taken by direct assault, under Sherman’s eye, by Sherman’s old 2nd Division, which he had commanded at Shiloh. Watching alongside Howard from the roof a nearby rice mill, Sherman exulted, “They’re on the parapet! They took it, Howard. I’ve got Savannah!”

Sherman made contact with the fleet, boarded the steamer Dandelion, and sent a brief message to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, the first anyone in the North had heard from Sherman in a month. Sherman still had the ultimate capture of Savannah to think about. On December 17 he sent a letter to Hardee demanding the city’s capitulation. In his exhortation Sherman intentionally mimicked Hood at Allatoona and Resaca, offering liberal terms but also threatening, “Should I be forced to resort to assault, or the slower and surer process of starvation, I shall then feel justified in resorting to the harshest measures, and shall make little effort to restrain my army.” Hardee was unimpressed and vowed defiance. Sherman reluctantly made plans to take Savannah by storm and conducted personal reconnaissance of its environs in preparation.

In the end Hardee evacuated the city on the night of December 21, marching north over a pontoon bridge across the Savannah River and wrecking the navy yard before departing. “I was disappointed that Hardee had escaped with his army,” said Sherman, “but on the whole we had reason to be content without the substantial fruits of victory. Entering Savannah, he jotted down, “Here terminated the ‘March to the Sea.’” Behind that bland statement, Sherman and his bummers had done more than $100 million in damages to the State of Georgia and its dazed residents.

Praise and Condemnation For the March to the Sea

The next day Sherman sent an immensely satisfying telegram to President Lincoln. “I beg to present you as a Christmas-gift the city of Savannah.” Relieved and grateful, Lincoln responded, “When you were about to leave Atlanta for the Atlantic coast, I was anxious, if not fearful; but, feeling that you were the better judge, and remembering ‘nothing risked, nothing gained,’ I did not interfere. Now, the undertaking being a success, the honor is all yours; for I believe none of us went further than to acquiesce. It is indeed a great success. Not only does it afford the obvious and immediate military advantage, but, in showing to the world that your army could be divided, putting the stronger part to an important new service, and yet leaving enough to vanquish the old opposing force of the whole, Hood’s army, it brings those who sat in darkness to see a great light.”

The London Times, couching its praise in a comparison its readers could understand, noted of Sherman’s feat, “Since the great Duke of Marlborough turned his back upon the Dutch and plunged hurriedly into Germany to fight the famous battle of Blenheim, military history has recorded no stronger marvel than this mysterious expedition of General Sherman’s route against an unknown undiscoverable enemy.”

Confederate Captain Robert E. Park of the 12th Alabama Infantry privately begged to differ, writing in his diary, “Attila, Genseric and Alaric were not more cruel to the conquered Romans than the brutal Sherman has been to the defenseless, utterly helpless old men, women and children of pillaged and devastated Georgia.” All four leaders, it went without saying, were victorious.

To the end of his life Sherman remained unapologetic. Writing to an old comrade a decade and a half later, he noted, “I never feel disposed to apologize for or excuse anything. Those people made war on us, defied and dared us to come south to their country, where they boasted they would kill us and do all manner of horrible things. We accepted their challenge, and now for them to whine and complain of the natural and necessary results is beneath contempt.”

Sherman was a glorified War Criminal, to say the very least.

“War is cruelty and cannot be refined.”–LTG W.T. Sherman

No, the real criminals are the overseers at Andersonville. Sherman was and is a hero.

War is not a gentleman’s “game”. Maybe if we remembered what a horror it is we wouldn’t have so many idiots clamoring for another civil war now as if there is some kind of “regeneration” function in real life.

Like the general himself said, “I never feel disposed to apologize for or excuse anything. Those people made war on us, defied and dared us to come south to their country, where they boasted they would kill us and do all manner of horrible things. We accepted their challenge, and now for them to whine and complain of the natural and necessary results is beneath contempt.”

A brilliant plan that payed off in every way by limiting casualties in every way.