Thousands of military personnel killed in action during World War II rest in unmarked graves, high on mountaintops, beneath the ocean amid the wreckage of sunken ships, in remote jungles and arid deserts. For 63 years, the remains of Staff Sergeant Martin F. Troy lay unknown and unrecognized near the village of Nemesvita, Hungary, about 110 miles from the nation’s capital city of Budapest.

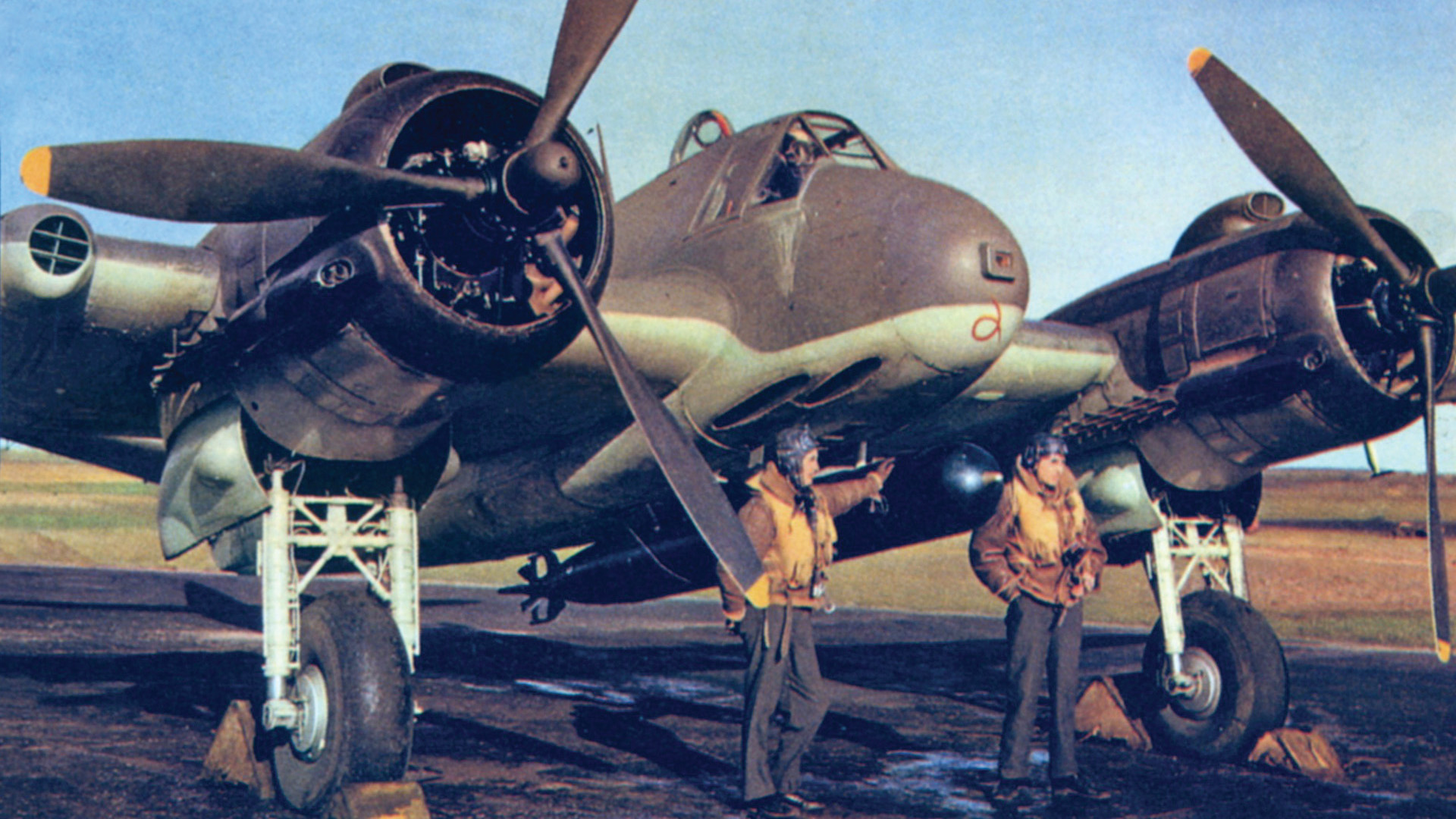

Troy, of Norwalk, Connecticut, was an airman who lost his life on June 30, 1944, while on a mission aboard a Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber nicknamed Miss Fortune. Returning to its base in Italy after a raid over Germany, Miss Fortune was caught in bad weather and then attacked by enemy twin-engine Messerschmitt Me-110 fighters. Troy was the only member of the 10-man crew who remained missing after the crash into marshy land, which left a crater some 18 yards long by six yards wide and covered with up to three feet of water.

Ironically, the crash site was well known to local inhabitants and had been salvaged for scrap metal through the years. Survivors had given accounts of the incident and related that Troy had probably died in a fire aboard the bomber before it hit the ground. One fellow crewman had been severely burned in an effort to rescue him. Still, Troy’s remains went unrecovered. In 1945, according to the Associated Press, the American Graves Registration Unit had determined that the remains could not be repatriated due to the inaccessibility of the crash site and the uncooperative nature of the communist post-war government of Hungary. The airman’s official status was listed as “killed in action, body not recovered.”

In July of last year, a recovery team from the U.S. Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), based in Hawaii, made the trek to Hungary as a renewed effort to locate Troy’s remains was fueled by what a JPAC spokesman termed “congressional interest.” While all the surviving members of Miss Fortune’s crew are now deceased, they had apparently lobbied for the successful expedition. Human bones were found scattered around the site of the crash, and DNA testing is expected to confirm that they belong to Sergeant Troy. Once the identity is confirmed, an attempt will be made to locate family members, and at long last the airman will receive a proper burial.

JPAC is responsible for the recovery and identification of American service personnel killed in action, and its task is daunting. Presently, a mere five teams such as the one dispatched to Hungary are available to locate and recover the remains of an estimated 80,000 Americans who are still missing from World War II. Lt. Gen. Jozset Hollo, the director of a military museum in Hungary, has informed JPAC that information is available on at least 30 more Americans who perished in Hungary during the war.

In this issue, WWII History marks the passing of friend and colleague Charles Whiting. Born in 1926, Charles joined the British Army at the age of 16 and served during World War II with the 52nd (Lowland) Divisional Reconnaissance Regiment following the D-Day invasion. He went on to become one of the most prolific authors of historical fiction and nonfiction in the world, writing with a verve and excitement that conveyed his true passion for the craft. Charles was a frequent contributor to WWII History and leaves a legacy of more than 200 books and a multitude of articles written during a career that spanned more than half a century.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments