By Audrey Lemick

When most people think of the U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II, the first image that usually comes to mind is that of the heavy bombers, the B-17s and B-24s, that ravaged targets in Europe and the B-29s that wreaked havoc on Japanese cities in the Pacific.

Second comes recognition of the fighter squadrons that dueled with enemy pilots to protect the aerial fleets of bombers or strafe targets on the ground—trains, truck convoys, and enemy positions.

Hardly any thought these days is given to the brave pilots who risked their lives taking aerial photographs so that the bombers could find their targets and later assess the effectiveness (or lack thereof) of the bombing.

Photo reconnaissance was a vital part of the Allied war effort, and the 30th Squadron, 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group of Lt. Gen. Lewis Brereton’s England-based U.S. Ninth Air Force played a key role in aerial photo mapping, target selection, and documenting enemy troop concentrations and fortifications.

The squadron’s mission was to take still- and motion-picture films of enemy positions, bomb-damage assessment photos following bombing raids, and included, as a 1943 Air Force booklet pointed out, “securing information necessary for planning the employment of a striking force.” The 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Group was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for its most storied job of flying missions “at minimum altitudes along the Normandy invasion beaches immediately preceding Allied landings [on June 6, 1944].”

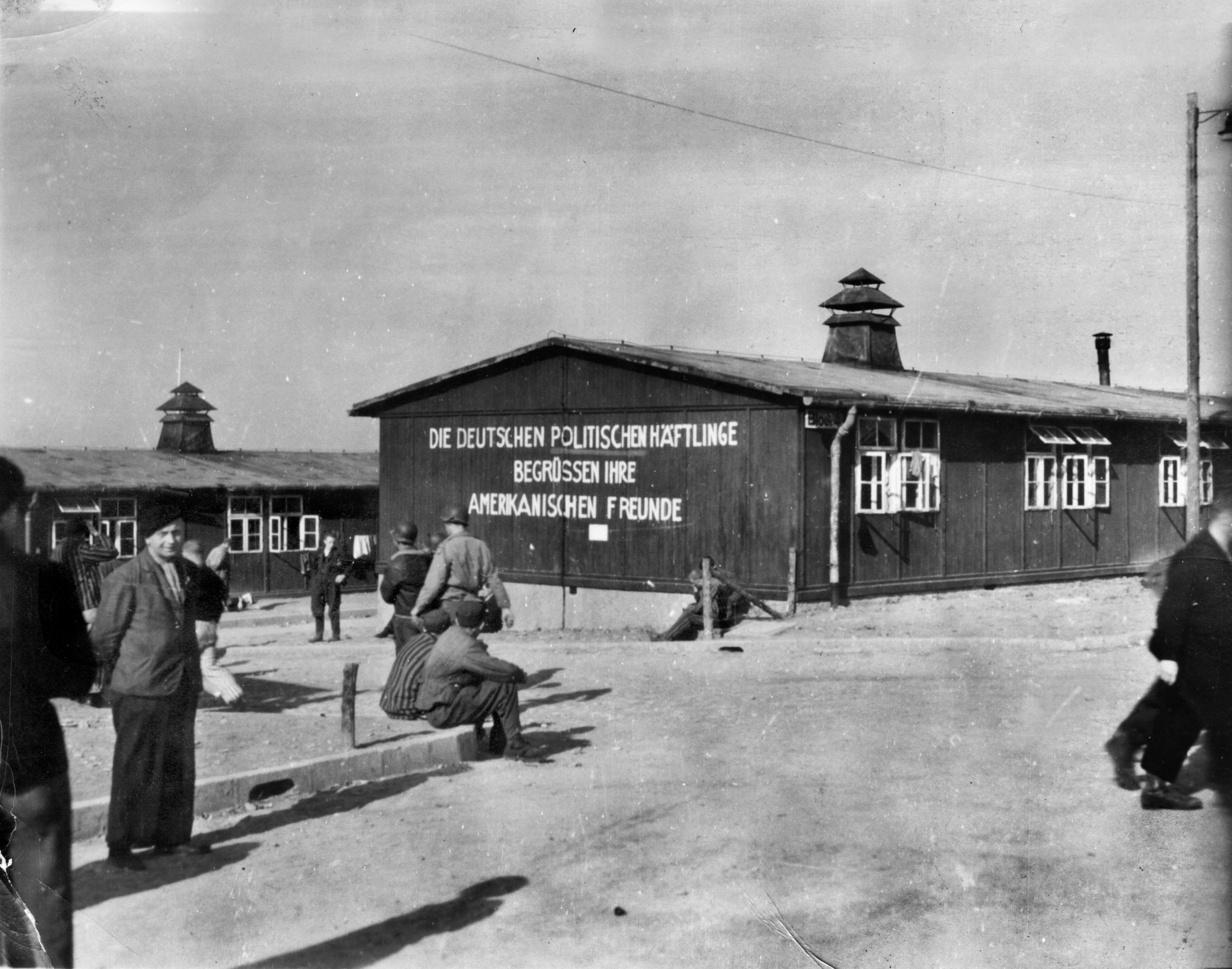

Eventually, the group’s converted P-38 (F-5) Lightning and P-51 Mustang (F-6) camera planes flew more than 5,000 missions, took over 2,200,000 photographs, operated over France, Belgium, and Germany, and were the first American planes to operate from bases east of the Rhine River. At war’s end, members of the squadron became witnesses to Nazi atrocities at the Buchenwald concentration camp outside Weimar, Germany.

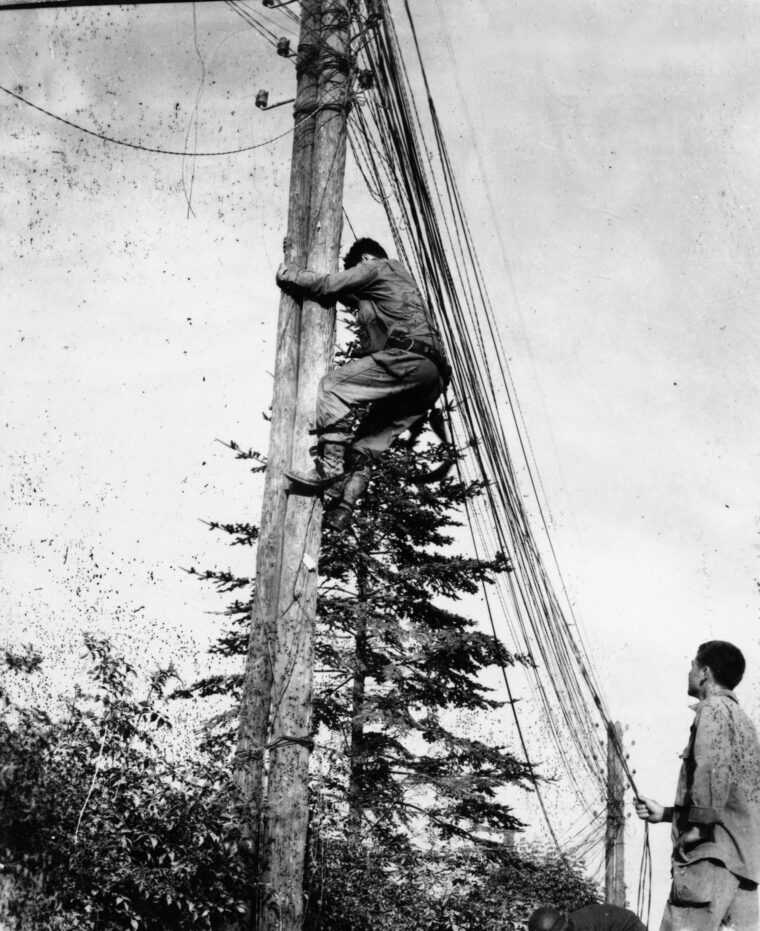

Sergeant Charles D. Lemick of Gary, Indiana, an instrument repair specialist who performed maintenance on instruments carried by unarmed P-38 camera planes, served with the squadron. An avid amateur photographer, Lemick recorded his wartime journeys through England, France, Belgium, and Germany. Although orders were issued prohibiting GIs from taking pictures in combat zones, that order was, luckily for historians, widely ignored. The result is a remarkably candid view of the war by amateur photographers.

These photos were graciously provided by Lemick’s widow, Audrey, of Highlands Ranch, Colorado.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments