By Nathan N. Prefer

On maps of the Pacific, it’s barely visible––a mere, seemingly insignificant speck in a vast ocean. Its name––unlike Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Iwo Jima, Okinawa––is virtually unknown today. Yet, in the autumn of 1944, Angaur Island became another hard-fought piece of real estate in a war that propelled so many previously unknown pieces of real estate into places of strategic importance until they quickly faded from the public’s consciousness.

Angaur is located about 10 miles southwest of Peleliu. It is a small (three miles by six miles) volcanic island with a very small indigenous population who lived by farming, fishing, and phosphate mining. First occupied by the Spanish in the 17th century, it had been sold to Germany after the Spanish-American War and then held under a League of Nations mandate by Japan until 1935, when Japan left the League. From that time on, Japan had exercised virtual sovereignty over the islands.

One of the least known yet most controversial campaigns of the Pacific War was the Palau Islands campaign (Operation Stalemate) in the fall of 1944. Most accounts of that campaign focus on the bloody battle for the island of Peleliu during the campaign, where the veteran 1st Marine Division was decimated while eliminating enemy forces on that island.

The battle fought for nearby Angaur Island, which took place at the same time as the battle for Peleliu, is far less controversial and even less well known, but no less savage. Unlike the Marines, the troops that took Angaur are even less well known than the battles they fought. They were the “Wildcats,” the U.S. Army’s 81st Infantry Division.

Strategically, by midsummer 1944, General Douglas MacArthur’s forces in the Southwest Pacific Theater had conquered all that was necessary for Allied use in New Guinea. During that same summer it had been determined that the next major objective would be the Philippines. The Allies would cut off Japanese lines of supply and communication while at the same time establishing staging areas for the eventual assault on the Japanese homeland.

In the Central Pacific, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Pacific Ocean Areas Theater had just seized the Mariana Islands. Nimitz’s forces, too, were to head farther west to place themselves within striking range of the Japanese home islands.

As reports began to come in about the increasing weakness of advance Japanese positions blocking his way to the Philippines, MacArthur altered his plans. On the advice of Vice Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, he decided to abandon several preliminaries and advance directly on the Philippines, thereby speeding up Allied progress across the Pacific.

Nimitz was planning to seize Yap and Ulithi Islands to secure naval bases and airfields to neutralize Japanese positions in the Caroline Islands, particularly the strong Japanese naval base at Truk Island. Once that operation was completed, Nimitz’s forces were to seize the entire Palau Island group to advance farther west while at the same time protecting the flank of MacArthur’s advance toward the Philippines.

But here, too, new information changed the early plans. News of heavy Japanese reinforcements being rushed to the Palau Islands, and his own shortage of troops, equipment, and shipping resources changed Nimitz’s mind as well. Instead of seizing the entire Palau Island group, he altered his plans to seize the three largest islands in the southern section of that group: Angaur, Ngesebus, and Peleliu. This would provide the necessary airfields and anchorages required for future operations while conserving scarce resources. But even these supposedly “final” plans were soon to be altered once again as new intelligence arrived and was digested by the two commanders.

When all the planning was done, the seizure of Yap and the Talaud Islands were dropped from the schedule—they would be neutralized by naval and air attacks—while the attacks on Morotai and the Palau Islands would proceed as scheduled; forces were shifted and adjusted to allow for these changes.

For the Palau Islands operation, the overall commander was Vice Admiral Bull Halsey as the Commander, Western Pacific Task Force, and Commander, Third U. S. Fleet. His mission was to seize Ulithi and the southern Palaus. In turn he organized his forces into two groups: the Covering Forces and Special Groups (Task Force 30) under his direct command, and the Joint Expeditionary Force and III Amphibious Force (Task Force 31), both under the command of Rear Admiral Theodore S. Wilkinson.

The Western and Eastern Attack Forces, under Wilkinson, were assigned the task of securing the Southern Palaus and Yap-Ulithi, respectively. The Western Attack Force, under the command of Rear Admiral George H. Fort, was assigned the seizure of Peleliu and Angaur. In turn, Admiral Fort delegated the overall conduct of the Angaur invasion to Rear Admiral William H.P. Blandy.

For the Palaus, the ground force commander was Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger, USMC, who had a wealth of experience in ground and air combat. His command, known as the Western Landing Force and Troops, or as the III Amphibious Corps, USMC, included the 1st Marine Division (Maj. Gen. William H. Rupertus, USMC) and the Army’s 81st Infantry Division, under Maj. Gen. Paul J. Mueller. The 1st Marine Division would assault Peleliu while the 81st Infantry Division would seize Angaur and then be in reserve to assist the Marines on Peleliu. In distant reserve were the 5th Marine Division and the 77th Infantry Division.

The 81st Division had first been organized for World War I where it saw action in the Meuse-Argonne and Alsace-Lorraine offensives. After the armistice, the 81st spent months on occupation duties until returning to the United States and demobilization in June 1919. One distinction the division achieved was creating and issuing the first shoulder patch or shoulder sleeve insignia to its troops, beginning a tradition within the U.S. Army that continues today. From that insignia––a black cat in a green circle––the division got its nickname, the “Wildcats.”

The division lay dormant between the wars, but after Pearl Harbor it came alive again. On June 15, 1942, the 81st Division was reactivated at Camp Rucker, Alabama, and soon redesignated as the 81st Infantry Division. It participated in the Tennessee Maneuvers in 1943, after which it underwent desert training in California. At the end of 1943 it underwent amphibious training at Camp San Luis Obispo, California. With training completed, the division sailed to Hawaii from San Francisco in July 1944.

After a month’s training in Hawaii, the division moved to Guadalcanal where the men conducted final rehearsals at the end of August 1944 in preparation for their first combat assignment. The next month they were aboard troop transports and sailing west toward the Palaus.

The 81st Infantry Division was one of the few wartime divisions that kept the same commander throughout its combat career. That commander was Maj. Gen. Paul J. Mueller. He was born on November 16, 1892, in Union, Missouri, and was commissioned into the infantry from West Point in 1915. During World War I he rose to command a battalion of the 64th Infantry Regiment, 7th Division, in the American Expeditionary Forces. He spent the years 1920-1922 on occupation duty in Coblenz, Germany, before returning to the United States and graduating from the Command and General Staff School in 1923 and the Army War College in 1928. He served with the War Plans Division of the War Department General Staff between 1931-1934 before instructing at the Command and General Staff School from 1935-1940. Then he moved to the position of Chief of the Training Division, Office of the Chief of Infantry, before becoming the Chief of Staff of Second U. S. Army in 1941. He was promoted to brigadier general in October 1941 and got his second star in September 1942. At this time he assumed command of the new 81st Infantry Division and led it into the Western Pacific.

Initially, Japan’s main interest in the Palau Islands was their bauxite and phosphate deposits and, by 1941, some 16,000 Japanese had been sent to the islands for colonization. Japanese strip mining of Angaur’s phosphate deposits—a key ingredient in the manufacture of explosives—had created two small lakes in the north and north-central regions of the island that would soon figure in the American attack.

The Japanese had also constructed a 6,600-foot-long airstrip on the eastern side and narrow-gauge railroad lines that ran through thick underbrush to connect the various mining sites. Although there were more than 6,000 natives in the island group, fewer than 300 resided on Angaur.

The Japanese had a formidable force defending the Palaus, but most of these troops were based on the group’s largest island, Babelthuap. Lt. Gen. Sadae Inoue commanded the Palau Sector Group, a force made up largely of his own 14th Division. Inoue planned to defend his islands at the beaches but, as a man who learned from previous experience, he noted that the “defense-at-the-water’s-edge” tactic had consistently failed at Japanese-held islands to the east. So he modified his plans to include a defense in depth should his beach defenses be breached.

Positions including mines and antiboat obstacles were placed at likely landing beaches on all the Palau Islands, and each island commander was also advised to prepare inland defenses as well. In particular, Peleliu and Angaur were able to take advantage of steep and deep ridge lines in their respective interiors.

Originally, the Angaur garrison consisted of the 59th Infantry Regiment, supported by engineers and artillery. But, for some unrecorded reason, Inoue in July 1944 decided to withdraw the bulk of that regiment to Babelthuap, leaving only the regiment’s 1st Battalion, reinforced with support troops, to defend Angaur.

Under the command of Major Ushio Goto, this force, which included artillery, engineers, antiaircraft and antitank guns, mortars, and service troops, became known as the Angaur Sector Unit; it numbered about 1,400 men. The 59th Infantry Regiment, like its parent unit, the 14th Infantry Division, had been organized in 1905 and was reorganized in 1941. It was an experienced combat unit that had served in Japan, North China, and China before being transferred to the Palaus.

While the 81st Infantry Division trained in Hawaii, General Mueller began to plan his attack on Angaur. His first responsibility was to provide troops to conduct a feint landing at Peleliu, after which he was to land on Angaur. He would be allocated two of his three regiments for the operation, the third regiment being held in reserve for Peleliu should that operation turn out to be more difficult than expected. Then, in mid-September, Mueller, already in transit to the Palaus, was advised that he was to provide one regimental combat team to seize either Yap or Ulithi. That regiment, the III Amphibious Corps reserve, was then designated to seize these islands if it became necessary or desirable.

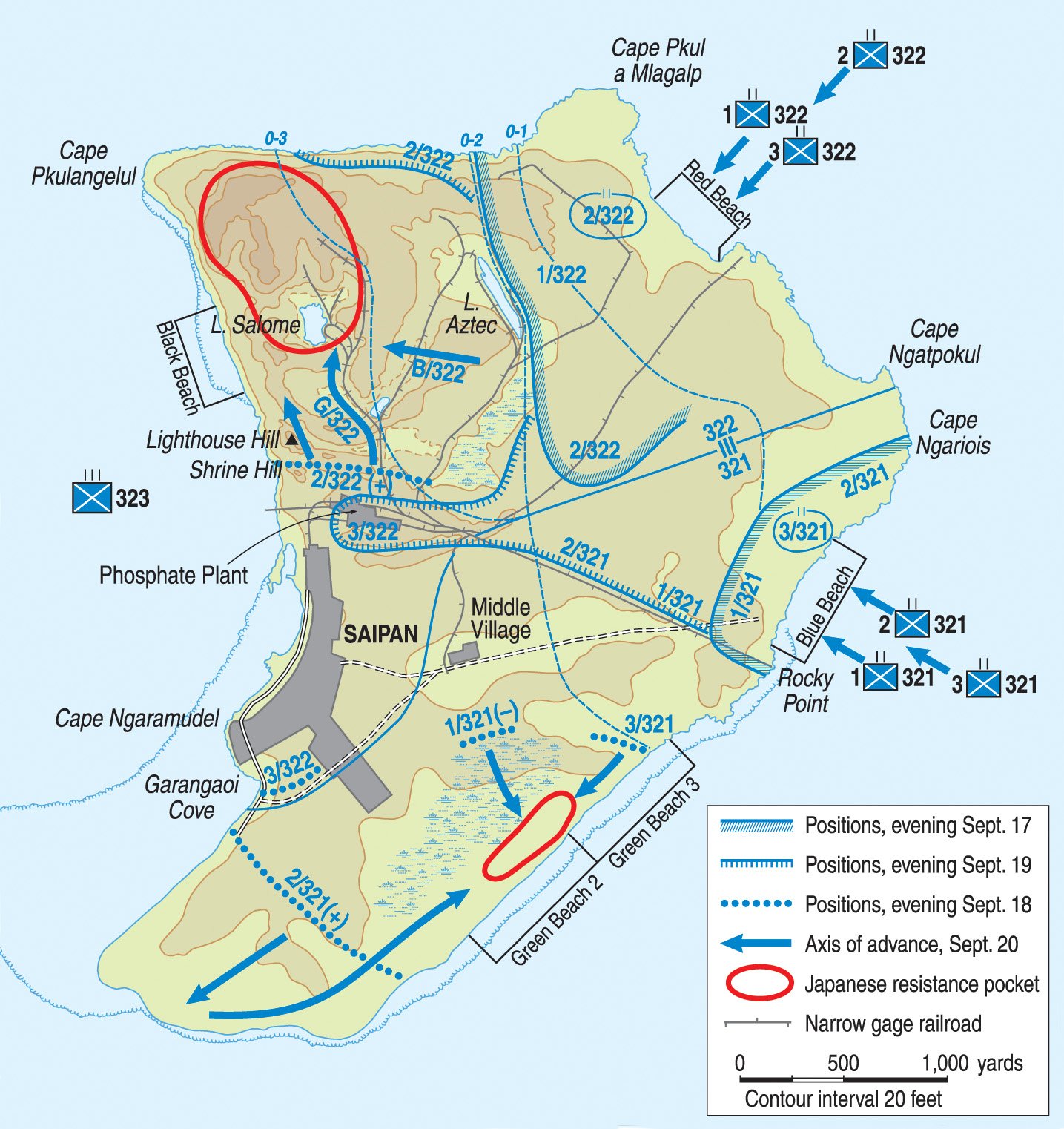

The 81st was to invade Angaur beginning on “F” Day, to distinguish it from other assaults. The 322nd Regimental Combat Team was scheduled to land on Red Beach and the 321st RCT was to land at Blue Beach at 8:30 am. The two assault beaches were separated by 2,000 yards of rough coast and the eastern turn of the island. Mueller knew that this was not ideal, but the difficult terrain of Angaur and known placement of Japanese defenses made his choice inevitable.

Division reserve for the landings was the 3rd Battalion, 321st RCT, which was available to land on either beach should it become necessary. The III Amphibious Corps reserve, the division’s own 323rd RCT, was to feint at another beach to confuse the Japanese.

Division artillery faced a difficult problem, since the narrow island would force the gunners to fire on targets below the minimum effective support ranges. To lengthen the range, Mueller and his artillery commander, Brig. Gen. Rex W. Beasley, would land the supporting artillery on opposite beaches to those regiments they would be supporting. The 105mm guns supporting the 322nd Infantry would land on Blue Beach and those supporting the 321st Infantry on Red Beach. The heavier 155mm guns of the 318th Field Artillery Battalion would come ashore on F+1.

Early on the morning of September 17, 1944, the U.S. Navy’s fire-support ships moved into position off Angaur. Using a slow, methodical area fire, they bombarded the island until supporting aircraft, arriving late, appeared over the island. Dawn brought unlimited visibility, light wind, and a light surf. The infantrymen had no trouble debarking from their transports and into the assault landing craft.

Moving behind rocket and mortar boats shelling the landing beaches, the first wave of Colonel Robert F. Dark’s 321st Infantry landed on Blue Beach on Angaur’s eastern shore at 8:31 am, one minute behind schedule. Only a few rounds of mortar and small-arms fire had opposed the landing. The amphibian tanks quickly moved off to protect the flanks of the incoming assault tractors known as Alligators. Green-clad figures raced from the landing craft and immediately disappeared into the thick jungle underbrush inland from the beach. The Alligators moved back into the water and loaded up with another wave of assault troops.

Offshore, a portion of the 323rd RCT made its feint at Green Beach. As the assault boats came within small-arms range of the beach, they turned and returned their troops to the transports.

Meanwhile, at Red Beach, Colonel Benjamin W. Venable’s 322nd RCT came ashore six minutes late against light resistance. Lt. Col. Leonard L. Cutshall’s 3rd Battalion was slowed by light enemy artillery fire and the need to hack its way through a maze of thick jungle growth behind the beach. The 1st Battalion, under Major William R. White, had no such difficulty and moved quickly inland.

Over at Blue Beach, the two assault battalions of the 321st RCT also slowed due to a maze of debris, barbed-wire entanglements, and enemy land mines. Active Japanese resistance, however, remained slight.

Back at the beach, follow-up waves continued to come ashore. Blue Beach had to be closed for a while until engineers cleared underwater obstacles blocking access. Red Beach continued to receive enemy machine-gun fire for several hours after the first landings. But none of this stopped the buildup.

Lieutenant Colonel Eugene F. Melaville brought his 306th Medical Battalion ashore and was set up for business within hours of the initial assault. The 1138th Engineer Group also arrived and immediately the threatening congestion at the beaches began to disappear and controlled organization took its place. Regimental command posts went ashore and were operating before 3 pm.

The two assault regiments had two immediate objectives: to reach the first objective line or 0-1 line and to make contact with each other and organize a united front line before the Japanese could take advantage of the gap between the regiments. But increasing enemy resistance and the nearly impenetrable jungle in many areas slowed the advance.

The 710th Tank Battalion rolled ashore and came forward to assist in the advance but, so difficult was the terrain, bulldozers had to lead the tanks forward. These difficulties kept the advance limited to a few hundred yards inland.

One of those bulldozers was manned by T/5 Vernon H. Waters of Company A, 306th Engineer (Combat) Battalion, the division’s engineers. Despite enemy fire directed at him personally, he used his machine’s blade to scrape an exit from the beach and then led the advancing infantry, opening trails as he went and removing any obstacles encountered along the way. Individual bravery by the untested American troops was common on Angaur.

Staff Sergeant Leslie L. McKnight of Company I, 322nd Infantry went alone against an enemy cave position, crawling forward until he was close enough to toss grenades into the opening. Pfc. Roy M. Swank of Company L did the same and knocked out an enemy machine gun holding up the advance of his company; he was later killed on Angaur.

First Lieutenant Hugh A. McCandless and S/Sgt. Jesse V. McCoy were forward observers for Battery A, 317th Field Artillery Battalion, advancing with the infantry. Instead of directing the fire of their guns, however, they exposed themselves to enemy bullets and shells to direct the fire of the tanks against enemy fortifications.

Staff Sergeant Henry M. Myers of Company B, 306th Engineers crawled the length of his platoon’s frontline position, knocking out enemy positions as he went. When faced with pillboxes his grenades could not destroy, he stood up to direct the fire of a tank against the pillboxes, and even after being seriously wounded continued to do so until enemy fire ceased. He survived to wear his Distinguished Service Cross.

Although concerned that the dangerous gap between his assault regiments would continue to remain open, General Mueller decided to take the risk and ordered his 322nd RCT, which seemed to have made better progress than the beleaguered 321st, to move forward to the O-2 Line. The 321st Infantry, slowed by terrain and strong enemy defenses in the vicinity of Rocky Point, would catch up as best it could. Meanwhile, the 322nd would advance and close the gap between the regiments.

At Rocky Point, specially trained assault squads took on the prepared enemy defenses. Using the coordination they had learned in training, the demolition squads first placed small-arms fire on the pillbox. Under the cover of this fire the automatic weapons moved up and blazed away at the enemy’s firing ports. Then a flamethrower operator crawled forward to within point-blank range and let loose a burst of flame.

While the enemy reeled from that blast, engineers raced forward and placed demolition charges at vulnerable points on the pillbox. The assault squad then withdrew to a safe distance and awaited the blast. Once the smoke cleared, the squad leader determined if the pillbox was destroyed or needed another “treatment.”

The supporting artillery was by now coming ashore. Lt. Col. John E. Barlow brought his 906th Field Artillery Battalion ashore that afternoon and was open for business by 4:10 pm, but Lt. Col. Carl Darnell’s 316th Field Artillery Battalion had a problem after landings. Unable to observe their impact zones, they could not register their guns.

To remedy the situation, 1st Lt. Russell M. Dennis, T/4 Alex Bickoff, and T/5 Joseph L. Waligorski jumped on a tank and moved forward past the forward infantry positions to a better observation point. Here, ahead of the infantry, and atop a tank fully exposed to enemy small-arms and mortar fire, the three observed the battalion’s registration fires. They managed to complete the registration and safely return to friendly lines.

Meanwhile, the 322nd RCT had reached the 0-2 Line and was trying to close the gap between it and the 321st Infantry. Visual contact was finally established late in the afternoon, but a group of Japanese soldiers held positions between the two regiments and could not be dislodged. Physical contact would have to await daylight.

Indeed, as the first day on Angaur ended, General Mueller had much about which to be satisfied. His division had established a firm beachhead. Its communications, under Major William S. Houston’s 592nd Joint Assault Signal Company, were operating efficiently. Supporting artillery and armor were ashore and operating. Naval and air support had functioned as intended. With darkness now approaching, and knowing the Japanese preference for night counterattacks, the Wildcats dug strong defensive perimeters and awaited the new dawn.

As was usual with units new to combat, the tendency to fire at shadows or sounds took hold of the 81st Infantry Division on its first night in battle. In some areas it was so pronounced that the artillery commander, Brig. Gen. Beasley, and other commanders had to walk the front lines in danger of being shot by friend or foe alike, calming the men and assuring them that they were secure in the defensive perimeters. As it developed, the Japanese failed to take advantage of the newness of the Americans and only a few patrols and intermittent artillery fire disturbed the Wildcats’ first night ashore. But toward dawn Major Ushio Goto made his presence felt.

Goto had apparently needed the hours of darkness to assemble his counterattack force. Soon after 5 am, he launched his attack against Company B, 321st Infantry, with the intent of rolling up the American beachhead at Blue Beach.

Courage abounded among the American troops in their first action. Captain Wallace B. Moorman, to better control his command, Company B, 321st RCT, stood erect in the midst of enemy fire to encourage his men. He earned the Silver Star.

Nearby, Pfc. George B. Draughn, an attached machine gunner of Company D, was blinded in one eye by a shell fragment. Refusing evacuation, he remained with his gun crew until the enemy attack was turned back.

Private First Class Stephen W. White remained at his radio transmitting orders and information even as his platoon leader and platoon sergeant were killed in the same hole. Private William P. Curtis, Medical Department, crawled from hole to hole in the midst of the attack to provide first aid to at least eight wounded men. Another machine gunner from Company D, Pfc. Homer L. Johnson, volunteered to crawl forward to an abandoned machine gun. Under enemy small-arms fire he dismantled the gun and, cradling it in his arms, fired it as he crawled back to friendly lines.

Second Lieutenant Peter Chappetto of Company D saw a Company B rifle platoon leader killed and immediately assumed command of that platoon after receiving serious wounds that later resulted in his death.

Despite the need to withdraw 50 yards, Captain Moorman’s Company B held its line and forced the Japanese to flee back into the island’s interior. Occupying the enemy’s former positions were a depleted rifle company and a wounded battalion commander (Lt. Col. Lester J. Evans). The Americans had a firm grip on Angaur.

The 322nd Infantry had received a much less severe attack that same morning and soon turned the Japanese back. At 9 am, after a three-hour artillery preparation, the division again attacked with the 322nd directed to seize the 0-4 Line and the 321st Infantry the 0-2 Line. The 322nd pushed Lt. Col. Thomas D. McPhail’s 2nd Battalion past the tired 1st Battalion of Major White.

Once again the rough terrain proved as difficult as the Japanese. The 3rd Battalion found the enemy gone from its front and occupied the phosphate plant area, but the main opposition fell against the 321st Infantry. Colonel Dark’s regiment was hit by two counterattacks against Companies C and F but, with the support of air strikes, beat them both back.

Immediately, the 2nd Battalion took the offensive, but a second strong Japanese attack hit the 1st Battalion and forced a withdrawal. Once again air support and offshore shelling by an LCI (Landing Craft, Infantry) defeated the Japanese offensive.

Division headquarters landed on Red Beach at 7:55 am and by 9:25 General Mueller was ashore and directing the operation in person; at noon he assumed command of operations ashore from the Navy task force commander.

That same afternoon the 322nd Infantry achieved a physical link with the 321st, closing the dangerous gap between the regiments and trapping dozens of Japanese snipers and pillbox garrisons between them. The division’s Reconnaissance Troop was directed to eliminate these holdouts.

It was Lt. Col. Evans’s 1st Battalion, 321st Infantry that discovered why the landings at the Red and Blue Beaches had been lightly opposed. As they moved to clear Rocky Point, they discovered a perfectly developed and positioned defense system of pillboxes, dugouts, rifle pits, and interconnecting trenches. These were positioned to fire to the front or flanks, and each pillbox was defended by trenches or rifle pits to prevent infantry from making a close approach.

Trenches also provided a protected and covered access for reinforcements and supplies. Built of two walls of heavy coconut logs separated by several feet of space filled with sand and coral rock, they were all but impregnable to any infantry carried weapons. Never more than three feet above the surface and well camouflaged, they varied in size and shape depending upon the defenses they held. What they held was artillery, machine guns, and small arms manned by determined Japanese troops. They defended the best landing beaches on the island, the ones General Mueller had declined to land upon.

Colonel Evans quickly realized that a frontal attack on these prepared positions was senseless. Taking advantage of the Japanese failure to protect themselves from the rear, he left a small containing force to occupy the Japanese troops’ attention while the bulk of the 1st Battalion outflanked and isolated the enemy. Stopped briefly by a destroyed pillbox that had been reoccupied by the Japanese, the battalion advanced slowly over steep cliffs and through thick jungle.

Nearby, the 2nd Battalion reached the 0-2 Line and Lt. Col. Dallas A. Pillod’s 3rd Battalion and its attached tanks of Company B, 710th Tank Battalion cleared the phosphate plant area and moved to within 300 yards of Angaur’s west coast. But there were problems: when Company L of the 322nd RCT was firing on Japanese defenses, they were suddenly attacked by friendly aircraft.

Private First Class Richard F. Behm had just placed his machine gun in position when the American aircraft began to bomb and strafe his position. Undeterred, he continued firing his gun at an enemy pillbox until he knocked it out, only to be mortally wounded himself; he was awarded a posthumous Silver Star.

Upon learning of the “friendly fire” incident, which cost the division seven men killed and 46 wounded, General Mueller immediately ordered a cessation of all air attacks on the island. But the air attack, and the indiscriminate shooting from behind by service and supply troops reacting to the occasional sniper fire, kept the Wildcats distrustful of all friendly supporting fire for some time to come.

By late afternoon, however, elements of the 322nd Infantry were in sight of the town of Saipan, the island’s capital and largest city.

Back on the beaches, Lt. Col. Harold Taber’s 52nd Engineer Battalion and Lt. Col. Alan E. Gee’s 154th Engineer Battalion continued to improve the Red and Blue Beaches, respectively. Fighting off the occasional sniper and ducking intermittent mortar fire on the beaches, the two battalions of the 1138th Engineer Group cleared, organized, and operated the beach areas and supply dumps for the assault troops.

There was no counterattack during the night of September 18-19. Enemy infiltrators hit some units and small patrols were encountered, but the men of the 81st Infantry Division were now combat veterans and there was no recurrence of the previous night’s outbreak of indiscriminate firing. With dawn on September 19, the advance resumed.

This day the 321st Infantry had an easier time. With half a dozen infantrymen riding on tanks of Companies A and C, 710th Tank Battalion, they moved swiftly toward Middle Village, the second and only other settlement on the island, against light opposition. Three enemy pillboxes near Rocky Point were destroyed but enemy fire from Green Beach pinned down Company K for a while. Attempts to eliminate these defenses were halted by observed Japanese artillery and mortar fire.

Meanwhile, the 322nd RCT cleared Saipan village against mortar, rifle, and machine-gun fire and reached the 0-6 Line. In Colonel McPhail’s 2nd Battalion of the 322nd, Companies E and F assaulted Shrine Hill, capturing four 75mm guns and clearing numerous enemy caves and mine fields. As the attack progressed, T/Sgt. James F. Weston of Company E found himself in personal combat with an enemy brandishing a samurai sword. After tossing a grenade into a cave, Weston suddenly saw a sword-wielding Japanese officer come rushing out directly at him. Wounded by a blade slash, and also by grenades thrown by supporting Japanese soldiers, Weston held his ground and killed his attacker.

General Mueller made a personal reconnaissance of his front lines on the 19th. Having seen for himself the situation at the front of his assault regiments, he ordered their commanders to proceed in the attack without regard to objective phase lines; clearing the rest of the island before nightfall was the new goal.

The 321st Infantry put all three battalions on line and resumed the attack. Accompanied by tanks, the troops advanced against light resistance and reached a point about 800 yards from the southern tip of the island by 5:35 pm. Here they were stopped by a counterattack by some 200 Japanese soldiers. The attack came over open ground without supporting fire, and the Japanese were decimated.

At Green Beach, the 3rd Battalion finished clearing enemy defenses despite determined resistance by the Japanese.

Colonel Venable’s 322nd Infantry attacked Lighthouse Hill and ran into strong, well-concealed fortifications. American flanking movements met with limited success, and one was halted by murderous fire coming from the area of Lake Salome, one of the two lakes created by the strip mining. With darkness fast approaching and the ground unsuitable for defense, the 322nd withdrew to better defensive terrain and waited for the next day.

Late that afternoon, aircraft observed a group of rubber boats near the island’s southern tip. Exactly what the Japanese were attempting was unknown, but American artillery destroyed whatever was going on.

The day’s advance had split Major Goto’s forces into three isolated groups. One remained in the Green Beach defenses, another held the southern tip of the island, and a third was in the area Palomas-Romauldo-Black Beach.

For their actions thus far, the Wildcats received a Naval “Well Done” by the III Amphibious Force commander. One of those who earned the well done was Pfc. Clarence W. White of Company K, 321st Infantry, who exposed himself to enemy fire, using his light machine gun to pinpoint enemy positions for others to destroy. When some remained, he mounted the deck of a disabled tank and directed the tank’s fire from that position until he fell wounded. From an exposed position on the ground, White continued to indicate enemy targets using his machine gun until he was hit a second time and mortally wounded. He received the Distinguished Service Cross posthumously.

This day also saw the first Japanese prisoner of war captured. Seriously wounded, the soldier had been captured in a pillbox near Red Beach. Under interrogation by T/4 Saburo Nakamura and S/Sgt. James Kai, he reported that he had been in the pillbox for six days and that all troops except his battalion––1st Battalion, 59th Infantry, 14th Division––at a strength of a little over 1,000, had left for Babelthuap in June.

General Mueller had visitors this day, conducting ground force commander Maj. Gen. Geiger and naval force commander Rear Adm. Blandy over the battlefield.

September 20 opened with an attack by the 2nd Battalion, 322nd Infantry on Palomas Hill. Bitter fighting ensued but the Americans pushed their attack, knocking out pillboxes as they struggled up the nearly vertical slopes of the hill. By 9 am the battalion owned the hill, which they quickly discovered had been the enemy’s command post. Large quantities of weapons, including 75mm guns, were captured.

Meanwhile, Company G of the battalion, supported by tanks, was fighting its way toward Lake Salome, but Japanese defenses in the area were strong and the advance slowed. To the south, the 321st Infantry cleared enemy remnants in the southern end of the island. By midday the area was considered secured, and the outcome of the battle certain.

Another tour of inspection by General Mueller, accompanied by the corps commander, of the southern tip of the island confirmed the enemy’s destruction. At 10:55 am a radio message was sent to Corps Headquarters that read, “All organized resistance ceased on Angaur at 1034. Island Secure.”

The island may have been declared “secure,” but the resistance had not “ceased”; the battle went on. Major Goto had been caught unprepared for the American attack, expecting instead that they would come against his prepared defenses in the southern section of the island. Then the feint landing further convinced him that additional American landings were planned on the island, and he held much of his battalion in their positions, like those on Green Beach, awaiting an attack that never came.

Once he realized that the 81st Infantry Division had completed its landing operations, Goto began to pull his units together and move toward the northwest hills of the island, abandoning his southern defenses. Anything that could not be carried was discarded, including the artillery pieces captured at Paloma Hill. His troops took only what they could carry into the rugged northwest corner of Angaur and prepared themselves for the “defense in depth” phase of the island’s defense.

The northwest corner of the island was like the difficult coral cave area on the island of Biak, New Guinea, that had delayed the 41st Infantry Division for weeks just a few months earlier. Filled with coral pinnacles, shallow shelves, and ridge lines running in every direction, Angaur’s northwest section was filled with natural crevices and covered by large tropical trees and thick jungle undergrowth. It was a defender’s dream and an attacker’s nightmare.

So rough was the terrain that the tanks of the 710th Tank Battalion could not be used in the assault. In the heavy jungle and bleak coral landscape, the incredible heat and humidity of the island intensified its toll on the attacking Americans. Colonel Venable also noted that evacuating casualties would be a difficult operation and so pulled his regiment back to reorganize for a new attack the following day. By this time, the division intelligence section estimated that about 850 enemy had been killed, leaving about 350 cornered in the northwest.

Based on this estimate,General Mueller believed that a reinforced regiment could clear the rest of Angaur and so assigned Venable’s 322nd Infantry that job. The attack on September 20 immediately faced problems, however. Enemy automatic weapons and small-arms fire from heights to the front and from the right flank hit Major White’s 1st Battalion. The supporting tanks could not get past the difficult ground to assist the infantry. Then a swamp near Lake Aztec forced the infantry to move along a line of advance that the Japanese had already planned as a fire zone. Although the advance was difficult and dangerous, the Wildcats pushed forward and made progress.

The next major obstacle was Lake Salome, or what was later called “Wildcat Bowl.” The first move toward the Bowl by Company G and self-propelled guns of the regiment’s Cannon Company was soon halted by land mines and an enemy antitank gun that knocked out one of the guns and wounded the entire crew. Colonel Venable immediately sent up a platoon of medium tanks but they could not get through a defile that led to the Bowl.

With his advance stalled, Venable ordered Company B to attack from the east. Forced to cut their way through thick undergrowth, Company B’s attack soon bogged down. Faced with no alternative, Venable ordered both groups to withdraw while artillery registered on the Bowl. By the end of September 20, the 322nd Infantry firmly disagreed with General Mueller’s estimate that the Japanese on Angaur were defeated.

Later intelligence estimates indicated that Major Goto had more than 750 men defending the Wildcat Bowl. He had recently received orders from General Inoue that no final banzai attacks were to be launched and that the defense in depth tactic was to be carried out to the end.

On September 21 the regiment went back on the attack. Led by Companies E and F, the 322nd tried to break into the western side of the enemy defenses. Supported by a naval air strike and the division’s 155mm gun battalion, which had to relocate because once again the range was below the minimum for the guns, the infantry attacked, confident that the enemy defenses had been damaged, if not destroyed. They quickly received a rude surprise.

Tanks attempting to support the advance were blocked by a knocked-out Cannon Company vehicle, which had to be towed away after attempts to destroy it with demolitions failed. Meanwhile, the infantry came up against strongly placed enemy defenses, including mortars, light artillery, machine guns, and small-arms fire, all coming from hidden positions with mutual support.

Eventually eight tanks and a platoon of infantry from Company G managed to get into the Bowl; only scattered small-arms fire opposed them. But the tanks were forced by the terrain to follow the track of one of the narrow-gauge railways built by the Japanese. These were on raised beds and two tanks slid off the banks. Both became useless and had to be abandoned.

Three other tanks, guided by Private Oliver C. Ferguson of the 710th Tank Battalion, moved into the Bowl and provided supporting fire while the Company G platoon worked along the eastern rim of the Bowl. An enemy antitank gun was located and knocked out before it could open fire, but little in the way of targets could be identified.

Despite the Americans’ artillery barrage, the heavy vegetation remained, hiding the Japanese. As a result, enemy fire and difficult terrain continued to slow the advance. Because the tanks could not leave the railroad cut, tank-infantry cooperation was impossible. Patrols from other companies did, however, reach the northwest tip of Angaur, surrounding the Japanese within Wildcat Bowl. While the 321st Infantry cleared the rest of the island of snipers and holdouts, the 322nd Infantry remained focused on reducing Major Goto’s main force in and around Wildcat Bowl.

Meanwhile, the division’s 3rd Regiment, Colonel Arthur P. Watson’s 323rd Infantry, still offshore, left Angaur’s waters to seize Ulithi Island. Later that afternoon, Admiral Fort and Generals Smith and Geiger arrived at division headquarters to meet with General Mueller. Things were not going well over at Peleliu and Mueller was requested to furnish one regiment to assist the Marines. The 81st’s assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Marcus P. Bell, was ordered to take the 321st Infantry to Peleliu as soon as possible.

With the 321st preparing to leave Angaur, the attack was renewed on September 21. It soon turned into a battle of attrition, with the Americans forced to attack the hidden Japanese and knock out one position at a time. With machine guns, rifles, antitank guns, and mortars firing from hidden positions using smokeless, flashless powder, and usually mutually supporting, Major Goto’s defenses could withstand everything but a direct attack.

Often, even after a cave had been knocked out, it would come back to life after the Americans had bypassed it. Using fire and movement, employing flamethrowers and demolition charges, the 322nd Infantry slowly but steadily knocked out the remaining Japanese within Wildcat Bowl, but it remained a costly operation. Three tanks supporting the infantry at the railway cut were fired on by antitank guns. Colonel Venable, standing near them and observing his regiment’s attack, was hit by shell fragments and his arm was nearly severed. Next to him, his radio operator, Sergeant William E. Sherman, was killed by the same gun. Venable was quickly evacuated to the 17th Field Hospital. Lt. Col. Ernest H. Wilson, the regimental executive officer, assumed command of the 322nd Infantry.

Once again the infantry had to withdraw at darkness. One tank had been so badly damaged that it had to be abandoned, and another tank in front of it could not get past the disabled tank, so it, too, had to be destroyed. For a hard day’s work, an estimated 75 Japanese had been killed and two taken prisoner. One of these, a Private Ikeda, a cook for the battalion, later broadcast surrender appeals to his comrades within Wildcat Bowl.

Only two of Major Goto’s men responded to Ikeda’s appeals, and both were soon prisoners of war. They reported that their comrades were short of food and water. Morale remained excellent and the bulk of the Japanese force had no intention of surrendering. Under interrogation, the POWs estimated the remaining force at 400 men.

After attacking for seven straight days, Sunday, September 24, was a day off for the exhausted infantrymen of the 322nd Infantry. The engineers of the 306th Battalion built roads up to the front lines to expedite resupply and evacuation of the wounded.

While their artillery bombarded the Lake Salome-Wildcat Bowl area all day long, the men of the 322nd listened to broadcast appeals for the Japanese to surrender while they themselves rested, repaired equipment, and moved to new assault positions.

The Wildcats returned to the attack the next day, and again the next. The battles were characterized by actions such as that of Pfc. Lester H. Klatt of Company F. While moving downhill toward the enemy, he observed a machine-gun position on the right flank that could enfilade his entire company. Klatt immediately rushed the position, threw a grenade, and then fired his rifle until the crew was killed and the gun captured.

In another instance, 2nd Lt. Robert G. Holsinger found his platoon pinned down by two mutually supporting machine guns. Terrain made an attack nearly impossible, but Holsinger led a squad against one of the guns until he fell mortally wounded. But his attack succeeded and the platoon knocked out both enemy guns.

By September 30 the Japanese had been squeezed into a restricted area near some cliffs in the northwest corner of the island, but still the fighting raged fiercely. When a patrol of Company L was attempting to clear a chasm of the enemy, they were ambushed by automatic weapons and rifle fire; three men were killed and two others wounded. Pfc. James G. Ramsey, himself wounded, volunteered to remain behind and cover the withdrawal of the wounded men using his automatic rifle. When he ran out of ammunition, he picked up a submachine gun from one of the dead and used it until he was mortally wounded. His courage earned him a posthumous Silver Star.

Private Marion Clark, also of Company L, was with another small group when it was attacked with grenades. Though severely wounded, he took up a flanking position with his Browning Automatic Rifle and stood upright to fire effectively on the attacking Japanese, holding his position until he died of his wounds. Clark’s Distinguished Service Cross was also awarded posthumously.

And so it continued. A flag-raising ceremony was conducted near Red Beach and congratulations from all sources poured into General Mueller’s headquarters. But barely two miles away vicious combat continued. Not even field grade officers were immune, as when Major Louis K. Har-throng, commanding the 1st Battalion since September 23, was killed by a sniper while directing the forward elements of his battalion. Major Michael Gussie, who replaced him, was likewise seriously wounded by an enemy grenade on October 20.

Major Goto was also killed on October 20 while attempting to infiltrate his remaining troops through American lines to Lighthouse Hill, where he planned to build a raft and escape. That night the remaining Japanese tried desperately to avoid death or capture. The next morning 10 Japanese soldiers surrendered, but for weeks afterward individual Japanese were either killed or captured throughout the island.

Technical Sergeant Frank J. Becker of Company L led a night patrol to recover the bodies of American dead. Becker found that the enemy position could be knocked out by explosives, and the following day he led a patrol back to place demolition charges. Discovered by the Japanese, several men in Becker’s party were wounded. Becker directed the withdrawal of his men and evacuated a wounded man to safety.

Becker had earlier occupied an advance position behind enemy lines and had harassed them with fire for five days. But on October 21 his luck ran out; he was killed while leading a portion of his company to a new location. His Distinguished Service Cross was posthumously awarded.

Like many Pacific War battles, the Battle of Angaur ended more with a whimper than a bang. There were no banzai attacks, and individual Japanese fought until killed well into November 1944. But for all intents and purposes, the campaign ended October 23, 1944, although both General Geiger and General Mueller had declared it over days earlier. Some 1,330 Japanese had been killed and 59 captured.

Total battle casualties for all American units fighting on Angaur came to 264 men killed and 1,355 wounded. There were also 244 cases of battle fatigue and 696 hospital cases from sickness and disease. During the battle some 900 men fell due to heat exhaustion. About 183 natives were freed from Japanese imprisonment.

Meanwhile, the combat troops had moved westward to other islands and other battles.

Today, beautiful and peaceful Angaur has fewer than 200 permanent residents and the capital has been moved from Saipan village to Ngeremasch. Phosphate mining ended in the 1950s. The few visitors who come to Angaur do so primarily for the surfing and for technical diving on the USS Perry (DMS-17), 240 feet down, sunk by a mine off the southeast coast on September 13, 1944. Destroyed and abandoned vehicles, equipment, guns, and other military artifacts are slowly rusting away in the jungles, mute reminders of the savagery that took place there seven decades earlier.

The Battle of Angaur today remains a footnote in the history of World War II, but it is remembered by the men who fought there as one of the most savage and difficult of all encounters.

There are some military critics who have observed that that the attack on Palau was quite unnecessary. There was no Japanese air force presence of significance on the islands and they had no way to transport to the Philippine island of Mindanao to interfere with operations there. An analysis of this action after the war tends to confirm this position.

As with many of the island battles leading up to the invasion of the Philippines, many U.S. (and Japanese) troops were killed and wounded quite unnecessarily; all to feed McArthur’s humongous ego! After all, he promised that “I will return” to the Philippines. The invasion of the Philippine Islands was totally unnecessary, but McArthur somehow convinced Truman and others that it needed to be done.

McArthur exhibited the same self-centered and egotistical behavior in the Korean War, which again got thousands upon thousand of U.S. troops killed and injured in senseless actions.

Tim,

Just about everything you wrote is incorrect! Truman was not the President when the decision was made to invade the Philippines, FDR was. You can read the reason why we invaded the Philippines here: https://history.army.mil/books/70-7_21.htm

Ian W. Toll in his Pacific War Trilogy also tells the reason why we invaded the Philippines.

There was no reason to take Peleliu. Admiral Halsey tried to convince Admiral Nimitz to cancel the operation but, he refused.

Mike