By John Walker

In November 1177, Saladin launched his first significant military campaign against a crusader state. With 26,000 men, siege engines, a huge baggage train, and his own personal force of elite Mamluk bodyguards, Saladin marched his Ayyubid army across the Sinai Desert from Egypt into southern Palestine. Saladin’s overwhelming numerical superiority over his foe had made him confident enough to allow his troops to disperse into the vast, open countryside, where they plundered, foraged for food, and looted Christian settlements at Ramla, Lydda, and Arsuf.

King Baldwin IV, who was suffering from aggressive leprosy, rapidly cobbled together his remaining forces, approximately 350 mounted knights and several thousand foot soldiers, and with the notorious Christian Prince Raynald of Chatillon in command, marched to Ascalon. There, in the face of Saladin’s huge army, Baldwin withdrew his army into the safety of the fortress, leaving the road to Jerusalem wide open. Approximately 84 Knights Templar commanded by Master Odo de St. Amand marched from Gaza to join the Christian forces.

On November 25, with the roads muddy from recent rains, Saladin and the vanguard of his army were pushing east toward Ibelin. Near the rear of the column, his baggage train and siege engines became mired in mud near the mound of al-Safiya, not far from Montgisard. Suddenly, the sultan of Egypt and Syria was shocked to see a small enemy force, with Knights Templar in the vanguard, forming up on a nearby hill. Baldwin’s army had left Ascalon and marched to block Saladin’s path to Jerusalem. In his hubris, Saladin had failed to leave scouts behind to monitor his enemy’s activities.

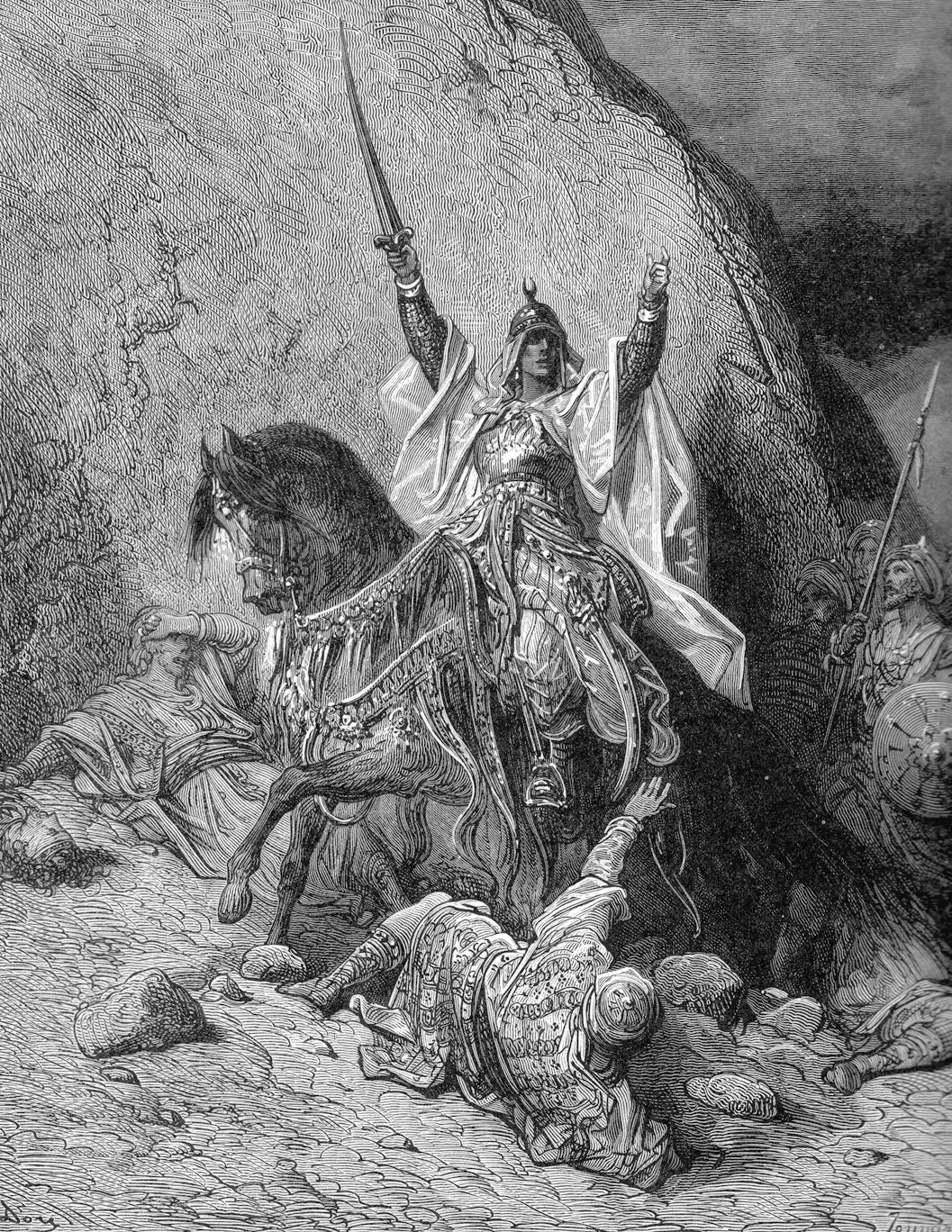

Saladin was taken completely by surprise. His army was in disarray, some of it held up with the stalled baggage train, others still absent raiding the countryside. Both his men and horses were exhausted after the long march from Egypt and their subsequent raids. Saladin raced to assemble his elite troop of personal guards—between 600 and 900 strong—while his nephew and chief commander, Taqi ad-Din, attempted to form the main body into lines of battle. Saladin tried to anchor his line on a nearby hill, but it was too late; as the Christian columns came crashing down on the confused Ayyubid ranks, Master Odo and his Knights Templar shattered the center of Saladin’s line. Unable to form ranks or mount any effective resistance, the much larger Muslim force was thrown into confusion and began falling back. Many of Saladin’s soldiers had already fled the field before the full force of the Christian charge struck; those who stood and fought were all but destroyed. Taqi ad-Din’s son, Ahmad, was killed early in the fighting, and the loss of Ahmad and other high-ranking officers disheartened the Ayyubid soldiers. Vicious fighting raged as the Christian knights turned upon Saladin’s elite force of Turkish slave soldiers and routed them as well, after which Saladin managed to flee the carnage.

Odo led his Knights Templar in a charge directly at Saladin’s household troops. “Recognizing the battalion of troops in which Saladin commanded many knights, they manfully approached it, immediately penetrated it, incessantly knocked down, scattered, struck and crushed,” wrote Ralph of Diss, an eyewitness to the battle. “Saladin was smitten with admiration, seeing his men dispersed everywhere, everywhere turned in flight, everywhere given to the mouth of the sword. He took off for his own safety and fled, throwing off his mail shirt for speed, mounted a racing camel and barely escaped with a few of his men.”

Saladin’s huge supply train was captured; as they fled, many Muslim soldiers abandoned their weapons, armor, and booty. Losses were heavy on both sides: Baldwin’s army suffered 1,100 men killed and 700 wounded, while no more than one-tenth of Saladin’s invasion force made it back to Egypt. The sultan’s men suffered mightily on their long, hot trek home across the desert. Bedouins constantly harassed them, and any who made the mistake of stopping in villages to beg for food and water were slain or handed over to the Christians as hostages. When Saladin returned to Cairo, he circulated the lie that the Christians had been defeated. It would not be the last time he and his armies would find themselves battling the fierce and supremely disciplined warrior monks of the Christian military orders.

The First Crusade ended with the holy city of Jerusalem back in Christian hands and the founding of a number of crusader states in the Near East, the Kingdom of Jerusalem foremost among them. These nascent realms lacked the necessary military force to maintain more than a tenuous hold over their territories, yet in the religious fervor of the time tens of thousands of Christians from all over Europe began making pilgrimages to the Holy Land. The 35-mile journey from the Mediterranean seaport of Jaffa to Jerusalem, a two-day trek inland along a dangerous mountain road surrounded at all times by brigands, wild animals, and Muslim armies, was fraught with peril for travelers.

In 1119, Hughes de Payens, a French nobleman, knight, and veteran of the First Crusade who had taken religious vows upon the death of his wife, offered to recruit eight other knights—all of them related to him by blood or marriage—to devote their lives to the care and protection of Christian pilgrims traveling through the Holy Land and to form a religious military order for that purpose.

Jerusalem’s King Baldwin II approved of this radical new concept—a hybrid army of professional soldiers living as poor monks in service to Christianity—and awarded them lodging in a captured Islamic shrine, the al-Aqsa mosque near the Dome of the Rock, the original site of the Temple of Solomon. In front of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, de Payens and his comrades took vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity, and the Order of the Knights Templar became a reality. Its mission would grow into providing much-needed military support to Christian states in the Levant as well.

Although the Knights Templar were at first opposed by some who questioned the paradoxical idea of a religious military order and later by those who envied their enormous wealth and influence, many influential secular and religious leaders championed them. One prominent advocate in the early years was Count Hugh of Champagne, a French landowner and the feudal liege lord of Hughes de Payens. Count Hugh became a Templar in 1125 and later provided the site in northeastern France where the Council of Troyes was held in 1129. Pope Honorius II convened that council at the request of Bernard of Clairvaux, the abbot of the Cistercian monastery of Clairvaux and by far the most influential and charismatic figure of the medieval Roman Catholic Church at that time.

After the council recognized and confirmed the Knights Templar as an ecclesiastical body of the Church, Bernard helped write the Latin Rule, modeled after the Benedictine Rule, to guide their conduct. Knights Templar were awarded their own distinctive dress, a plain white tunic to which a red cross was added in 1147. As a symbol of their humble beginnings, the order’s seal depicted two knights riding on a single horse. After the council adjourned, massive donations of land and money began pouring into the order’s coffers, and thousands of Christian men hoping to join the order began the trek to Jerusalem. Less than eight months after the Council of Troyes adjourned, the order dispatched 300 mounted knights, with their retainers and huge entourage to the Holy Land. By the mid-12th century the constitution of the order and its basic structure were in place; it was headed by a grand master who served for life and oversaw all facets of the operation, from military operations in the East to the order’s holdings and operations in the West.

In early 1139, even more unprecedented privileges were bestowed upon the order when Pope Innocent II issued a papal bull that exempted the Knights Templar from all tithes and taxes, allowed them to pass freely across any borders, and subjected them to no one’s authority save that of the pope. It was a remarkable validation of the Knights Templar and their mission; Bernard of Clairvaux became the order’s patron. Western monarchs realized the Knights Templar could play a valuable role defending their territories against non-Christians as well, and Templars were given frontier land to defend on the Iberian Peninsula and in Eastern Europe.

Other Christian landowners, well away from the frontiers, gave huge land endowments to the Knights Templar to both support their mission and to gain divine favor for themselves. While the main military operations of the Knights Templar took place in the Near East and the Iberian Peninsula, all across Europe Templars were soon to be found operating mills, farms, mines, and other commercial operations to support the order’s efforts on the frontiers. Active orders were established in England, France, Scotland, Hungary, Portugal, and elsewhere. The Knights Templar eventually held vast tracts of land across Europe and controlled fortresses in Near East cities including Gaza, Acre, Tyre, Sidon, Beirut, Tripoli, and Antioch. In 1130, the order was established on the Spanish peninsula, the scene of the first Knights Templar military campaign against the Moors.

The majority of the order’s warrior monks were not knights—only a small minority of Knights Templar were anointed knights; they were called servientes in Latin or sergents in French, generally translated as sergeants but literally meaning servants. Generally recruited from the lower classes, they wore black tunics and supported their brothers on the battlefield as light cavalry or infantry, while other brothers served in noncombat roles as laborers, engineers, armorers, and craftsmen. The knight brothers, who came from the military aristocracy and were already trained in the art of war, assumed elite leadership positions in the order and served at royal and papal courts. Only the mounted knights wore the distinctive regalia, a white surcoat emblazoned with a red cross. A third class, chaplains, eventually was added. They were responsible for addressing the spiritual needs of other members.

In a matter of years the order rivaled the kingdoms of Europe in military might, economic power, and political influence. The Knights Templar built fortifications throughout Europe and in the Holy Land and were heavily involved in economics, finance, and banking. The order’s military strength enabled it to safely collect, store, and transport bullion to and from Europe and Outremer and their network of storehouses and efficient transport organization made them attractive as bankers to kings, pilgrims, and the Church. A pilgrim could deposit funds at a Knights Templar site in his home country and then travel across Europe and into the Levant, drawing funds from his account when needed. One of the most controversial of the order’s activities was granting loans. The Church had strict laws against charging interest, but the order circumvented that by charging rates. The Church looked the other way, yet another significant concession to the order. By 1300, the Knights Templar numbered in the tens of thousands across Europe and the Holy Land, manning a massive system of Templars and civilians in the West and supporting the massive military efforts in the East. At its peak in the Holy Land, the order often numbered as many as 20,000 members, of whom no more than 1,500 to 2,000 would have been mounted knights.

The Knights Templar, whose knights were trained and anointed long before they joined the order, quickly gained a reputation as the best-trained, most fanatical soldiers of the crusading era. Knights Templar were schooled in warfare from an early age and boasted the finest equipment, horses, and support system of any army in the Levant. They had no fear of death since they believed death on the battlefield in the service of God guaranteed them entrance into heaven, and as true holy warriors they fought with seemingly suicidal fervor. The Knights Templar were first integrated into main Christian armies or held back as a special reserve. Later, when their renown grew, they were used as shock troops, the mounted spearheads of attacks meant to break the enemy’s front ranks and allow the main battle force to advance.

The ascendency of the religious military orders was sealed by events of the Second Crusade when France’s King Louis VII and Pope Eugenious III convinced the Knights Templar to accompany the French Army to the Holy Land. The Knights Templar fought and behaved admirably during the hazardous journey from Constantinople across Asia Minor to Antioch. The presence of a German force under King Conrad III created some difficulty since the combined forces lacked a single, competent combat commander and therefore lacked overall coordination and cohesion. As they passed through Anatolia, King Louis lost control of his army; to restore order he surrendered his command to Knights Templar Master Everard des Barres. After des Barres divided the army into units, each under the command of a Templar to whom they swore absolute obedience, the coalition army then fought its way successfully to Attalia.

The mid-12th century witnessed the development of an important trend among the Franks in the Holy Land. Secular lords began to donate castles to the military orders and to rely on them to defend the territories included in those grants. The baronage realized that the cost of maintaining sufficient troops and supplies in those castles was simply too high; it was cheaper to contribute excess property to the military orders than to be forced to defend it. It is estimated that by the time of the Battle of Hattin in 1187, the Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller, the latter another religious military order whose roots were established before the First Crusade, held about 35 percent of the lordships in the Outremer.

The Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller served as vanguards and rear guards for Christian columns on the march throughout the Crusades. Kings Louis VII, Richard I, and Louis IX all entrusted Knights Templar with the task of instilling and preserving order within their otherwise poorly disciplined armies, both on the march and on the battlefield. The military orders proved invaluable to King Richard during the Third Crusade, never more so than when he relied on their steadiness and discipline during the rugged march south from Acre into southern Palestine in September 1191. During the Battle of Arsuf, King Richard’s army was vulnerable to flank attacks by Saladin’s Turkish and Kurdish cavalry, and it was thanks to the iron discipline of the Knights Hospitaller that the attackers were beaten back and the coherence of the Christian column maintained. On the march, Richard placed Knights Templar at the front of his army and Knights Hospitaller at the rear. Infantry armed with crossbows and spears guarded the flanks of the column on the march. King Richard directed his marching columns to maintain their cohesion at all costs while Saladin’s cavalry wore itself out in repeated attacks. Upon Richard’s order, his cavalry would make sorties designed to sweep the enemy from the field.

The pattern was repeated countless times, beginning with wave after wave of lightly armed skirmishers harassing the Christian army’s column, followed by massive attacks conducted by Saladin’s light cavalry divisions, their riders firing short bows and swinging scimitars and battle axes. The Christian column managed to hold firm, but the Knights Hospitaller came under intense pressure at the back of the column. Unwilling to endure any further losses of men or horses, the Knights Hospitaller finally attacked without Richard’s permission, carrying the French division on their right with them into the fray. King Richard and the rest of the army followed, supporting the Knights Hospitaller charge and shattering Saladin’s columns. Arsuf was a tremendous moral and tactical victory for the Christians and a clear blow to Saladin’s prestige, a small repayment for the 235 Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller he summarily slaughtered after the Christian defeat at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. Saladin had paid his soldiers 50 dinars for each captured knight from the two military orders they turned over to him after the Battle of Hattin. Wary of their unwavering discipline, ferocity, and lack of desire for material possessions, Saladin repeatedly vowed to his fellow Muslims that he would kill all of the soldiers from the two orders in the region.

King Baldwin IV’s win over Saladin at the Battle of Montgisard in 1177 had been an astonishing tactical victory against crushing odds for the Christian army and a costly defeat and psychological setback for Saladin. A decade later, though, Saladin inflicted a devastating defeat on the Knights Templar at a massive fortress they were building at Jacob’s Ford on the Jordan River. Saladin razed the structure and killed 80 knights and 750 sergeants, some during the battle and some executed afterward.

Saladin’s continued success eventually helped tip the balance of power in the Holy Land and signaled the first step in the decline of the Knights Templar. After the Third Crusade failed to capture Jerusalem, a number of increasingly futile crusades exhausted the treasuries of Europe and dampened the spiritual ardor that had once so vibrantly animated the cause. Throughout the 13th century, the Knights Templar were forced to fight holding actions to protect their shrinking territories in the Near East and their reputation in Europe. Eventually, their once vast domain along the eastern Mediterranean coast was reduced to just a single fortress at Acre, which had served as the de facto capital of the remnant Kingdom of Jerusalem for a century following the Third Crusade. In 1291, Acre was captured by the forces of the Mamluk Bahri Sultanate of Egypt. In 1302, the crusading period in the Near East came to an end, and the Christians had essentially been driven from the region.

The origin of the Knights Hospitaller can be traced to the early 11th century when a group of Italian merchants received permission from the Muslim rulers to maintain a Latin church in Jerusalem. As an offshoot of the church, a hospital was established to provide care for poor, sick, or injured Christian pilgrims. Shortly after the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, Blessed Gerard Thom, who was the master of the hospital at the time, founded the Knights Hospitaller.

After Gerard was confirmed by papal bull in 1113, he proceeded to acquire territory and revenue for the order throughout the Kingdom of Jerusalem and beyond. By 1130, the order was employing mercenaries to protect pilgrims from bandits and by 1136 was providing armed Knights Hospitaller to escort travelers as well as assume responsibility for the defense of part of the frontier. In 1140, the Knights Hospitaller took over the castle of Bethgibelin near Ascalon at the request of King Fulk I and his barons.

Although there is some uncertainty as to exactly when and how the Knights Hospitaller became a true military order, they were certainly militarized by the 1160s when they took part in Christian expeditions against Egypt. Like the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitaller were monks and swore vows of personal poverty, obedience, and celibacy. The order included brother chaplains and brother infirmarians who did not take up arms. At the height of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Knights Hospitaller held seven great forts and 140 estates in the region; their main bases of power in the kingdom and in the Principality of Antioch, respectively, were Krak des Chevaliers and Margat castles.

In 1217, still with the intention of capturing Jerusalem, the papacy launched the Fifth Crusade, though the means of doing so was to first attack Egypt. The Knights Templar were involved in this new crusade from its beginning, with their treasurer at Paris overseeing the donations that were to fund the expedition. Forces commanded by King Andrew of Hungary and Duke Leopold of Austria joined with those of King John Brienne of Jerusalem, the latter including Knights Templar, Knights Hospitaller, and Teutonic Knights. The Teutonic Knights were a new military order founded along the lines of the Knights Templar by Germans who participated in the Third Crusade. With no single outstanding leader among this coalition force, overall command of the Fifth Crusade was given to the papal legate Pelagius, a man with no military experience. In 1219, the crusaders nevertheless captured the port of Damietta in the Nile Delta thanks largely to the Knights Templar, who not only fought admirably on horseback, but also demonstrated a remarkable talent for innovation. Adapting their engineering and tactical skills from the arid conditions of Outremer to the watery landscape of the Nile Delta, they commanded ships and built floating pontoons crucial to the victory. The loss of Damietta so unnerved Sultan of Egypt al-Kamil, who was Saladin’s nephew, that he offered to trade it for Jerusalem. But the Knights Templar Grand Master argued that the Holy City could not be held without controlling the lands beyond the Jordan River. The crusaders rejected the offer and continued their Egyptian campaign. Even after another army—led by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II—failed to appear, Pelagius impatiently urged the crusaders to advance up the Nile toward Cairo. United under the command of an experienced combat leader, the Fifth Crusade might have had a chance of success, but at al-Mansurah, al-Kamil blocked thecrusaders’ rear, opened the sluice gates of the irrigation canals, and flooded the Christian army into submission. In 1221, Pelagius agreed to give up Damietta, not in exchange for Jerusalem but to save the lives of the crusaders who immediately evacuated Egypt and returned to Acre.

The brief Sixth Crusade began in 1228, just seven years after the failure of the Fifth Crusade. It involved little fighting. The crusade’s leader, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II of Germany, did manage, through diplomatic maneuvering, to regain temporary control of Jerusalem for the Christians.

When war broke out between the Ayyubid rulers of Egypt and Syria in the spring 1244, the Knights Templar persuaded the barons of Outremer to intervene on the side of the Damascene ruler Ismail. The alliance was sealed when the Franks were offered a share of Egypt if Sultan al-Salih Ayyub was defeated. Continuing factionalism in Cairo meant that al-Salih could not rely on his regular army, but he took steps to counter that by purchasing Mamluks in large numbers. These slave soldiers were mostly Kipchak Turks from the steppes of southern Russia. Bought, trained, and converted to Islam, they became al-Salih’s powerful private army. Al-Salih also bought the support of Khwarezmian Turks, ferocious mercenaries based in Edessa after being displaced from Transoxiana and parts of Iran and Afghanistan by the Mongols. In June, some 12,000 Khwarezmian horsemen swept southwest into Syria. Deterred by the formidable walls that ringed Damascus, they rode into Galilee and captured Tiberius. On July 11, they broke through the feeble defenses of Jerusalem and brutally massacred everyone who could not retreat into the citadel. The surviving defenders emerged from the citadel six weeks later after being promised safe passage to the coast. The garrison, however, together with the city’s entire Christian population—6,000 men, women, and children—left the city but were soon cut down by Khwarezmian swordsmen. Only 300 survivors made it to Jaffa. For good measure, the Khwarezmians ransacked the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, destroyed the bones of the former kings of Jerusalem entombed there, and put the structure to the torch. After that, they burned all the other churches in the Holy City and pillaged its homes and shops. They left the smoking wreckage of the city and marched to join al-Salih’s Mamluk army at Gaza.

Christian forces scattered throughout the castles of Outremer responded by gathering at the port of Acre. Not since Hattin had such a considerable Frankish army been put into the field; its numbers included more than 300 Knights Templar, 300 Knights Hospitaller, a small force of Teutonic Knights, 600 secular knights, and a proportionate number of sergeants and foot soldiers. To these were added the more numerous, if lighter-armed, forces of their Damascene ally under the command of al-Mansur Ibrahim, as well as a contingent of Bedouin cavalry. On October 17, 1244, the Christian-Muslim army drew up before the smaller Egyptian army outside Gaza on a sandy plain at a place called La Forbie. The Franks and their allies attacked, but the Egyptians stood firm under the command of their Mamluk commander Baybars (not Baybars I, who later became the fourth Sultan of Egypt), and while the Franks were pinned in place the Khwarezmians tore into the flank of al-Mansur Ibrahim’s forces. After the Damascene forces turned and fled, the Christians fought on bravely but within several hours their entire army was destroyed. At least 5,000 Franks died in the battle, among them 260 to 300 Knights Templar and an equal number of Knights Hospitaller, while more than 800 Christian soldiers were captured and sold into slavery in Egypt. The catastrophe was comparable to Hattin, and when Damascus fell to al-Salih the following year it seemed as though time might be running out for Christian Outremer.

The Seventh Crusade to the Holy Land was led by King Louis IX of France, who landed in 1249 with his army at the Egyptian delta port of Damietta. In February 1250, the French advanced toward Cairo but suffered crushing losses at the Battle of al-Mansurah due to the impetuosity of the king’s brother, Count Robert of Artois. Artois ordered the Christian van of mounted knights to charge into the city, where they were trapped within the narrow streets. Artois was killed, and the Knights Templar alone lost 280 knights, a terrible blow. King Louis’s main army was almost destroyed by an Egyptian force led by Baybars I (the Mamluk commander who later became the fourth Sultan of Egypt). King Louis, rather than retreating to Damietta, opted to remain and besiege al-Mansurah, which led to starvation and death for the scurvy-ridden Christians, not the Muslims inside the city. King Louis finally retreated toward Damietta but was overtaken. At the Battle of Fariskur, the crusader army was destroyed and the king captured. Louis was released only after a huge ransom was paid, to which the Knights Templar, who as bankers of the crusade had a treasure ship offshore, refused to contribute.

When the remnant Kingdom of Jerusalem fell in 1291, both military orders sought refuge in the Kingdom of Cyprus. The Knights Templar and Knights Hospitaller had both built castles on Cyprus, and when the Franks were finally driven from Outremer the island became a sanctuary for both orders. It was the Knights Templar, whose mission had been the protection of Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land, who felt the loss most severely. While charitable work took precedence for the Knights Hospitaller, the Knights Templar were founded as a knighthood, and they had smoothly made the transition to that of a military order whose primary mission was to fight the infidel. To avoid becoming enmeshed in Cypriot politics, Hospitaller Master Guillaume de Villaret created a plan for the order to acquire its own temporal, sovereign domain—the island of Rhodes, which was part of the Byzantine Empire. His successor, Fulkes de Villaret, executed the plan, and in August 1309, after two years of campaigning, Rhodes and a number of neighboring islands surrendered to the Knights Hospitaller. On Rhodes, the order became even more militarized when it began conducting large-scale naval operations.

Cast out of the Holy Land, the Knights Templar found themselves in limbo. France had traditionally been a stronghold of Knights Templar power, but in a tragic twist of fate the Templars found themselves under attack by a new and unremitting enemy, the ruthless King Philip IV. Philip had inherited the Champagne region in France and did not want the Knights Templar, now a professional army without a base or a battlefield to fight on, to create their own sovereign state close by. The Knights Templar had indicated an interest in founding their own monastic state, such as the Teutonic Knights had done in Prussia and the Knights Hospitaller were doing in Rhodes. King Philip’s campaign against the Templars—in truth a naked attack against the papacy and Catholic Church by a secular French monarch—began with his management of the selection of his handpicked French favorite, Cardinal Bertrand de Got, as Pope Clement V in 1305, a victory that ushered in a long period of French domination of the papacy. After inheriting vast debts from his father’s wars, King Philip had himself squandered huge sums warring in England and Flanders, stolen from both Jewish and Italian bankers, and debased the currency.

Having engineered the election of the pope and the relocation of the papal court to Avignon in France and intent upon getting his hands on Knights Templar cash and precious metals, King Philip moved against the Knights Templar with brutal dispatch. On October 13, 1307, at his order, between 3,000 and 5,000 French Knights Templar were arrested, including Grand Master Jacques de Molay. Soon Christendom was rocked by lurid allegations—blasphemy, sacrilege, and sodomy—against the warrior monks. Under severe torture, de Molay and others confessed to such crimes. Philip was able to arrest and charge the Knights Templar with heresy through the use of a loophole in the law going back to the time of the Cathars and their heresy trials 80 years earlier. But once freed, de Molay recanted his confession.

A majority of contemporary historians are convinced of the innocence of the Knights Templar, especially after the discovery in 2001 of a document known as the Parchment of Chinon in the Vatican’s secret archives, where it had been lost. The document indicates Pope Clement V secretly absolved the Knights Templar of the false charges against them but was forced by King Philip and popular frenzy to disband the order in 1312 and allow de Molay and fellow Knights Templar Geoffrey de Charney (judged to be relapsed heretics) to finally be burned alive in Paris in 1314. They were the last victims of a profoundly unjust, corrupt, and opportunistic persecution.

Considered the West’s first uniformed standing army, the extensive financial network of the Knights Templar once reached from London and Paris to the Nile and Euphrates Rivers, leading some chroniclers to label them history’s first multinational corporation. Though the order itself grew powerful and wealthy, its knights and sergeants always maintained their simple and austere lifestyle. Their bravery was legendary, their dedication absolute, and their attrition rate high; over two centuries at least 20,000 Knights Templar were killed, either on the battlefield or executed after being taken captive and refusing to renounce their faith.

After the loss of the Holy Land and the persecution of the Knights Templar, the Knights Hospitaller became the last of the old religious military orders still effectively resisting the rising tide of Muslim conquest. After they captured the Greek island of Rhodes, they built it into a strongly fortified naval base and for two centuries conducted vigorous maritime warfare that brought them prestige and riches. The Knights Hospitaller operated from Rhodes as a sovereign power, and later from Malta, which it administered as a vassal state under the Spanish viceroy of Sicily. In command of slave-rowed galleys, the Knights Hospitaller became master sea captains, and in 1522 their “holy piracy” provoked a determined attack by the 28-year-old Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I. The Knights Hospitaller lost Rhodes in 1522 to overwhelming Turkish numbers but not before their heroic, six-month defense so impressed Suleiman that he allowed the survivors to sail away under arms.

In 1530, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V, arranged for the Knights Hospitaller to occupy the Maltese archipelago—a barren home, but one in an unrivaled strategic position. Set in the narrows between Sicily and North Africa, Malta was a perfect base for denying Ottoman shipping access to the western Mediterranean waters that the sultan dreamed of dominating. The monk knights set about fortifying a superb natural harbor and renewed their aggressive campaign against Turkish warships and commerce. By 1564, the all-conquering Suleiman I—now called Suleiman the Magnificent—had come to regret the generosity of his youth when he spared the Knights Hospitaller defenders at Rhodes and was determined to crush this dangerous enemy once and for all. The six-month-long “Great Siege of Malta” followed.

Suleiman I was by then 70 years of age and could not lead his forces to Malta; he gave the command to Mustapha Pasha, a fiercely determined and brutal veteran of many campaigns, including Rhodes. Dragut Rais of Tripoli, one of the most successful corsairs of the period, supported Pasha. Dragut’s mission was to advise and mediate between Mustapha and the sultan’s admiral, Piali, whose fleet of 185 ships carried to Malta a force of 40,000, including 6,000 elite Janissaries and 100 cannon. Awaiting them on the island, which was well fortified with cannons, was Grand Master Jean Parisot de la Vallette. His knights and sergeants on Malta numbered 700 and were backed by 8,500 local Maltese troops and foreign volunteers, all concentrated in forts that ringed the vital harbor. After two grueling months of sea attacks by the Turks upon the harbor forts, massive artillery bombardments, mining, and massed ground assaults, the exhausted Turkish forces finally sailed away having suffered 20,000 casualties in an ugly battle of attrition. Suleiman I died in 1566, and in 1571 the Ottoman naval forces were soundly defeated at the Battle of Lepanto by the Holy League alliance of Venice, the papacy, Genoa, Spain, and the Knights Hospitaller.

After their bloody victory at the siege of Malta, the exhausted Knights Hospitaller became enfeebled. They survived, anachronistically, though in increasingly degenerate form, into the era of the French Revolution, finally surrendering the island of Malta to Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798. Even after Napoleon captured their island stronghold, representatives of the order continued to negotiate with the pope, the Russian tsar, and the monarchs of Europe in an attempt to return to their former prominence. It never happened, and none of the various organizations that through the years claimed, with varying degrees of plausibility, to be the order’s legitimate heir can be said to much resemble the order in its days of greatness.

I love reading your articles

Thank you