By Eric Niderost

Philadelphia is an historic city, rich in monuments dating from America’s colonial, Revolutionary, and early national periods. As every schoolchild knows, the Declaration of Independence was approved in Philadephia, and the city served as the nation’s capital from 1790 to 1800. Philadephia is also rich in military history, with nearby battlefields, fortifications, and militaria that span the whole gamut of the American experience, from the earliest colonial period to the end of the 20th century.

In fact, if you visit the city it’s possible to trace the entire history of human conflict throughout the ages. If you want to take such a tour chronologically, the best place to start is the Philadelphia Museum of Art. This is the home of one of the greatest collections of public art treasures in the nation. It’s truly a breathtaking assemblage, housed in a magnificent neoclassical building that is one of the city’s great icons.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s arms and armor collection is on the second floor of the sprawling complex. An ancient Greek Corinthian helmet shares honors with various types of Roman headgear, and nearby there are rows of matchlock and wheelock muskets. But the armor from the 15th, 16th, and early 17th centuries forms the backbone of the collection. An open-faced burgonet helmet is a typical example, its “cock’s comb” steel crest etched and gilded. Many of the pieces on display were made in Augsburg or Milan, where armorers were known for their skill and artistry. At the time of my visit, there was a three-quarter-length suit of cuirassier armor that was probably owned by King Gustavus Adolphus, the celebrated “Lion of the North,” during the Thirty Years War.

It’s ironic that Philadelphia should have military associations, because it was founded 300 years ago on the principles of peace, mutual respect, and toleration. William Penn founded the city in 1682, envisioning it as a “Holy Experiment” that would establish a colony dedicated to civic liberty and religious toleration. Penn was a Quaker, and pacifism was a basic Quaker belief, though individual Quakers sometimes fought as a matter of private conscience.

Any military tour of Philadelphia has to start at the Arch Street Friends Meeting House, the oldest Quaker place of worship in the city. It’s a plain yet beautiful building, with row after row of warm red brick crowned with an understated roofline. The Friends Meeting House (Society of Friends being the formal name for the Quaker faith) is an important first stop, because it amply illustrates the deep pacifist roots of Philadelphia that would be challenged during the American Revolution.

Inside the Meeting House, a series of dioramas illustrates scenes from William Penn’s life. One diorama shows Penn meeting with local Delaware Indians. According to tradition, a wampum belt was exchanged in token of peace and eternal friendship. Another scene shows Philadelphia about 1684, a place that Penn described as “Greene Country Towne.” Houses are starting to crowd the banks of the Delaware River, and broad avenues make straight furrows into the green belt of forest. The model notes that because Indian-white relations were cordial, there was no need to fortify Philadelphia. It must have seemed like a golden age—and like most golden ages, it was not destined to last.

Once you emerge from the Meeting House, you find yourself once again on Arch Street. If you go down Arch Street to the left, going west, you’ll find yourself at Christ Church Burial Ground. It’s most famous for being the last resting place of Benjamin Franklin; be sure to follow local tradition and toss a penny on the grave for good luck.

Among those buried here is Commodore William Bainbridge (1774-1833), whose ship the Philadelphia was captured by Barbary pirates. Bainbridge himself was held captive until ransomed by President Thomas Jefferson. Commodore Thomas Truxton, famed as the captain of the frigate USS Constellation during the so-called Quasi-War with the French in the 1790s, is also interred at Christ Church Burial Ground. The Burial Ground holds the remains of Colonel Benjamin Flower, head of the Artillery Artifices Regiment, a man whose chief responsibility was to repair army equipment during the Revolution. Colonel Edward Buncombe’s grave is also here. Wounded and taken prisoner at the Battle of Brandywine, he died in captivity. Buncombe County, NC, is named after him. It is said that the word “bunk,” meaning “nonsense,” is derived from his name.

After a visit to the Burial Ground, walk right, passing the Friends Meeting House as you do. Within a block of the Friends Meeting House you’ll arrive at the Betsy Ross home at 239 Arch Street.

Elizabeth Griscom, better known as Betsy Ross (1752-1836), typifies the triumphs and ordeals of American women on the “home front” during the Revolution. Betsy, a Quaker, was “read out” (expelled) from her church for marrying non-Quaker John Ross. Ross joined the Pennsylvania militia early in the war and was killed in a gunpowder explosion. Betsy married again, this time to sailor Joseph Ashburn, but once again tragedy struck. Ashburn’s ship was captured by the British and he died in prison. Eventually Betsy married John Claypoole, who had been a fellow prisoner in British captivity.

Betsy was a seamstress and upholsterer, and it is a fact that she sewed flags for the Pennsylvania state navy in 1777. She may or may not have sewed the first national “Stars and Stripes,” but in a way the matter is irrelevant. Beyond the flag controversy, a visit to her home points out how women performed other vital tasks during the long and bloody Revolution. In the “cartridge room,” you can view long strips of cloth and stocks of gunpowder on a table where Betsy and other women sewed cartridges. Soldiers loaded their muskets with such cartridges, which were often made of hand-sewn cloth. A man would rip open the fabric with his teeth, then pour the contents into the muzzle of his weapon.

The Atwater Kent Museum, located at 15 South 7th Street, offers a comprehensive chronicle of the city’s rich past. Do not be put off by the museum’s relatively modest dimensions; there are many treasures to view. “A Legacy for Philadelphia” is the Atwater Kent’s permanent exhibition, a showcase of 300 years that includes many memorable military objects. One glass case displays personal effects of General George Washington, including an epaulette from one of his uniforms and his camp knife and fork. A lock of Washington’s hair completes the ensemble.

At the time of my visit the 140th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg was fast approaching, which called for a series of special displays. General George Gordon Meade was a Philadelphian, so its citizens took special pride in doing him honor. Near the entrance a large portrait of the bewhiskered general was on show, together with his pocket watch and a presentation sword given to him for his victory at Gettysburg. Given to Meade in 1864, the sword and its scabbard are decorated in gold, silver, and silver gilt, set off with diamonds.

Mention also has to be made of Philly the Dog, mascot of Company A, 315th Infantry (“Philadelphia’s Own”), 79th Division, AEF (American Expeditionary Force). She was a mongrel who showed great bravery in the trenches during World War I. Philly received two honorary bronze stars and was wounded twice during the Meuse-Argonne campaign.

Once she was hit by shrapnel, and on another occasion suffered through a mustard gas attack. It was said that the German commander in her sector offered a bounty on her head because she was too noisy. It was a case of her bark being worse than her bite. After her passing in 1930, Philly was preserved and she greets visitors in her own special case of honor

The New Hall Military Museum presents the early years of America’s armed forces, roughly from 1775 to 1800. The building itself is a faithful replica of the one that stood on this site from 1791 to 1958; the original hall was the home of the U.S. War Department during the Washington administration. Once inside, the visitor is presented with a series of well-presented display cases that contain weapons, models, and various artifacts.

Most of the ground floor is devoted to the story of the U.S. Marine Corps, which had its birth at Tun’s Tavern in Philadelphia. A lively diorama shows a recruiting party marching through the cobblestoned streets, trailed by prospective marines and a gaggle of wide-eyed street urchins. Another case displays a variety of weaponry, including smoothbore muskets. One of the highlights of the ground floor is a scale model of the Raleigh, the first U.S. warship to fly the Stars and Stripes. The starboard side of the model is cut away to show the detailed interior, and tiny figures populating its decks bring the routine of an 18th-century sailor to vivid life.

The second floor houses a series of model soldiers that illustrate the development of the American fighting man from Jamestown through the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1795. Of particular interest is a flag given to General Philip Schuyler on his retirement. Dating from the 1780s—though its authenticity is disputed—the flag is likely one of the oldest American banners in existence.

It’s about time to take an excursion outside the city limits, but first visit the Civil War Library and Museum at 1805 Pine Street, in the city’s Rittenhouse Square District. There are three floors of Civil War artifacts on display, too numerous to mention in a short essay. Although little known by the general public, the Civil War Library and Museum is a treasure of rare and fascinating objects connected to America’s bloodiest conflict. For anyone interested in the Civil War, the museum is truly a must-see.

President Abraham Lincoln, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, and Philadelphian Maj. Gen. George Gordon Meade are spotlighted in a series of displays. Lincoln mementos include a lock of his hair and numerous art representations. Ulysses S. Grant’s relics include the original surrender document for Fort Donelson, a frock coat, a shoulder strap from a uniform worn by Grant during the siege of Vicksburg, and his field glasses.

In 1777 Philadelphia was the capital of the fledgling nation, which made it a major British military objective. The Philadelphia campaign lasted several months, a game of sanguinary chess that culminated in a series of hard-fought clashes between the British and Washington’s army. For convenience, the sites should be visited in terms of location, and not in chronological order. Fort Mifflin, a fascinating place that barely merits a casual mention in most guidebooks, is the nearest.

Fort Mifflin on the Delaware was one of the forts that guarded the river approaches to the city. Today, the area is literally a backwater where surrounding marshlands are home to a variety of wildlife. In 1777, the fort was in the river, located on Mud Island. The site’s only negative aspect is its close proximity to Philadelphia International Airport. During one recent visit, some commercial jets flew so low they looked as if they were trying to land on the parade ground.

But such modern nuisances are quickly forgotten, because Fort Mifflin does cast a spell. On November 10, 1777, the British attempted to force a passage up the Delaware by subjecting the fort to the heaviest bombardment of the Revolution. It is estimated that an average of a thousand cannonballs slammed into Mifflin every 20 minutes. The garrison never surrendered, but nonetheless was forced to abandon the fort after holding out for six days.

Fort Mifflin was a total wreck and was largely rebuilt in the 1790s. On the east and south walls are gray-colored fragments of dressed stone, the only remnants of the original 1777 fort that survived the terrible siege. Most of the stronghold as we see it today dates from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Visitors can tour Mifflin in a step-by-step fashion, and there’s much to see, including soldiers’ barracks and officers’ quarters, the latter furnished to represent the War of 1812 period.

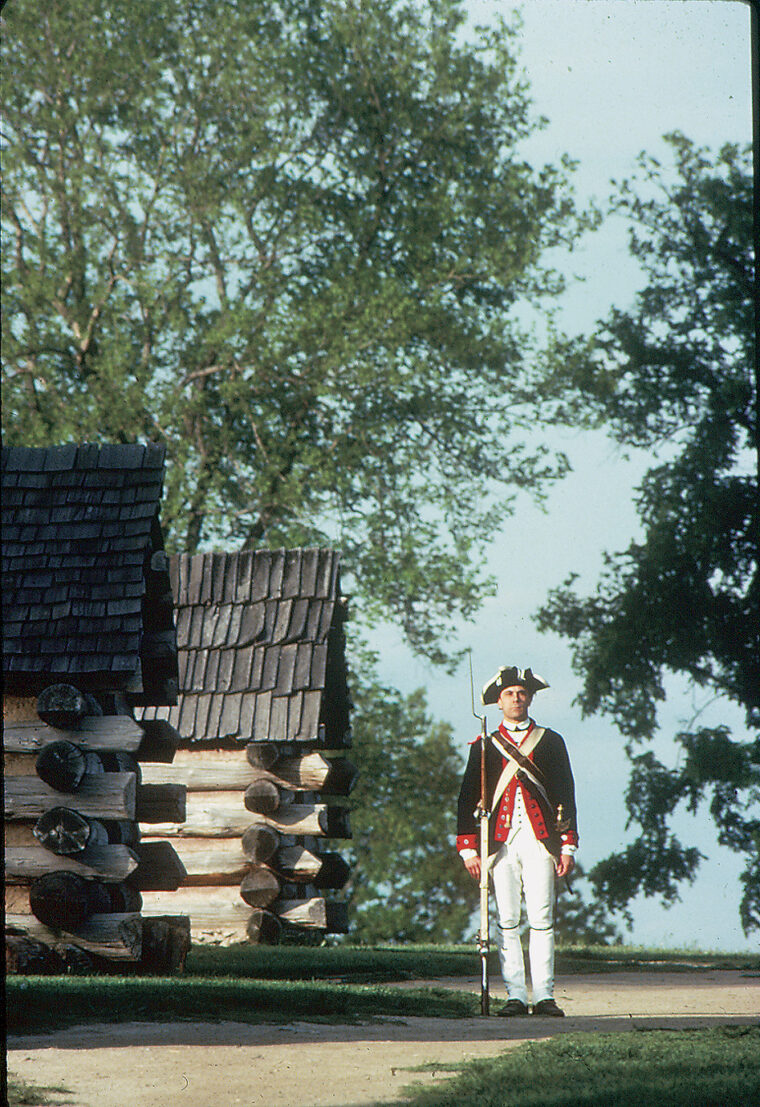

I was accompanied by Bill Ochester, a costumed guide who is also a reenactor with the 4th Continental Light Dragoons. Ochester pointed out that “reenactor events are periodically staged not only at Fort Mifflin, but also at the various battlefields in the area. In the summer of 2003, for example, there was a march out of Valley Forge that recreated when the Continental Army finally left winter quarters in 1778.”

The casemates of the Northeast Bastion are designed to be soldiers’ barracks in times of siege. The visitor threads through dark passageways, essentially man-made caverns of red brick that also served as prisons for Confederates during the Civil War. Cold, dank, and wet, it is said that these casemates are haunted. Perhaps not, but the chill one gets from touring through these underground passageways isn’t entirely caused by the temperature.

The next convenient stop is Brandywine Battlefield, perhaps a 40-minute drive from Mifflin. Brandywine was a major setback for the Americans in their attempt to defend Philadelphia from General William Howe’s British forces. The British found an undefended ford, then managed to surprise and flank Washington’s army. The Americans were forced to fall back, though their morale remained high. Howe marched on and eventually occupied Philadelphia. Highlights include a visitor center that has many objects associated with the battle and interesting related militaria. One particularly striking relic is a rare British grenadier bearskin cap, of a style first introduced in 1768. Guided tours regularly depart from the center to visit Washington’s headquarters and the old farm where the Marquis de Lafayette stayed.

Cliveden of the National Trust is a particular favorite of mine. During the Battle of Germantown, fought on October 4, 1777, a group of British soldiers took refuge in what was then called Chew House. Also called Cliveden, this is a beautiful example of colonial Georgian architecture that was built by Judge Benjamin Chew in the 1760s as a summer house. American attempts to take the mansion led to a protracted and bloody struggle, the British successfully repulsing all attacks. The Continental Army’s obsession with Cliveden turned the Battle of Germantown from a near-victory into a marginal defeat.

The mansion is unique and not to be missed. The rooms are elegant, well proportioned, and filled with period furniture. But the knowledge that men literally fought and died here gives Cliveden added poignancy, especially when you come across house battle scars. In one room, for example, there is an original bullet hole in one wall.

Valley Forge National Historical Park, a sprawling, 3,600-acre expanse of green pastures and rolling hills, is also not to be missed. The visitors center is the best place to start, with a good orientation film, brochures, and a fascinating exhibit that includes General Washington’s “Marquee,” a rare surviving example of an 18th-century tent. There are interesting memorials, historic buildings, and reconstructed soldiers’ camps that evoke those terrible “times that try men’s souls.”

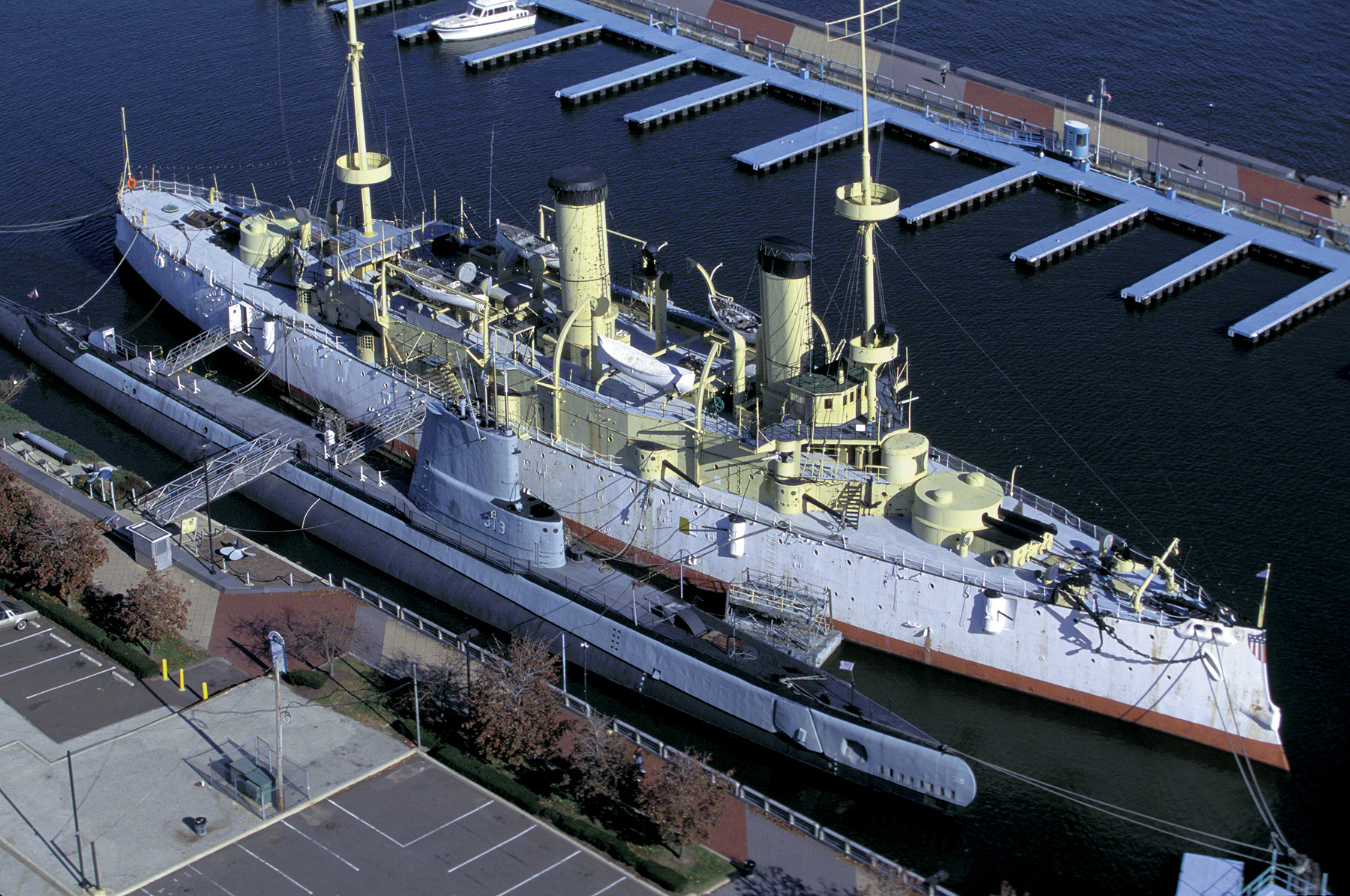

Most people associate Philadelphia with the Revolution, but there are interesting sights to see from later periods as well. The Independence Seaport Museum celebrates Philadelphia’s maritime history, which also resonates with military associations. Located at Penn’s Landing at Walnut Street, the Seaport Museum vividly demonstrates how Philadelphia’s shipyards turned out vessels that provided the backbone of the U.S. Navy. Uniforms, ship models, and dioramas detail this vital service in absorbing detail.

The USS Olympia, moored a short distance from the museum, is the only survivor from the Spanish American War. It was the flagship of Commodore George Dewey during the Battle of Manila Bay. The cruiser is moored in tandem with USS Becuna, a World War II submarine that is also open to the public.

Commissioned in 1895, the cruiser Olympia was one of the first all-steel ships in the U.S. Navy. A transitional vessel, it is recognizably modern yet has touches that are reminiscent of the days of sailing vessels. The senior officer’s quarters, for example, are sheathed in varnished chestnut, complete with sliding wooden doors that open into each stateroom.

A later stage in the evolution of warships can be seen from the decks of the Olympia. The battleship New Jersey (BB62) is just across the Delaware River in Camden, NJ. There is no need for a car; a scenic ferry link takes the visitor to within walking distance of the great ship; there is also a shuttle bus. Commissioned in 1943, the New Jersey first saw action in the Pacific in World War II. The ship’s distinguished history is too lengthy to detail here, but at one point she served as flagship for Adm. William “Bull” Halsey during the Battle of Leyte Gulf in 1944.

Docents are on hand to answer questions about the great battleship. Particularly impressive are the New Jersey’s nine 16-inch guns arrayed in triple turrets. Each gun barrel is about 30 feet long—impressive, but then the dimensions of the whole ship are worthy of awe. Battleship New Jersey boasts a length of 887 feet, 7 inches.

A small museum hosts a fascinating presentation called “Keepers of the Sea: International Battleship Development.” The exhibition traces the development of the modern battleship from 1905 to 1992 through a series of superbly detailed scale models. There’s a model of the New Jersey, of course, but also such historic vessels as the World War II battleships Bismarck, Yamato, and Prince of Wales.

A modernized New Jersey saw service as late as 1983, providing fire support for U.S. Marines in Lebanon. Decommissioned in 1991, the New Jersey brings a survey of military Philadelphia to the present.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments