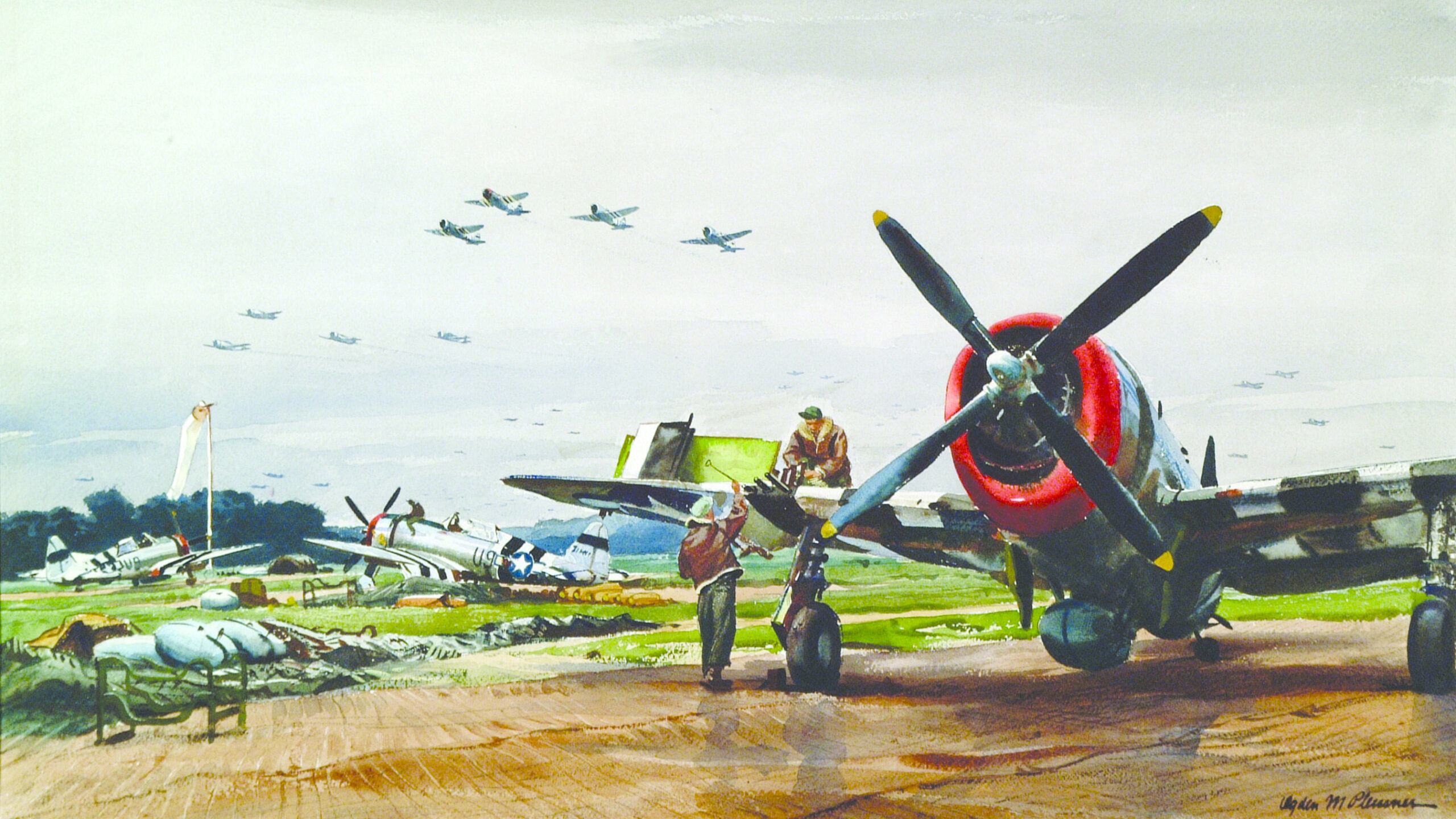

The nightmarish vision that the Japanese high command had hoped to forestall with its Special Attack Unit raids on American airbases in the Marianas did, with devastating effect, become reality in the spring of 1945. Waves of the gigantic Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers, based primarily on the islands of Guam and

Tinian, delivered cargoes of death and destruction on an unprecedented scale. With a range of 3,250 miles and a payload of 5,000 pounds of bombs, the massed four-engined bombers

executed some of the most horrific destruction in the history of warfare.

The principal architect of the American bomber offensive against the Japanese Home Islands was General Curtis E. LeMay, who directed the operations of XXI Bomber Command from the Marianas. A group commander in the Eighth Air Force when the war began, LeMay rose rapidly through the ranks during the conflict. He directed the 305th Bomb Group over Europe and developed the concept of tight formation flying in mutually supportive “boxes” for Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses in action over the Continent.

Transferring to the Pacific in July 1944, LeMay was promoted to major general and directed massive incendiary raids against more than 60 Japanese cities. Initially, high-altitude daylight raids met with only modest success, but a switch to low-level night attacks had telling results. LeMay was a staunch advocate of strategic bombing and continuously looked for ways to improve its effectivness.

The most memorable of a string of firebombing raids was delivered against Tokyo on the night of March 9-10, 1945. It was also the first test of LeMay’s new doctrine of low-level attack. Near midnight on that clear evening, 280 B-29s thundered across the skies above the capital and dropped more than 2,000 tons of incendiaries on an area a little larger than 12 square miles. Most of these bombs fell on the working-class suburbs of Koto and Shitamachi. The simple dwellings in these neighborhoods, constructed primarily of wood and rice paper, went up like torches.

Within half an hour the bombers were gone, but the agony of Tokyo was just beginning. Winds gusting up to 40 mph fanned the flames, creating oxygen-consuming firestorms and searing heat. Many people died of suffocation, while others were engulfed in the flames. Some sought a haven in the waters of the Sumida River and nearby canals.

As dawn began to break, the flames could be seen for 150 miles. The last fire was not extinguished until four days after the raid. While the exact number of casualties is unknown, estimates place it between 80,000 and 200,000. Roughly 16 square miles of Tokyo had been completely destroyed.

In the coming months, the B-29s laid waste to other Japanese cities that held targets of military value, including Kobe, Nagoya, and Osaka. On some days, as many as five different cities were targeted. During the month of July 1945, more than 150,000 tons of bombs were dropped, resulting in 500,000 dead and 13 million left homeless in more than 20 urban areas.

LeMay’s raids undoubtedly crippled the ability of the Japanese to continue to wage war. His focus was unrelenting and his men acknowledged this drive with the nicknames “Iron Ass” and “Iron Pants.” After the war, the general served as Deputy Chief of Air Staff for Research & Development and commanded U.S. Air Force operations in Europe during the Berlin Airlift of 1948.

In 1949, LeMay replaced General George C. Kenney as the head of Strategic Air Command. He held that post until 1957, then served as Vice Chief of Staff for the Air Force and subsequently as Chief of Staff. In 1968, he entertained a brief political career as the vice presidential running mate of former Alabama Governor George Wallace. Some believe LeMay is the basis for the character of General Jack D. Ripper in the movie Dr. Strangelove.

General Curtis LeMay died in 1990, but his legacy as an advocate of strategic bombing lives on in the modern U.S. Air Force. That philosophy was born in the skies over Europe and in the general’s mind it was proven against Imperial Japan.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments