by Jonathan North

Although the terrain around the Battle of Borodino presented the Russians with a number of good opportunities for a defensive battle, they further strengthened their positions with hastily constructed earthworks.

The first of these was the Schevardino Redoubt, positioned about a mile in front of the Russian main line. Although the exact purpose of the earthwork is unclear, it proved a difficult obstacle for the French to take. With earth packed to a height of four or five feet, and fronted with a steep-sided ditch, the redoubt was the scene of a fierce and prolonged struggle on the afternoon of September 5 as both sides clashed in a bloody encounter. Two days later, it served as the position for Napoleon Bonaparte’s headquarters during the battle proper.

Bagration “fleches”

More important were the Bagration “fleches.” These were hastily constructed by the inexperienced men of the Moscow militia on the 4th and 5th and were designed to strengthen the rather weak and exposed Russian left. There were three of these V-shaped, or chevron-shaped, earthworks, two side by side and one, much smaller, a hundred yards to the rear. The two larger earthworks were open to the rear to enable reserves to be fed in whenever desired and to make the positions more difficult for the enemy to defend should they be successful in their assaults.

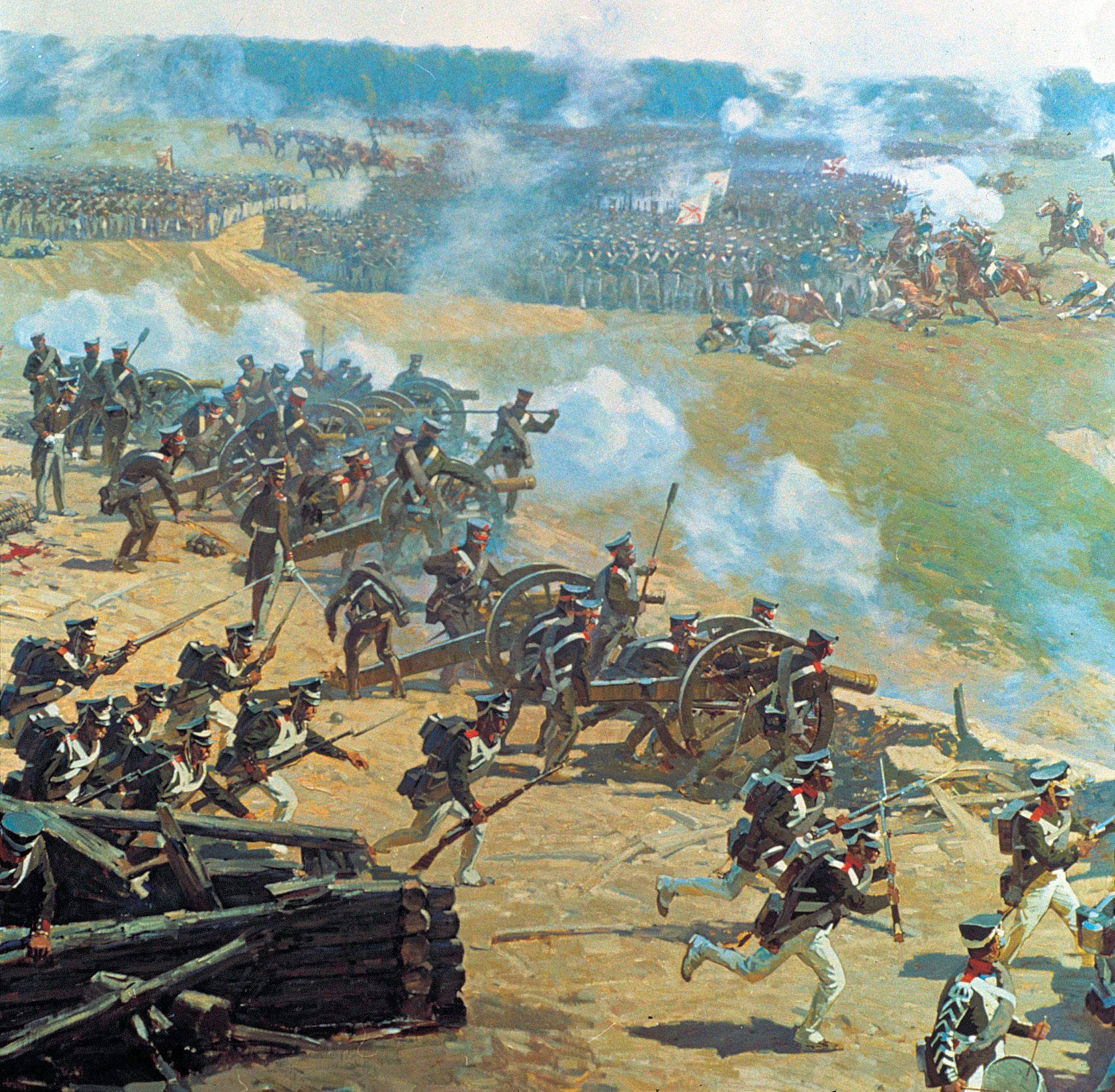

Each fleche was pierced to allow a 12-gun position battery to fire at the attackers. The works were constructed of sandy soil and supported by wood, although no gabions [baskets packed with earth] were available to add further support. They were built up to chest height and fronted with a shallow ditch. Each fleche could hold and offer partial protection to a battalion of Russian infantry. The fleches were largely destroyed in the fighting, being obliterated by artillery bombardment and charge and countercharge of infantry and cavalry, but exact replicas were constructed in the 19th century and these can still be seen today.

Rajevsky Batteries, Redoubts and Wolf-Pits

More significant, in terms of structure and strength, was the Great Redoubt or Rajevsky Battery. This famous position was built by militia and men of Rajevsky’s division, desperately short of pickaxes and spades, under supervision of Russian engineer officers, and was intended to hold a battery of 18 guns from the 26th Artillery Brigade (12 guns from the 26th Battery Company and 6 from the 47th Light Company).

The earthworks were again V-shaped but they were not open to the rear. Instead, a low wooden wall ran behind the V and extended beyond it on either side. The earthworks had been thrown up quickly on September 6, work continuing during the night, and were not finished by the time the battle began in earnest on the 7th. Even so, considering its physical position, the Redoubt was well placed and presented the attackers with a formidable obstacle.

To further augment that strength the Russians dug wolf-pits in front of the position. These were designed to act as an obstacle for French cavalry but also, of course, proved fatal to a number of French infantrymen throughout the fighting. Ironically, Napoleon’s cavalry did play a crucial part in the taking of the Battery—by skirting around its flanks and attacking the position from the rear.

One wonders, having much more time for construction, how strong were the redoubts and fieldworks constructed by the Austrians prior to the battle of Wagram in 1809?