By John Walker

The South Vietnamese rangers huddled in their trenches and bunkers at landing zone Ranger North throughout the day of February 19, 1971, as mortar shells crashed inside the perimeter. The deadly shells sent geysers of dirt toward the low-hanging, gray sky over eastern Laos. To counter the encroaching North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars, U.S. Cobra gunships and F-4 Phantoms took turns rolling in to blast enemy positions. The 5,000 enemy soldiers laying siege to the hilltop base outnumbered the rangers 10 to 1. By the 11th day of operation Lam Son 719, U.S. air support was the only thing that separated life from death for the beleaguered troops of the 39th Ranger Battalion at Ranger North.

At dusk a regiment of the NVA 308th Division began a steady mortar bombardment of the base. Fanatical NVA regulars, who were supported by Soviet-built PT-76 and T-54 tanks, charged the perimeter repeatedly and eventually broke through. Hand-to-hand fighting broke out in a number of places. The rangers suffered from a severe shortage of antitank weapons and were not experienced with those they had. The air swarmed with U.S. supply and medevac helicopters, as well as aerial rocket artillery. The ground around the hilltop base lit up periodically with flames from napalm canisters dropped by Phantoms that roared down on the jungle. UH-1 “Huey” helicopters zipped onto the smoke-shrouded hilltop bearing supplies and, when possible, removed wounded while the Cobras pumped rockets at NVA caught in the open. For their part, NVA soldiers desperately tried to knock the Hueys from the sky with their AK-47s, rocket-propelled grenades, and heavy antiaircraft machine guns.

Dawn on February 20 revealed the contorted bodies of hundreds of dead NVA both on the hillsides and within the perimeter. Crews of U.S. helicopters alighting on the hilltop did their best to keep back panicked rangers who tried to grab their skids, threatening to overload their fragile airships. In the fighting over a three-day period, the force of 500 rangers on the hilltop base had dwindled to 323.

It was clear that afternoon that the rangers could not hold off the NVA. It also was clear that U.S. air units could not evacuate their allies under such intense fire. With no other option, the ranger commander ordered his men to fight their way out toward Ranger South just over three miles away. What followed was a running battle in the frantic retreat to Ranger South. Only 109 able-bodied survivors and 92 wounded made it to safety by nightfall. As for the NVA casualties, they lost at least 600 men and perhaps substantially more. It was a scenario repeated at a number of other firebases established to support the South Vietnamese raid to temporarily sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail and disrupt NVA offensive operations.

By 1970, with the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Southeast Asia finally under way, it was apparent the long-standing American policy of supposedly respecting the neutrality of the bordering Indochinese countries of Laos and Cambodia while fighting a localized war of attrition inside South Vietnam had been a profound strategic blunder. As early as 1960, large portions of Laos and Cambodia had been, in effect, invaded and occupied by North Vietnamese ground forces, who established the Ho Chi Minh Trail as their principal route for funneling communist troops, weapons, and supplies into South Vietnam. The restriction confining the ground war to South Vietnam did not apply to American aerial bombing; indeed, North Vietnam and the Ho Chi Minh Trail were bombed extensively for years, yet the bombing campaign was not decisive in determining the war’s outcome. Since 1966, more than 630,000 North Vietnamese soldiers, 100,000 tons of foodstuffs, 400,000 weapons, and 50,000 tons of ammunition had traveled south through the maze of gravel and dirt roads, footpaths, and river transportation systems that crisscrossed southeastern Laos and linked up with a similar logistical system in neighboring Cambodia known as the Sihanouk Trail.

Following Prime Minister Lon Nol’s overthrow of Cambodia’s Prince Norodom Sihanouk on March 18, 1970, though, the new pro-American Lon Nol regime denied the use of the port of Sihanoukville to communist shipping. This was an enormous strategic blow to North Vietnam, since 80 percent of all military supplies that supported its effort in the far south had moved through this port. Lon Nol also ordered the NVA and Viet Cong (VC) out of Cambodia. The VC were South Vietnamese communist insurgents, fighting mostly as irregulars under the banner of the National Liberation Front and under North Vietnamese control.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail began in North Vietnam and ran through Laos into northern Cambodia, with spurs branching into each of almost two dozen bases along the border. The eastern sector of the Laotian panhandle had long been home to many vital logistical installations and base areas. The main hub of the entire complex in this sector of the trail was Base Area 604, sited in and around the district town of Tchepone, Laos, roughly 24 miles west of the Laos-Vietnam border. After the Cambodian government’s closure of the port of Sihanoukville, Base Area 604 became even more vital to the North Vietnamese war effort.

The next largest supply base was Base Area 611 in Muong Nong Province, south and east on Route 914 from Tchepone. It was much closer to the Vietnamese border and was located on the western fringe of the A Shau Valley where it entered Laos. In late 1970, expecting an attack into Laos, the North Vietnamese created a field command—the B-70 Corps commanded by General Le Trong Tan, its nucleus the 304th, 308th, and 320th Divisions—specifically to fight in Laos and had substantial capacity to reinforce their original dispositions.

A further blow to the communist logistical system came in spring 1970 when U.S. and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces crossed the border into Cambodia in strength and attacked NVA/VC base areas during the controversial Cambodian incursion. That allied offensive into Cambodia is sometimes portrayed as a strategic failure, but it was not. Though hugely unpopular in the United States, the operation was in fact the key event needed to sever the enemy’s lines of communication and logistics in Cambodia, ease the American withdrawal program from the theater, and showcase the success of the Vietnamization program while also boosting the morale of ARVN soldiers.

The Cambodian incursion was a success by any measure. The allies seized enough weapons and ammunition to arm 55 battalions of an enemy main-force unit, killed 11,363 enemy soldiers, and captured more than 2,000 soldiers. But the allies failed to locate the military and political headquarters of the NVA/VC forces, and they also failed to encounter large enemy concentrations because the enemy had withdrawn deeper into Cambodia. Military activity increased after the operation in both northern Cambodia and southern Laos as the North Vietnamese attempted to establish new infiltration routes and base areas.

After the near destruction of the enemy’s logistical system in Cambodia, U.S. headquarters in Saigon determined the time was favorable for a similar campaign into the Kingdom of Laos (the coalition government of Laos had come to an agreement with influential North Vietnamese sympathizers that prevented them from objecting to communist operations inside their country). If such an operation were to be carried out, it would have to be done quickly while American military assets were still available in South Vietnam. Such an operation might potentially create severe supply shortages that would be felt by NVA/VC forces for at least one year, and possibly two, thus giving the United States and its ally a respite from possible enemy offensives in the vital northern provinces for a year or more.

The allies discovered signs of increased NVA logistical activity in southeastern Laos, activity that heralded just such an offensive. Communist offensives usually took place near the conclusion of the Laotian dry season (from October through March) after supplies had been pushed through the system by logistics units. One U.S. intelligence report estimated that 90 percent of NVA matériel coming down the trail at that time was being funneled into the three northernmost provinces of South Vietnam in preparation for offensive action. This buildup was alarming to both Washington and the American command in Saigon and prompted the perceived necessity for a preemptive attack to disrupt any attempted communist offensives.

On December 8, 1970, in response to a request from the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, a highly secret meeting was held at Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) headquarters in Saigon to discuss a possible ARVN attack into southeastern Laos, across the border from I Corps in northern South Vietnam. The group’s findings were sent to the Joint Chiefs in Washington. By mid-December U.S. President Richard Nixon had become intrigued by the idea of offensive actions in Laos and had begun efforts to convince General Creighton Abrams, supreme MACV commander in South Vietnam, and members of his own cabinet of the efficacy of such an attack. Nixon was well aware that another border crossing would severely enflame public opinion, but he and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger were overly optimistic and believed a clearcut ARVN victory would trump any political consequences. As promised, Nixon had begun the systematic withdrawal of American forces from South Vietnam, lowering U.S. troop strength there to around 157,000 men by early 1971. (Nixon assumed office in January 1969 and troop withdrawals began in the summer of that year.)

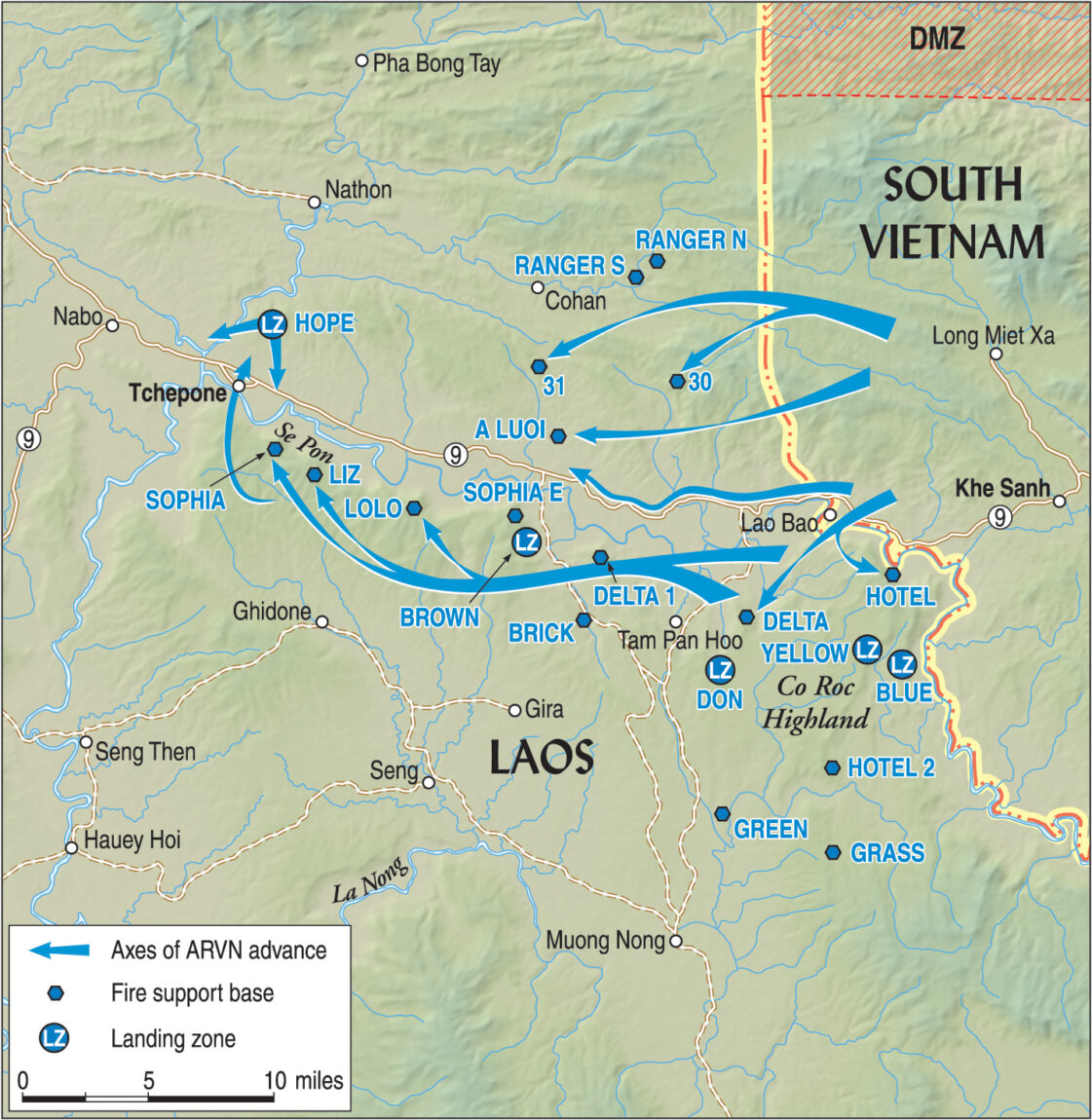

On January 7, 1971, MACV was authorized to begin detailed, highly secret planning for an attack against Base Areas 604 and 611 in lower Laos. On the American side, the task was assigned to Lt. Gen. James Sutherland, commander of the U.S. XXIV Corps, who was given only nine days to submit it to MACV for approval. The operation would eventually consist of four distinct phases. During the first phase, the U.S. 45th Engineering Group would seize, rebuild, and secure Route 9, the main road leading east to and into Laos; the 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) would reoccupy the abandoned Khe Sanh Combat Base, which would become the logistical hub and airhead of the ARVN part of the operation; and, in an operation dubbed Dewey Canyon II, the 101st Airborne Division would conduct diversionary operations into the A Shau Valley near the Cambodian border, long a communist stronghold.

The second phase entailed a three-pronged ARVN armored/infantry attack west along Route 9 across the border into Laos, pushing for the town of Tchepone, the perceived nexus of Base Area 604. Total American air, artillery, and logistical support—but no U.S. advisers or ground troops, who were now prohibited by law from entering Laos—would support the South Vietnamese incursion. The column’s advance along Route 9 would be protected by a series of leapfrogging, heliborne infantry assaults on both sides of the highway, where rapidly erected ARVN fire bases and landings zones would cover the northern and southern flanks of the road-bound main column. The operation’s third phase called for search and destroy missions within Base Area 604 and, it was hoped, against Base Area 611 if conditions permitted. Then, ARVN forces would retire, either going back along Route 9 or southeast to Base Area 611, through the part of the A Shau Valley that jutted into Cambodia, and across the border.

Because of the South Vietnamese military’s notorious carelessness with regard to security precautions and the uncanny ability of communist agents to uncover detailed information, the planning phase lasted only a few weeks, divided between the American and South Vietnamese high commands. At the operational levels, it was limited to the intelligence and operational staffs of the ARVN I Corps, whose commander, Lt. Gen. Hoang Xuan Lam, would command the operation, and Sutherland’s XXIV Corps. Lam was briefed by MACV and the South Vietnamese Joint Chiefs of Staff in Saigon just days before the operation’s start. At this point, his operational area was restricted to a corridor no wider than 15 miles on both sides of Route 9 and a penetration no deeper than Tchepone.

In the highly politicized South Vietnamese military’s command structure, where the support of key political figures was of paramount importance in promotion to and retention of command positions, the issues of command, control, and coordination proved problematic. Lt. Gen. Le Nguyen Khang, South Vietnamese Marine Corps commander and protégé of Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, whose Marines were scheduled to participate in the incursion, outranked Lam, who was supported by President Nguyen Van Thieu. The same situation applied to Lt. Gen. Du Quoc Dong, commander of ARVN airborne forces also scheduled to participate. Rather than take orders from Lam, both commanders remained in Saigon and delegated their command authority to subordinate officers, which certainly did not bode well for the success of the incursion. The operation was dubbed Lam Son 719 after the village of Lam Son, birthplace of the legendary Vietnamese patriot Le Loi, who defeated an invading Chinese army in 1427. The numerical designation came from the year 1971, and the main axis of the attack, Route 9.

The attempt at secrecy jeopardized logistical and communications preparations that required lengthy lead time, and a combined tactical command post was not established until the operation was well under way. Most units did not learn about their planned participation until January 17. The Airborne Division received no detailed plans until February 2, less than a week before the campaign was to begin. Some of the best and most experienced units, the paratroopers and Marines, had always deployed in their own areas of operation as separate battalions and brigades and had no experience cooperating in combined unit operations. The U.S. 101st Airborne Division’s assistant commander later said, “Planning was rushed, handicapped by security restrictions, and conducted separately and in isolation by the Vietnamese and the Americans.” U.S. helicopters, artillery, and supplies were moved at the last minute into the Khe Sanh Combat Base, where an entirely new airstrip had to be constructed. Because there were few possible locations for attacks into Laos, and the North Vietnamese were already expecting some kind of activity in the area, any attempt at secrecy failed.

On their own for the first time without American advisers, South Vietnamese generals faced their biggest test yet. Lam Son 719 was ARVN’s largest, most complex, and most critical operation of the war. The lack of time for adequate planning and preparation, as well as the absence of any real discussion of military realities and the true capabilities of the ARVN, could potentially prove decisive. Nixon gave his final approval for the mission on January 29 and the following day Operation Dewey Canyon II began (it was hoped the 101st Airborne’s feints into the A Shau Valley might draw NVA attention away from what was going on at Khe Sanh). On the morning of January 30, as well, armored and engineer elements of 1st Brigade, U.S. 5th Infantry Division (Mechanized) headed west on Route 9 while the brigade’s infantry units were helilifted directly into Khe Sanh. The government of Laos was not notified in advance of the intended operation; Prime Minister Souvanna Phouma learned of the invasion of his country only after it was under way (the same had been true of the Cambodian incursion a year earlier).

Tactical airstrikes set to precede the incursion to suppress suspected antiaircraft positions had to be suspended for two days due to poor weather. After a massive preliminary artillery bombardment and 11 B-52 Stratofortress missions, the incursion began on February 8, 1971. Spearheaded by M-41 light tanks and M-113 armored personnel carriers, a 4,000-man ARVN armor and infantry task force, comprising the 1st Armored Brigade, the 1st and 8th Airborne Battalions, and the 11th and 17th Cavalry Regiments, crossed the border and advanced six miles westward unopposed along Route 9.

To cover the northern flank, the 39th Ranger Battalion was helilifted into Ranger North while the 21st Ranger Battalion air assaulted into Ranger South. Meanwhile, the 2nd Airborne Battalion established FSB 30 while the 3rd Airborne Brigade Headquarters and 3rd Airborne Battalion moved into FSB 31 (both north of the road as well). These outposts were to serve as tripwires for any communist advance into the zone of the ARVN incursion. South of Route 9, units of the crack 1st ARVN Infantry Division simultaneously combat assaulted into landing zones Blue, White, Don, and Brown, and FSBs Hotel, Hotel 2, Delta, and Delta 1, to establish the southern flank of the advance.

Lam Son 719 was under way. Although intelligence reports indicated the terrain along Route 9 in Laos was favorable for armored vehicles, in reality it was a neglected, 40-year-old, unevenly surfaced, single-lane dirt road with high shoulders on both sides that left no room for maneuver. The entire area was filled with huge bomb craters, undetected earlier by aerial reconnaissance because of dense grass and bamboo. Tracked vehicles, jeeps, and trucks were, therefore, restricted almost entirely to the road, which threw the burden of reinforcement and resupply onto U.S. aviation assets. American helicopter units thus became the essential mode of logistical support, a role made increasingly more dangerous by regular low cloud cover and unremitting antiaircraft fire.

The mission called for the central column to advance down the valley of the Se Pone River, a relatively flat area of brush interspersed with huge swaths of jungle, dominated by heights to the north and the river and more mountains to the south. From the second day forward, the column was exposed to fire from the heights as NVA gunners fired down from preregistered machine-gun and mortar positions. U.S. Army helicopter pilots flying gunship and resupply missions—and later when they attempted to rescue ARVN troops from besieged hilltop firebases—encountered savage, accurate antiaircraft fire. The NVA’s favorite antiaircraft weapon, among others, was the 12.7mm Soviet-made heavy antiaircraft machine gun, which fired 600 rounds per minute and could damage an aircraft at elevations up to 3,000 feet. The highly accurate weapon helped bring down of hundreds of American helicopters during the war.

The ARVN column secured Route 9 as far as the village of Ban Dong, known to the Americans as A Luoi, 12 miles inside Laos approximately halfway to Tchepone. By February 11, A Luoi had become ARVN’s central firebase and command center for the operation. The plan now called for a quick ground thrust to secure Tchepone, but South Vietnamese forces found themselves stalled at A Luoi while awaiting overdue orders from Lam to continue. Abrams and Sutherland flew to Lam’s forward command post at Dong Ha in a futile effort to speed up the timetable. After the commanders’ meeting, Lam decided to first extend the 1st ARVN Infantry Division’s line of outposts south of Route 9 farther westward before the projected advance, which took another five days.

Hanoi’s response to the incursion was gradual because North Vietnamese leaders believed their country was in danger of being attacked, either by an allied ground assault north across the Demilitarized Zone or a U.S. Marine amphibious landing off their eastern coast. When Hanoi’s leaders realized they were not going to be invaded, units of the B-70 Corps were ordered toward the Route 9 front. The 2nd NVA Division moved up from south of Tchepone and moved east to help meet the ARVN threat, while other units marched to the area from the A Shau Valley. By early March, the North Vietnamese had massed some 36,000 soldiers in the area, giving them a numerical superiority of two to one over ARVN’s 17,000 men. The NVA committed elements of five infantry divisions (2nd, 304th, 308th, 320th, 324B) along with all their armor and artillery support, all of the logistical units operating in the area, an engineer regiment, six well-camouflaged antiaircraft battalions, and six sapper battalions.

The NVA had massed its combat power for a larger purpose than defending their critical supply route. They were determined to seize an opportunity to fight a decisive battle on advantageous terms, destroy a large ARVN force, and thoroughly discredit and disrupt Vietnamization. The NVA opted to isolate the northern ARVN bases first, pounding those outposts with round-the-clock mortar, artillery, and rocket fire, as well as fierce antiaircraft fire against supporting air units. Although ARVN firebases were equipped with artillery, their guns were outranged by the enemy’s Soviet-supplied 130mm and 152mm pieces, which simply stood off and pounded ARVN positions at will. Massed ground attacks backed by artillery and armor would then finish the job.

While the NVA assault on Ranger North raged, Thieu visited I Corps headquarters and was notified of the attacks on the ranger bases and the overall major increase in enemy activity that made an advance on Tchepone questionable. Thieu advised Lam to postpone the main column’s advance on Tchepone and instead have the 1st ARVN Division, south of Route 9, begin a push southwest in the direction of Tchepone.

The North Vietnamese next shifted their attention to Ranger South. The outpost’s 400 ARVN troops and the survivors from Ranger North fought bravely for two days to hold the post, after which Lam ordered them to fight their way three miles southeast to FSB 30. Another casualty of the campaign, though an indirect one, was South Vietnamese General Do Cao Tri, III Corps commander and ARVN hero of the Cambodian fighting a year earlier. Ordered by Thieu to take over for the overmatched Lam, Tri died in a helicopter crash on February 23 while en route to his new command. That same day, FSB Hotel 2, south of Route 9, came under an intense infantry attack and was evacuated the next day.

FSB 31 was the next ARVN position to come under heavy enemy pressure. Dong, the Airborne Division commander, had opposed deploying his elite paratroopers in static defensive positions because he believed it stifled their usual aggressiveness. When vicious NVA antiaircraft fire made resupply and reinforcement of FSB 31 almost impossible, Dong ordered elements of the 17th Armored Squadron to advance north from A Luoi to reinforce the base. The armored force never arrived, however, due to conflicting orders from Lam and Dong, who halted the armored advance a few miles south of FSB 31. On February 25, the NVA pounded the base with artillery fire and then launched a conventional ground attack. Smoke, dust, and haze at first precluded observation by an American forward air control (FAC) aircraft, which was flying above 4,000 feet to avoid antiaircraft fire. When a Phantom was shot down not far away, the FAC left the area to direct a rescue operation, leaving the defenders with no one to direct fire support. NVA troops and tanks overran the base, capturing 3rd ARVN Brigade’s commander in the process, while losing an estimated 250 men killed and 11 tanks lost. The ARVN paratroopers suffered 155 killed and more than 100 captured.

A bit farther east, FSB 30 lasted almost another week. Although the steepness of the hill on which the base was situated precluded armor attacks, NVA artillery barrages were extremely effective, and by March 3 all of the base’s 11 howitzers had been put out of action. ARVN armor and infantry from the 17th Cavalry moved north in a relief attempt and within days North and South Vietnamese tanks fought the first armored battles of the war. In the five days between February 25, the day FSB 31 fell, and March 1, three major engagements took place. With the help of U.S. airstrikes, the ARVN destroyed 17 PT-76 Soviet-built tanks and six T-54s at a loss of three of its five M-41 tanks and 25 M-113 armored personnel carriers. On March 3 the ARVN relief column encountered an NVA battalion without supporting armor, and with the assistance of B-52 strikes killed 400 North Vietnamese soldiers.

During each of the enemy’s attacks upon FSB 30 and the ARVN relief column, communist ground forces suffered heavy losses from B-52 and tactical airstrikes, armed helicopter attacks, and various forms of ground fire. In each instance, however, the NVA attacks were pressed home with a competence and determination that both impressed and profoundly shocked those that observed them. The NVA lost more than 1,130 soldiers killed in the battle.

With their main column stalled at A Luoi and the rangers and paratroopers fighting for their lives, Thieu and Lam now decided to launch an airmobile assault upon Tchepone itself. The Tchepone area was sparsely populated; most of the nearby villages and towns had been evacuated or largely destroyed by the war. There was not much of military importance within the deserted town of Tchepone; most of the NVA’s supplies and other war matériel had been moved to caches in nearby forests and mountains west and east of the town proper. A particularly large, lightly defended cache was located just west of Tchepone, but the ARVN was unable to reach it. But because the Tchepone road junction was near the center of NVA logistical activity in the vital Laotian panhandle area, the ghost town had become a political and psychological symbol of great importance, more than an object of military value.

American commanders and news media had focused on Tchepone as Lam Son 719’s main objective. If ARVN forces could occupy at least part of the city, therefore, Thieu would have a political excuse for declaring a victory, of sorts, and withdrawing his forces to South Vietnam, as well as gaining political capital for the upcoming fall elections and saving his elite units from destruction. Thieu’s orders called for an assault on Tchepone, not with the main armored column, but with elements of the crack 1st Infantry Division now deployed south of Route 9. The occupation of vacated firebases south of the road would be taken over by South Vietnamese Marine Corps units stationed back at Khe Sanh as the operational reserve.

To Thieu’s credit, with the main ARVN column still miles away at A Luoi, the air assault on Tchepone caught the North Vietnamese off guard. It began on March 3 when one battalion from 1st Division was helilifted into two firebases, Sophia and Lolo, and landing zone Liz, all south of Route 9. Eleven helicopters were shot down and another 44 damaged. Three days later, in the biggest helicopter assault of the war, 276 Hueys, protected by Cobra gunships and fighter aircraft, lifted two more battalions into landing zone Hope, 21/2 miles north of Tchepone. Only one helicopter was lost to antiaircraft fire and an entire regiment of the ARVN’s best soldiers, several thousand men, was now on the ground in and around Tchepone. The NVA had not anticipated the move and could not react quickly enough to stop it; they did, however, hit the four bases, notably Lolo and Hope, with long-range artillery barrages.

Not far from Tchepone were several large storage areas still stocked with weapons, ammunition, medical supplies, rations, and equipment. Other areas nearby were used for troop replacement and training. ARVN soldiers scoured Tchepone and the surrounding area for almost a week, methodically destroying everything in sight or using artillery, tactical air, or gunships to destroy depot areas. Several thousand NVA soldiers (ARVN claimed 5,000), mostly rear area troops or troops in rest areas, were killed and another 69 captured. Almost 4,000 captured enemy weapons were airlifted out and returned to South Vietnam and several thousand tons of enemy equipment destroyed.

With their goal in Laos seemingly achieved and with enemy resistance near Tchepone mounting, Thieu and Lam now cut Lam Son 719 short and ordered the withdrawal of all South Vietnamese forces, to begin on March 16. A frustrated Abrams implored Thieu to reinforce his troops in Laos (with the 2nd ARVN Infantry Division) and continue the offensive until the beginning of the rainy season. Abrams believed the ARVN, if properly reinforced, could turn the tide, inflict a crippling defeat on the enemy, and seriously damage, if not sever, the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Thieu waited too long, however, as the battle shifted to Hanoi’s advantage. Antiaircraft fire remained devastating and the communists had no trouble reinforcing or resupplying their troops in the battle area, which they knew well. When it became evident that ARVN had begun a withdrawal, the NVA mounted efforts to destroy South Vietnam’s forces before they could reach the border. Antiaircraft fire was increased to halt or slow helicopter resupply and evacuation efforts, undermanned ARVN firebases and landing zones were attacked, and ARVN ground forces had to run a deadly gauntlet of ambushes along Route 9.

Only a well-disciplined and coordinated army can execute an orderly withdrawal in the face of a determined enemy, and South Vietnamese forces at this point were neither. The retreat quickly turned into a rout; one by one, isolated fire support bases and landing zones were abandoned or overrun by the NVA. On March 21, South Vietnamese Marines at FSB Delta, south of A Luoi and Route 9, came under intense ground and artillery attacks. During an attempted extraction of the Marines, seven helicopters were shot down and another 50 damaged, ending the evacuation attempt. The Marines finally broke out of the encirclement with heavy losses and fought their way to FSB Hotel, which was then hastily abandoned as well. During the extraction of the 2nd ARVN Regiment and Marines from FSB Hotel, 28 of 40 helicopters participating were damaged. The armored task force fared little better, losing 60 percent of its tanks and half its armored personnel carriers to fuel shortages, breakdowns, or deadly NVA ambushes. Some 54 105mm and 28 155mm howitzers were abandoned and had to be destroyed by U.S. aircraft to prevent their capture and reuse by the enemy.

The 1st Armored Brigade was assigned to the ARVN Airborne Division and ordered to cover the retreat on Route 9. When an NVA prisoner disclosed that two enemy regiments were waiting in ambush a short distance ahead to the east, the 1st Brigade commander, Colonel Nguyen Trong Luat, notified Dong. Dong responded by ordering the airborne commander to conduct an air assault to clear the road, but neither man bothered to inform Luat. To avoid destruction on Route 9, Luat ordered his column to abandon the road—just four miles from the South Vietnamese border—and move onto a jungle trail to find an unguarded way back. After the trail came to a dead end at the steep banks of the Se Pone River, the armored force found itself trapped. The NVA quickly closed in and savage rearguard actions ensued. Two bulldozers were airlifted into the ARVN perimeter to create a ford, and the 1st Armored Brigade’s survivors crossed into South Vietnam on March 23 after a horrific 11-mile detour through the jungle.

By March 25, 45 days after the beginning of the operation, almost all remaining ARVN soldiers and South Vietnamese Marines had left Laos behind. For more than a week, a number of exhausted ARVN soldiers, Marines, and American helicopter crewmen, separated from their units, straggled into American bases after walking out of Laos. For the first time, the ARVN found itself forced to leave behind a substantial number of dead and wounded, a devastating emotional blow to families whose sons had perished in Laos. (For the Vietnamese people, who traditionally held a special reverence for the dead, the inability to bury slain family members in their own country was profoundly traumatic.) Returning ARVN soldiers and Marines certainly did not look like victorious soldiers and without exception believed they had not won a victory. The forward base at Khe Sanh had come under increasing artillery and sapper attacks and on April 6 was abandoned as well. Operation Lam Son 719 was essentially over.

Coming under increasing criticism for terminating the operation so far ahead of schedule, South Vietnamese commanders, in a face-saving gesture, claimed that the incursion into lower Laos to cut the Trail was not yet over. To prove it, ARVN mounted two small airmobile raids into the Moung Nong area, the heart of Base Area 611 that had yet to be touched during Lam Son 719, with a 200-man strong force of elite troops from the 1st ARVN Infantry Division. Neither of the raids, which took place on March 31 and April 6, accomplished anything of real military value.

Thieu flew to Dong Ha to address the survivors of the incursion and claimed the Laos operation “was the biggest victory ever.” During a televised speech on April 7, Nixon asserted, “Tonight I can report that Vietnamization has succeeded.” In Saigon, the American command’s claims of success were more limited in scope. It was clear that the operation had exposed grave deficiencies in South Vietnamese leadership, motivation, and operational ability. The incursion had turned into a disaster, decimating some of the ARVN’s finest units and destroying the confidence that had been slowly built up over the previous three years. American airpower prevented a defeat from becoming a disaster that might have been so complete as to encourage the North Vietnamese to keep moving right into Quang Tri Province.

Though Lam Son 719 probably forestalled a communist offensive across the DMZ set for spring 1971 because enemy units slated for that offensive were diverted to lower Laos, truck traffic on the trail system increased soon after the ARVN withdrawal. Sightings averaged 2,500 vehicles a month within days of Lam Son 719’s termination. The North Vietnamese viewed their efforts on the Route 9 front as a complete success and accelerated expansion of the trail on its western flank that had begun in 1970. After anticommunist Royal Laotian troops withdrew westward in the face of the NVA advance, the logistical artery known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail, 60 miles wide just a few months before, was expanded to 90 miles in width. In both Laos and SouthfVietnam, captured communist documents contained exhortations to the troops to exploit their victory in lower Laos. Thus NVA troops began moving radar equipment and surface-to-air missiles into A Luoi.

That the ARVN reached its objective of Tchepone was of little consequence. Its stay there was brief and the supply caches it discovered disappointing, since most were in the mountains to the east and west. South Vietnam’s forces failed to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail; indeed, infiltration reportedly increased during Lam Son 719 when the North Vietnamese shifted traffic to roads and trails farther west in Laos. In addition to massive equipment losses, the ARVN reported nearly 1,600 men killed in action (a figure believed by many to be far below the actual total) and total casualties as 7,683, or 45 per cent losses, while the Americans suffered 215 men killed, 1,149 wounded, and 38 missing. The North Vietnamese suffered massive losses, especially as a result of massed infantry attacks and B-52 strikes, and their casualties may have approached 13,000. With another 7,000 men wounded or captured, communist losses may have reached or even exceeded 50 percent of their total strength.

What the allies had envisioned as a limited search-and-destroy mission—ARVN had committed only two reinforced Army divisions, one Ranger and one Airborne, and their lone Marine division, about 17,000 men—had turned into an intense, combined arms battle that found ARVN commanders experiencing their bloody baptism of fire in large-scale, conventional armored warfare. In retrospect, the operation had revealed the Saigon government’s shortcomings. Like the late President Ngo Dinh Diem before him, Thieu had pursued a policy of preserving politically dependable military units and declaring phantom victories. In Thieu’s case, caution may have been justified considering the unexpected strength of the enemy response in Laos.

In the end, a key consequence of Lam Son 719 was the decision by the emboldened Politburo in Hanoi to launch a major conventional invasion of South Vietnam in early 1972 that was meant to win the war. The North Vietnamese called it the Nguyen Hue offensive. In the west it was known as the 1972 Easter Offensive. Like Lam Son 719, it also failed in the face of overwhelming U.S. airpower, but it brought the North Vietnamese one step closer to their goal of toppling the South Vietnamese government and reuniting the two countries.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments