By P. Lindsay Powell

On a sultry summer night in 9 BC, 29-year-old commander of Augustus Caesar ’s army in Germania bolted upright in his cot, dripping with sweat. He was not sure whether he had just woken from a nightmare, had a premonition, or seen a ghost. For the first time during the four-year-long campaign, the confidence that had driven him to lead his 35,000 men through an extraordinary adventure to the banks of the Elbe River had suddenly deserted him. Should he continue on or turn back? His decision would change the course of history.

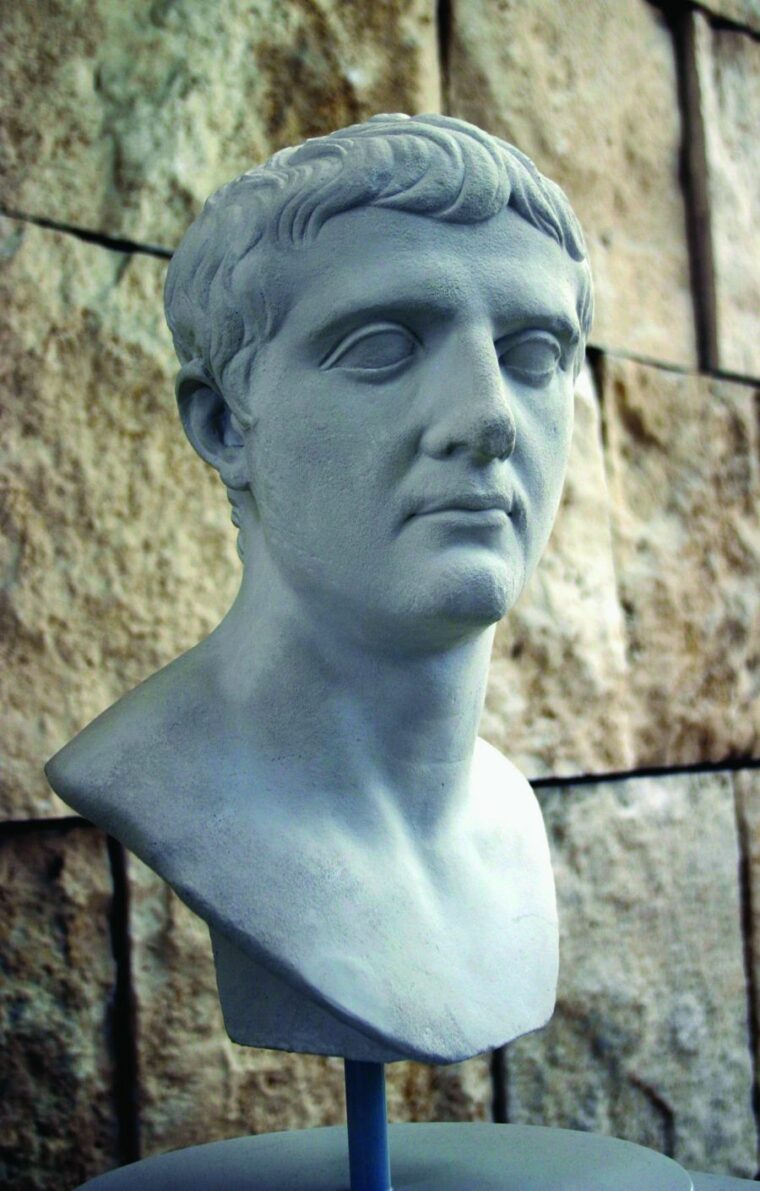

Decimus Claudius Drusus, born on January 14, 38 bc, was the child of Tiberius Claudius Nero and Livia Drusilla. Just months before, Livia had divorced his father, and the young boy and his older brother, also called Tiberius Claudius Nero, had gone to live with their father. Five years later, the father died and the boys were taken back into the care of their mother, who had since married the heir to the great Roman dictator, Gaius Julius Caesar. Formerly known as Gaius Octavianus Thurinus, Augustus Caesar accepted the boys as his own. Drusus received a good classical education, and when he was 20 he married Antonia Minor, daughter of triumvir Marcus Antonius.

With the patronage and sponsorship of his illustrious stepfather, Drusus was fast-tracked through the cursus honorum, the public service career ladder. Five years before the stipulated age, he was elected quaestor by the Roman senate, a position responsible for managing public finances. While serving in this role, Drusus received instructions from his stepfather to meet him in Gaul.

The Lollius Disaster

Augustus was a conservative man by nature, disinclined to take wild gambles and preferring to act only after he had planned his next moves thoroughly. In the 27 years since the assassination of Julius Caesar, Roman armies under his heir had doubled the size of the empire. Until 17 bc, Augustus, as head of state, seemed prepared to accept the Rhine River as the northern limit of his imperial ambitions in the west. That policy abruptly changed when he received news of the so-called Lollius Disaster.

Marcus Lollius was Augustus’s hand-picked man in Gallia Comata, the newly Romanizing regions of France and Belgium. Germanic warriors had crossed the Rhine and raided deep into Gaul, pillaging and destroying villas and towns. Lollius set out to hunt down and punish the culprits. At the top of the list were the Sugambri, Tencteri, and Usipetes tribes, which had formed an alliance. The V (Alaudae) Legion, led in person by Lollius, had been ambushed and its prized eagle standard seized. The Romans saw this as shameful. Furious at the news, Augustus decided to go to Gallia Comata and personally take command of the situation.

In the spring of 16 bc, Augustus began a thorough reexamination of German frontier policy. The Rhine was not an impervious frontier. Roman merchants crossed the river to trade their wares for amber, hides, horses, and iron, and German tribesmen frequently came over in boats to raid the lands to the south. During his subsequent three-year sojourn in Gallia Comata, Augustus thoroughly reviewed the situation on the ground. He understood that the stability of the western end of his empire was closely tied to the intentions of the people across the Rhine. Augustus appointed the 26-year-old Tiberius to replace Lollius as governor and reorganized the region into Tres Galliae.

Decimus Claudius Drusus

Before the conquest of Germania could begin, the central European alpine region would have to be subjugated. By annexing the Alps and the lands up to the Rhine and Danube, the Romans could better police the frontier and support the upcoming German campaign. Augustus appointed his younger stepson, Decimus Claudius Drusus, now 23 years old, to lead the campaign. Drusus was a novice in military affairs, but in the Alps he would quickly learn the arts of war.

At the time, northern Italy was not yet completely within the realm of Rome. Traders traveling between the Roman cities of Aquileia, Verona, and elsewhere in the region were regularly harassed by marauders from the Raeti, a collection of Celtic nations who lived on both sides of the Alps. In 15 bc, at the head of his legions, Drusus swept through the territory, defeating the Raeti at the Battle of Tridentum (modern-day Trento). He then entered the Alps from the south, following the Adige-Etsch River through the Reschen Pass to the Lech Valley and sweeping the remainder of the rebels before him. Several new auxiliary units were created from the men of the captured territories and deployed out of the region. Augustus rewarded Drusus with the title of praetor, a post responsible for administering public justice, which came with six bodyguards (lictores) and permission to wear the purple-bordered royal toga.

Tiberius joined Drusus in a second phase of the campaign, and their joint forces engaged the Vindelici, a tribe that lived in southern Bavaria near the Danube River. Despite stiff resistance, the Vindelici were squashed and Drusus founded a military base that would later become the tribal capital Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg). The two brothers marched eastward to the kingdom of Noricum in the Carinthia-Kärnten region of modern Austria. Famed for its high-quality iron and gold, Noricum was actually a Roman ally, but the Claudius brothers had orders to annex it. They took the capital at Magdalensburg without a struggle. In a single campaign season, Drusus had successfully completed his first mission, and his stepfather appointed him legatus augusti pro praetore. Drusus assumed governorship of the Tres Galliae from his brother, while Tiberius continued to Illyricum to prosecute the war there.

A Massive Military Infrastructure Project

When Augustus left Lugdunum in 13 bc, a plan for the invasion of Magna Germania had already been worked out with his full support and agreement. The goal was to set the new limit of the Roman Empire at the Elbe River, but not necessarily to stop there. Over the next two years, Drusus oversaw the biggest buildup of military infrastructure of the age. Fortresses were established along the Rhine at Vechten, Nijmegen, Xanten, Neuss, and Mainz, with smaller forts scattered between at Moers-Asberg, Bonn, Koblenz, Bingen am Rhein, Speyer, and Strasbourg, all linked by military roads. A canal was constructed between the Ijssel or Vecht and Rhine Rivers to provide access to the Zuiderzee-Ijsselmeer as a way for ships to reach the Wadden Sea. The new route would save the Roman fleet from having to make a dangerous detour through the North Sea.

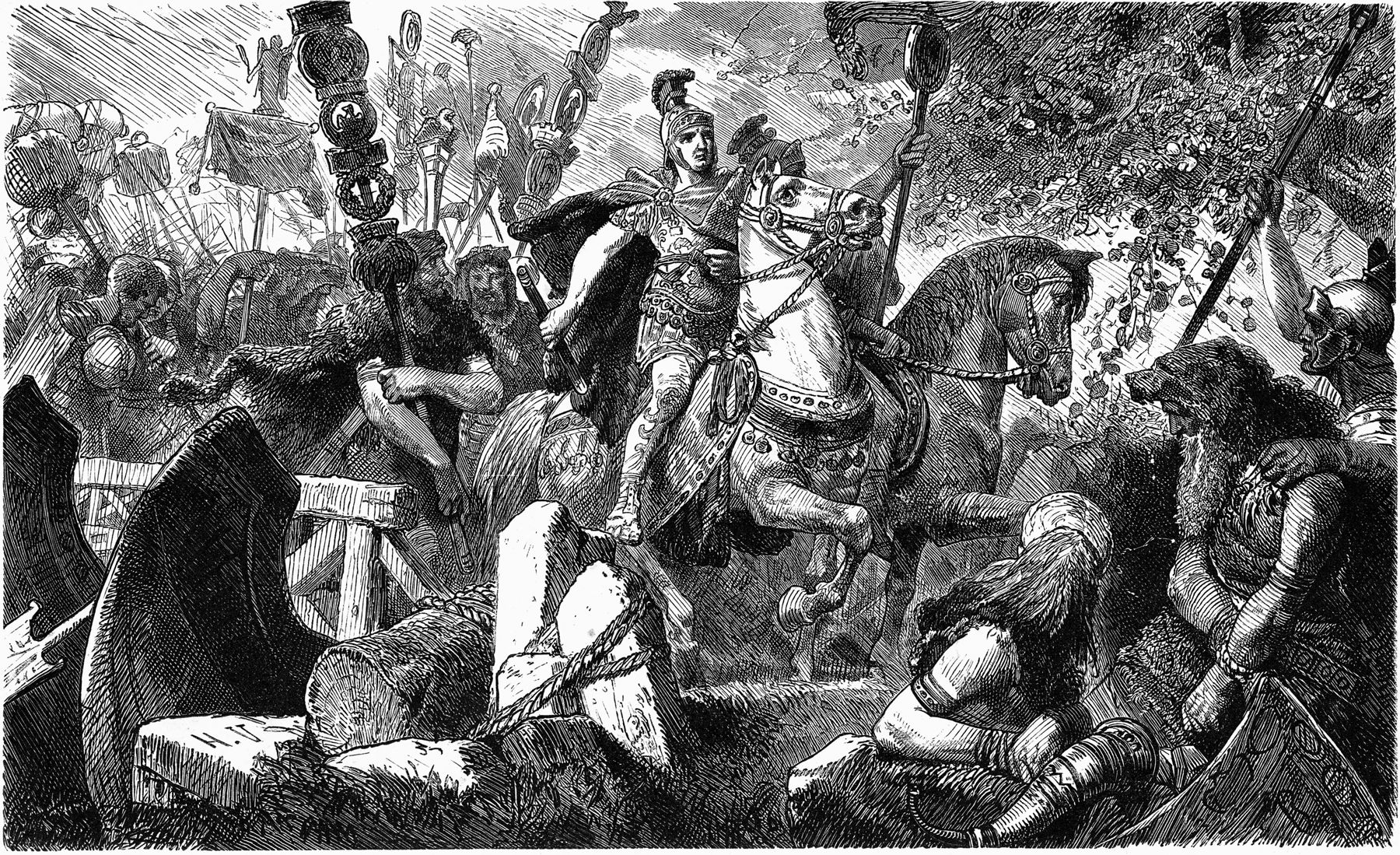

On a spring day in 12 bc, the war in Germania began in earnest when Drusus’s army crossed the Rhine and engaged the Sugambri and Usipete tribes in the region. The swift move neutralized the tribes, and immediately afterward the Romans’ audacious amphibious campaign was launched. Ships carrying as many as four legions sailed down the Rhine past Nijmegen into the Zuiderzee. Drusus completed a treaty with the Cananefates and Frisii tribes to pay tribute and provide men and supplies. The Frisii provided scouts and warriors and accompanied Drusus’s army from that time on.

The fleet sailed into the Wadden Sea, overcoming armed resistance at Burchana before reaching the safety of the estuary of the Ems River. Part of the fleet sailed down the Ems, while the rest sailed along the coast as far as Jutland on an exploratory mission to reach the Caspian Sea, but had to stop after encountering bad weather. Meanwhile, in Germania, Drusus engaged the Chauci and forced them to sue for peace. With the summer drawing to a close, Drusus turned back, retracing the route home. While sailing along the Dutch coast, several of the ships ran aground and were marooned. Frisian allies helped free the stranded ships, and the expeditionary army returned to the Rhine for the winter.

Drusus the Imperator

In 11 bc, Drusus turned his attention to the interior lands. From Vetera (today’s Xanten), his army crossed the Rhine and followed the narrow Lippe River along a 158-mile-long course that wove through North Rhine-Westphalia region. Supported by river craft carrying supplies, the route took Drusus and his troops deep into the land inhabited by the Usipetes, Sugambri, Marsi, Bructeri, and Cherusci nations. Forts were established at Holsterhausen, Beckinghausen, and Oberaden, and a bridge was built over the Lippe. On their way to the Weser, Drusus’s forces encountered the Chatti, who put up a fierce resistance but were beaten back. The Romans constructed a fort in the Taunus Mountains and settled in for the winter in preparation for a renewed campaign the following year. It was the first time that Roman troops had spent a winter on the right bank of the Rhine.

On the return journey, the army was ambushed by the Cherusci at Arbalo. It was a classic Germanic hit-and-run ambush, executed quickly using the forest for protection and surprise. The Roman army was in formation, strung out over many miles, with its baggage under guard but still vulnerable to attack. The Cherusci gained the upper hand during the attack, but did not press home their advantage. The Romans managed to fight the battle to a draw and continued retreating.

In an attempt to secure his gains, Drusus posted garrison forces at Oberaden and Haltern. He then led his battered army back to the Rhine, where the troops acclaimed him Imperator, or commander. This was a traditional honor bestowed on a military leader by his citizen-soldiers for bringing them an exceptional victory. At this time it was a purely military term and had not yet become synonymous with the cognomen emperor. Augustus granted Drusus further honors, allowing him to ride in triumph through the streets of Rome.

In 10 bc, Drusus advanced again into Germania, following the Main River and hoping to reach the Elbe. The route took them headlong into conflict with the Chatti. The Chatti had formed an alliance with the Sugambri, and their combined forces engaged the Romans near Mattium (modern-day Kassel) in the Taunus Mountains. The Romans punched their way through and made it to the Weser River and some distance beyond, but had to turn back when winter approached.

The Fall of a National Hero

In recognition of his latest achievement, Drusus was elected consul in 9 bc. He returned to the front, more determined than ever to reach the Elbe. In a brutal slash-and- burn campaign, the expeditionary force marched single-mindedly to Mogontiacum, finally reaching the Elbe that summer. True to his nature, Drusus was eager to cross the river and drive deeper into Suebi territory. Then something out of the ordinary happened. He had what he evidently believed was a supernatural encounter. One night, Drusus said, he was visited by a fearsome giant, a female Germanic ghoul that demanded—in Latin—that he leave her homeland immediately, warning that his days were numbered. Rather than advance further, he ordered his men to erect a monument at Magdeburg, then return home. It was a literal turning point in his career.

It should have been a routine march, but somewhere between the Saal and Weser Rivers, Drusus was accidentally injured, falling off his horse, which collapsed on his leg. On receiving the news, his brother urgently rode from Pavia, covering hundreds of miles and arriving just in time to catch Drusus’s last words. Thirty days after his fall, at a place that his troops fatalistically called Castra Scelerata, meaning “the Accursed Fort,” Drusus died. He was 29 years old. Tiberius personally walked ahead of the funeral cortège along the entire route to Rome. Crowds turned out to watch and wail as the procession passed through the towns of Gaul and Italy. In Rome, the body laid in state in the Forum after a funerary procession toured the city. The body was burned and Drusus’s ashes placed in Augustus’s own mausoleum. The entire nation mourned. The senate proclaimed him fecundi ingeni, or fecund genius, and posthumously granted him the unique surtitle Germanicus, meaning “conqueror of Germania,” an honor passed along to his two sons.

Romans looked back fondly at Drusus as a national hero. His memory was universally celebrated, and annual racing competitions were held in his honor throughout Tres Galliae. A triumphal arch and statues were erected in Rome, while in Mogontiacum soldiers erected the tallest tower north of the Alps as a memorial to him. After the Roman military disaster at Teutoburg Forest in ad 9, his eldest son Germanicus took command of military operations in Germania that were largely based on his father’s earlier blueprints. When Drusus’s youngest son Claudius became princeps in ad 41, he boosted his image by issuing a series of coins commemorating his father. Over the subsequent centuries, Drusus’s celebrity and achievements have faded, but the towns and cities along the Rhine that make up the backbone of modern-day Germany and the Netherlands remain an enduring legacy.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments