By Joshua Shepherd

Late on the evening of June 13, 1645, King Charles I convened a hurried council with senior officers of the Royalist army at the village of Market Harborough in England’s East Midlands. The king hoped to decide the best course of action against the rebellious Parliamentarians by consulting with Lord George Digby, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, and other high-ranking officers. The king had just received intelligence that a Parliamentarian army had bivouacked six miles to the south near the village of Naseby, and it was imperative that he and his senior officers take immediate steps to counter the threat.

Amid the flicker of candlelight, features sharpened as the men bickered over how best to respond. Little was known for certain regarding Parliamentarian strength and dispositions. Prince Rupert, who was the king’s nephew, opposed a direct move against the enemy, arguing for caution. At that point in the conflict, Rupert commanded the king’s army, although the king still accompanied his troops in the field. In contrast, Digby and other officers, many of whom were disaffected with Rupert’s leadership, argued aggressively for an immediate strike against the seditious Parliamentarians.

After the officers voiced their opinions, all eyes turned to the king. Despite his pretentions to royal prerogative, Charles was a pliable monarch who was known to adopt the last advice that he heard. The king, who detested being chased by what he regarded as a band of rebels, decided the matter. He declared that the army would immediately seek battle.

“Resolutions were taken out to fight,” wrote Sir Edward Walker, the secretary of the king’s Council of War. The following day, Prince Rupert, who still commanded the Royalist army on the field of battle, would get another crack at the Parliamentarian army in a struggle that had dragged on for three years.

The battle that would unfold the following day on the fields of Naseby was the culmination of a long-standing power struggle between king and Parliament. That body had experienced a rocky relationship with the monarch as soon as he ascended the throne in 1625. That same year, with little input from Parliament, Charles wed the French Princess Henrietta Maria. The king’s marriage to a Roman Catholic alarmed the unbending Puritan faction in Parliament. Moreover, Charles’ overweening insistence on unbounded crown rights was pushing the English nation towards the terror of an internecine civil war.

Charles’ stubborn attachment to George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham, precipitated a complete collapse of cooperation between king and Parliament. Buckingham headed up a string of disastrous military excursions against France and Spain, and in the wake of the debacles, the House of Commons demanded Buckingham’s removal. When the king refused, the House of Commons, the only body in England empowered to levy taxes, refused to provide more revenue to the king.

The situation rapidly degenerated as both sides adopted a hard line. The king dismissed Parliament in June 1628. Two months later Buckingham was mysteriously assassinated. Far from seeking accommodation, Charles progressively attempted to expand his own power. The Parliament of 1629 resisted the king’s attempts to adjourn it. For the next 11 years, the king ruled without the nation’s representative body. He sought to collect revenue outside of the traditional legal vehicle of Parliament.

Through levying a series of his own novel—and often extra-legal—taxes, Charles succeeded in alienating a good portion of his subjects. The king collected naval taxes, which were generally collected during wartime, throughout England, and likewise exacted heavy fines for minor infractions and trumped-up offenses.

The king’s insistence on enforcing Anglican rites throughout his realm only served to further anger England’s Puritan faction, as well as Scottish Presbyterians. A Scottish rebellion erupted in 1639, but Charles, unable to raise the necessary funds without the assistance of Parliament, was unable to quash the revolt.

The final breach took place early in 1642. Determined to arrest five members of Parliament that he was convinced had aided the Scottish Rebels, Charles took the unprecedented step of entering Parliament with an armed guard and demanding the surrender of the five men. Although the members were absent, the king’s effort to forcibly enter Parliament was widely considered an unacceptable breach of the English Constitution and only served to cement his reputation as an absolutist monarch. This action by the king directly precipitated armed conflict. Afterwards, both sides scrambled to secure fortresses, arsenals, and popular support.

Charles raised the royal standard at Nottingham on August 22, 1642, officially ushering in the long-feared civil war. Both sides scrambled to raise armies composed of local militia units. The king, driven from London but holding court from Oxford, controlled much of northern and western England, as well as Wales. Parliament, which retained control of London, drew its support largely from southern and eastern England.

For the next two years, the two sides maneuvered against each other and fought various battles and sieges throughout England, but neither was able to gain the upper hand. Parliament’s lackluster command, poor coordination, and outright bad luck ensured that, although the king’s troops were badly handled, his army always slipped away intact.

It became apparent to members of Parliament that it had to undertake a major shakeup in the high command and organization of its forces in order to break the stalemate and achieve victory. Largely jettisoning the three field armies that had previously waged war against the king, Parliament authorized the New Model Army in February 1645. Organized and trained along the lines of King Gustavus Adolphus’ Swedish Army, the New Model Army replaced the part-time militia of the period with a full-time, professional body of troops. Sir Thomas Fairfax, a competent and proven field commander, was given overall command of the reinvigorated army.

The New Model Army, which contained a solid core of experienced veterans, was expanded with fresh recruits. Veterans and recruits alike were subjected to constant drill and rigid discipline to ensure they were ready for battle. Particular attention was paid to the officer corps. Promotion was based on merit, not social standing, ensuring that politically connected but incompetent officers could be weeded from command. Crucial to the improvement of the officer corps were statutory requirements ensuring that members of Parliament could not serve in the army.

Oliver Cromwell, the rising star of the Parliamentarian forces, was the notable exception to that rule. Born to middling gentry stock, Cromwell was a devout Puritan and, at the outset of the Civil War, a member of Parliament. As a vocal opponent of the king’s abuse of power, it was no surprise that he took up arms for Parliament. Although he possessed no appreciable military experience, Cromwell raised a troop of cavalry and quickly proved his worth as a reliable subordinate, natural leader, and fierce fighter. Although he began serving in the field in 1643 with the rank of colonel, he was promoted to Lieutenant General of the Horse the following year.

A stern disciplinarian who earned the nickname “Old Ironsides,” Cromwell nonetheless exhibited a genuine regard for the welfare of his men. His cavalrymen, also known as Ironsides, responded with a reciprocal loyalty, and became one of Parliament’s crack units.

True to his republican leanings, Cromwell had little use for the deference usually granted to the upper classes of society; instead, he opted to promote men who possessed genuine military merit. He scorned the tradition of appointing upper-class gentlemen to the commissioned ranks regardless of the skills they possessed. “I had rather have a plain russet-coated captain that knows what he fights for and loves what he knows, than that which you call a gentleman and is nothing else,” he wrote. “I honor a gentleman that is so indeed.”

When the campaign season of 1645 began, both sides failed to implement a cohesive strategic vision and largely split up their forces to carry out smaller operations. Although Fairfax led much of the New Model Army to relieve the Parliamentarian city of Taunton in southwest England, Cromwell’s cavalry was ordered to harass Royalists in the vicinity of Oxford. Charles waffled over his various options, which included a direct confrontation with the New Model Army or a renewed campaign in northern England, where the Royalist army had suffered a decisive defeat the previous summer at Marston Moor.

Subsequent events put the two sides onto a collision course that would end in central England. The Royalist army groped its way northwest out of Oxford on May 7, pointlessly burning a succession of magnificent manor houses and struggling to protect its supply lines from roving bands of Rebel cavalry. Fairfax, on his way to Taunton, received orders to change directions. At the same time, Parliament’s Committee of Both Kingdoms ordered the New Model Army to head north and lay siege to the Royalist capital at Oxford.

Alarmed by the development and hoping to relieve the pressure on Oxford, Charles turned east and invested the Parliamentary town of Leicester. A brief siege of the town ended on May 31, when Royalist forces stormed the city in an orgy of bloodshed and widespread plundering. “There were many Scots in this town, and no quarter was given to any in the heat,” wrote Richard Symonds, a trooper in the King’s Lifeguard of Horse.

The Royalist victory clearly demanded a response. Fairfax abandoned his siege of Oxford on June 5 and headed north, hoping to shield the region from further depredations by the king’s forces. As Parliamentarian forces continued to consolidate under Fairfax’s command, Charles occupied the town of Market Harborough. Although he suspected that his forces were outnumbered, Charles ultimately chose to seek pitched battle with the Parliamentarians.

Although Charles was considered the titular head of the Royalist army, Rupert had been made General of the King’s Army in autumn 1644 despite his defeat at Marston Moor. The dashing 25-year-old nobleman, whose military career had begun in the latter part of the Thirty Years War on the European Continent, had volunteered to serve his uncle at the outset of the English Civil War. As the two armies jockeyed for position in June 1645, Rupert dutifully obeyed the king’s desire to give battle; however, he believed that direct confrontation with the numerically superior and seemingly formidable New Model Army was inadvisable.

On the evening of June 13, a cavalry clash north of the village of Naseby revealed that the two armies had come within striking distance of each other. Fairfax, who had consolidated an appreciable army of 13,500 men, was eager to pursue the king and give battle. King Charles likewise decided to fight. In the early morning hours of June 14, the Royalists marched south out of Market Harborough.

That morning, the village of Naseby was blanketed in fog. Situated in England’s Northampton County, Naseby was a quiet village that boasted tidy rows of thatched cottages that exemplified the pastoral simplicity of the East Midlands. But as thousands of armed men began to converge on the area, it was apparent that the rural tranquility that Naseby had enjoyed for generations would be shattered in the coming day.

As the morning’s fog began to burn off, the two sides were in sight of each other across a broad valley. Fairfax could see large numbers of Royalist cavalry already formed, with infantry moving up fast. The Parliamentarians had initially formed for battle on an imposing ridge just north of Naseby. But the ridge was fronted by an inordinately steep slope that was cut by rugged draws, and it was apparent that it would be suicidal for the Royalists to attack such a strong position.

Cromwell was always itching for a fight. Hoping to provoke a battle, he turned to Fairfax and suggested shifting the line to the left, where a gentler slope would encourage an enemy attack but still offer good prospects for victory. “I beseech you, draw back to yonder hill, which will encourage the enemy to charge us, which they cannot do in that place, without their absolute ruin,” pleaded Cromwell.

Filing off to the left, the New Model Army took up positions across the top of a deceptively gentle ridge. In a successful effort to conceal his true numbers, Fairfax drew the bulk of his army back from the crest. The center of the position was dominated by Mill Hill. The army’s right flank was protected by Lodge Hill, which was covered by a rabbit warren, whose dens would be dangerous to any advancing cavalry.

Fairfax’s right wing of horse, commanded by Cromwell, included veteran cavalry outfits that would be invaluable in the coming fight. The infantry, consisting of nine regiments in two lines, was under the command of Sergeant Major General Philip Skippon. Fairfax’s left wing of horse was under the command of Colonel Henry Ireton, the army’s commissary general of horse and a close associate of Cromwell. Fairfax positioned a thin screen of musketeers in front of the army. They were tasked with breaking up enemy attacking formations before they struck the main line of the Parliamentarian army.

The Royalists, positioned along a ridge dominated by Dust Hill, were in high spirits as they formed for battle. With 10,000 men under his command, Prince Rupert led some of the finest regiments in England, which included a good proportion of veterans who had seen extensive action. Rupert’s line of battle was well-planned and conventionally arranged. His left flank was protected by five regiments of cavalry under the command of Colonel Sir Marmaduke Langdale. The Royalist center was composed of a solid core of infantry, both musketeers and pikemen, under the overall command of Maj. Gen. Sir Jacob Astley.

As the Royalists made their last-minute dispositions across the valley floor, Cromwell noticed an irresistible tactical opportunity. Running perpendicular to the enemy’s right was the western boundary of Naseby Parrish, known as Sulby Hedges. To Cromwell’s well-trained eye, the hedges offered an ideal position from which to harass an exposed Royalist flank; therefore, he acted quickly to exploit the weakness.

Cromwell dashed off in search of a unit that was, as yet, undeployed. In the rear of the main line he found was he was looking for: an outfit of dragoons under the command of Colonel John Okey. Okey was distributing ammunition to his men when Cromwell showed up and ordered Okey to flank the Royalist right.

A dedicated Parliamentarian and hard-hitting field commander, Okey was an ideal man for the job. Additionally, his dragoons were particularly well-suited for the assignment. Although equipped with swords for close-quarters fighting, the dragoons were armed with muskets and fought dismounted. In the fight that would unfold on the rolling fields of Naseby, Okey’s men would serve as an invaluable source of mobile firepower.

Quickly making for the open pasture to the west of Sulby Hedges, the dragoons galloped north until they neared the Royalist flank. While one man in 10 was detailed to hold the reins of the dragoons’ horses, the rest of the men advanced dismounted toward the hedge. The element of surprise, though, seemed to have been lost: As they made their way into position, they were seen by Royalist troops on the opposite side of the hedge.

Prince Maurice’s cavalry was accompanied by a detachment of musketeers, troops who were well-equipped to fend off Okey’s dragoons. As the two sides nervously eyed each other, a sharp exchange of gunfire erupted. The bark of musketry over Sulby Hedges could be heard across the field, and heralded the beginning of a major fight.

Although the hedgerow served as a reasonable shield from a cavalry charge, it offered no protection from small-arms fire. Rather than be drawn into a protracted and pointless gun battle with enemy musketeers, Okey wisely pulled his dragoons a bit south along Sulby Hedges to low ground that offered better cover for his men. By disengaging from the musketeers, Okey was able to keep his unit intact for his primary mission of harassing the enemy cavalry’s right flank.

But far from pulling out of the fight, Okey’s men were clearly eager to have at the Royalists. From their new position, the dragoons opened fire, sending a sheet of musket fire over the hedge that scorched the enemy flank. It was a one-sided fight, and the dragoons were enjoying it. Okey’s men targeted the Royalist horsemen “with shooting and rejoicing,” wrote their commander.

On the opposite side of the hedge, both horse and rider grew understandably jittery at the incoming fire. Rather than subject themselves to further punishment, the Royalist cavalry bolted forward toward the main Parliamentarian line. Since Okey’s dragoons had unexpectedly chewed up the Royalist right, Prince Rupert’s meticulously planned attack had been launched prematurely.

Prince Rupert joined his troopers in person, and the entire right wing of cavalry, anxious to get at the Rebels, gave spur to their mounts. Their charge rapidly took them across the narrow valley that separated the two armies. Watching the attack unfold from the heights above, Ireton responded immediately, ordering his own cavalry forward to meet the oncoming Royalists. From the hedgerow, Okey’s dragoons maintained a harassing fire into the flank and rear of the Royalist cavalry. Near the bottom of the valley, Rupert’s horsemen, their ranks disordered by boggy ground, hastily reformed, then charged again.

Ireton’s cavalry, galloping full-speed downhill, crashed into the Royalists on the downward slope of Sulby Hill. With barking pistols and flashing swords, a furious melee developed. On Ireton’s left, Colonel John Butler’s Regiment, which had been slow in mounting their charge, was bowled over by the momentum of the Royalist cavalry. Butler was badly wounded and his men pushed out of the way.

From the hedges Colonel Okey witnessed the threat to Ireton’s left and unleashed a galling fire into the exposed Royalist flank. But with Butler’s regiment broken, there was little to stop the Royalists. Charging straight ahead, Rupert’s cavalry crashed through Ireton’s reserves and plunged into the Parliamentary rear.

On Butler’s right the Parliamentarian cavalry got the better of the fight, slamming into the Royalist horse and throwing them back. Two Royalist regiments turned for the rear, and another, panicked by the confusion, joined in the retreat. Yet the fight was far from over. Despite the Royalist cavalry on the right having launched their attack prematurely, the King’s infantry was following hard on their heels, and Fairfax’s Parliamentarian army would have no respite.

The Royalist foot, with shouldered arms and colors flying, came on gamely. Due to the fact that the Parliamentarian line had been pulled back behind the crest of the ridge, the Royalists proceeded blindly and were largely unsure of their enemy’s precise dispositions. As they crested the ridge, though, they were met with a dispiriting sight. Arrayed directly in front of them was the dense first line of the New Model Army, resplendent in their red coats and preparing to fire from close range.

Neither side had much time to react. A sheet of flame erupted from the Parliamentarians, but the gunfire had remarkably little effect on the Royalists. Much of the musketry, fired by nervous new recruits to the New Model Army, had been aimed too high and passed harmlessly over the heads of the Royalists.

Exhilarated that they had closed with the Rebels without being subjected to effective musketry, the Royalists pushed to close quarters, and a savage melee ensued. The Royalists, wielding swords and clubbed muskets, slashed and bludgeoned their way through the front line of the Parliamentarian foot.

Unnerved by the unexpected fury of the Royalist attacks, the troops in the center of Fairfax’s line began to give way almost immediately. Two regiments, those commanded by Sir Hardress Waller and Colonel John Pickering, cracked under the pressure and began falling back in a good measure of confusion. Parliamentarian officers, shouting above the gunfire, tried to rally their men, but were far from successful. Terrified men streamed into the ranks of the Parliamentarian second line, spreading panic like a contagion.

The sudden collapse of the Parliamentarian center uncovered the flanks of the regiments positioned on both ends of Fairfax’s front line. The extreme left of the line, occupied by Skippon’s Regiment, had been left relatively unscathed by the Royalist musketry, but now found itself in a brutal close-quarters fight. Skippon, their commander, was a stern man; for most of his adult life, he had known little else than fighting. A staunch Puritan, Skippon had seen lengthy service with Protestant armies in Holland and Bohemia during the Thirty Years War.

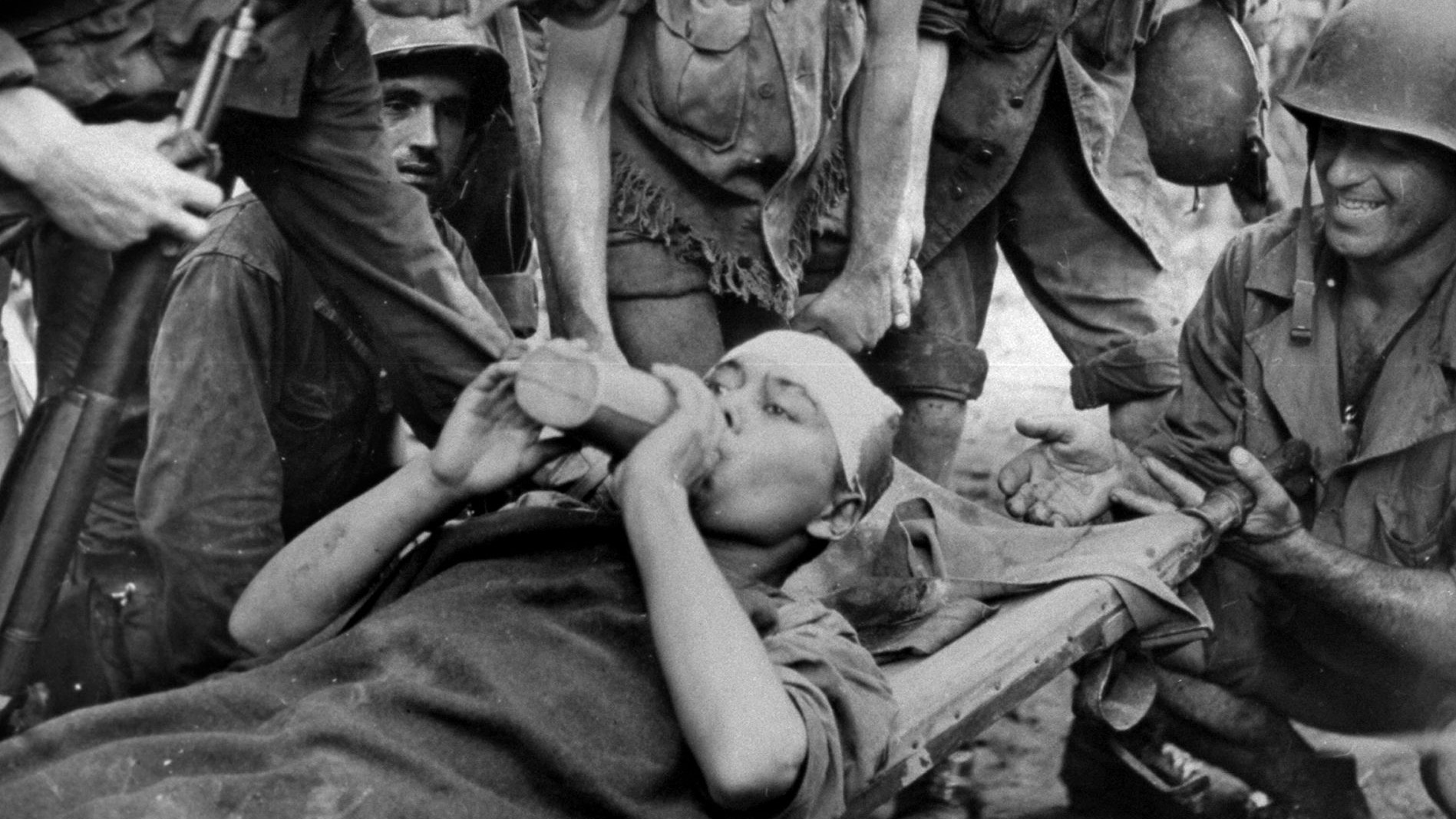

At Naseby, Skippon was in his element. Early in the fight, a musket ball had crashed into Skippon’s right side, punching through his breastplate and leaving a bullet hole just under his ribs. But with Royalists bearing down on his men, Skippon refused to quit the field. Thundering from his saddle and in great pain, Skippon barked orders to his troops and, with the help of a handful of stray horsemen from Ireton’s cavalry, succeeded in slowing the momentum of the enemy’s attack.

Yet their bold stand failed to turn back the main thrust of the Royalist charge, which had collapsed the center of the first rank of the Parliamentarian infantry. Sensing victory within reach, the Royalist infantry surged forward, driving a deep salient into Fairfax’s rear line. For the untested recruits of the New Model Army, their first experience in the field was indeed a baptism of fire.

The rigid training and discipline to which they had been subjected, however, began to pay dividends. With Royalist troops massing in the center of the line but unable to break through, they became increasingly vulnerable. Parliamentarian officers succeeded in steadying their men and stabilizing their lines, then began aggressively pushing back. The Royalists, by that time dangerously overextended and outflanked on each end of their line, had no choice but to give ground.

Almost imperceptibly, the momentum of the battle had suddenly shifted in Fairfax’s favor. With renewed energy, the Parliamentarian infantry pressed forward, quickly gaining possession of the high ground at the top of the ridge and driving the Royalists back down the slope. But an even greater peril was unfolding on their left, where disaster loomed.

Although the Royalist horse had experienced stunning success against Ireton’s cavalry on the right, they ran against a solid wall of Parliamentarian forces on the opposite end of the line. The king’s Northern Horse, consisting of three divisions of cavalry under the command of Colonel Langdale, struggled to launch an effective charge. Brushy ground, paired with the presence of an extensive rabbit warren, slowed their pace and wrought havoc with their dispositions. As the troopers of the Northern Horse carefully plodded their way around the dangerous holes and dens of the warren, Cromwell’s Parliamentarian cavalry had ample time to prepare for the attack.

When the two sides finally clashed, the fight was sharp but decisive. Langdale’s cavalry pushed against the Parliamentarian line, and the brunt of their attack fell on Colonel Edward Whalley’s Regiment. Whalley’s men held firm, and the Royalists, unable to make any headway, began to fall back. With the Royalist infantry falling back in the center and the king’s Northern Horse turned back in front of him, Cromwell was quick to act. Smelling the blood of a demoralized enemy and eager to exploit an advantage, he ordered a counterattack.

After navigating their way through the worst of the terrain, the Rebel cavalry reorganized and charged into Langdale’s horse. Thundering across open ground, the Parliamentarians shattered the Royalist cavalry, which quickly broke apart and fled across the open expanse of the valley.

But as he pressed forward, Cromwell sensed another irresistible opportunity. To his left, the hard-pressed Royalist infantry was retreating downhill in mounting confusion. Their front was increasingly threatened by Fairfax’s infantry, and, due to the flight of Langdale’s Northern Horse, their left flank was dangerously exposed. The situation was a cavalryman’s dream, and Cromwell, needing no further prodding, acted immediately.

While the front line of his cavalry continued a spirited pursuit of Langdale’s broken Northern Horse, Cromwell pivoted his reserves in a wide arc to the left, charging into the open flank of the Royalist infantry. Spurring their mounts and wildly swinging swords, Cromwell’s horsemen tore through the confused ranks of the enemy infantry, bowling men over in a wild killing spree. For the Royalists, what had been a disorganized retreat degenerated into a chaotic rout.

Unit cohesion broke down as panicked Royalists fled for the rear. Exultant that the tide of battle had obviously turned in their favor, the Parliamentarian infantry pressed their advantage, staying close on the heels of the Royalists as the fighting swept across the valley. As their will to fight evaporated, increasing numbers of the king’s foot soldiers threw down their arms and pleaded for quarter.

More of Fairfax’s men rallied as the New Model Army went on the offensive. Much of Ireton’s cavalry, after having been driven from the field earlier in the fight, swung around the army’s right flank, adding their weight of numbers to Cromwell’s horse. Fairfax was swept up in the moment, personally charging forward with his men and crossing sabers with the Royalists. Junior officers tried to pull him back to safety, but not before his helmet was knocked off his head.

As the king’s infantry raced pell-mell for safety, they were greeted by the sight of Prince Rupert’s Bluecoat Regiment of Foot standing firm along Dust Hill. Held in reserve since the start of the fighting, the regiment was one of the most reliable veteran units in the king’s service.

Initially raised in 1642 in southwest England’s Somerset County, the regiment had seen action in the storming of Bolton, sieges of Liverpool and Leicester, and the pitched battle at Marston Moor. Although direct command of the regiment fell to a lieutenant colonel, its ceremonial head was Prince Rupert himself. At Naseby, the Bluecoats would more than live up to their reputation.

While the Bluecoats stood motionless on Dust Hill, the disorganized remnants of the Royalist army swept around their flanks in a mad dash for safety. The regiment, lacking flank support, stood out as a small island of blue along the top of Dust Hill. Parliamentarian infantry and cavalry moved up to attack but failed to break through. Following the wild pursuit of the defeated Royalist army, the Parliamentarian lines had become disjointed, leading to a series of uncoordinated piecemeal attacks against the Bluecoats.

The regiment was attacked repeatedly but stood firm, suffering mounting casualties but refusing to budge. Parliamentarian officers struggled to regain order in their commands, which had become intermingled. Amid the confusion, Fairfax arrived on the scene, and focused his full attention on the growing fight around the Bluecoats.

Realizing that a coordinated attack would likely have better success against stubborn troops, Fairfax developed a simple plan. While Fairfax personally led a mounted detachment to attack from the rear, he instructed D’Oyley to attack simultaneously from the front.

By that time, the Bluecoats had reached their breaking point. When Fairfax and D’Oyley’s men executed the attack, they succeeded in breaking their way into the center of the position. With the Bluecoat’s exterior lines breached, they were quickly beset by swarms of howling Parliamentarians who were determined to inflict a grim retribution. In a swirling melee, the position became a charnel house. Refusing to surrender, the Bluecoats fought to the death. The Parliamentarians shot down or clubbed to death dozens of them.

Charging into the thick of the fight, Fairfax killed the regimental ensign. A Parliamentarian soldier claimed the Royalist standard as his own, and true to character, the lord general refused to claim the flag for himself. “I have honor enough, let him take that to himself,” Fairfax said. Due to the stubborn fight for Dust Hill, the Bluecoats had been nearly annihilated.

The precise chronology is uncertain, but at some point, King Charles nearly entered the fight personally. Watching helplessly as his army virtually disintegrated, Charles prepared to lead his own Lifeguard of Horse into battle in a desperate attempt to slow the advancing Parliamentarians. The prospect of the king directly risking his life in battle alarmed onlookers. According to tradition, the Earl of Carnwath put a stop to it. The furious earl grabbed the reigns of Charles’ mount and impetuously swore at the danger to the king’s person. “Will you go upon your death?” the earl asked his monarch. Brought back to his senses by the rebuke, Charles called off the attack.

With the Bluecoats finally out of the way, there was little to stand in the way of the complete collapse of the king’s army. What ensued was a chaotic retreat to the north as desperate Royalists scrambled to escape the New Model Army. As the flight continued, the king’s forces degenerated to little more than a disorganized mob.

A running rearguard action ensued for several miles as isolated groups of Royalists, urged on by their officers, turned to fire on their pursuers. When the Royalists reached the high ground of Moot Hill, they attempted to make an organized stand but were quickly driven off by superior numbers. Fleeing to nearby Wadborough Hill, they rallied again, but retreated yet again when forced off the hill by Parliamentarian troops.

The fighting degenerated to a wild stampede. Parliamentarian cavalry ran down isolated knots of panic-stricken Royalists, rounding up prisoners by the score. When the Royalist baggage train became trapped on a traffic-clogged country road, mayhem ensued. The army’s terrified female camp followers streamed across an open field in a pathetic attempt to escape. Enraged soldiers from the New Model Army ran amok. Roman Catholic Irish women reportedly were killed outright. The Parliamentarian soldiers delivered a knife cut to the face or nose of other women whom they contemptuously referred to as “the middle sort of ammunition whores.”

Worse horrors awaited Royalist troops at the little village of Marston Trussel. Taking a wrong turn at a village crossroads, dozens of confused soldiers missed the main road north and ended up running down a dead-end street that deposited them on the grounds of the local church and graveyard. Parliamentarian soldiers vengefully cut down helpless Royalist soldiers who found themselves trapped in the churchyard.

The soldiers of the New Model Army seized the primary escape route from Naseby, forcing the survivors of the Royalist army to set out for safety cross-country. They stopped briefly in Leicester, but then resumed their retreat to the northwest. The masses of Royalist soldiers who had been captured in the fighting were housed in any available building. Dozens were herded into confinement in the chapel in Market Harborough; hundreds more eventually made their way to London, where they were ignominiously paraded through the streets in an exultant exhibition of Parliament’s triumph.

Considering the numbers of men engaged, the fight at Naseby had been a bloody affair. Across the slope where the New Model Army had struggled to turn back the enemy, 400 scarlet-clad Parliamentarian troops lay dead or wounded. For the king’s forces, the battle had been nothing short of a disaster. Of the king’s army, 1,000 had been killed and 5,000 more captured. The flower of the Royalist army had been shattered, and with it the king’s cause.

Although Charles would maintain the fight for his throne, the crushing defeat that his army suffered at Naseby had largely sealed his fate. In the wake of the battle, the king’s fortunes would wane, willing recruits would grow increasingly scarce, and royal coffers continued to dry up. On the run from an ascendant Parliament, Charles would never again be able to field a professional and experienced army the likes of which he had sacrificed on the fields of Naseby.

Obliged to surrender himself to Scottish forces in 1646, the king was surrendered to the English Parliament the following year. Charles was eventually tried for waging war against Parliament and the English people, found guilty, and sentenced to death. His grim execution by beheading was carried out on January 30, 1649.

To his last Charles had remained intransigent. The English people possessed no “share in the government; that is nothing appertaining unto them,” he wrote. Although the monarchy was restored in 1660, the rights of the people to representative government had been solidified by the bloody Civil Wars that decimated England. The fate of Charles I, and with him the concept of the divine right of kings, had been decided on the fields of Naseby.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments