By Allyn Vannoy

The first recorded encounter between American forces and Koreans in the Central Pacific during World War II came at Tarawa Atoll in November 1943. After four days of bloody fighting the Japanese fortified islet of Betio was brought under American control. The only survivors of the garrison were 17 Japanese soldiers and 129 Korean laborers who had helped build Tarawa’s pillboxes, bunkers, and gun emplacements, though some of the Koreans may have actively participated in the fighting.

Little has been recorded of the support Korea provided to the defenders of the various island garrisons Japan had spread across the Pacific before and during the war, but how this Korean support came about was a tragedy in itself.

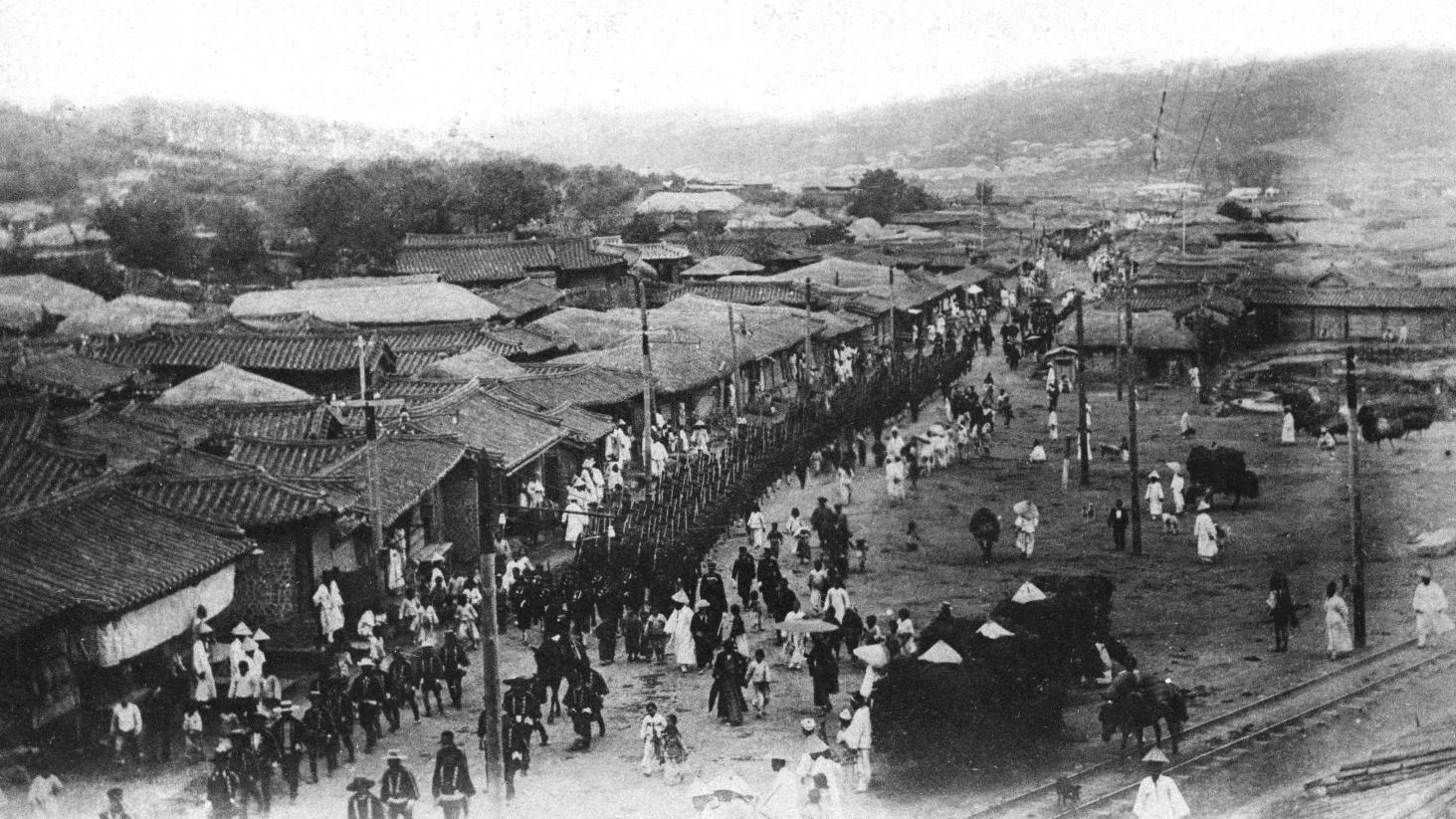

The Conquest of Korea

By 1941, Korea had been under Japanese rule for some 31 years, but the events leading to Japanese occupation began decades before. In 1873, there was considerable debate in Japan concerning whether or not to conquer Korea. One faction of the Japanese government insisted that Japan should confront Korea due to Korea’s refusal to recognize the legitimacy of Emperor Meiji as head of the Empire of Japan, as well as to respond to insulting treatment meted out to Japanese envoys attempting to establish trade and diplomatic relations.

Three years later, the Japanese imposed the Treaty of Ganghwa, which opened three Korean ports to Japanese trade and granted extraterritorial rights to Japanese citizens. Japanese influence increased with the subsequent assassination of Korean Empress Myeongseong, also known as Queen Min, in 1895.

As a result of the struggle for control of northern China and Korea, a simmering rivalry between Russia and Japan eventually exploded into the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, which Japan won. Under the Treaty of Portsmouth, signed in September 1905, Russia acknowledged Japan’s “paramount political, military, and economic interest” in Korea.

Under Japanese pressure the reigning Korean ruler, Emperor Gojong, was forced to relinquish his imperial authority and appoint the crown prince as regent. Japanese officials used this to force the accession of the new emperor, Sunjong, though it was never agreed to by Gojong. Sunjong thus became the last ruler of the Joseon Dynasty, which had been founded in 1392.

Official Annexation of Korea

In May 1910, Japanese Minister of War Terauchi Masatake was given the mission of finalizing Japanese control over Korea after the previous treaties, the Japan-Korea Protocol of 1904 and the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty of 1907, had formalized Korea as a protectorate of Japan and had established Japanese hegemony over Korean domestic politics. On August 22, 1910, Japan effectively annexed Korea with the Japan-Korea Annexation Treaty signed by Lee Wan-Yong, prime minister of Korea, and Masatake, who became the first Japanese governor general of Korea. The governor general answered directly to the Japanese prime minister. All of the subsequent governor generals were high-ranking Japanese military officers.

Upon Emperor Gojong’s death, anti-Japanese rallies took place across Korea, most notably involving the March 1st Movement of 1919. A declaration of independence was read in Seoul. An estimated two million people took part in these rallies. The Japanese responded by violently suppressing the protests. According to Korean records 46,948 were arrested, 7,509 killed, and 15,961 wounded, while the Japanese placed the figures at 8,437 arrested, 553 killed, and 1,409 wounded.

In theory, the Koreans, as subjects of the Japanese emperor, enjoyed the same status as the Japanese, but in fact the Japanese government treated the Koreans as a conquered people. Until 1921 they were not allowed to publish their own newspapers or to organize political or intellectual groups.

With the Japanese occupation of the peninsula, many former Korean soldiers and other volunteers left for Manchuria and Primorsky Krai in Russia. Koreans in Manchuria formed resistance groups known as the Dongnipgun (Liberation Army), crossing the Korean-Chinese border to carry out guerrilla attacks against Japanese forces. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1932 and subsequent pacification of Manchukuo—the Japanese eventually creating a puppet government in Manchuria—deprived many of these resistance groups of their base of operations. They were forced to either flee west to China or to join communist-backed forces in Russia.

Forced Assimilation into the Empire

After 1937, when Japan launched the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) against China, the colonial Japanese government decided on a policy of mobilizing the entire country for war. Not only was the economy reorganized onto a war footing, but the Koreans were to be assimilated into the Japanese Empire. The government began to enlist Korean youths in the Japanese Army as volunteers in 1938 and later as conscripts in 1943. Worship at Shinto shrines became mandatory, and attempts to preserve a Korean national identity were discouraged.

Japanese rule was harsh, particularly after Japanese militarists began their expansionist drive. Internal Korean resistance virtually ceased in the 1930s as police and the military gendarmes imposed strict surveillance and punishments against antigovernment suspects. Most Koreans opted to pay lip service to the colonial Japanese government while some actively collaborated.

On December 9, 1941, the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, formed in opposition to Japanese rule under the presidency of Kim Gu, declared war on Japan and Nazi Germany. The provisional government brought together various Korean resistance groups such as the Korean Liberation Army, which was involved in combat on behalf of the Allies in China and parts of Southeast Asia. Tens of thousands of Koreans volunteered to be part of such groups as well as the National Revolutionary Army and the People’s Liberation Army. The communist-backed Korean Volunteer Army (KVA) was established in Yenan, China, outside of the provisional government’s control, from a core of 1,000 deserters from the Imperial Japanese Army. The KVA eventually entered Manchuria, where it recruited from the ethnic Korean population and became the Korean People’s Army of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Among the noted Koreans that collaborated with the Japanese were Togo Shigenori, a prominent ethnic Korean who served Imperial Japan as a minister of foreign affairs and as a minister of Greater East Asia during the war, and General Hong Sa-ik (Kou Shiyoku), who served in the Imperial Japanese Army.

Even prior to the annexation of Korea, Japanese merchants had begun settling in towns and cities in Korea seeking economic opportunities. By 1910, the number of Japanese in Korea reached over 170,000, creating the largest overseas Japanese community in the world at the time.

Drawing Upon Korea for Labor

From 1939, labor shortages in Japan resulting from the conscription of Japanese males led to official efforts to recruit Koreans to work in Japan, initially through civilian agents and later through coercion. As the labor shortage increased by 1942, Japanese authorities extended provisions of the National Mobilization Law to include the conscription of Korean workers for factories and mines on the Korean peninsula and in Manchukuo, and the involuntary relocation of workers to Japan.

Of some 5,400,000 Koreans conscripted by the Japanese for labor, about 670,000 were taken to Japan, including Karafuto Prefecture, present-day Sakhalin Island. Those who were brought to Japan were often forced to work in coal mines, in military plants and factories, and on military construction, often under appalling and dangerous conditions. An estimated 60,000 died between 1939 and 1945 from harsh treatment, inhumane working conditions, and Allied bombing. The total deaths of Korean forced laborers in Korea and Manchuria was estimated between 270,000 and 810,000.

Beginning in 1938, Koreans both enlisted and were conscripted into the Japanese military as the first “Korean Voluntary” unit. Among notable Korean personnel in the Imperial Army was Crown Prince Euimin, who attained the rank of lieutenant general. Some Koreans who were former Japanese Army personnel later gained administrative positions in the postwar South Korean government. These included Park Chung Hee, who became president of South Korea; Chung Il-Kwon, prime minister from 1964 to 1970; and Paik Sun-Yup, South Korea’s youngest general, famous for his defense of the Pusan Perimeter during the Korean War. The first 10 chiefs of staff of the South Korea Army were graduates of the Imperial Japanese Army Academy.

In 1938, the Japanese began accepting Korean volunteers into the army of Manchukuo, forming the Gando Special Force. This unit specialized in counterinsurgency operations against Communist guerrillas. The unit included such notables as General Paik Sun-Yup, who later served in the Korean War.

Japanese corporations operating under the direction of the Japanese military organized construction units to build military facilities. The Japanese Army and Navy also raised construction units composed of Koreans and led by Japanese officers to work on projects across the Central Pacific, building fortifications on island bases.

In 1944, Japan started the conscription of Koreans into the armed forces. All Korean males were drafted to either join the Imperial Japanese Army or work in military-related industry. Before 1944, approximately 18,000 Koreans were inducted into the Army. From 1944, about 200,000 Korean males were drafted into military service, the total number of Korean military personnel reaching 242,341, of which 22,182 died during the war.

In addition to a large portion of the male population being drafted into the military and construction units during the war, Korean women also became victims of the Japanese comfort women program, serving in Japanese military brothels. The estimated number of comfort women ranged from 10,000 to 200,000, which included Japanese women as well. There were reports that Japanese officials and local collaborators kidnapped or recruited poor rural women from Korea and other nations for sex slavery under the guise of offering them factory employment.

The Allies Encounter Korean Soldiers

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the history of Korea under the Japanese took a final and dramatic turn as the Korean people were brought to the end of a long period of darkness. However, this final stage would come at a terrible cost.

During the fighting in the Pacific, American soldiers and Marines reported that they frequently encountered Koreans within the ranks of Japanese units.

The U.S. advance across the Central Pacific began with the capture of Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Islands. The Japanese were well aware of the Gilberts’ strategic location and had invested considerable time and effort in fortifying the islet of Betio. The garrison included the 7th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force of 2,619 men, an elite Japanese marine-type unit. In order to bolster the island’s defenses 1,247 men of the 111th Pioneers (construction troops) along with 970 men of the Fourth Fleet’s construction battalion were brought to the island. Approximately 1,200 of the men in these two groups were Korean laborers.

The U.S. landing at Makin Atoll encountered a Japanese garrison of 798 troops along with a labor unit consisting of 276 men, “who had no combat training and were not assigned weapons or a battle station,” according to one report. It was believed that most, if not all, of the members of the labor unit were Korean. Shortly after landing the Americans captured about 35 Koreans, and when the operation was completed a total of 105 prisoners had been taken, all but one of whom were noncombatant laborers.

During 1943-1945, Korean POWs taken by American forces in operations in the Central Pacific were brought to Hawaii and held in a camp on the island of Oahu. The camp, located in Honouliuli Gulch a little over three miles west of Pearl Harbor, was opened in March 1943. It was later renamed the Alien Internment Camp and eventually POW Compound Number 6.

Following action in the Gilberts, American forces moved on to the Marshall Islands. The islands of Kwajalein and Roi-Namur were assaulted in January-February 1944, and both Japanese troops and Korean laborers were encountered.

The defense of Roi-Namur left only 51 survivors of an original garrison of 3,500. Though the Kwajalein garrison numbered approximately 8,000 men, less than half were considered combat effective. The actions resulted in 7,870 dead and 105 Japanese soldiers captured along with 125 Korean laborers. To the distress of many Koreans, those Korean laborers who died in the Marshalls were and still are enshrined as war hero guardian spirits of the Japanese nation in the Yasukuni Shrine in Japan.

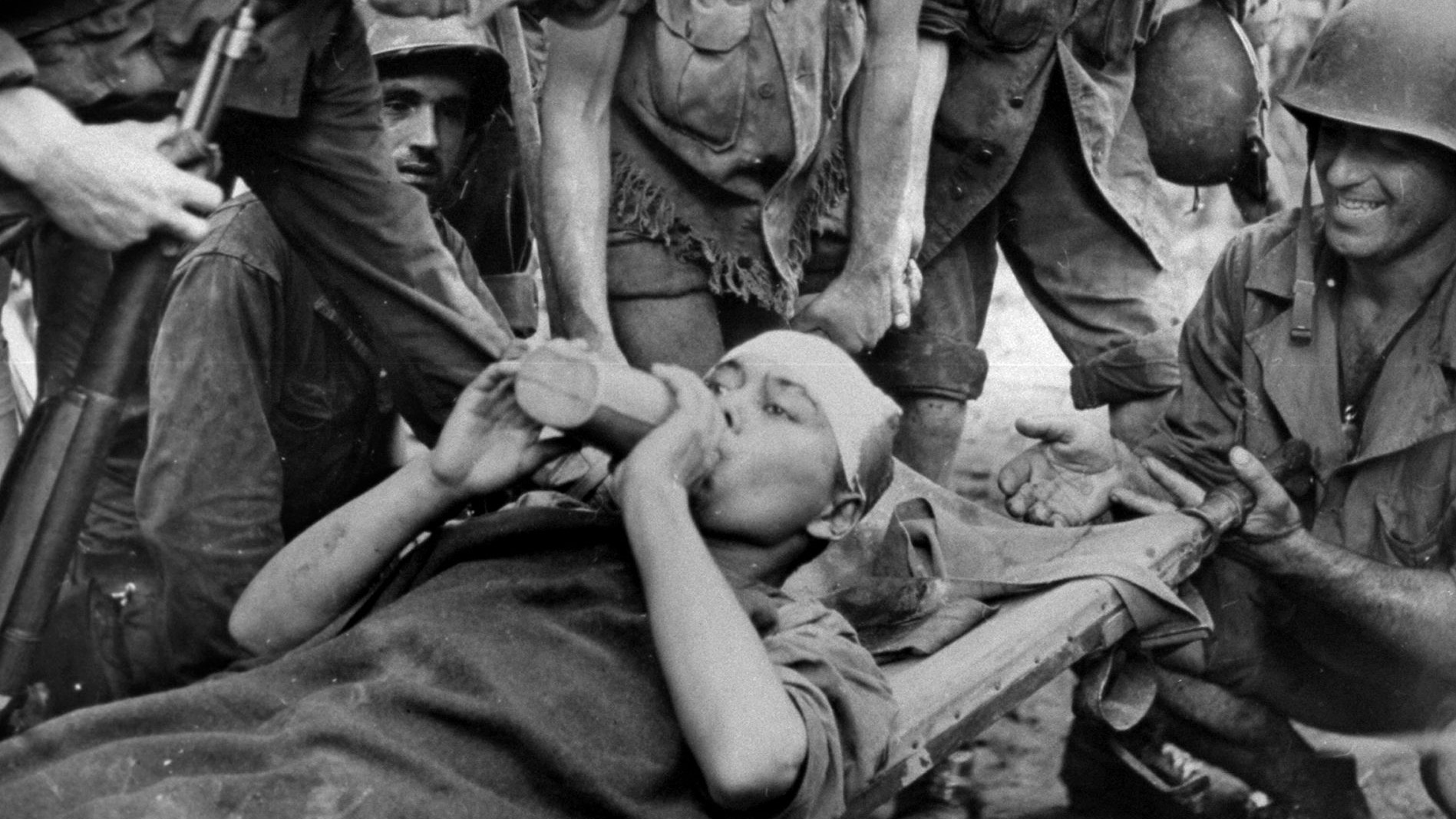

Some 300 to 400 Korean laborers were brought to the Honouliuli camp after the capture of Saipan in the Marianas in the summer of 1944, all of them noncombatant laborers. A number of these Koreans had been wounded. It was believed that most of their wounds had been inflicted by Japanese troops through beating, sword and knife slashing, and other abuses. Some had also received bullet wounds from the fighting as the Americans took control of the island.

It is likely that Korean laborers from various other Pacific islands, such as Guam, Tinian, and Peleliu, were also brought to the Honouliuli camp as POWs. During September 1944, U.S. Marines landed at Peleliu. The island was occupied by approximately 11,000 soldiers of the Japanese 14th Infantry Division, along with Korean and Okinawan laborers. The extremely bloody fighting resulted in 1,794 American dead and 8,010 wounded. Only 202 Japanese survived.

The End of Japanese Occupation

Japan’s formal rule of Korea ended on September 2, 1945, with the nation’s surrender to the Allies. The Korean prisoners held in Hawaii were repatriated to Korea in December 1945, along with many other Koreans from throughout the former Japanese Empire. But the final ending was not happy for all of the Koreans.

After the war, 148 Koreans were convicted of war crimes; 23 of them were sentenced to death. The convicted Koreans included many prison guards who were particularly notorious for their brutality. Justice Bert Röling, who represented the Netherlands at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, noted, “Many of the commanders and guards in POW camps were Koreans and it is said that they were sometimes far more cruel than the Japanese.”

Korean guards were also sent to the jungles of Burma to oversee the construction of the Burma Railway. The highest ranking Korean to be prosecuted after the war was Lt. Gen. Hong Sa-Ik, who was in command of all Japanese prison camps in the Philippines.

The Koreans, as involuntary members of the Japanese Empire, had found themselves in that proverbial position between the rock and the hard place. Without the defeat of the Japanese Empire, Korean culture and the Korean people might have vanished from the world. Today, Korean independence day is celebrated on August 15, 1945, the date of the Japanese surrender ending World War II.

This article is incomplete without an evaluation of the roles of Kim Il Sung and Sigman Rhee. These two became paramount figures after WW2/. They did not just appear but had to have had major roles during the Japanese occupation of Korea.