By Allyn Vannoy

Winston Churchill described the U.S. Army during the war years as a “prodigy of organization … an achievement which soldiers of every other country will always study with admiration and envy.”

Building the U.S. Army into one of the mightiest in world history was done with American “know-how” and technical prowess, but the challenges were enormous.

On July 1, 1939, the strength of the active Army was approximately 174,000, three quarters of whom were scattered throughout the continental United States in over 120 posts, camps, and bases. The other troops were stationed overseas. The existing corps headquarters functioned in only an administrative role, while army commands did not exist. Of the authorized infantry divisions only the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd had a divisional framework.

The Regular Army was supplemented by the National Guard, which had just 200,000 men. The Guard organization had only come into being in 1933. Its state was worse than the Regular Army—short of equipment and weapons, with little opportunity for training. An Organized Reserve, which existed for the purpose of supporting mobilization, contained a pool of over 100,000 trained officers, mainly graduates of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

On September 8, 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a limited national emergency, raising the strength of the Regular Army to 227,000. With the growing war in Europe, the government approved the Selective Service Act in September 1940. This authorized the Army’s strength to increase to 1.4 million men—500,000 Regulars, 270,000 Guardsmen, and 630,000 Selectees. Between October 1940 and July 1941, 17 million men registered for the Draft.

By mid-summer 1941, the Army had increased eightfold. Ground forces were organized into four armies with nine corps containing up to 29 divisions, plus overseas garrisons, including those in Alaska and Newfoundland. But the situation regarding equipment and weapons presented challenges due partially to the need to provide arms to Britain.

The U.S. Army eventually mobilized 91 divisions compared to 120 for the Japanese, 313 German, 50 Commonwealth, and 550 Russian divisions. However, unlike some countries, the American divisions would be maintained near full strength throughout the war. This was not a small task. By early 1945, some 57 regiments in 19 divisions had suffered 100-200 percent casualties.

During the war, approximately 11,200,000 men and women served in the Army. From a strength of 1.6 million in December 1941, the Army reached a peak in March 1945, of 8,157,000 personnel—a near fourfold increase in just over three years. However, only 2.7 million were in the ground forces.

The Army was composed of three elements. The Army Ground Forces provided for combat operations. The Services of Supply (Army Service Forces in 1943) was responsible for supplying and servicing units and included engineers, quartermasters, medical personnel, signal corps, chemical warfare service, ordnance, and military police. The third element was the Army Air Corps, which became the Army Air Forces in 1942. All three commands reported to the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, General George Marshall.

Lieutenant General Lesley McNair became commander of Army Ground Forces in March 1941.

The Army Service Forces commanding officer, 1942 to 1945, Lt. Gen. Brehon Somervell, had led the Construction Division, Quartermaster Corps in 1941, building camps to house and train personnel. The most enduring of his many projects was the Pentagon.

The Army Air Forces commanding officer was General Henry (Hap) Arnold. A supporter of strategic bombing, he laid plans for an Air Force of 60,000 aircraft and 2.1 million personnel. The Army’s air elements included ground support, strategic bombing, troop transport, interdiction or medium-range bombers, and reconnaissance units.

In September 1939, the Army Air Corps had just 800 frontline aircraft. Growth in aircraft production was dramatic—from 4,477 in December 1941 to 43,248 in May 1945.

In 1941, the Army Air Corps had 152,125 personnel, with the AAF reaching a peak strength of over 2.4 million and approximately 80,000 aircraft in 1944, with 1.25 million men stationed overseas, exceeding Arnold’s original plan.

Prior to 1940, basic training was left to individual units. The War Department created special training organizations, Replacement Training Centers, to provide a steady flow of trained personnel. Twelve ground force centers began operations in March 1941—three coastal artillery, one armor, one cavalry, three field artillery, and four infantry. During 1941, they trained over 200,000 men. Later, centers were established for antiaircraft and tank destroyer training. During 1941-43, some 42 centers were in operation.

In addition to RTCs, service schools were set up to train officers, officer candidates, and enlisted specialists. Between July 1940 and August 1945, nearly 570,000 men passed through the schools.

Additional challenges began to appear in mid-1942 due to equipment shortages. Units due for immediate shipment to a combat zone received highest priority. Units sometimes received their allocations so close to embarkation that there was no time to train with their new equipment. Despite these problems, mobilization proceeded at breakneck speed.

In the summer of 1943, the decision was made to build the Army to an effective strength of 7.7 million. By 1945, operating strength reached 8.3 million, including some 600,000 ‘ineffectives’—half a million in hospitals and 100,000 being discharged. Manpower was distributed with 2,340,000 in the Army Air Forces, 1,751,000 in the Army Service Forces, 3,186,000 in the Army Ground Forces, and 423,000 in Theatre Forces.

Army Ground Forces personnel were grouped into divisional and non-divisional forces. Non-divisional forces included service units and additional combat troops not organic to divisions, such as independent artillery, tank, antitank, antiaircraft, and engineer battalions.

The combat arm was organized around the division, the smallest organization capable of performing independent operations. The 91 divisions formed were of five types with the eventual mix including 68 infantry, 16 armored, five airborne, two cavalry (mechanized), and one mountain. Authorized strength by division was infantry—14,253, armored—10,937; airborne—8,596; cavalry—12,724; mountain—14,965.

Division numbering followed a pattern established in 1917. Numbers 1 to 25 were reserved for the Regular Army; numbers 26 to 45 for the National Guard; and numbers 46 to 106 for the Army of the U.S. There were numerous exceptions. Two airborne divisions, the 82nd and 101st, were re-designated Regular Army with conversion from infantry to airborne. The 25th was formed from troops of the Hawaiian Division and classified as an Army of the U.S. division. The 42nd Division was a National Guard division, but mobilized as an Army of the U.S. division.

Eventually, Regular Army divisions included the 1st-9th, 24th, Philippine, 82nd and 101st Airborne, 1st and 2nd Cavalry, and 1st-5th Armored. National Guard divisions included the 26th-41st and 43rd-45th Infantry. Organized Reserve divisions included the 76th-91st and 94th-104th Infantry. All others were Army of the United States divisions, including the 25th, 42nd, 63rd-75th, 92nd and 93rd, 106th, and Americal Infantry, the 10th, 11th, 13th, and 17th Airborne, and the 6th-16th and 20th Armored.

Steps to create a division were extremely tight as the War Department planned to activate three or four per month from March 1942. First there was cadre selection. About 1,300 officers and enlisted men were selected from an existing division to serve as the nucleus of the new division. Then a division commander was selected. The commander was handpicked by General Marshall. Months of cadre training followed prior to activation. Remaining officer slots were filled by officers from schools and replacement centers. The division was then formally activated.

Division expansion came next as draftees and enlistees brought it up to authorized strength. The division trained for a year with 17 weeks of basic and advanced training, 13 weeks of unit training, 14 weeks of combined arms training and large-scale exercises, and eight weeks of final training. Large-scale multi-division exercises followed.

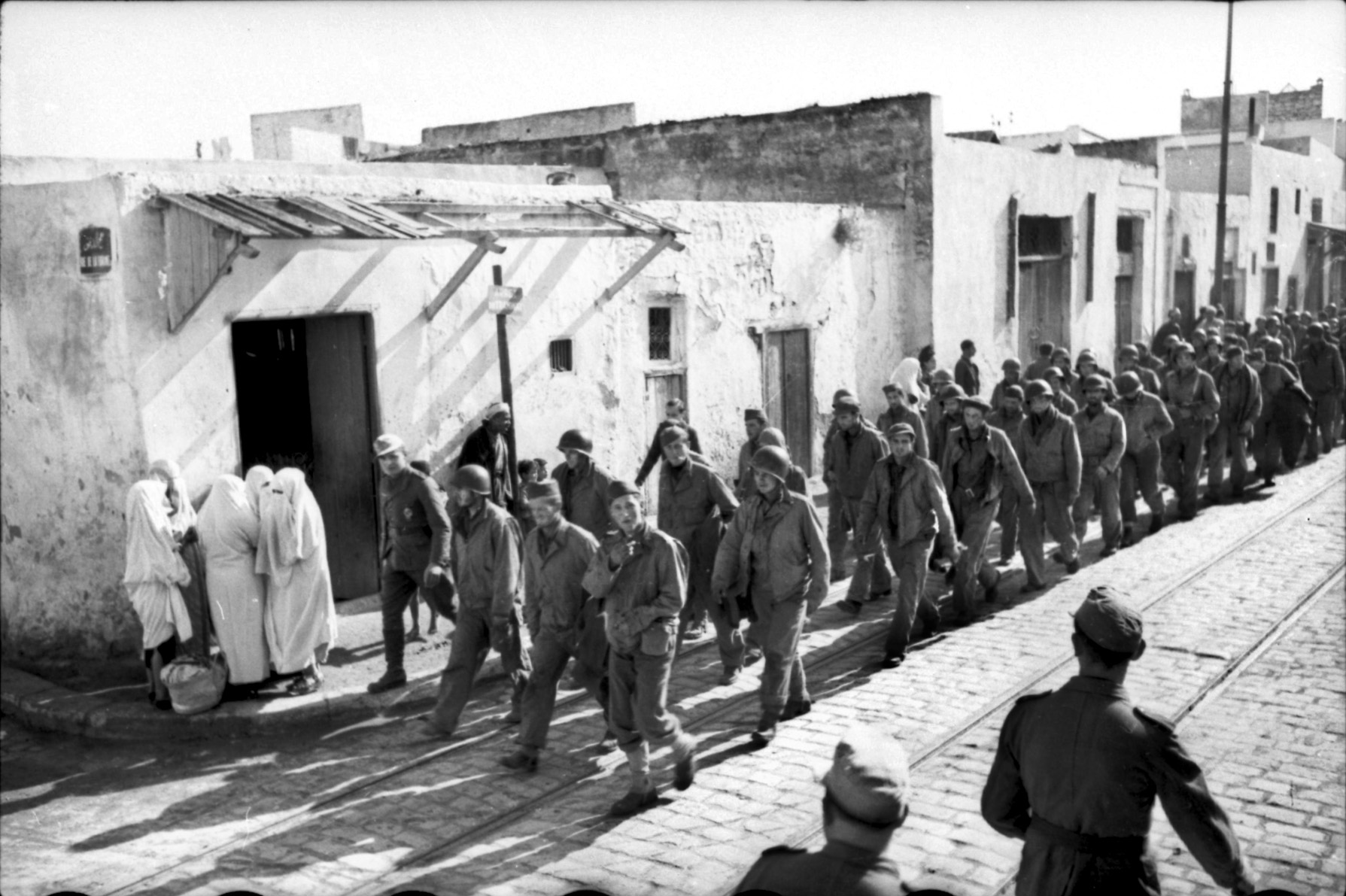

The division then moved to a staging port, loaded on transports, and embarked to an overseas theater. There was sometimes a period of additional training, after the division arrived in theater. The division then moved to the front, where it entered combat.

The Army expanded rapidly from 1939 to 1943, starting with an existing force of just six divisions. Four of these were based in the continental U.S., another in Hawaii, and one in the Philippines. Five were infantry, and one was cavalry. The four continental divisions included the 1st Cavalry and 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Infantry.

All Army divisions were activated in the continental United States except for the Philippine, activated in the Philippines in June 1921, the Hawaiian, activated in February 1921, in Hawaii and later renamed the 24th Division, the 25th Division, also activated in Hawaii from troops of the Hawaiian Division, and the Americal Division, activated in New Caledonia in May 1942.

Divisions were assigned in three theatres of operations during the war: 60 to Europe, 14 to the Mediterranean (North Africa and Italy), of which seven—the 2nd Armored; 82nd Airborne; 1st, 3rd, 9th, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions—were eventually transferred to Western Europe, and 22 divisions in the Pacific.

Two divisions were removed from the rolls during the war. The Philippine Division was destroyed in action and disbanded on Luzon on April 10, 1942. The 2nd Cavalry Division was activated and inactivated twice— April 15, 1941—July 15, 1942, and February 23, 1943 – May 10, 1944. Three divisions never saw combat—the 98th Infantry, activated in September 1942, sent to garrison the Hawaiian Islands in April 1944, the 13th Airborne, activated in July 1943 and deployed to Europe in 1945, and the 2nd Cavalry.

The number of activated Army divisions tripled from eight in early1940, to 24 in January 1941, with another 13 added in the following year— creating 30 infantry, two cavalry, and five armored. After December 7, 1941, 27 infantry, two airborne, and nine armored divisions as the Army’s size doubled to 73 divisions by the end of the next year. Another 17 were added in 1943. The 65th Infantry Division was the last activated in August 1943. The 10th Division was activated in July 1943, as a light division and redesignated the 10th Mountain in November 1944.

In 1942, the US Army deployed 10 divisions to the Pacific and North Africa. Another nine followed in 1943 as Mediterranean operations progressed to Sicily and Italy and expanded across the Pacific. In 1944, with the invasions of France and the Philippines, 45 divisions were added to those fielded, including seven armored and two airborne. In 1945, 23 more divisions were deployed.

In 1942-43, a bulwark of garrisons, some nine divisions, were spread across the Pacific from the 7th Infantry in the Aleutians (moved to Kwajalein in 1944), the 24th and 25th in Hawaii (the 25th would later serve on Guadalcanal), the 27th at Makin, the Americal and 43rd at Guadalcanal, joined in early 1943 by the 37th, which moved from Fiji to the Solomons, and the 32nd and 41st at Papua, New Guinea.

As Allied operations moved closer to Japan, more Army units deployed. Pacific forces were split between those supplementing the Marines in the Central Pacific and those under General Douglas MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific. Serving the Central Pacific were the 77th at Guam in mid-1944; the 27th at Saipan June-July 1944; and the 81st at Peleliu that autumn.

Added to MacArthur’s forces in New Guinea during January 1943–August 1944 were the 1st Cavalry and seven infantry divisions—the 6th, 11th, 24th, 31st, 33rd, 38th, and 93rd.

Four Army infantry divisions participated in the bloody fighting for Okinawa—the 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th. Nineteen divisions saw action in the Philippines, including the veteran 1st Cavalry, 6th, 7th, 24th, 25th, 31st, 32nd, 33rd, 37th, 38th, 40th, 41st, 43rd, 77th, 81st, and Americal, 11th Airborne, and the newly-arrived 96th.

Army forces destined for Western Europe were highly mechanized, a mix of 16 armored and 52 infantry, mountain, and airborne divisions.

While an infantry division could maneuver and fight with its basic organization, it usually had additional assets attached—a tank battalion, an antitank battalion of either towed or self-propelled guns, an engineer battalion, and sometimes additional artillery. Attachments depended on the mission and availability of units.

The last divisions to arrive in the European theater included the 86th and 97th, and the 16th and 20th Armored, during March–May 1945. The 86th appeared in both Europe and the Pacific.

The first three armored divisions, the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd, were all “heavy” divisions, their organization including two tank regiments and an armored infantry regiment—a total of nine battalions. The armored divisions that followed had three tank battalions and three armored-infantry battalions. The armored division also had three tactical command elements, or combat commands, to carry out selected missions.

Attaching and detaching units to divisions presented a constantly changing organization. A company of engineers might be attached to a combat command from corps assets one day, a tank company detached to another division the next. In periods of crisis and highly mobile operations the composition of a combat group could change dramatically. Combat commands were sometimes split into task forces (TFs), identified by the name of the commanding officer.

While armored divisions were organized around combat commands, infantry divisions were generally organized into regimental combat teams (RCTs) with additional mission specific assets attached to a regimental headquarters.

In 1942, Army planners considered the need of doubling the number of divisions to 200—a force considered necessary to defeat the Germans should the Soviet Union succumb to the Nazi onslaught. But as the Red Army endured, American commanders pared back their plans. It is questionable though whether American manpower could have even reached such heights given the crisis in infantry strength that arose in 1944.

The longest duration in a combat zone, 654 days, was accomplished by the 32nd Division in the Pacific, and the shortest, just three days, the 16th Armored in Europe. Pacific divisions averaged 306 days in combat. Some veteran divisions saw action in North Africa, Italy, and Western Europe, the longest periods including the 1st Infantry (443 days), the 3rd Infantry (531 days), and the 1st Armored (360 days).

Ground division casualties totaled about 664,000, not including the Philippine Division. The vast majority were suffered in Europe and the Mediterranean—approximately 570,000. Divisions in the Pacific averaged about 4,700 casualties. The 3rd Infantry suffered the highest casualties with 25,977 in North Africa, Italy, France, and Germany. The 106th Division suffered the highest casualties during the shortest period in combat—8,627 in 63 days, most during the Battle of the Bulge.

The 66th Division suffered 1,452 casualties, although it never reached the front. In response to the crisis in the Ardennes in late 1944, the division crossed the English Channel to Cherbourg on two transports. One, the Leopoldville, was torpedoed by a German U-boat just five miles from Cherbourg with the loss of 14 officers and 748 enlisted men.

The demand for infantrymen in Europe became so critical that some of the late divisions, such as the 70th, 42nd, and 63rd, were so heavily drawn down during the summer of 1944 to provide replacements for combat units that they had to be rebuilt before being shipped to France.

Another major source of manpower in 1944 was the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), instituted to meet wartime demands for junior officers and soldiers with technical skills. Most of the men were trained at colleges in engineering, foreign languages, and medicine.

Opponents of the program, such as General McNair, felt that ASTP took young men with leadership potential away from combat positions where they were most needed, producing a shortage of 300,000 men—the equivalent of over 20 divisions. In 1943-44, manpower planners calculated that additional infantrymen would be required for operations in Europe. The ASTP not only provided well-educated men, it also provided a large pool of ready-trained soldiers. In an emergency measure, in the spring of 1944, about 110,000 ASTP students were transferred to combat units. Some 35 Army divisions received an average of 1,500 men each, some considerably more, such as the 395th Infantry Regiment, 99th Division, which received about 3,000 replacements from the program.

Also in 1944, continued shortfalls in replacing casualties resulted in the use of divisional service troops and Army Service Forces troops as infantry replacements. The mix of divisions by theatre at the end of the war included 60 in Western Europe—four airborne, 15 armored, 41 infantry; seven in Italy—one mountain, one armored, five infantry; and 21 in the Pacific—one airborne, one armored cavalry, 19 infantry.

Some 17 divisions remained in service by June 1946, including the 1st, 3rd, and 9th Infantry and 4th Armored in Germany; the 42nd in Austria; the 88th in Italy; the 6th and 7th in Korea; the 86th in the Philippines; the 24th and 25th Infantry, 1st Cavalry, and 11th Airborne in Japan; and the 2nd and 5th Infantry, 2nd Armored, and 82nd Airborne in the U.S.

The United States Army that fought in World War II was created in a relatively short period and built in a time of crisis. It established the foundation for the future of the modern U.S. Army.

Author Allyn Vannoy has written extensively on a variety of topics related to World War II. He resides in Hillsboro, Oregon.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments