Even in retreat, the German army was formidable. The Allies learned this time and time again on the long road to victory that began in North Africa in late 1942. Following the Battle of Kasserine Pass in February 1943, Field Marshal Erwin Rommel quit the high plateau of the Grand Dorsal in western Tunisia and withdrew to the safety of interior lines in Tunisia. The Germans left behind more than 43,000 mines and demolished more than a dozen bridges to retard the Allied pursuit. A Teller mine could blow the track off any tank or other tracked vehicle. Each mine contained 11 pounds of TNT sealed inside a sheet-metal casing and fitted with a pressure-actuated fuse.

The German armored columns had scored another great victory, this time driving the Allies back 85 miles in less than a week—a much greater retrograde movement than would occur during the Battle of the Bulge two years later. Casualties ran high; the Americans suffered 20 percent losses, more than 6,000 of the 30,000 men engaged in the campaign. A significant portion of the losses were prisoners of war.

In the wake of its tactical defeat at Kasserine Pass, the U.S. Army engaged in a period of introspection and self-flagellation that led to reforms to tactical doctrine, logistics and operations. “We are learning something every day, and in general do not make the same mistake twice,” wrote General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force in North Africa.

After the disaster at Kasserine unfolded in late February, Eisenhower had hurried artillery forward to the threatened sector. He also ordered U.S. II Corps commander Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall to attack Rommel’s exposed flanks, but the II Corps commander lacked the fortitude to undertake a counterattack. Rommel, of course, realized the vulnerability of his own supply lines and pulled back in good order.

The U.S. Army quickly made Fredendall its scapegoat. He deserved plenty of blame, but problems existed higher up the chain beyond his control. In some ways, Fredendall was a typical of many American leaders, but a number of American commanders participating in the battle had shown they had the guts and skill necessary to take on the Germans. Eisenhower sacked Fredendall less than two weeks after the battle. Afraid he might be shot down by the Germans if he flew to Algiers, Fredendall instead rode away from the battlefront in a Buick before boarding a plane for the States.

The Allied command structure was confused. Eisenhower accepted blame for the defeat and vowed immediately afterward to make sweeping reforms. He resolved to subordinate French troops to the Allied chain of command, concentrate American forces when engaging the Germans, issue forceful orders to frontline commanders, and upgrade American antitank capabilities. He had to do all of this while continuing to maintain unity among British, French, and American commanders prone to backbiting. The British directed the frontline forces, given that they fielded 75 percent of the ground forces in the North African theater.

Of course, the Americans needed a commander who understood the tenets of combined-arms operations and did not fight using the tactical principles of the last war. Maj. Gen. George Patton lived and breathed mobile warfare. Patton aimed to shake up the II Corps, and he made good on his promise.

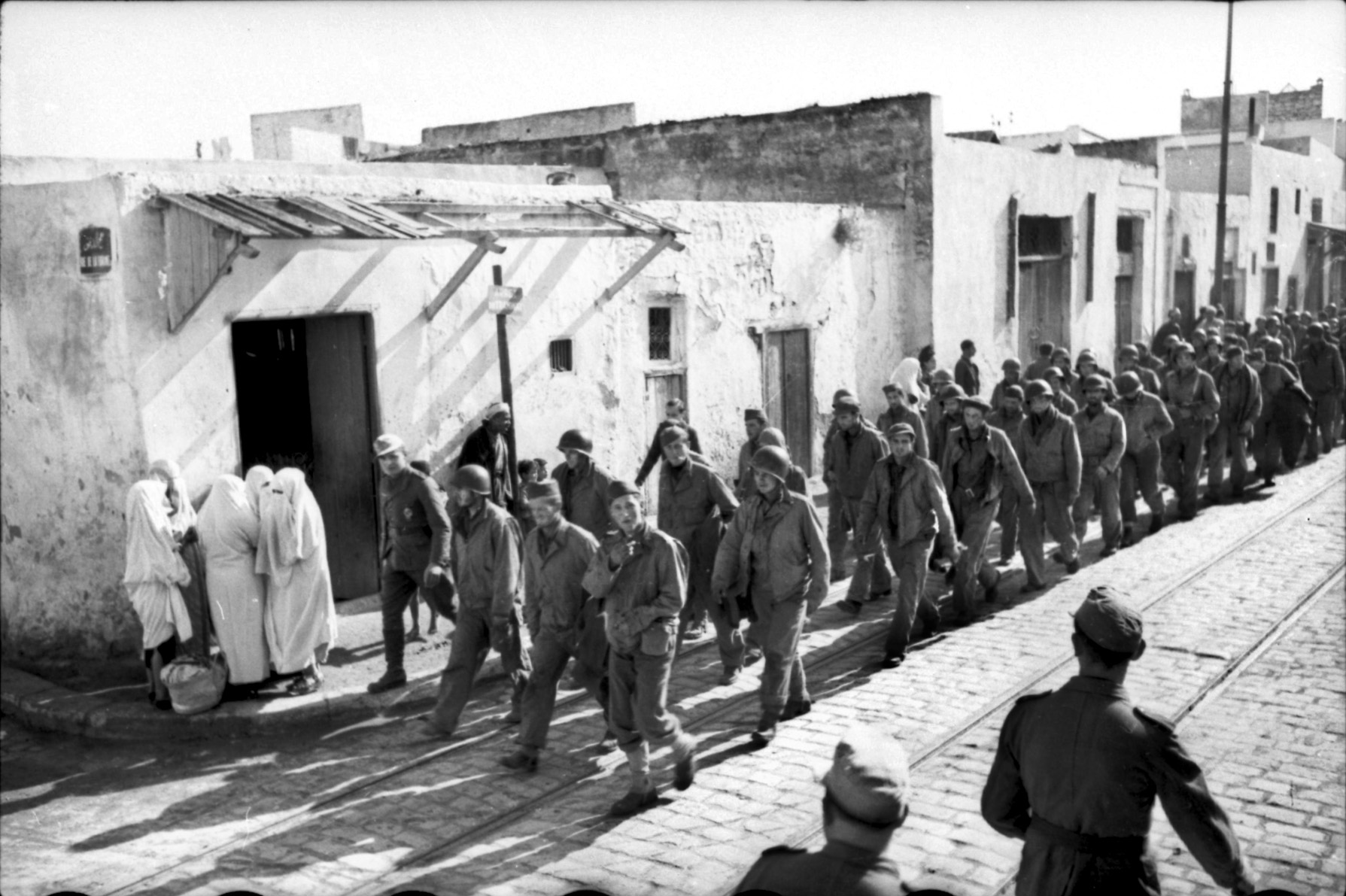

Patton arrived at Djebel Kouif in Algiers on March 7 to take command. In the weeks that followed, he instilled discipline in officers and soldiers alike. The result was a growing sense of esprit de corps in the American fighting forces. He won a quick victory against the Germans at El Guettar, Tunisia, before the month was over. The U.S. First Infantry Division fought extremely well at El Guettar. “The Hun will soon learn to dislike that outfit,” Eisenhower said. The Germans also would come to dislike many other American units.

—William E. Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments