By Alan Davidge

Most of the action during the Battle of Britain in the late summer of 1940 took place over southern England where Royal Air Force Spitfires and Hurricanes began to dominate dogfights against their German rivals. There was also some bombing of British airfields in an attempt to destroy planes on the ground, but on August 24 a few bombs were dropped on London itself, probably by accident as the principal target had been a strategic one.

Prior to this, in May 1940 Britain had itself bombed German communities alongside industrial targets in Mönchengladbach, the Ruhr, and Hamburg, the latter raid killing 34 civilians. At the end of August, during an RAF raid on an armaments factory north of Berlin, some bombs fell on populated areas in the city itself, which provoked an angry response from Hitler; from there the situation escalated.

It was abundantly clear that for many months, the bombing raids conducted by both sides on strategic targets had caused casualties among civilians living nearby as well, but this apparent attack on the German capital seemed to tip the balance. On Saturday, September 7, 1940, Londoners found themselves the target in a war zone.

It began at 5 p.m. after everyone had been enjoying a hot, late summer’s day with temperatures reaching 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The air-raid sirens wailed and many thought it was a false alarm until they heard the drone of the bombers.

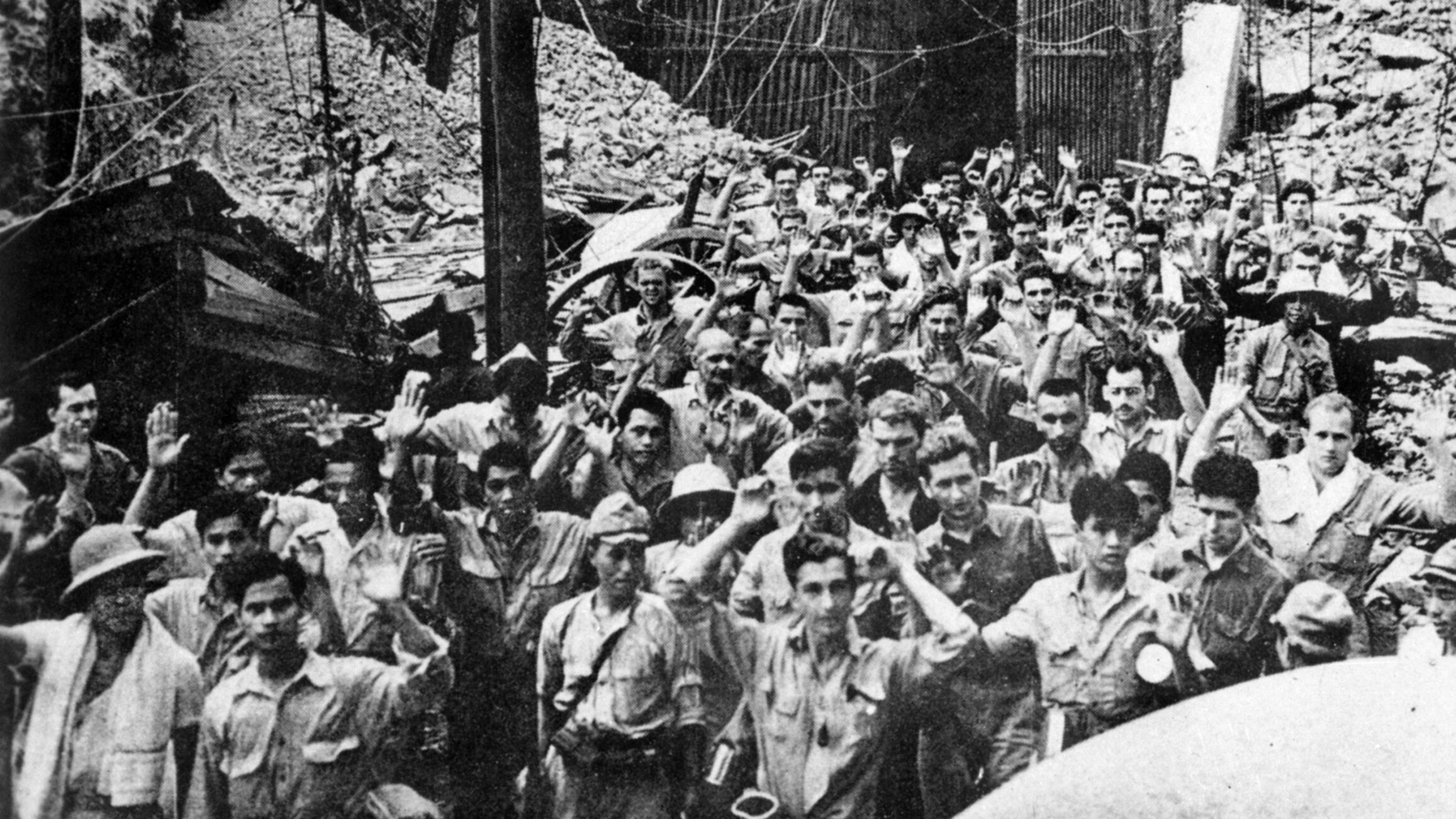

The resistance to Germany so far had been delivered by fit, young men in uniform who understandably expected to endure bombing raids as part of their military duty. They were trained to handle this threat to their lives over a period of time until they were acclimatised to the noise of explosions and understood the effects of blast and concussion.

As servicemen, they were subjected to a rigid discipline which taught them how to react instinctively to an emergency. They had some basic body protection and knew the importance of seeking shelter below ground level to avoid the red hot shrapnel that sped indiscriminately from every explosion and their training gave them the confidence that if they followed instructions, they had a good chance of survival.

They were also issued a weapon with which to fight back, even if its protection was largely psychological. However, those at the receiving end of the bombs on September 7 largely comprised women, children, and those too old or infirm to react quickly and confidently to an attack.

Shelters were already in place for some and these were immediately put to use by anyone who could reach them in time. But nobody really knew what to expect when the bombs exploded and the fires started.

Luftwaffe squadrons of 348 Heinkel He 111 and Dornier Do 17 bombers, escorted by 617 Messerschmitt fighters, had followed the River Thames, which signposted the way up to the docks in London’s East End. As they hurried across southern England, they had already been picked out by the RAF which, although depleted in numbers due to the incessant dogfights over the summer, did its best to take them down.

By the end of the day, RAF pilots had eliminated 33 German planes but lost 28 fighters in the process. A few former naval guns were in place across London but it was only the RAF fighters that scored hits on the enemy. The vast majority of German bombers were to succeed in their mission, dropping predominantly magnesium-filled incendiaries as well as a few high-explosive (HE) bombs on pre-selected targets.

Soon the docks were ablaze, particularly the Surrey Commercial Docks. Cargoes of wood and food supplies that had survived the hazardous journey across the Atlantic menaced by U-boats and German warships went up in smoke. The huge meander of the Thames, comprising much of the borough of Poplar and known locally as the “Isle of Dogs,” was the epicenter of London’s dockland and was a textbook target.

Beckton Gasworks, the largest in Europe, was also hit, as was an oil refinery at the mouth of the Thames and the Ford Motor Works in Dagenham, on the north side of the river. In 1940 most people lived near their place of employment and walked or cycled to work each day, which meant that, although the pilots may have aimed at commercial and strategic targets, their bombs would also rip through the rows of terraced houses that surrounded them.

Dockland was Cockney and working class; few houses had gardens that could accommodate the new brick and corrugated iron Anderson Shelters that had been designed for potential air raids, so families took their chances under the stairs or kitchen table unless they were close enough to the few municipal buildings that were commandeered as public shelters.

At 6:30 p.m. the planes turned tail and headed back from whence they came. Fire crews from the Auxiliary Fire Service, which had been recruiting since 1938 in preparation for raids such as this, continued to fight the flames, in many cases drawing water directly from the river. Families limped home and many packed bags and headed out of London to join relatives in outer suburbs or rural Essex. The glow from the fires was visible 30 miles away.

But it was not over. At around 8:30 p.m., 250 planes returned in menacing waves, this time to discharge 625 tons of high-explosive bombs, containing a lethal concoction of TNT and Amatol, using the fires caused by the earlier incendiaries as a beacon. This two-phase air raid worked well for the bombers and was to become a frequent model for attack over the following months.

Fire boats in the river pumped Thames water at the flames as the paint on their vessels peeled off in the heat. Surrey Docks was a square mile of fire with 1,000 pumps trying to control it.

Further downstream was the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich which stored live ammunition and nitroglycerine. It received several direct hits; the London Metropolitan Archives record 49 deaths from the raid. There was a further attack on the gasworks with HE bombs puncturing gasometers and sending up sheets of flames for the fire crews to deal with.

Among the lesser known heroes that night were the cohorts of teenage boys on bicycles and motor bikes, some as young as 14 who, in the absence of radios for communication, risked their lives acting as runners and message bearers between the central control points and the fire crews.

This second bombing of the docks that night, this time with HE bombs, brought further terror to the families in houses nearby. Those living beside the King George V dock at Woolwich on the north bank of the river were trapped between factories on fire on one side and the docks themselves, and had to run the gauntlet down to the water where they were rowed across to safety.

Also out on the streets in the midst of the inferno were members of the Women’s Voluntary Service, escorting residents out of their damaged houses to organized accommodation in local hospitals for first aid and hot drinks.

When the “All Clear” signal sounded at 5 a.m. on the morning of September 8, the final tally of the night’s casualties was 436 killed and 1,600 seriously injured—all of them civilians who had undergone a baptism of fire as horrific as many of their fathers who signed up to fight in The Great War in 1914. What they could not have imagined in their wildest nightmares was that, with the exception of November 2, they would suffer a further 76 nights of continuous bombing.

Those who survived did not expect that this would be last they saw of the Luftwaffe. Even in the lulls between the raids, many London residents woke up to find an unexploded bomb (UXB) in their back yard, which would have to be made safe in case the next raid set it off.

Residents near the Beckton Gasworks had noticed several bombs fall harmlessly in the spoil heaps along the perimeter, known locally as the Beckton Alps. (In the 1980s, after the closure of the gasworks, it was announced that this part of the site would be developed as an artificial ski slope, much to the concern of the locals with long memories!)

Survival of the night was not always an automatic reward for those who followed safety instructions. Often the opposite happened. Tom Betts, aged 12 and the eldest in his family, was expected to look after his mother after his father joined the RAF. As soon as the second bombing raid started, he insisted that they leave their flat for the official shelter under Columbia Road Market in Bethnal Green, believing it offered greater protection for his mother and himself.

He even found a place by a ventilation shaft to give them some air. Unfortunately a German bomb found the shaft as well, a million to one chance as the opening only measured three feet by one foot. Young Tom woke up in hospital with a serious head wound—and the terrible news that his mother had been killed, along with 39 others.

Tom Winter, aged 11, and his three younger siblings had been separated from their mother between the raids and when the bombing started again, he decided to hurry them along to a Refuge Centre, set up for displaced persons at Keetons Road School, Bermondsey, on the south side of the river.

A neighbor and friend of their mother spotted them and took them in, believing that they would be more distressed in the shelter surrounded by adults that they didn’t know. This act of kindness saved them from death or serious injury because, like Columbia Road Market, the school also took a direct hit, killing 38 who had sought safety there.

The next morning, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, knowing instinctively that spirits had to be kept high, visited bomb sites all over the East End while surrounded by journalists. The response was encouraging and the papers reported what was heard: “It was good of you to come, Winnie. We can take it, give it back!”

Publicly, Churchill promised “Repayment with compound interest,” meaning he would order attacks on German cities. But what the public wanted to see was retaliatory action in their own skies.

The following night, September 8, the bombers returned, 200 of them, hitting the docks again and following the Thames upriver to the city itself. Offices, factories and railway lines were targeted, but the Londoners themselves suffered most, sustaining over a thousand casualties including 412 deaths.

On Monday September 9, the raids lasted ten hours, killing 370 people and injuring 1,400. South Hallsville School in the East End, which was used as a Rest Centre, took a direct hit, resulting in hundreds of casualties.

Entertainment venues in the affluent West End were also destroyed, and a bomb at the Holborn Empire put an end to nightly revues by the recently christened “Forces’ Sweetheart,” Vera Lynn and risqué comedian Max Miller, “The Cheeky Chappie.”

Undeterred, Vera drove through London’s streets in her canvas-topped Austin 10 cabriolet, wearing her “tin hat” to new venues where her songs could help Londoners forget their nightmares for a while.

In these first few days of the Blitz, Londoners voiced the opinion that the government was not doing enough to fight back. One reason was that, during the first daytime air raids, gun crews were told not to fire unless they had a clear view of the target, for fear of hitting a friendly Spitfire or Hurricane that was also trying to bring down the bombers.

Churchill knew that he had to raise morale and, having just witnessed the capitulation of France under similar pressure, and knowing that there were still some in government who favored an armistice, he had to take action.

Furthermore, the first night of bombing had seen large numbers of people packing their bags and leaving the capital. If such an exodus continued, it could have disastrous consequences.

All the victims of the raids agreed that the sound of their own gunfire was what most helped them to feel safe—and they wanted to hear more of it. However, this was not as simple as it sounded. Although London had suffered air raids during World War I, with Zeppelin airships and Gotha bombers flying from occupied Belgium bringing terror to the civilian population, its guns had not provided a satisfactory means of defense against them.

The former naval and artillery pieces positioned around the capital were never designed for shooting down aircraft and, despite sounding impressive and reassuring, they were totally ineffective. Worse than that, their own returning shells were responsible for the deaths of large numbers of the population. The government was aware of this but it was kept from the media because of its likely effect on public confidence and morale.

After 1918 the guns were all removed and it was hoped that this tragic experience would never have to be repeated. In 1932 British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin commented, “It is important for the man in the street to realize that there is no power on earth that can protect him from bombing, whatever people may tell him. The bomber will always get through.”

It was becoming clear that, in a future war, the only effective strategy would be to take the fight to the enemy and bomb their cities and strategic targets harder than they were bombing our own. This would create a war of attrition like WWI trench warfare, but this time civilians would bear the brunt.

Writing in 1938, the British scientist and former WWI officer, J.B.S. Haldane estimated that in many World War I air raids, falling anti-aircraft shells had killed almost as many people as German bombs.

The first reason was unreliable fuzes. Clockwork timers were in their early stages of development and the traditional gunpowder or igniferous fuze often took longer to burn if fired to heights where oxygen levels were lower. The mass production of shells in wartime often resulted in poor quality control and “dud” shells.

The net result was heavy, live shells plummeting to earth at nearly 200 mph. If they exploded they could be just as deadly as a bomb. (Today, visitors to well-preserved European warscapes such as the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc in Normandy that were both bombed and shelled will see a cratered terrain where it is impossible to determine whether the deep depressions which still survive were the result of an air raid or naval bombardment.)

The former naval guns positioned around London as protection during the Blitz would have been perfectly effective in their previous role at sea; if they missed their target, their shells fell harmlessly into the water but these were coming back to earth! Even the shells that fell on the city without exploding could still be deadly, and the remains of those which worked correctly and exploded several thousand feet in the air would arrive at ground level as lethal, red-hot shards of metal.

The ultimate decisions on defense against the bombers were Churchill’s. Ironically, he had opposed the use of artillery in WWI for this purpose. It was ineffective even against the gas-filled Zeppelins and primitive biplanes and, in his words, the guns were simply “Instruments of self-destruction.”

But the people wanted more guns whose elevated cacophony each night would make them feel that they were “giving it back,” so the government gave them their guns knowing full well that the price of higher morale would be greater damage and pain.

By the evening of September 10, twice as many artillery pieces were defending London than on September 7. They had been moved from other strategic emplacements, and by the following night the RAF would disappear from the night skies to give them full rein in dealing with the predators.

The guns from now on would unleash a continuous barrage without the trouble of taking aim and, with only 11 gunlaying radar units at their disposal, there could be no effective guarantees of accuracy. The searchlights in place also did little to help, as their range was no higher than 12,000 feet.

On Wednesday, September 11, every gun barrel around London, an area of almost 200 square miles, was pointed skywards, firing continuously, and the Daily Express later celebrated “Gunfire louder than the bombs.” Thirteen thousand shells were expended, but not a single plane was hit.

This firestorm did succeed in unnerving the German pilots, however, and their response on this and subsequent nights was less caution in selecting their targets in favor of an early exit. Many Londoners then caught a jettisoned bombload that had been intended for an industrial site several miles away.

Those who had made the decisions to increase the artillery bombardment, irrespective of the consequences at ground level, soon found shells arriving in their own back yards, literally. On September 11 there was a direct hit from an anti-aircraft shell on Westminster Abbey while another struck the House of Lords, followed by more shells hitting the House of Commons library and Horse Guards Avenue, causing several casualties.

On September 13, No. 10 Downing Street, the official home of the British prime minister, was damaged; four days later, the building’s own air-raid shelter was hit.

It was later calculated by General Frederick Pile, in charge of Air Raid Precautions (ARP) that, during 1940, it took 20,000 shells to shoot down one plane. Work done at the Cavendish Laboratories in Cambridge on the fuzes used in British shells at the outbreak of the war suggests that up to 50 percent could have been defective.

Even if this is a gross over-estimate, the damage done by a significant proportion of these shells, weighing on average 30 lbs., exploding on the ground or hitting buildings, would be the equivalent of many additional bombing raids.

The progress of the raids upriver meant that the city’s most historic buildings were now under threat. These were as close to the heart of the Londoner as they were to the heart of London itself, and losing them would would be emotionally devastating.

Perhaps the most iconic during the Blitz was St. Paul’s Cathedral, whose dome dominated the skyline throughout the bombing. On September 12 it had its first of many close shaves when a very large bomb, believed to be 2,000 kg, buried itself eight meters below Dean’s Yard on one side of the cathedral.

Lieutenant Robert Davies led a team that spent three days clearing a path through fractured gas mains and electricity cables to remove the bomb as it could not be defused. It required two lorries to pull it out, and Davies then drove it without assistance along bumpy, cratered streets to Hackney Marshes in the East End. This area had been already chosen as the safest place for controlled detonation of ordnance, becoming London’s “bomb cemetery.”

When the dust settled after he had pushed the button, a 100-foot crater was revealed. It would have meant the end of St. Paul’s. For his bravery in destroying this monster, Davies became the second person in Britain to be awarded the George Cross—a medal instituted by King George VI for conspicuous gallantry on the home front, equivalent to the Victoria Cross on the battlefield.

After the first few nights it was clear the pain was being spread further across London, and on September 13 Buckingham Palace was hit. Queen Elizabeth (mother of the current queen) was quoted as saying, “I’m glad we have been bombed. It makes me feel I can look the East End in the face.”

Newsreels and daily papers carried features of the Queen and King George VI the next day visiting families near the docks and sharing their experiences of attacks by the Luftwaffe, although the more cynical of the Cockneys were quick to point out that they still had one or two palaces in reserve if they lost their primary place of residence.

As the threat to their homes increased, Londoners became very inventive in finding shelter during the air raids. London was rich in underground protection because of its “Tube” railway system but the government had expressly forbidden the stations to be used for this purpose.

On the night of September 19 the public decided to take matters into its own hands and began arriving at the stations as soon as the rush hour ended, with bags and blankets, ready to stake their pitch on the platforms. This became the norm and the government had to concede, eventually improving facilities to take account of this change to the stations’ original functions.

A public shelter was created at Aldwych near the center of the city and flood gates were placed in tunnels that led under the River Thames; 79 stations were fitted with bunks for 22,000 people and 124 canteens were established within the Tube system.

Lord Woolton, appointed originally by former Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain as Food Minister, took further decisive action, allocating 144 vehicles, staffed by volunteers to take in food relief after air raids and “food trains,” which ran in the underground 7-9 a.m. and 5-7 p.m.

Woolton’s intuitive actions on the provision of food where it was most needed played an important role in maintaining morale. When he was promoted to Minister of Reconstruction in 1943, Canada’s Montreal Gazette wrote, “The famous British morale can be credited as much to Lord Woolton as to any individual.”

The people had spoken and the government had listened. It was a further boost to morale that Londoners did not have to fight authority as well as the Germans. The decision to allow the use of tube stations as shelters was to save many lives but it was not foolproof.

The following month, in south London, a bomb penetrated the road and tunnel at Balham station, smashing water and sewage pipes and killing 66 people who were sheltering there. Bank station in the financial center later received a direct hit from a huge bomb and the 100-foot crater collapsed on those below, killing 56.

Taking stock of the situation towards the end of September 1940, Londoners had gone, within the space of a couple of weeks, from enjoying the freedom to bask outside in prolonged summer weather to sheltering in corners through bombardments which lasted for hours, depriving them of their sleep, and not knowing whether the next day would be their last.

Nothing in their lives had prepared them for this, but they could not give in because the bombing campaign was very likely a prelude to an invasion. Furthermore, many had a job to do that would help to stop Hitler. Factory workers had transferred to the munitions production line at Silvertown, seamstresses had become welders, and the former car factories were now turning out Hurricanes and Spitfires.

If they ran away from London, they would be letting down the men who must be kept supplied with the necessary weapons to fight the enemy. They were not trained soldiers, but they were the front line, indeed the last line, in a war that would determine how they, and future generations would live.

Londoners were in no position to devise a long term strategy; they just had to survive from day to day. All that they had to embolden them was the sound of their own guns at night and speeches or songs from the BBC radio broadcasts between the sounds of the explosions.

In the community shelters they sometimes sang their way through the bombing, often using specially adapted versions of current hits like “Run, Rabbit, Run” which became:

Run, Adolf, run Adolf, run run run

You were the starter who fired the gun,

then taking aim at his henchmen:

We will knock the stuffing out of you,

Old fat Göring and Goebbels, too

and finishing with:

So cut your loss and pawn your Iron Cross,

Run, Adolf, run Adolf, run run run!

The bombers came back every night in varying numbers. On October 6 there were only seven of them, but on October 15, 380 bombers hit London, killing 200 and injuring 2,000.

The tactics varied nightly as well, as did the bomb load. The Luftwaffe began to realize that the tall city buildings cushioned some of the HE blast, so they experimented with the “parachute mine,” which came down slowly and detonated above the ground, creating deadly shock waves and shooting metal fragments in all directions.

It was a parachute mine on the night of April 17, 1941, that was to kill the celebrated singer Al Bowlly in his London flat after he had returned from a singing engagement. Like many victims of this weapon, he suffered a fatal injury caused by the actual blast generated by the explosion which blew a door off its hinges, delivering a serious head wound. He was buried in a mass grave with other casualties of the night’s bombing.

Another change in strategy was the switch to “night only” bombing, commencing on October 7; in addition to the Dorniers and Heinkels, Junkers Ju 88s joined in the raids. It is significant that all the bombers were medium, twin engined planes. Germany never developed a four-engined heavy bomber, which could be seen as a serious missed opportunity, considering the damage that was done later in the war to Germany by machines like the Avro Lancaster and Boeing B-17.

In addition, there was no specific strategy to target particular industries such as aircraft manufacture, which could have brought Britain to its knees. There was also inadequate intelligence on British industry because Hitler did not believe that the two countries would actually go to war with each other until the early part of 1938.

The result was more of a scatter-gun approach to bombing which, although painful, was survivable. If the Luftwaffe had concentrated on taking out one particular industry and then moving on to another, they could have used their resources to devastating effect.

A further strategic move in November was to extend the attacks to other large industrial cities such as Birmingham and Manchester, while continuing to bomb London. In one of the worst nights of bombing, on November 14 the center of Coventry in the Midlands was almost completely destroyed, while port cities such as Liverpool, Bristol, Southampton, Plymouth, and Glasgow suffered treatment similar to the London docks.

Any criticisms of Luftwaffe strategy would be completely academic to those at the receiving end, who only knew that they were being bombed every night. Londoners were, however, finding ways to cope and, as well as occupying the local tube stations and sharing the public shelters, many were soon taking advantage of the new cage-style “Morrison” shelter which could be constructed in their own home.

Its steel top, which doubled as a table, was built to withstand the collapse of the upper half of a two-story house. These were to function well and reduced the death rate considerably.

The London shelters were put to a major test on December 29 during a night that was referred to as the second “Great Fire of London” by a U.S. reporter cabling an account back to his office. (The original Great Fire was in 1666 when most buildings were constructed of wood).

A total of 136 bombers attacked the city, focusing on non-residential buildings but still managing to kill 60 civilians and injure 250; 120 tons of HE bombs and 22,000 incendiaries fell that night on the city, creating 1,500 recorded fires.

On this occasion, the principal water main was fractured and the Thames was at low tide, making it much harder for fire crews. St. Paul’s Cathedral was hit by 28 incendiaries, causing the lead on its dome to melt.

Churchill was aware of the value to morale in keeping this iconic building safe and had allocated more staff on site who managed to keep the fires under control. The American war correspondent Ernie Pyle reported:

“Into the dark shadowed spaces below us, while we watched, whole batches of incendiary bombs fell. We saw two dozen go off in two seconds. They flashed terrifically, then quickly simmered down to pin points of dazzling white, burning ferociously…

“The greatest of all the fires was directly in front of us. Flames seemed to whip hundreds of feet into the air. Pinkish-white smoke ballooned upward in a great cloud, and out of this cloud there gradually took shape—so faintly at first that we weren’t sure we saw correctly—the gigantic dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

“St. Paul’s was surrounded by fire, but it came through. It stood there in its enormous proportions—growing slowly clearer and clearer, the way objects take shape at dawn. It was like a picture of some miraculous figure that appears before peace-hungry soldiers on a battlefield.”

By the start of 1941, it was clear that the regularity of air raids was decreasing, but that did not mean that there would be any slackening of their intensity when they did arrive.

By March 8, Londoners had enjoyed almost two raid-free months, but that was to soon change. Overnight, several railway stations and Buckingham Palace became victims of 30,000 incendiaries. The West End’s entertainment district, which had become popular once again, suffered badly, and the restaurant at the Café de Paris, located 20 feet below ground and regarded as one of the safest places to eat in London, was devastated by a stick of HE bombs that fell across Leicester Square. Thirty-four people were killed, among them the popular bandleader, Ken “Snakehips” Johnson, another contemporary of Al Bowlly who had regularly sung with the band.

On March 15, southeast London was carpeted with 100 tons of HE and 16,000 incendiaries. Four nights later, 500 planes dropped 470 tons of HE, including “Maxes” (5,500-lb. bombs) and 122,000 incendiaries, plus a large number of parachute bombs. One East End public shelter in Poplar was hit, killing 44 people.

A month later on April 16, the city was subjected to a seven-hour blitz which was remembered as being the worst since September 7 of the previous year. Then, on the 19th, 1,000 tons of HE were dropped on the city, together with 150,000 incendiaries. Again the docks suffered, all the way from Tower Bridge, to Greenwich where the prestigious naval college was amongst the casualties.

Saturday evening, May 10, saw London’s population in high spirits after the conclusion of the soccer cup final at Wembley Stadium, watched by nearly 100,000 spectators, as merry as they had been on the sunny Saturday afternoon of September 7 the previous year.

But by 11 p.m. on that clear, cloudless night, the sirens were wailing again, signalling the approach of 507 German bombers that dropped their loads, flew home, and then returned to deliver more punishment.

The night’s events began to stir painful memories of September 7, but it would prove to be even worse. Dockland was once again the main target and both sides of the Thames were soon alight from the first of the docks all the way up to the city; 2,154 fires were actually recorded, but they soon joined up to form giant conflagrations across London, causing damage to many historic public buildings.

These included the Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, St. James Palace, the Tower of London, the British Museum, Public Record Office, and the Law Courts, as well as many centuries-old guild halls, railway termini, and churches. Once again, fractured water mains and low water in the river made it impossible for the fire brigades to contain the inferno.

The All Clear did not sound until after 5 a.m. on May 11, by which time the capital had been the recipient of 711 tons of high explosive and over 86,000 incendiaries. The human cost was 1,436 dead and 1,800 seriously injured. Eleven thousand houses were damaged beyond repair and over 12,000 people were homeless. It had been the worst night of the Blitz.

Once the bombing had finished, there was another problem to be dealt with: what to do with the rubble and the bomb sites. Ever resourceful, the government decided to shift the debris to provide runways for the new airfields being constructed in the eastern part of the country that pointed towards Germany. (The rubble from the city of Birmingham built the airfields that were later to be used by the U.S. Air Force.) The spaces that were cleared were then turned into “Victory Gardens” to help feed the population that Hitler was trying to starve into submission.

Effectively, the London Blitz as such ended on the morning of May 11. At the time, especially in London after the night that they had just suffered, it could not have felt like a major turning point in the war. But it was.

Back in September 1940, Britain had been at its weakest and the future of Europe rested on its shoulders. If the power of the German bombing had scattered London’s population out of the city, it would have been the start of an economic and social collapse. Instead, the people rolled with the punches until they had a lucky break which, in this case, was Hitler’s declaration of war on Russia in June 1941.

This act was to consume, increasingly, vast amounts of Germany’s resources, particularly its bombers that would ease the pressure on Britain. The population of London, with no weapon with which to fight back, except its obstinacy, had turned the war. By the end of 1941 Britain had the United States as an ally, their factories were still turning out war materials, and they still had enough food to survive.

The future was still uncertain, and would remain so until the defeat of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Korps nine months later in October 1942 at El Alamein gave them some hope.

The citizens of the capital knew they could not afford to be complacent when the bombing appeared to stop. They were still painfully aware that the U-boat attacks on the Atlantic convoys could still deny them valuable food and equipment, but they would, however, be able to work longer days and nights to help the war effort.

There was some relief when news came through of daring commando raids against the Germans in Norway, but irregular attacks on other cities, especially seaports, were a reminder that further raids were possible on London.

In addition, the “Baedeker Raids” in April and May of 1942 caused considerable damage to historic cities such as York and Bath. There were also many false alarms.

Tragically, the worst loss of life associated with the air raids took place without a bomb being dropped. On the night of March 3, 1943, the sirens sounded in the East End, causing a large number of people to hurry down the steps of Bethnal Green tube station. A woman and child lost their footing at the base of the steps and those behind them fell forward resulting in 173 deaths by asphyxiation—mostly women and children.

The increase, in following years, of Bomber Command attacks on German industrial cities eventually prompted retaliation and, in January 1944, the Luftwaffe launched Operation Steinbock, nonchalantly referred to by Londoners as the “Baby Blitz.” Raids were nowhere near as intense as in 1940/41 and the campaign ended in May of that year.

It achieved very little but resulted in the loss of 329 German planes, mostly shot down by the new Mosquito and Beaufighter fighter-bombers. This was to prove particularly costly as it meant that the Luftwaffe was to have fewer resources with which to rely for repelling the

Allied invasion of Europe on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

The arrival of the V1 flying bombs or “Doodlebugs,” commencing June 13, 1944, brought the terror back to the streets of London, forcing its population to dig deep into its personal reserves once again.

Over 6,000 deaths resulted from V1 attacks and initially there was an exodus from the city which threatened to affect industrial production, but the Allies were now in Europe, taking the fight back to the enemy, which inspired hope that it would soon be all over.

However, Hitler had one more terror weapon in his arsenal, the V2 rocket, which arrived without warning at supersonic speed. The V2 campaign lasted from September 1944 to March 1945, killing over 2,700 people and injuring 6,500.

Had the V1s and V2s been developed earlier, it is difficult to imagine how the population could have stood up to them but, having coped with the Blitz, and knowing that the war could not go on much longer, Londoners steeled themselves and took the extra punishment, hanging on to the bitter end.

Much has been written to try and understand how Londoners coped during the Blitz, and some of it by the participants themselves. “Mass Observation,” a national project, begun in 1937 by several authors including a social anthropologist from Cambridge University, invited the public to keep a daily diary of their experiences and feelings, as well as the contents of relevant conversations they were party to. Initially, it reflected how society in general was changing in the build up to war but the most valuable material comes from the period after the Blitz began.

The “Phoney War” experienced since September 1939 had caused many evacuees to return to the capital because it had not been affected as badly as they expected and they were prepared to put up with the blackouts, rationing, and queuing if it meant being back home.

September 7 changed all that, forcing them to get used to the fear of violent death and seeing it manifest itself every day. Many volunteered for work that made their lives even more precarious. In addition to the 6,000 regular firemen and the 60,000 auxiliaries, were tens of thousands of part timers—men and women who had full-time jobs as well.

As well as helping the fire service, people volunteered to work as Air Raid Precaution (ARP) wardens, ambulance drivers, medics, telephonists and messengers. After a serious incendiary raid on London on September 29, compulsory firewatching was also introduced: all men (and later, women) aged 16-60 were required to donate 48 hours of their time each month.

Next to the actual bombs, the biggest threat to health was sleep deprivation. Anderson shelters were cold, damp, and cramped places to try and spend a night, but they enabled families to stay together. Tube stations and communal street shelters were squalid, initially without any facilities, and frequently overcrowded.

Considering these options, some Londoners resorted to “Trekking”—getting away from the built-up areas to the nearest woodland and sleeping rough; but few managed to maintain this way of life. Those who had to go to work after a miserable night’s sleep soon found themselves near breaking point the next day as the pressure to increase output did not slacken.

Families who were “bombed out” were sent to Rest Centres such as church halls; when the sirens went, they had no alternative but to use the communal shelters. They had lost their Anderson or Morrison as well as their house.

With such a tenuous hold on life, superstition began to play a more important role than before for many people. The Tower of London, dating from 1086, had always been home to a flock of ravens. The legend attached to them is that if they should die or leave the Tower, England would fall. In the early part of the Blitz all but three were killed or died of stress, so Churchill, quick to see the threat to morale, took immediate steps to top up the flock.

At the individual level there were often rituals to be observed before entering the shelter. Women ensured they were wearing a clean pair of knickers in case they “copped a packet” and ended up in the hospital and families delayed entering their Anderson until lucky charms and mascots could be found; even then there would be portents to look out for.

The author’s grandmother, Frances Elizabeth, a pub landlady in the East End and regular participant in games of chance among the local Chinese community in Limehouse, had managed the Spotted Dog in Poplar. She was lucky not be be there when a bomb demolished it in October 1940. The following year after an air raid, she returned to her house in East Ham to find a tombstone from a local cemetery had been blown through the roof and onto her son Joe’s bed.

She took this as a harbinger of the worst possible news, especially when, several months later, she received a telegram that he was “missing, believed captured.” Fortunately, by this time he was safe in an Italian POW camp overlooking the Bay of Naples.

It is estimated that around 40,000 people died in the Blitz and three times that number were injured.

Forecasts by psychiatrists before the Blitz predicted that hysteria, panic and despair would overwhelm the population but after the initial shocks, a determination to survive took over. The U.S. military attaché, General Raymond E. Lee, remarked after a month of the Blitz “The British are stronger and in a better position than they were at the beginning.”

The U.S. Ambassador, John G. Winant commended “the effort made to maintain the appearance of normal life in the face of danger and the acceptance of hardships and hazards by ordinary people.”

This attitude was supported by a more objective Gallup survey in October 1940 which calculated that 80 percent of the public felt it was impossible for Hitler to win the war by air raids alone and 89 percent were solidly behind Churchill’s leadership.

The government had also expected a flood of mental-health breakdowns, but by December 1940 its surveys showed that the number of “Civilian Neuroses” admitted to psychiatric hospitals was just 25 in London and three for the rest of the country. In February 1941, five months into the Blitz, “Nervous shock” comprised only 5 percent of air-raid casualties, most recovering within two weeks.

It was deduced from subsequent investigation that those who were most severely traumatized had left the city after the first few days and the ones who hung on managed to find a hidden determination that saw them through to the end.

Not all Londoners covered themselves in glory. Those who had lived off petty crime before the war had a field day during the Blitz. The London police, stretched to their limits by the nightly bombings, now found themselves facing a new crime wave.

One of the most notorious was a Cockney known as “Mad Frankie” Frazer who, like a number of his contemporaries, burned his conscription papers and disappeared into the underworld. The air-raid siren was his call to work. When the bombs smashed, Mad Frankie grabbed. Jewellers and furriers were favorites, especially in London’s West End, but any opportunity for looting was welcomed. Frankie and the Luftwaffe made a perfect team.

Thefts gave rise to a flourishing Black Market in London and before long, armed gangs were controlling the show. Many criminals who spent their afternoons in darkened cinemas with George Raft, James Cagney, and Edward G. Robinson for company now fancied themselves as real gangsters and began seeking out army bases from which handguns could be traded for their ill-gotten gains.

However, although anyone caught in the act of stealing from fellow citizens could often be subjected to some rough justice, Londoners did find themselves ambivalent to anything offered on the “black market” at times of food shortages and when essentials were rationed.

When the war eventually ended, it seemed to the Blitz survivors from what they had heard from the national media that the great turning points at El Alamein, D-Day, and Monte Cassino and the dashing raids like the “Dam Busters” or St. Nazaire were what deserved the greatest credit.

Their passive resistance in the dark days of 1940/41 could not warrant the glory that belonged to the battlefield heroes—despite the fact that many had earned their “red badge of courage” and several had been awarded the George Cross for outstanding acts of bravery on the Home Front.

For most of the population, the priority was simply to pick up the pieces, welcome home their heroes and resume family life. The government they elected in 1945 was aware of their needs, however and began rewarding their stoicism with a program of social and economic reform that helped them to rebuild their lives.

Prefabricated temporary houses (“Prefabs”) were assembled at great speed while local councils built new dwellings containing modern amenities. The 1947 New Towns Act provided for the construction of eight new towns around London, many of which provided a final destination for nomadic Blitz victims.

At the same time, a new National Health Service was created, providing support from “the Cradle to the Grave” in an attempt to make the remainder of their lives more bearable. As a bonus, they also found themselves among the recipients of the three billion U.S. dollars provided by the Marshall Aid Plan for the reconstruction of Europe.

There may have been a tendency subsequently to glamorize the Blitz, but for most of those directly involved there was no nostalgia, just a desire to try and forget what they had been put through and hope it never happened again.

Nevertheless, there would be moments in years to come after newspapers carried stories of the failure of others to cope with hardships elsewhere in the world, or even in Britain within the next generation, that generated a satisfying nudge and a wink among the Londoners, signifying that when their bugle had called, they had not been afraid to rise to the occasion, hold the line and treat the enemy with the contempt it deserved.

A frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly, Alan Davidge lives in Normandy, France.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments