By William H. Langenberg

As an effective naval weapon, submarines were in their infancy when World War I began in August 1914. This condition was soon to change, as German U-boats quickly scored impressive victories at sea. The most significant of these took place off the west coast of Holland on September 22, 1914. On that fateful morning, Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen, skipper of U-9, became an instant war hero when his primitive submarine torpedoed and sank three British armored cruisers, HMS Hogue, Aboukir, and Cressy, in a single battle that lasted only 95 minutes. That incident shocked the British Admiralty and public, while concurrently sparking great pride in Germany. Perhaps more importantly, it clearly signaled to the world that the technology of warfare had advanced significantly. The submarine had suddenly and dramatically come of age.

Despite the early success of U-9 attacking warships, the British Admiralty initially doubted that Germany could conduct an effective submarine war against merchant shipping. This belief was based on then existing international law and the inherent design limitations of early submarines for antishipping operations under these perceived legal restrictions. The relevant international law was the 1909 Declaration of London, drawn up by major maritime nations, including Germany, Britain, and the United States. The resulting 71 articles created an international body of admiralty law, which was incorporated into each participant’s code of naval conduct called Prize Regulations.

In essence, these regulations allowed belligerent warships to stop any merchant vessel at sea, then board and search it for contraband. If contraband cargoes were found, the offending vessel could be seized and sent to port under a prize crew. In the event the warship could not do that for any reason, the vessel carrying contraband could be sunk. The sinking, however, was not to take place before “all persons on board had been placed in safety.” For a small, primitive submarine, taking the target vessel’s crew on board was impossible. Hence, the ship was normally sunk by gunfire or scuttling after its crew had abandoned ship in lifeboats. Throughout this entire boarding and inspection process, the submarine was normally required to remain on the surface, vulnerable and exposed. The hunter could easily become the hunted. A single hostile shell could damage the submarine or send it to the bottom.

As World War I unfolded, submarines on both sides became bigger and more formidable weapons of war. Large deck guns were mounted on most new boats, and powerful diesel engines for surface cruising greatly extended their range. As long as both sides complied with the Prize Regulations, however, submarine attacks against merchant shipping usually required the attacking submarine to surface and remain in the vicinity of the stopped vessel until the requisite inspections of cargo and registration documents were completed. Given this expected modus operandi by German U-boats, the British Admiralty conceived a secret, imaginative plan to destroy those that could be lured to the surface, close to their presumed prey.

This secret plan, variously named the special service, decoy, mystery, or Q-ship program, was conceived by the Admiralty near the close of 1914. To implement the concept, the Admiralty acquired a diverse group of merchant steamships and fishing vessels and armed them with a variety of quick-firing guns, concealed behind easily removed false shielding. They were manned mostly by Royal Navy personnel and sailed into known U-boat operating areas as seemingly innocuous merchant vessels flying neutral colors. This was permissible under the restrictions of the Prize Regulations, providing the Q-ship lowered her neutral flag and hoisted the British ensign before opening fire.

As the war progressed, Q-ship operations and defenses became more sophisticated on both sides. Expanded Q-ship manning permitted “panic parties” to take to the lifeboats when a German U-boat approached on the surface with hostile intent, while the gun crews remained concealed at their battle stations. Some Q-ships acquired heavier guns and launching facilities for depth charges and torpedoes. In addition, their holds were sometimes filled with timber or empty steel drums so that the vessels could remain afloat after being struck by a torpedo. German submarines that escaped from Q-ship entrapments quickly spread news of this secret threat, generating increasing caution among other U-boat skippers before they approached possible decoy ships on the surface.

After February 1917, when Germany abandoned the Prize Regulations to adopt unrestricted submarine warfare and the British reinstated the convoy system, the efficacy of Q-ships sharply diminished. Merchant vessels could now be sunk by torpedoes fired from submerged U-boats, with no prior warning. Seemingly innocuous Q-ship merchant vessels, steaming independently of convoys, aroused immediate suspicion among U-boat commanders.

Because of the secrecy surrounding the British Q-ship program throughout and even long after World War I, information regarding its success, as measured by U-boat kills versus Q-ship losses, remains nebulous and conflicting. It appears that about 15 U-boat losses can be directly attributed to Q-ships, while perhaps 38 Q-ships were sunk by submarines, 17 in 1917 alone after unrestricted submarine warfare commenced. The postwar consensus seemed to be that the Q-ship program would be foolhardy against an enemy employing unrestricted submarine warfare, especially if the submarine’s normal targets were known to sail in convoys protected by escort warships.

The December 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor immediately drew America into World War II, which had been raging in Europe for over two years. Despite prior threats of involvement, the United States was not prepared for war when it came. This quickly became evident in the Atlantic Ocean off the U.S. East Coast when Germany launched its unrestricted submarine offensive Paukenschlag (Operation Drumbeat). U-boat sinkings of U.S. merchant vessels, particularly tankers, began in earnest during early January 1942.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt had served from 1913-1920 as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the Woodrow Wilson administration. This assignment had provided him with considerable knowledge and experience with the U.S. Navy’s missions and capabilities, a background that, combined with his natural self-assurance, sometimes led him to intervene in naval affairs. Thus, it is understandable that on January 19, 1942, as the devastating effects of Paukenschlag were first being evidenced, Roosevelt suggested to COMINCH (Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet), Admiral Ernest J. King, that deploying American Q-ships might have some value, since the young German U-boat skippers would have no experience combating the program. Admiral King, with some misgivings, perceived this suggestion to be a directive, and immediately took action to implement it.

Thus the American Q-ship program of World War II, highly classified Project LQ, was created and assigned to the Commander Eastern Sea Frontier (CESF) for execution. Two weeks later, CESF suggested that since many U-boat attacks were being made at night against tankers, that type of vessel might be a logical choice for a Q-ship. He also recommended a second vessel “of such relatively insignificant appearance that upon sighting it a submarine would not submerge.” Both suggestions were promptly approved.

Meanwhile, COMINCH had procured three other vessels for conversion: a Boston-based fishing trawler and two steam-powered cargo vessels. These five diverse ships now became the backbone of the U.S. Navy’s highly secret WW II Project LQ, the reincarnated Q-ship program. Funding for Project LQ was also highly classified. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral H.S. Stark, opened a special account at Riggs National Bank in Washington. Access to these funds was primarily restricted by name to the commanding or supply officers of the five Q-ships. Provisioning the vessels thus deliberately obviated the customary naval requisition procedure. All written records of Project LQ were maintained in a secret file in the sole custody of the Chief of Naval Operations.

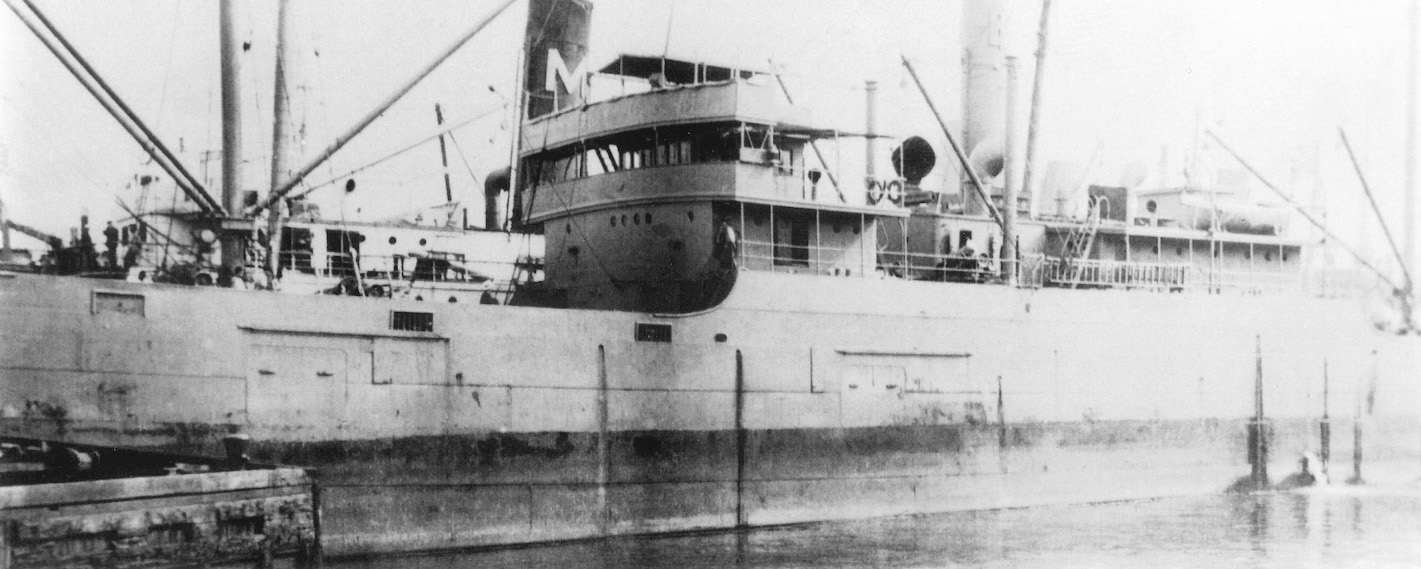

The two steamships selected by COMINCH had been constructed in 1912 and were operated by the A.H. Bull Steamship Company as the SS Carolyn and SS Evelyn. They were each 318 feet in length and of 3,200 gross tons. Taken over by the U.S. Maritime Commission, they were converted to Q-ships at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, where they were each fitted with four 4-inch/50-caliber cannon, four .50-caliber machine guns, and six single depth charge throwers. The complement of each ship was six officers and 135 enlisted men.

The Boston trawler acquired by COMINCH was a diesel-powered vessel formerly operated as MS Wave. Originally purchased for conversion to an auxiliary minesweeper, she was commissioned as USS Eagle (AM-132). Manned by five officers and 42 men, Eagle was armed with one 4-inch/50 cannon, plus two .50-caliber machine guns, four depth charge throwers, and various small arms. She was also fitted with echo ranging and listening equipment.

The tanker acquired, as suggested by CESF, was the Gulf Dawn, a typical petroleum product tanker of the 1930s. Steam-powered with a single screw, Gulf Dawn was converted to the Q-ship Big Horn at the Boston Navy Yard and armed with five 4-inch/50 cannon and two .50-caliber machine guns.

The final member of the Q-ship quintet was perhaps its most imaginative, but unrealistic. This was the three-masted schooner Irene Myrtle, a coal carrier when acquired by the U.S. Navy in 1942. She was the vessel “of insignificant appearance” suggested by CESF. Converted to a Q-ship at Thames Shipyard in New London, the schooner was renamed Irene Forsythe and fitted with new engines, concealed quick-firing armament, and a considerable variety of antisubmarine equipment.

The first of the five Q-ships to go on patrol were the former steamers Carolyn and Evelyn. After refitting, they were commissioned at Portsmouth Navy Yard as USS Atik (AK-101) and USS Asterion (AK-100), respectively. Sailing from the shipyard as naval vessels, their orders were to convert to merchant ship status on the high seas, where they would operate under the guise of SS Vill Franca (Portuguese registry, call sign CSBT) and SS Generalife (Spanish registry, call sign EAOQ). These call signs were to be used if enemy ships challenged their identity. Both secret Q-ships departed port in March 1942 under operational control of CESF, with instructions to steam independently about 200 miles off the U.S. East Coast. Their task was to lure German U-boats to the surface, then destroy them if the opportunity arose. Action was not long in coming.

On the night of March 26, 1942, Atik was cruising about 300 miles east of Norfolk, with Asterion operating about 240 miles farther south. At 2053 local time, two American radio stations received faint SOS distress signals from Atik, indicating the vessel had been torpedoed. No rescue ships were available to provide emergency assistance, hence the first searches for Atik were made by an Army Air Corps bomber the next morning, with no results.

Later that day USS Noa (DD-343) and tug USS Sagamore (AT-20) were sent to the scene. Heavy weather forced the tug to be recalled, but Noa reported sighting no survivors and only minimal wreckage in the search area. Asterion had also received Atik’s distress call and proceeded to the site of the attack, also with no positive results. It now appeared that top secret U.S. Navy Project LQ had suffered its first casualty. Atik had apparently been torpedoed and sunk, with the loss of all hands.

No further light was shed on the sinking until a broadcast from Germany was recorded on April 9, 1942. “The High Command said today that a Q-boat of 3,000 tons was sunk by a torpedo after a battle fought partly on the surface with artillery and partly beneath the water with bombs and torpedoes.” The American Q-ship program thus got off to an inauspicious start. Not only was Atik sunk on her first patrol with the loss of all hands, but Germany was now aware that the Americans had resurrected Q-ships on the high seas. After the war, German submarine logs revealed that ace U-boat skipper Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegan in U-123 had torpedoed Atik; then it surfaced and was lured into an abortive surface gun battle. U-123 escaped, then fired a second torpedo into Atik, which suffered a massive obliterating internal explosion about 80 minutes later, leaving no visible debris on the surface.

The first cruise for USS Asterion (AK-100) was probably her most active. In addition to searching for Atik’s survivors, the vessel obtained several sound contacts on presumed submarines, sighted torpedoed merchant vessels, and witnessed the rescue of survivors. One serious potential problem also came to the fore. Asterion confronted several awkward situations, including one with the U.S. Coast Guard, in which the secret activities of the Q-ship conflicted with orders given to it by other American authorities oblivious of its mission. Even more discouraging, however, was the total breakdown of Asterion’s main engines on her second cruise while she was preparing to attack a known submerged U-boat on April 11, 1942, off the Florida coast. This failure became particularly bitter after the war, when it was revealed that the U-boat was possibly U-123, responsible for sinking Atik.

During the remainder of 1942, Asterion completed four more independent cruises as a Q-ship, steaming the Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico with no successes achieved against U-boats. The ship was given an extensive overhaul commencing in early 1943, after it became evident that Asterion could probably not withstand even one torpedo hit due to lack of compartmentalization. For the next 10 months, Asterion remained mostly in the New York Navy Yard, where the installation of five transverse bulkheads and additional antisubmarine armament took far longer than projected and at much greater cost.

By October 1943, the Atlantic antisubmarine war had turned against the U-boats, and COMINCH decided Asterion would be more productive on another assignment. Accordingly, the Q-ship was converted for service as weather ship WAK-123 and transferred to the Coast Guard in January 1944.

The beam trawler MS Wave, commissioned as USS Eagle (AM-132), was even less productive than Asterion. Unlike the other four Q-ships, Eagle did not sail along convoy routes or coastal shipping areas. She spent her abortive Q-ship career in the waters near Boston, from Rhode Island Sound on the south to Casco Bay in the north. After her commissioning, Eagle remained in the Portsmouth Navy Yard to receive additional armament and sonar gear for her Q-ship role. When completed, she was redesignated as patrol craft USS Captor (PYC-40).

of the ship’s true purpose.

Captor sailed on her first cruise during May 1942, and continued to operate in her assigned area for the next year, without reporting a single U-boat contact. In May 1943, Captor was removed from secret Q-ship status and assigned as a regular armed patrol craft to the First Naval District. She was decommissioned at Boston in October 1944 and stricken from the U.S. Navy list later that month.

Largest and most formidable of the U.S. Navy World War II Q-ships was the tanker USS Big Horn (AO-45), selected in response to the recommendation by CESF. Conversion of the former Gulf Dawn was completed at the Boston Navy Yard in July 1942, by which time Big Horn was armed with five 4-inch/50 cannon, two .50-caliber machine guns, and hydrophone listening equipment. Her crew of 13 officers and 157 enlisted men, far greater than that carried by a commercial tanker, necessitated expanded living quarters amidships and on the poop. The first cruise for Big Horn began in September 1942, as a supposed straggler in a New York-Guantanamo convoy.

Thereafter, the Q-ship was attached to Naval Operating Base Trinidad and ordered to operate from that base on the bauxite trade routes, steaming independently from convoy breakup points to one of several bauxite ports. During an October 1942 convoy movement, Big Horn sighted periscopes on two occasions but could not take offensive action because of proximity to other ships. Big Horn completed three more such cruises without antisubmarine success, and returned to Todd Shipyard near New York in December 1942, where hedgehog and depth charge attack facilities were installed.

Frustrated by Big Horn’s lack of success, CESF proposed new antisubmarine tactics for the Q-ship, which were approved by COMINCH. Big Horn was now named flagship of a task group consisting of the tanker and three patrol craft escort vessels. In April 1943, after training exercises at sea with a friendly submarine, this task group, headed by Commander L.C. Farley, USN, detached from CESF, was ordered to join a convoy bound for the Azores, where it would drop astern and pretend to be a tanker straggler with protective escorts.

After operating fruitlessly in this fashion for two weeks, Big Horn engaged in her only antisubmarine action on May 3, 1943, about 500 miles south of the Azores. On that day, one of Big Horn’s accompanying PCs reported a submarine on the surface about six miles distant. Just after noon, Big Horn made a sound contact and then sighted a periscope off the starboard bow. As the Q-ship turned toward the periscope, the U-boat dove beneath the surface, and Big Horn delivered a hedgehog attack on the resulting swirl without results. Retaining contact, about one hour later the Q-ship delivered a second unsuccessful hedgehog attack, and then the target was lost. Two hours later, Big Horn regained contact with a presumed U-boat and made a third hedgehog attack. This time about five of the hedgehog projectiles were heard to explode underwater, and considerable light oil came to the surface.

The Q-ship now dropped depth charges over the presumably damaged or sunken submarine. By dawn of May 4, the oil slick had disappeared, and none of the ships in Big Horn’s task group had any underwater contacts. Big Horn now, perhaps presumptuously, reported a probable U-boat kill, which was never confirmed. On the voyage back to New York, the Q-ship fruitlessly pursued three supposed submarine sightings reported by COMINCH, causing Task Group Commander Farley to conclude that such searches were less productive than cruising as a pretended straggler with escorts behind a convoy.

After extensive repairs and alterations at the Atlantic Basin Iron Works in Brooklyn, Big Horn made another Q-ship cruise beginning in late July 1943. Now teamed with two PCs, she trailed convoys in the Azores area for over two months, with only one unsuccessful submarine attack by a PC over the entire period. The Big Horn task group arrived back in New York on October 7, 1943. One week later, COMINCH directed that no further alterations or extensive repairs be made to Big Horn without his specific authorization.

The Q-ship made a final unproductive cruise to the Azores area, accompanied by two PCs, returning home on December 31, 1943. In his patrol report, Big Horn’s skipper, by now Commander Farley, who had been detached from CESF, provided an optimistic summary. “During the period 27 November to 1 December, this Task Group was in the midst of from 10 to 15 U-boats…. Evidently the U-boats are wary of attacking an independent tanker. If the Q-ship program has contributed to this wariness, many independent merchant ships may thereby have escaped attack, and the Q-ship program has thus been of value.” COMINCH apparently disagreed with this appraisal, as Big Horn was transferred to the Coast Guard on January 17, 1944, where she joined Asperion on the North Atlantic weather patrol.

The last and least distinguished U.S. Navy Q-ship was the ill-fated three-masted schooner USS Irene Forsythe (IX-93). After being fitted with an impressive array of antisubmarine weapons at Thames Shipyard in New London, the Q-ship encountered repeated delays in reporting for duty. She was finally ready for sea in late September 1943, posing as a Portuguese fishing schooner. Ordered to report to Commander Fourth Fleet at Recife, Brazil, Irene Forsythe ran into heavy weather on the first leg of the voyage, and her hull seams opened up, forcing the crew to take her into Bermuda for repairs. Before her voyage could be resumed, COMINCH ordered the schooner back to New York, where she arrived on November 8, 1943. There, a board of investigation was convened to ascertain responsibility for material failure of the vessel.

After a thorough inspection, and in response to the subsequent report on the Irene Forsythe case by the Navy Inspector General, COMINCH made some forceful and incisive comments, surely career ending in normal times. “The conversion of Irene Forsythe is an instance of misguided conception and misdirected zeal … the failure to ascertain prior to or during conversion, that the vessel was unseaworthy is an indication of professional incompetence on the part of the officers concerned.” Not surprisingly, that verbal barrage terminated the U.S. Navy’s Q-ship program. Irene Forsythe was decommissioned on December 16, 1943, and transferred to the War Shipping Administration. One month later, after Big Horn was transferred to the Coast Guard, there were no more U.S. Navy Q-ships.

Based on the foregoing, it is easy to leap to the conclusion that the U.S. Navy’s World War II Q-ship program was an unmitigated fiasco, one worthy of COMINCH’s scathing comments on the demise of Irene Forsythe. Perhaps this judgment should more wisely be placed in context. At the time the Q-ship program was conceived in January 1942, the German Paukenschlag U-boat campaign was creating havoc along the U.S. Atlantic coast. Something immediate had to be done to stem the mounting losses of merchant vessels sailing these coastal routes. Some critics assert that President Roosevelt often acted as a dilettante in naval affairs, and his supposition that young World War II U-boat skippers would be unfamiliar with Q-boat tactics was naïve.

It should be acknowledged, however, that the limited Q-ship program he conceived could be implemented with little delay, at relatively low cost. In retrospect, it was. While it is hyperbole to evaluate the Q-ships as a triumph, consider the following: What if the ace skipper of U-123, Kapitänleutnant Reinhard Hardegen, had not escaped the unexpected gunfire from Atik and thus alerted German naval forces of the existence of operating U.S. Q-ships? What if Big Horn’s conversion had not resulted in suspicious Q-ship-style living quarters amidships and on the stern that probably spooked cautious, experienced U-boat skippers from surfacing nearby? Finally, what if Asterion’s engines had not broken down at a crucial time, preventing a possible successful retaliatory attack on a submarine, perhaps U-123?

Is it not probable that these unfortunate occurrences caused the Q-ship program to be perceived as ineffective? What if, on the other hand, any of them had gone in favor of the Q-ship involved? Might that not have tempered the adverse evaluation of secret Project LQ? Thus, before evaluating America’s Q-ship program as being inept and unproductive, it seems more prudent and intelligent to place it in the context of the dire times in which it was conceived, implemented, and then promptly terminated after its continuance was clearly no longer necessary.

Californian William H. Langenberg is a retired rear admiral of the U.S. Naval Reserve. A frequently published author on military history subjects, his writings have appeared in numerous military history-related periodicals.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments