By David Sears

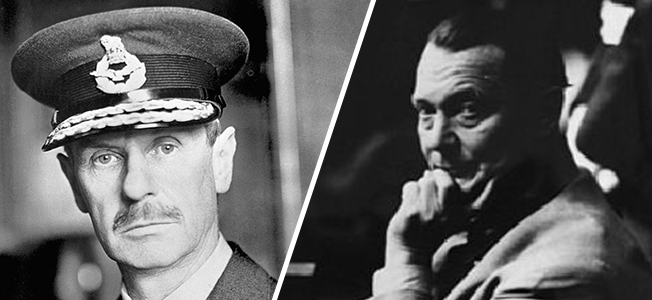

On June 23, 1944, Lieutenant (j.g.) Alex Vraciu posed for a photo with Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, commander of Task Force 58, aboard the aircraft carrier Lexington. The two stood atop the starboard wing of Alex’s Hellcat, the diminutive “Pete” Mitscher wearing his usual khakis and idiosyncratic lobsterman’s hat, Alex his flight gear. Displayed between them, just below the Hellcat’s canopy, were 19 rising sun decals emblematic of Alex’s aerial victory count. Just one kill shy of being a quadruple ace, Alex, at age 25, was indisputably the U.S. Navy’s leading fighter ace.

Four days earlier, Alex had posed for a more candid shot. On June 19, flying his Grumman F6F Hellcat as a member of Lexington’s Fighting Squadron 16 (VF-16), Alex splashed six Japanese aircraft in the space of eight minutes using just 360 .50-caliber rounds. Back aboard Lexington, he flashed a wide grin and extended six gloved fingers for an image that became part of the legend and lore of the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot during the Battle of the Philippine Sea. During the one-sided daylong melee, U.S. Navy pilots and shipboard gunners destroyed more than 300 Japanese aircraft against the loss of about 30 of their own.

Though Alex now held the Navy ace lead by a comfortable margin, other equally aggressive aviators were gaining. One still distant but fast closing competitor was 34-year-old Commander David “Dashing Dave” McCampbell, the commander of Essex-based VF-15. McCampbell had begun June 19 with two confirmed kills but had increased his total to nine by nightfall. And very soon, for a time at least, Alex would be sidelined. A few days after the Mitscher photo op, Alex and the other Fighting 16 pilots stood down. Ferried to Pearl Harbor aboard the carrier Enterprise, squadron personnel boarded the escort carrier Makin Island bound for San Diego and 30 days’ leave.

The Navy devised a number of possible gimmicks to showcase its returning top ace. Alex, newly promoted to full lieutenant, was offered the chance to fly a captured Japanese Mitsubishi Zero on a national tour. There was also talk of pairing Alex with Lieutenant Cook Cleland, a Bombing 16 (VB-16) Dauntless dive bomber aviator, for a War Bond drive, each piloting the aircraft he had flown in the Pacific. The ideas were intriguing, but Alex’s main goal was to get back into action. “I kept saying [with outsized fighter pilot swagger, Alex later admitted], ‘I don’t want to talk to a bunch of draft dodgers!’”

Meanwhile, Alex made full use of his leave time. On August 6, he was feted with a parade and stadium reception in his hometown of East Chicago, Indiana. More important, Alex found, wooed, and wed Kathryn Horn, a girl he had known since childhood. Kathryn had blossomed into an incredible beauty during Alex’s time away in college, flight training, and then the war.

Back to the Ace Race

But not even whirlwind romance curbed Alex’s impulse to return to the Pacific. After a honeymoon in New York, he was posted temporarily to Jacksonville, Florida, where an accommodating admiral interceded with Washington to get him orders back to the fleet. The need for fighter pilots was urgent. The Japanese Kamikaze threat was emerging, and with the Japanese surface fleet mortally wounded, the Navy was bolstering fighting squadrons and scaling back on bombing and torpedo squadrons. Adding to Alex’s personal sense of urgency was the fact that he was no longer the Navy’s lead ace. On October 21, Dave McCampbell surpassed Alex with his 20th aerial combat victory. Three days later, “Dashing Dave” claimed nine more in an aerial combat environment that had evolved into a shooting gallery.

Alex initially received orders to VF-19, the same squadron that had replaced VF-16 just months before. But when Alex finally reached Lexington’s forward operating base at Ulithi, he learned a November 5 Kamikaze strike had knocked the carrier out of commission and VF-19 was homeward bound. In his determination to stay and fight, Alex benefited from a second intercession, this time by Lexington commanding officer Ernest Litch, who arranged a transfer to the newly arrived VF-20 aboard Enterprise. Alex was finally poised to return to the ace race.

Taking a Hit Over the Philippines

On December 14, 1944, Alex got started with two combat sweeps, his first since early July, around Luzon’s Clark Field, part of the campaign to soften up Japanese aerial defenses before invading Mindoro, another major Philippine island. An early morning hop involved mostly ground strafing because there were few Japanese aircraft aloft. Alex burned a Nakajima Ki-44 Tojo parked at Angeles Field, a kill that did not count in his aerial total.

A second late morning hop was producing more of the same, destruction of a grounded Mitsubishi G4M Betty at Clark and two Tojos at Tala Field. Then, things suddenly went wrong. While pulling out of his last strafing run at Tala Field, Alex’s Hellcat took a hit. Oil started gushing out of a hole just above his oil tank and began spraying into the cockpit. Oil pressure dropped steadily. “I knew that I’d had it,” he recalled.

Alex climbed to 900 feet and turned west, following advice from the Enterprise intelligence officer, to get away from the lowlands in the direction of volcanic Mount Pinatubo. After trimming his aircraft and opening the canopy, Alex tossed items from his plotting board and flight suit pockets, things he did not want to have on him when he reached the ground.

Climbing out on the wing, Alex clung impulsively to the side of his Hellcat cockpit for a few seconds, what seemed to him an eternity, so that he could get farther away from the lowlands. It was about noon. He judged his altitude to be down to 400 feet. Finally, when the plane started to feel mushy—about to stall—Alex let go, raising his hands as he tumbled free, hoping to fend off a blow from the leading edge of his horizontal stabilizer. “Alex,” he remembered thinking, “what have you got yourself into now?”

“Filipino! No Shoot!”

Alex hit the ground hard. He had not even fully swung in his risers or been able to turn for a landing going with the wind. Though jarred and dazed, he already had his “mind made up that I was not going to be captured.” He drew his .45-caliber pistol and readied it as he saw men running toward him.

Knowing he was down in Japanese-held territory, Alex was conditioned to think that anyone he saw was the enemy. But these men had their hands raised, shouting, “Filipino! Filipino! No shoot!” Fortunately, Alex held his fire. “In no time at all, they got me out of my oil-soaked suit and helmet, stuck a straw hat on my head, and had me put on a shirt and a pair of pants—[so tight that] I could only get the bottom two buttons done up.”

Their leader, a young Filipino guerrilla named Luis Ramos, hurried Alex along. The Japanese were in hot pursuit. Equipped with his .45-caliber, knife, canteen, supply of atabrine tablets, and a money package, Vraciu began his tour as an American ace guerrilla in the Philippines, all recorded in a remarkable day-to-day diary that he shared with this author.

The Guerrilla Movement in the Philippines

After conquering the Philippines in the first months of the Pacific War, the Japanese made abortive efforts to persuade the people to embrace the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. Failing at this, the Japanese turned to arrests (for “baneful action”), punitive expeditions, and summary executions to stem mounting opposition. However, the roughly 7,000 islands of the Philippines spread across 1,000 miles of ocean made it impossible for the Japanese to garrison and control more than key populated towns.

At the same time, with the Philippine Constabulary demobilized, parties of marauding bandits began looting the countryside and demanding tribute from defenseless farmers. The local vigilante groups that formed to combat these raiders eventually combined forces with escaped American and Filipino soldiers to create the core of the islands’ ultimately substantial resistance movement.

It was early 1943 before clandestine operations mounted by General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) command could begin assisting and integrating major guerrilla commands. Clandestine penetration missions by American and Filipino operatives identified four classes of units: those built around a nucleus of U.S. and Philippine Army troops; those of purely local origin formed to combat uncontrolled banditry; those that were outgrowths of prewar political organizations; and a few lingering bands of roving outlaws.

For most of the war, Luzon, with its heavy concentrations of Japanese troops, infrastructure, and counterintelligence was “an island too far.” It was not until mid-1944 that SWPA agents managed to contact American guerrilla commanders in southern and central Luzon, and it was September before cargo submarines could infiltrate radio equipment and supplies.

Awaiting the American Invasion

Alex Vraciu, it turned out, had parachuted into a disorganized and contested realm outside the jurisdiction of two well-established Luzon guerrilla forces regional commands, U.S. Army Major Bernard L. Anderson’s eastern region and Major Robert Lapham’s central region.

According to Luis Ramos, Alex had landed on the Ramos family farm, part of the South Tarlac Military District and just a short distance from the enemy-held town of Capas in Tarlac Province. Hoping to link up with Captain Alfred Bruce, a U.S. Army MP and Bataan escapee turned guerrilla leader and South Tarlac commander, the rescuers led Alex on an 18-kilometer trek, only to backtrack six kilometers when they learned that Bruce, fearing an imminent Japanese raid, had retreated farther into the hills. The party was joined that day by Filipino guerrilla Major Alberto Q. Stockton, who told Alex of burying the remains of VF-20 squadron mate Lieutenant (j.g.) D.N. Baker, who had also been shot down by flak.

By noon on the 16th, the group finally reached Captain Bruce’s new camp, where Alex encountered another naval aviator, Lieutenant F. “Grassy” Grassbaugh, a TBF Avenger pilot from Hornet’s Torpedo 11 (VT-11) who had been shot down on November 6. They were in Negrito territory now, a region populated by small, dark-skinned aboriginal tribesmen that Alex learned to call Balugas.

Bruce’s camp offered welcome comforts, a chance to bathe and eat (chicken, duck, wild pork, rice, corn, and bananas), and access to books and paper scraps for keeping a diary. Alex turned over his money package to Bruce and, along with the rest of the sizable band and their Baluga allies, hunkered down to await the expected American invasion of Luzon.

Documents indicate that Bruce’s South Tarlac District reported to an Army lieutenant colonel named Wright via Wright’s executive officer, another lieutenant colonel named P.D. Calyers. Bruce’s immediate band seemed organized, but they were poorly armed and had practically no ammunition. Because of constant Japanese pressure, they could do little more than evade and lay low.

Alex’s Diary: Watching the Air War From the Ground

Confirmation came from messengers that Mindoro had been invaded, and Al Bruce predicted an imminent landing at Lingayen Gulf. Alex learned the bearded, gin-drinking Bruce had experienced his share of close calls with the Japanese. Once Bruce had watched as a fellow American, a tanker lieutenant named John Hart, shot himself in the head rather than be captured. Alex also learned there was a heavy price on his own head, one being paid by innocent Filipinos. Matter-of-fact reports told of Capas villagers being killed by the Japanese in an effort to extract information about the newly downed pilot. Under the circumstance, unless the Japanese got too close Bruce planned to sit tight to await the American landing. Except for a December 22 bombing run by two dozen Army Consolidated B-24 Liberators, the next days produced little evidence of a pending offensive.

Though he endured a Christmas Eve bout of the “drizzles,” and his atabrine supply was dwindling, Alex’s health and appetite remained strong. Alex received gifts of two fresh shirts and two pairs of pants as tight as before and with inseams five inches too short. More welcome still was a ringside view of 45 minutes of aerial dogfights between Army Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters and Japanese Jacks, during which six aircraft, one American and five Japanese, crashed.

Alex’s mood blended anticipation, envy, and frustration as he watched the fighting overhead. On December 26, his diary reports that clouds obscured dogfights (“DAMMIT!”) and records his disdain for the all too easily routed “WILD EAGLES OF JAPAN” as well as their “ANTI-AIRCRAP” ground gunners. Over the next days, Alex took four hopeful potshots with his .45 at formations of twin-engine Sally bombers flying directly overhead. He wrote that he “could well use a gunsight, mil reticule and six fifties. Always wanted to see lots of Jap planes & am now getting the opportunity. But what a way!” After those four futile shots, he decided to conserve his remaining rounds.

Alex the ace also displayed a proprietary and predictably biased interest in how his own side was performing. At midday on January 4, 1945, he watched in exasperation as “just like Army fliers,” the pilots of a dozen P-38s cruising over the valley below “missed a glorious opportunity to annihilate 9 Jap planes flying low…. Flew right over them.”

Air action, both Navy fighters and Army bombers, was intense on the 6th and, despite rainy weather, on the 7th as well. At midmorning on the 7th came the “oddest sight I’ve seen”: more than 100 Army twin-engine A-26 Invader bombers streaking low across the valley, apparently bound for Clark. Then, just after noon, two dozen Hellcats bombed and strafed outlying fields. Adding to the noise of exploding bombs and chattering machines guns was the distant but deep sound of artillery fire to the northwest, what Alex assumed was naval bombardment.

A Mission With the Guerrillas

Artillery fire resumed early the next morning. Bruce now reported that the invasion was set for the 9th. Alex and Grassbaugh were joined by another downed Navy pilot, injured Ensign Allen Stover, member of a night-flying fighter squadron (VFN-19) from the carrier Wasp.

Concentrated naval shelling kicked off at midnight and continued well into the morning of the 9th. Finally convinced that the moment was at hand, Bruce decided to dispatch a guerrilla contingent to link up directly with the Americans. His intent was twofold: to assist the invaders with maps and intelligence, but also to ensure that his men got their share of desperately needed arms and ammunition. As Alex was the only American fit to travel, he would be going along as Bruce’s representative. Alex was enthused and scarcely aware of the perils ahead.

Trekking north, the band skirted the foothills on the west side of the valley, using special caution as they approached and crossed any roads. The guerrillas traveled in stages, picking up more men as they went. They spent the first night at Major Stockton’s satellite camp, where the party swelled to 75. The next morning they passed within a few kilometers of Camp O’Donnell, the terminus of the Bataan Death March, where thousands of American and Filipino prisoners were held in squalor. After reaching that day’s destination, a Tarlac District camp run by Eliseo V. Mallari, Alex encountered a contingent of four more rescued American air crewman, including Ensign James W. Robinson, a VF-20 squadron mate who also had been shot down on December 14.

The four Americans declined to join Alex’s journey as the force, now totaling nearly 100, set off early on January 12 headed for the large provincial municipality of Mayantoc. This leg took them into the domain of American guerrilla Albert S. Hendrickson, an Army private brevetted to captain, USAFFE. Alex would soon learn how factions like Hendrickson’s jealously guarded territorial prerogatives and stewed on internecine grievances.

Crisis in Mayantoc

The crisis moment came in Mayantoc on January 13. Alex’s force had bivouacked in the town plaza while he met with Mayantoc’s mayor and chief of police, a local guerrilla major named Asuncion, and the American wife of a native villager. The party was on its way to lunch when it was suddenly confronted by an armed and glowering guerrilla. “He had a Japanese pilot’s helmet on his head, half-cocked, and his rifle partly pointed at me,” remembered Vraciu.

“You Huk!” he shouted.

Huk was short for Hukbalahap, an anti-Japanese movement comprised of Central Luzon peasant farmers (the English translation was “The Nation’s Army Against the Japanese”). Originally a prewar communist-oriented political organization, Hukbalahap had joined forces with the broad front of anti-Japanese resistance organizations. They would eventually mount a bloody post-World War II rebellion against the Philippine government, but even at this stage the Hukbalahap, which held sway over an area between Tarlac and Manila, had a reputation for fanaticism and terror exceeding the bounds of the struggle with the Japanese. To some, Huk meant a righteous popular movement. To others, though, it was a provocation.

Alex instinctively grasped his service pistol, but he could see the armed man was as much puzzled as belligerent. “No! I’m an American! What’s going on here?” Then, getting no answer but sensing the man’s indecision, Vraciu said, “Okay, take me to your leader.”

The party was following the man toward the plaza when one of the guerrillas in Alex’s group suddenly ran toward him and was just as suddenly felled by a burst of carbine fire. “[T]hey practically cut this man in half … and he bled to death there in ten, fifteen seconds.”

Still under fire and equal parts startled and infuriated, Alex (as documented in Eliseo Mallari’s and Alberto Stockton’s written reports to Alfred Bruce) ran forward shouting, “Stop firing! Stop firing!” The timely intervention likely prevented a full massacre. As it was, when the firing ceased, one of Bruce’s USAFFE troops lay dead, another was wounded, and roughly a quarter of Alex’s force had fled in panic.

Captain Hendrickson the Drunkard

The perpetrators of the incident turned out to be a contingent from Hendrickson’s North Tarlac District under a Filipino officer named Cleto. A parlay of sorts ensued, though it mostly involved shouted insults. Cleto pronounced Bruce a thief and a brute “doing nothing but sleeping in the mountains.” Hendrickson not Bruce, Cleto asserted, held jurisdiction over all of Tarlac Province.

Not surprisingly, Cleto’s better armed contingent prevailed. All of Bruce’s men except Alex and Stockton were disarmed and sent to confinement in several Mayantoc homes. They were subsequently released to return to Bruce’s camp.

Alex’s quest for freedom now detoured into the surreal. With Alex perched atop a small horse (which repeatedly turned to nip at his rider’s legs), Cleto’s men departed Mayantoc just after midnight January 15. They marched all night through countryside rife with Japanese to reach Hendrickson’s headquarters near the town of Gerona. Arriving there at midmorning, Alex got his first glimpse of the South Tarlac commander. The impression was not good: “Capt. H. a drunkard all right. Big blow to boot. Hopped up on liquor and then sends out men to attack.”

The next uneasy hours only deepened Alex’s first impression. Hendrickson and his unruly subordinates lay passed out by midafternoon. Belligerent and often incoherent, Hendrickson ruled with a heavy, impulsive hand. “He was living like a Capone off the land,” threatening to betray Filipinos who did not meet demands for food and liquor as “pro-Jap” when the Americans arrived. Meanwhile, Hendrickson seemed content to wait for MacArthur’s advancing troops, almost as if they should report to him.

January 16 brought an alert. A sizable Japanese force was reported bound for a river crossing near Hendrickson’s camp. Armed with a carbine and 75 rounds of ammunition, Alex joined a tense but anticlimactic night-long vigil. He was stunned by his unlikely transformation from aerial knight to jungle ground pounder. “I’m laying on my stomach on the side of this river and waiting for the Japanese. I said to myself: ‘What’s a good fighter pilot doing on his stomach in the middle of this Godforsaken country…?’”

Rendezvous at Panique

By the time the sleepless men straggled back into Hendrickson’s camp the following morning, word finally came by runner that American GIs would be reaching Panique, a town north of Gerona, by mid-afternoon. Hendrickson was at last disposed to move and determined to make a grand show of it.

As it set out on the afternoon of the 17th and moved north on the road to Panique, Hendrickson’s procession took on a quixotic air. A horse-mounted Hendrickson led the parade—Alex and a few others were also on saddleback —with guerrillas on foot behind. Flags—American, Philippine, and even guerrilla—fluttered, and a bugler trumpeted raucously. The clamor inevitably attracted followers, mostly women, children, and dogs from the villages en route. Just outside Panique, the procession encountered its first American GI, a bewildered checkpoint sentry from the Army’s 129th Division, an Illinois outfit.

Cleared to continue, the parade finally reached advanced elements of the 129th, and a relieved Alex Vraciu was finally in American hands. An American brigadier general appeared to personally debrief him, a process that was repeated three times during the next few days as Alex passed through the lines.

In a day or so, Alex boarded the amphibious command ship Wasatch off Lingayen. There he encountered a foreign correspondent who had been aboard the Lexington during the Marianas campaign. The reporter recognized Alex, scraggly beard notwithstanding, and in exchange for an exclusive story promised to get word of Alex’s safe return to Kathryn.

An Instant Celebrity on the Lexington

Eventually Alex reached Ulithi and reported aboard the Lexington. With his Japanese officer sword and pistol and his store of firsthand accounts of Philippine resistance life, Alex was an instant shipboard celebrity. During Lexington’s transit back to Pearl Harbor, Alex, basking in the celebrity, clung stubbornly to his trimmed beard, a sore point with the Lexington’s executive officer. He simultaneously clung to his determination to stay in the Pacific, somehow arranging a transfer to another squadron for the inevitable carrier strikes on Japan’s homeland.

It was not to be. Because Alex knew names, conditions, and circumstances from his extended time behind enemy lines, his possible loss to the Japanese could simply not be risked. Alex’s aerial combat days were done, his ace tally capped at 19. He was reassigned to the Naval Test Center, Patuxent River, Maryland, for the duration.

Alex Vraciu ended the Pacific War as the U.S. Navy’s fourth-ranking fighter ace. The Navy’s overall leading ace was David McCampbell, a Medal of Honor recipient with a final combat total of 34 aerial kills, many of them in the closing days of the war. Meanwhile, Alex, though a recipient of the Navy Cross, has been nominated for but has never received the Medal of Honor.

Alex is my first cousin and my hero. I really enjoyed reading this article.

A very interesting article! Thanks for posting. *A note: Ensign Allen J. “Smokey” Stover flew with VF-81 from the USS Wasp. He was shot down on 6Jan45 over Clark Field. He also reported back to his squadron on 8Feb45 at Ulithi. Did he travel with Vraciu?

Side note: I lived in the next province south, Pampanga, for two years and Tarlac, while calmer today, is still known for it’s wild and wooly ways. Alex was fortunate to get out as well as he did.