By Alexander Zakrzewski

In the early evening of September 12, 1683, the citizens of Vienna watched from the ramparts of their beleaguered city as 3,500 winged horsemen poured down the slopes of the Kahlenberg Heights and into the heart of the besieging Turkish army. Clad in embroidered steel armor, exotic animal skins, and with their hallmark wings arching majestically overhead, they fell on the enemy, according to one eyewitness, like “angels from heaven.” For their part in the relief of one of Europe’s most important cities that fateful day, the Polish Husaria won lasting fame as one of the most celebrated cavalry units ever raised.

But who were these mysterious horsemen about whom so little is widely known yet whose image has been so romanticized over the centuries? Their story begins in the late 14th century and follows the erratic course of Polish history.

In February 1386, the Lithuanian Grand Duke Jogaila, having agreed to be baptized in the Catholic faith, married the 12-year-old Polish Queen Jadwiga and was crowned King Władysław II of Poland. This pivotal moment in European history not only resulted in the Christianization of the sprawling Grand Duchy of Lithuania, but also extended Poland’s political and cultural influence across a vast area that today encompasses most of the Baltic States, Belarus, and Ukraine.

Whereas medieval Polish armies had fought the bulk of their battles to the west, in the following centuries they marched primarily eastward to face a diverse array of new adversaries, including Swedes, Muscovites, Cossacks, Tatars, and Ottoman Turks. As a result, Polish military styles and doctrines became an eclectic blend of Eastern and Western influences.

Like the feudal states of Western Europe, Poland’s armies in the 14th century were epitomized by the heavily armored mounted knight, but by the 15th century the advent of gunpowder and professional armies had created the need for new, more versatile forms of cavalry. In Eastern Europe this was especially true as the main area of operations was essentially one vast plain stretching from the Carpathian Mountains to the Caucasus. This was cavalry country through and through, and unlike in the West, Eastern armies remained predominantly horse based. Among the unique forms of horsemen to arise during this period was a type of Serbian mercenary cavalry that the Poles dubbed “Racowie” after the medieval Serbian region of Raška.

The Racowie were a light cavalry who fought unarmored except for a long, light lance and an asymmetrical “Balkan” shield, which they often emblazoned with a winged-claw design or, in some cases, actual feathers tacked together to form a “wing.” Because of their skill at long-distance raiding, the Racowie were known in the Balkans as “gusars” (freebooters). When Serbia was overrun in the 15th century by the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire, the gusars made their way north into Hungary, where they served as auxiliary cavalry in the armies of Matthias Corvinus, and eventually even farther north into Poland.

The Hungarians were so impressed by the wily Serbian horsemen that they soon began raising their own “huszár” regiments. Unlike their Serbian counterparts, Hungarian huszárs took the form of armored, heavy cavalrymen complete with mail shirt, helmet, shield, and lance, and trained to fight in large formations against the armored Turkish Sipahi cavalry. The Poles quickly adopted the heavier Hungarian style for their own Racowie units and opened recruitment not only to Serbs and Hungarians, but to Poles and Lithuanians as well. By the early 16th century, units of “Husaria Cavalleria” began appearing regularly in Polish army registers.

The Husaria quickly proved to be as valuable to Poland’s armies as they had been to the powerful Hungarian state to the south. Among their first notable appearances was the Battle of Orsha in 1514, where they served as part of the 30,000-strong cavalry army that Grand Hetman Konstanty Ostrogski used to smash an invading Muscovite force of 80,000. At the Battle of Obertyn in 1531, they made up almost 56 percent of the cavalry Hetman Jan Tarnowski used to sweep a much larger Moldavian force from the field. However, despite their proven worth, Husaria units during this time were motley formations of different types of horsemen largely lacking in uniformity and used in the support of heavier cavalry units. For example, in 1564 the hussar company of the powerful Lithuanian nobleman Filon Kmita Czarnobylski was made up of 140 hussars and 60 Cossacks. That all changed in 1575 with the election to the throne of one of the most influential military minds in Polish history.

By the time he assumed the throne at age 42, Prince Stefan Bathory of Transylvania was a hardened campaigner who had studied military matters in the West and spent most of his life fighting in defense of his Carpathian homeland. Among his first acts as king of the newly formed Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was a drastic reorganization of the country’s military. Under Bathory, the Husaria were transformed into an independently functioning national cavalry arm recruited from among the Polish-Lithuanian nobility. Their weapons, armor, and organization were standardized for the first time, and their tactical role was changed to that of a versatile heavy cavalry unit designed to decisively smash enemy formations. Henceforth, the Husaria assumed an unprecedented importance in Polish military doctrine as the mailed fist of the army.

The first of Bathory’s remodeled Husaria companies were heavily influenced by the Hungarian cavalry styles so prevalent in the king’s native Transylvania. The largest piece of armor was the “anima” iron breastplate, composed of a series of overlapping lames fixed together in a manner similar to the Roman “segmentata” armor. A breastplate made in this style offered greater flexibility than one solid piece and was further strengthened by a ridge running down the middle.

The Husaria also wore on their heads the lobster-tailed pot helmet or “zischagge” popular with both cavalry and infantry throughout Europe during this period. The zischagge offered effective protection not only for the head and face, but it also had a series of protective lames that extended down the back of the neck in a design resembling a lobster tail. Beneath the breastplate, the Husaria wore a mail coat, which provided additional protection for the wearer’s arms while iron gauntlets protected the hands.

The Husaria’s most unique weapon and one that would become almost synonymous with Polish cavalry in the centuries to come was the lance or “kopia.” The five-meter-long weapon was made of light, elastic types of wood and was hollowed from point to handle for added maneuverability. Despite being richly painted, the kopia was a single-use weapon as it shattered on impact. Consequently, very few specimens survive to this day.

The kopia’s effectiveness often depended on the adversary as the reduced weight of the weapon meant that it could fail to pierce heavier types of armor. However, the 17th century French soldier and engineer Guillaume de Beauplan described another aspect of the kopia that has been perhaps forgotten over the centuries and may further explain the Husaria’s deep attachment to it despite its expense and limited use:

“The point is decorated with a pennon of white and red, or green and blue or black and white —always two colors and about four to five feet in length,” wrote de Beauplan. “It is used to disorient the opponent’s horses as the moment the Hussars have lowered their lances and begin charging the enemy the pennons make considerable noise cutting through the air and cause the enemy’s horses to break their formation.”

Regardless of whether or not Beauplan’s account is accurate, there is no doubt that the long kopia with its billowing pennon added yet another frightening element to the already intimidating sight of a fully armed Husaria charge. As, it can be assumed, did the wicked sound of hundreds of lances shattering upon making contact with the enemy lines.

With his lance broken, the Polish hussar also carried with him an assortment of close combat weaponry from which to choose. On the left side of his waist belt, each man carried a Hungarian-style saber or “szabla” that was weighted at the top of the blade to increase the lethality of its slashing blows. Beneath the saddle was also a “koncercz,” a 1.6-meter straight blade with a triangular tip used for thrusting through armor. Should lance or blade fail to fell an adversary, the hussar could reach for either his skull splitting “czekan” war hammer or, most reliable of all, a pair of pistols holstered on the saddle.

All Husaria units were organized into “choragiew” (literally meaning banners but commonly translated as companies) of 100 to 150 horses and commanded by a “rotmistrz” (rotamaster or captain), who was usually a nobleman of considerable means. The captain raised his company by calling together his “towarzysze” (companions) who were themselves lesser nobles from his district and responsible for their own horses, retainers, and camp servants.

Although each company received its pay from the crown, the captain alone assumed the tremendous cost of raising, training, and provisioning his men in a system designed to spare the state an enormous immediate financial burden in time of war. The captain was further aided in his duties by a lieutenant or “porucznik,” who was usually a trusted veteran companion who stood ready to command if need be.

During the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the prevailing cavalry tactic in Western Europe was the Spanish “caracole,” which called for the cavalry to advance toward the enemy in ranks 10 horses deep, fire their pistols, then wheel around, reload, and attack again. By comparison, Bathory’s Husaria were instead deployed to deliver a single, rapid knockout blow. The main battle formation was the “huf” (from the German “haufen” or battle formation) and usually involved a few hundred men, though large “hufy” could be well more than a thousand men. Advancing in lines three to five horses deep at most with the companions in the front ranks and their retainers behind, a typical Husaria charge began with a trot toward the enemy.

Once the horsemen were about halfway, the order came down to lower lances, and the front ranks spurred their horses forward into a gallop and crashed headlong into the enemy. The supporting ranks continued advancing at a canter, ready to support the attack if need be. A well-timed Husaria charge had a devastating effect and was immediately followed by waves of light horsemen or infantry to mop up what was left of the opposing army.

Along with Bathory’s standardization in weapons, armor, and tactics, the Husaria also adopted a unique and defining accoutrement whose purpose remains debated to this day, their “wings.” Many modern sources continue to falsely claim that at high speeds the fluttering of the feathers created a sinister “hiss” that frightened enemy horses. However, this theory, along with the notion that they added to the horse’s speed or served as protection against the lassoes of the ransom-hungry Tatars of the steppe, is pure hyperbole. In truth, the wings of the Husaria are a classic case of an old military tradition dying hard.

The early Balkan forefathers of the Husaria painted wings on their shields and even tacked on feathers in various designs. As the shield was slowly phased out of the hussar’s arsenal, the wings migrated from the arm to the saddle and eventually to the rider’s back. Proof of this is the fact that the wings worn by the first Polish Husaria companies were not the grand arches so often depicted in artwork. Rather, early wings constituted a single, flat, painted strip of wood lined with a single row of feathers and affixed to the back of the saddle. It was only in the latter half of the 17th century that this relatively simple ornamentation evolved into the magnificent spectacle for which the Husaria are best known.

Bathory’s Husaria accounted for roughly 85 percent of his total cavalry arm, which was twice the size of his infantry contingent. One of their first actions was in 1577 at the Battle of Lubieszów, where they helped destroy a much larger Danzig mercenary army during the city’s rebellion against the crown. However, aside from that notable engagement, the role of Husaria during the wars of Bathory’s reign seems conspicuously unremarkable.

The king’s long Livonian campaign (1579-1582) to wrest control of what is modern-day Estonia and Latvia from Ivan the Terrible was one of his deep raids, long wilderness marches, and longer sieges, with few opportunities for the cavalry to really test their mettle. During the siege of Pskov in 1581, the Russian winter was such that cavalrymen on patrol often returned frozen to death in the saddle, still clutching their reins. Therefore, ironically, only after the death of their great patron Bathory in 1586 did the Husaria really prove their worth.

Bathory was succeeded to the throne in 1587 by Sigismund III, a member of the Swedish ruling house of Vasa. His election was contested by the Habsburg candidate, Maximilian III of Austria, and a short civil war erupted in Poland between the two factions. The matter was settled in January 1588 at the Battle of Byczyna where Grand Hetman of the Crown Jan Zamoyski badly mauled the Habsburg forces with the aid of some 1,900 Husaria. Maximilian retreated, was captured, and renounced his claims to the Polish throne.

The beginning of Sigismund’s reign, especially his simultaneous coronation as king of Sweden in 1592, seemed to herald a new era of unprecedented power and prosperity for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Peace seemed to have at last come to the Baltic. However, the predominantly Protestant Swedes quickly tired of their melancholy absentee king whose two great passions in life were his Roman Catholic faith and his fascination with alchemy. Sigismund was soon deposed by his uncle, Charles IX of Sweden, and for the next 60 years the dynastic quarrel between the two Vasa branches provided a convenient pretext for an interminable series of wars. For the Husaria, their heyday had arrived as the opening years of the 17th century brought a series of spectacular victories that made them famous throughout Europe.

The first of these great victories came in Livonia, the great area of turmoil during this time between Poland, Sweden, and Muscovy. In the summer of 1601, at the village of Kokenhausen on the banks of the Daugava River, Krzysztof “The Thunderbolt” Radziwiłł defeated a Swedish force of 4,900 with just 3,000 of his own men by overwhelming the enemy cavalry with devastating Husaria charges that drove the rest of the Swedish army from the field. These victories were followed up with a series of further Polish successes at Dorpat, Revel, Weissenstein and, most notable of all, Kircholm, where the Husaria almost singlehandedly won one of the most decisive triumphs in Polish military history.

The Battle of Kircholm took place on September 27, 1605, roughly 12 miles southeast of Riga. The Polish commander Jan Karol Chodkiewicz, Grand Hetman of Lithuania, led 3,900 men against a Swedish force of 10,700 under the command of the newly crowned King Charles IX of Sweden. Chodkiewicz placed the bulk of his hussars on his flanks with particular emphasis on his left. First, he drew the infantry in the Swedish center from their positions by feigning retreat, only to turn and attack them head-on once their lines had thinned out. With the Swedish center engaged, Chodkiewicz’s Husaria charged and quickly overwhelmed the cavalry on the enemy’s flanks, encircling the infantry in the center and putting the rest of Charles’s army to flight. In less than half an hour, the Swedes lost 9,000 men, 60 banners, and 11 guns. A wounded Charles was sent reeling back to Sweden. In Poland, news of the victory was read aloud in the royal cathedral in Warsaw.

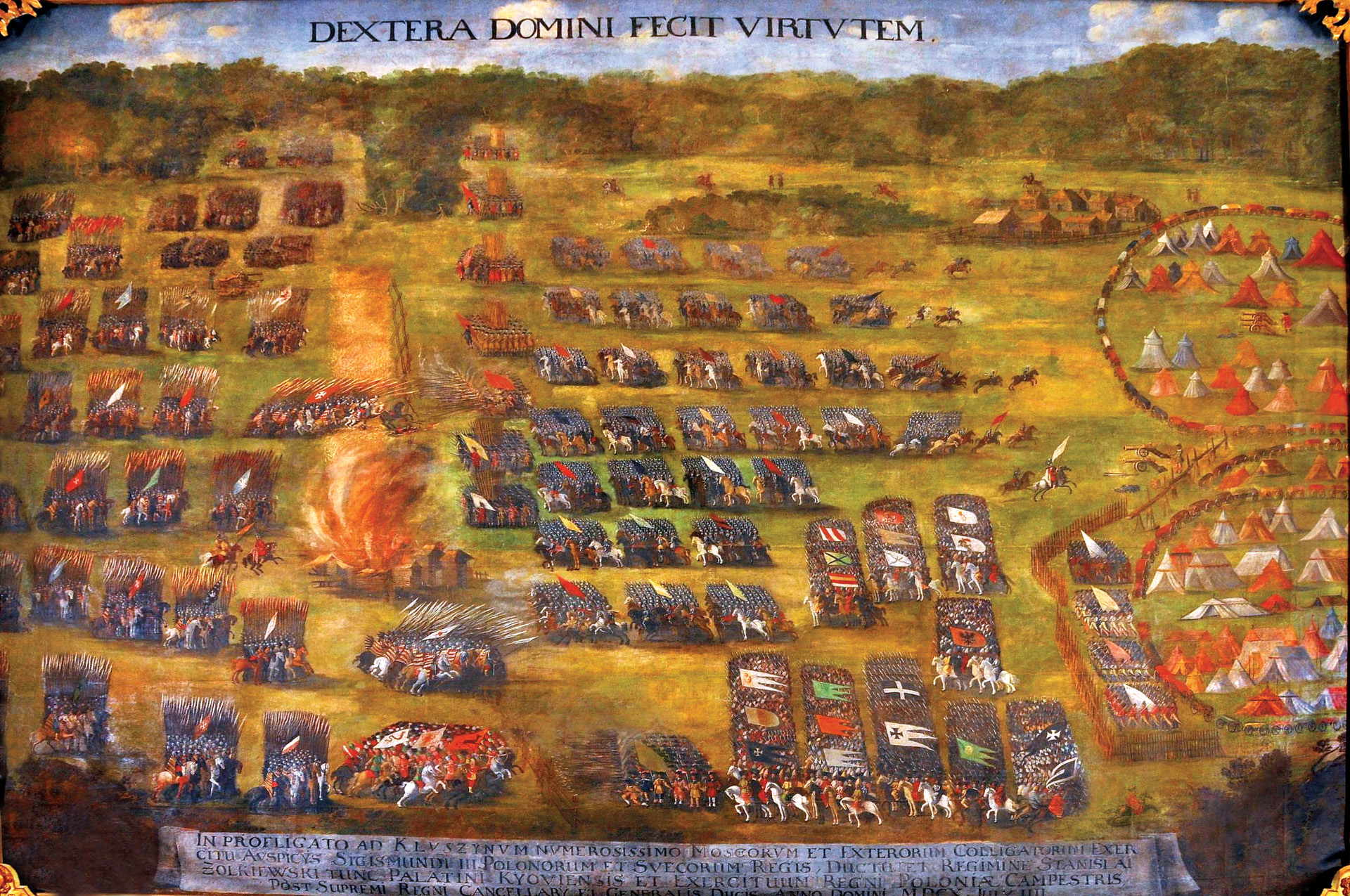

Kokenhausen and Kircholm illustrate the devastating effects a well-timed, precisely aimed Husaria charge could have against even a much larger enemy. The two engagements also illustrate the marked superiority the concerted heavy cavalry charge had during this time over Western cavalry still trained in the caracole. However, it is important to note that neither victory would have been attained were it not for the close coordination of infantry, artillery, and cavalry required to create the perfect conditions for the Husaria to strike effectively. Luckily for the Husaria, during the early 17th century the Polish army was fortunate to have been led by a series of truly brilliant battlefield tacticians. In fact, just four years after Kircholm at the Battle of Klushino in 1610, Stanisław ŻZółkiewski, despite being outnumbered five to one, skillfully used his Husaria to defeat a Muscovite army of 30,000 under the command of the tsar’s brother.

While the Husaria’s superior tactics and armament had humbled Poland’s northern enemies for the time being, a new danger was growing in the south that severely put the winged horsemen to the test. The Ottoman Turks had been steadily approaching the Polish frontier since their crushing victory over the Hungarians at Mohács in 1526. The Turks also relied on a preponderance of cavalry for increased mobility and maneuverability, and their huge numbers were unmatchable. The Turks’ elite horsemen were the sultan’s Palace Cavalry or “Sipahis.” Like the Husaria, the Sipahis were an armored shock force recruited from among the Sultan’s landowning nobility and known for their superior skill with both a saber and bow. In battle they were supported by huge numbers of irregular light horse, such as the Crimean Tatars, who fought almost exclusively for slaves and booty.

In September 1620, Zółkiewski crossed the Dniester River into Moldavia with 10,000 men, including 2,500 Husaria, to meet Iskander Pasha’s invading Ottoman force of over 20,000 men. At first ŻZółkiewski was able to keep the Turks at bay by fighting a skilled defensive battle. However, after almost three weeks of bitter fighting and numerous desertions by the Moldavian contingents, the enemy’s numbers proved too great, and the entire Polish expedition was annihilated. Zółkiewski’s severed head was sent as a gift to the sultan, and Tatar raiders crossed the Polish frontier and swarmed as far as Lwów.

The catastrophic defeat sent waves of shock through the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and a 28,000-strong army under the command of Chodkiewicz, the hero of Kircholm, was sent to parry the threat. The Poles dug in at the fortress of Chocim and once again prepared for a defensive battle. Chodkiewicz’s defenses were much more formidable than those of the unfortunate Zółkiewski and included a deep series of fieldworks in front of the ramparts. While the infantry repelled one attack after the other, Chodkiewicz personally led the 8,000 Husaria he had with him in fierce sorties and counterattacks. After a month of constant fighting and bad weather, the Turks’ resolve was broken, and both sides agreed to an uneasy peace treaty.

For the Husaria, their crucial role in such spectacular victories as Kircholm, Klushino, and Chocim solidified their importance as the Polish army’s elite arm. The latter battle in particular, which saw them man the ramparts at times alongside the infantry, earned them a reputation as universal soldiers that could fill any battlefield role when needed. Not surprisingly, the Husaria’s success and prestige, coupled with their noble pedigree and the fact that they were the only purely Polish (and Lithuanian) unit in the army, soon fostered a regimental culture and tradition markedly different from any other unit in the Commonwealth or indeed in Europe.

Positions in Husaria companies were coveted by Poland’s elite not just because of the battlefield laurels but because of the opportunities they offered for social advancement. Hussar pay was a third higher than that of all other troops, and after their service was complete they could look forward to rewards of land, titles, and important offices. However, despite the fact that prominent families often went to great expense to see that their sons made it into illustrious companies like the king’s or those of famous noblemen, enrollment criteria favored those with experience. Sebastian Cefali, the Italian secretary to the powerful magnate Jerzy Lubomirski, noted, “The Hussars deserve special attention as much for their incomparable bravery as for their personal dignity. They recruit the more significant noblemen and seasoned officers who have commanded Cossacks or other significant army units and would not mind serving in the Hussar cavalry as straight soldiers.”

Because the captains and their companions were cut from the same noble cloth, they addressed each other as “my lord-brother” and often ate and drank at the same table. Being a gentleman, the companion shunned menial duties such as tending the horses and foraging, which were left to the retainers and camp servants. Not surprisingly, the loyalty of the companions to their companies was deep, and regalia such as the company colors were blessed before battle and held as sacred. When falling into formation, all Husaria sang the “Bodgurodzica” (Mother of God), a 14th-century Polish hymn that was sung before the great victory over the Teutonic Knights at the Battle of Grunwald-Tannenberg in 1410.

By the early to mid-17th century, the Husaria’s religious fervor was also coupled with a level of ostentation rarely seen anywhere else on the Continent. Although the general look of the Husaria remained true to the standardization in arms and armor introduced by Bathory, wealthy noblemen took to studding their helmets and breastplates with gold and precious stones and engraving them with elaborate religious designs. Basic equipment like harnesses, saddles, and horse cloths were richly caparisoned, sabers were forged of Damascene steel, and even boots were made from rich yellow Moroccan leather. On top of the armor was worn the skin of an exotic animal, usually a spotted feline such as a leopard or panther. However, as these skins were expensive and difficult to find, lynx and wolf pelts were also worn and might be painted to resemble a more expensive beast.

By far the greatest expense in raising Husaria companies was the horses. Although there was no officially Polish stock, breeders crossed Western, Turkish, and Arabian horses to make a strong, fast mount that could bear the rigors of a long campaign as well as the oppressive Polish climate. Companions frequently brought more than one mount with them on campaign, and the horses they rode in battle were never used as draft animals. Because Husaria companies were paid by the crown according to the number of horses they could field, captains frequently doctored the company rolls to make a few extra złoty for themselves. Given that the captain spent a tremendous amount of personal funds to raise the company in the first place, this common practice was just as commonly ignored by the crown.

During the early 17th century, the Husaria were the determining factor in a string of brilliant victories across Eastern Europe and helped expand the borders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from the Baltic to the Black Sea. However, by mid-century it was obvious that the era of the heavy lancer was coming to a close. Following the Swedish Wars of the 1620s, carbines became standard armament for the first time following the severe casualties the Husaria suffered at the hands of Gustavus Adolphus’s efficient Western infantry.

Western armies also were learning to mix their cavalry units with infantry to make them less vulnerable to a sudden cavalry charge. Moreover, although the Husaria remained particularly effective against less advanced and more lightly armed Eastern adversaries such as Russians, Turks, and Tatars, the tremendous cost involved in raising and maintaining them was simply too much for a state chronically short of funds. Whereas under Bathory they accounted for the vast majority of the Commonwealth’s cavalry, by the 1630s they accounted for about half, and just 5 to 7 percent by the 1650s and 1660s.

The decline of the Husaria during this period can also be attributed to a catastrophic series of events that Polish historians call “The Deluge.” Between 1648 and roughly 1660, the country suffered a Cossack rebellion in the Ukraine, a Muscovite invasion of Lithuania, and a Swedish invasion that overran Poland. Warsaw was occupied, the countryside was devastated, and rebellious magnates added to the strife by siding with whatever invaders promised to secure their interests. For the first time in their history, the Husaria suffered a string of defeats, most crushing of which was at the Battle of Batoh in 1652, where the veteran core of the Husaria was captured and slaughtered by the victorious Cossacks and Tatars.

Obviously, for those parts of the country still resisting the invaders, raising new Husaria companies proved exceedingly difficult, and those that were raised were untested, smaller in number and much more reliant on their retainers and supporting units to bolster their lines. Still, there were some moments during the battles of liberation when the Husaria managed to achieve mastery of the battlefield. At the Battle of Warka in 1656, the newly raised Husaria companies under the command of Stefan Czarniecki completely annihilated a Swedish force. During the “Fortunate Year” of 1660, the Husaria once again proved their worth in a series of victories against the Muscovites in Lithuania and the Battles of Lyubar and Slobodyszcze in the Ukraine.

Although the foreign invaders had been expelled, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was utterly exhausted. In 1667, Poland and Muscovy signed the Treaty of Andruszowo, which saw the division of the Ukraine at the Dnieper River. This vast, rich, and strategically important region was forever lost, and the Commonwealth never recovered as a result. Adding to the national woes, in 1669 Michał Wisniowiecki was elected king. Despite being the scion of a powerful family and son of a national hero, the new king quickly proved a dull, dumb, and ineffectual choice for monarch at a time when strong leadership was desperately needed.

In 1672, Sultan Mehmet IV, well aware of the Commonwealth’s problems, crossed the Polish border with 80,000 men and took the seemingly impregnable fortress of Kamieniec Podolski. Despite the warnings of the few troops stationed along the southern frontier, the king and his ministers were caught completely by surprise and hastily signed the humiliating Treaty of Buczacz, in which Podolia and the Ukraine were ceded to the Turks along with a large annual tribute. Fortunately for the Commonwealth, it had at its disposal one of the most brilliant commanders Poland has ever produced, and it was under his leadership that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Husaria that served it experienced its last great hurrah.

Jan Sobieski is without doubt the most famous of Poland’s great warrior kings and arguably the only one to gain lasting recognition outside Eastern Europe. “The Lion of Lechistan” received his baptism of fire at the age of 22 at the Battle of Beresteczko and henceforth spent almost his entire military career fighting the Cossacks, Tatars, and Turks who plagued the Commonwealth’s southern borders. As a grandson of the great Zółkiewski, the Husaria were in his blood, and his older brother Marek was one of the unfortunates massacred at Batoh. During The Deluge he led a regiment of loyal Tatar allies against the Swedes, and in 1666 he was appointed a field hetman and given the unenviable task of guarding the southern frontier with a paltry force of just 5,000 men. It was Sobieski who had warned the crown to no avail of the growing Turkish threat, and he was determined to avenge the disaster that resulted.

In 1673, war broke out again between the Commonwealth and the Ottomans, and a large Turkish army of 70,000 once again threatened the Polish heartland. An army of 30,000 was hastily raised using state funds, contributions from the nobility, and Sobieski’s own personal fortune. On the morning of November 12, 1673, near the old fortress of Chocim, site of Chodkiewicz’s great victory 50 years earlier, Sobieski launched a surprise attack on the Turkish camp and utterly routed the invaders, many of whom threw themselves into the icy Dniester in an effort to escape.

News of Sobieski’s victory spread rapidly across Europe and made him an instant national hero. The Commonwealth’s elation was in no way marred by the fact that the evening before the battle King Michał Wisniowiecki died suddenly in Warsaw, supposedly after gorging on pickled cucumbers. Sobieski’s international fame made him the perfect candidate for king, and in 1674 he was duly elected to the highest office in the land. His ascension to the throne was followed by a string of further victories against the Turks and Tatars that stabilized the southern border and restored much lost territory.

One of Sobieski’s first priorities was military reform. During the Turkish War, few units had served him as ably as his Husaria, and one of his first measures was to raise more companies from scratch and by refitting existing light cavalry units. Sobieski was forthcoming in his belief that the Husaria were not just an elite fighting force but a national symbol unique to Poland. Under their new king the elite horsemen were restored to a position of prominence in the national army, and it was under Sobieski that they assumed the resplendent appearance for which they are best remembered. During the long and lean years of The Deluge, outfitting Husaria companies was extraordinarily difficult, and the companies that were raised wore hastily made and often improvised armor largely lacking in decoration. One of the traditions that was abandoned during the 1650s and 1660s and subsequently restored with renewed vigor by Sobieski was the wearing of wings.

Whereas earlier version were simple saddle-mounted frames, the new wings were large wooden arcs, covered with leather, trimmed with velvet and brass, and lined with a row of feathers that were often dyed for uniformity. These new wings were worn singly or in pairs and attached to the hussar’s back plate with special brackets that held them rigidly in place. Although there does not appear to have been any standardized size for the wings, the arcs were large accoutrements that extended well over the wearer.

A fully armed winged hussar clad in exotic animal skins was seen as the epitome of Polish martial beauty during the 17th century and, as mentioned, all accounts of the wings fulfilling any other role than that of an ornament are either fanciful or misunderstood. That being said, there is no denying that like the bearskins of the Imperial Guard, the war bonnets of the Plains Indians, or the masks of Samurai, the wings of the Husaria added yet another intimidating visual element to their ferocious charge.

In the spring of 1683, a massive Turkish army of 140,000 set out from Belgrade to capture Vienna, the center of Habsburg power and the gateway to the heart of Christian Europe. Realizing the common threat, on April 1, 1683, Sobieski concluded a treaty of mutual assistance with the Austrian Emperor Leopold II and promised to launch an expeditionary force as soon as possible. It was early September before the Polish king finally arrived outside Vienna with 27,000 men, including 3,500 Husaria. Because of his past successes fighting the Turks, Sobieski was given overall command of the total Christian force of 74,000 men and set about making plans for the city’s relief.

The Ottoman Grand Vizier Kara Mustafa Pasha had focused all his attention on Vienna itself and had failed to properly secure the Kahlenberg Heights, which overlooked the city and the Turkish lines from the west. Lumbering up the heights and dislodging the Turkish defenders was an arduous task, but once accomplished the besiegers would be effectively pinned against the walls of Vienna. The ensuing battle began just after dawn on the morning of September 12, 1683, and was not the quick rout that it is often described, but a brutal slog that lasted well into the evening. Though the victory was undoubtedly the result of the combined efforts of all the Christian contingents and their commanders, it was Sobieski and the Husaria who sealed the fate of the besieging Turks.

The Poles were positioned on the right of the great Christian host looking down from the Kahlenberg. At 5 pm, with both armies engaged, Sobieski drew his sword, let out a mighty cry of “Jezuz Maria ratuj” (“Jesus and Mary deliver us”) and led his 3,500 Husaria, supported by many more light cavalry units, charging down the heights and into the heart of the Ottoman army. All along the battlefield, Christian and Turk alike watched in wonder as the winged horsemen, magnificent in their armor and animal skins, lowered their lances and plunged into the Turkish cavalry sent to receive their attack. The thundering of hooves was quickly followed by the sickening sound of shattering lances and clanging steel, and the Turkish horse quickly gave way. Sensing victory, Sobieski pointed toward Kara Mustafa’s great white tent and ordered Prince Alexander’s company, which was named for his infant son, to charge straight at it. The site of the Poles in their camp and their commander fleeing for his life broke what little resolve was left in the defenders. Their rout soon descended into a chaotic retreat.

Following Vienna’s relief, praise for Sobieski and his invincible winged hussars poured in from all over the Christian world. However, Sobieski unwisely committed Poland to the War of the Holy League, which proved an endless conflict of ruinous cost that finally concluded with the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. By that point, Sobieski was dead, and the avaricious and self-serving Polish nobility elected as his successors a series of ineffective absentee kings who dragged the country into a string of disastrous foreign wars. As result, the Commonwealth entered a long period of decline that ended in 1795 with its partitioning by Austria, Russia, and Prussia, and its erasure from the map of Europe altogether.

As for the Husaria, their glorious charge down the Kahlenberg proved to be the last great moment in their long and storied history. By the start of the Great Northern War in 1700, the winged horsemen were an obvious anachronism. One of their final actions was at the Battle of Kliszów in 1702, during which a Polish-Saxon army was thoroughly defeated by a much smaller Swedish force. Following this action, the Husaria became exclusively a parade ground unit that appeared only at state functions and official ceremonies. The Husaria were finally abolished in 1775, and the remaining companions were drafted into the brigades of the new national cavalry.

Though they had ceased to exist as a military arm, the Husaria continued to play an important role in Polish history as a national symbol. During Poland’s long period of foreign domination, generations of artists and writers used the image of the winged hussar to remind the nation of a time when their country was free and powerful. Polish painters such as Jan Matejko, Józef Brandt, and Juliusz and Wojciech Kossak frequently based their work on great Husaria battles and even at times placed Husaria imagery anachronistically in moments where they were not present for patriotic effect.

The Husaria also appear prominently in numerous works of Polish literature, most notably Nobel Prize-winning author Henry Sienkiewicz’s famous Trilogy of historical novels. The legacy of the Husaria can also be seen in modern Polish military history. During World War II, the insignia of the 1st Polish Armored Division, which played a crucial role in liberating Western Europe, featured a Husaria helmet and wing. The Husaria may never again grace the battlefields of Europe, but their spirit will live forever in Poland’s vaunted military traditions.

Then the winged Hussars arrived…