By Christopher Miskimon

The First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal began with a delay. Shortly before 1:30 am on November 13, 1942, the American cruiser USS Helena spotted a Japanese task force: “Radar contact. Bearing, 312 True. Distance, 27,100 yards.”

Ahead of the U.S. task force sailed the Japanese Kongo-class battleship Hiei along with her sister ship Kirishima and a number of destroyers. The Japanese ships were sailing for Guadalcanal to shell Henderson Field, the American air base. The Japanese commander, Admiral Hiroaki Abe, had not expected to encounter enemy ships on the run into Guadalcanal, so the battleships’ 14-inch cannons carried high-explosive incendiary shells in the gun tubes. The Japanese had to wait as the crews reloaded the main armament with armor-piercing rounds before they could open fire.

The situation proved complicated, however. Hiei carried only a few armor-piercing shells deep in the ship’s magazines, and the large stores of explosive rounds for the shore bombardment stood in their way. It took eight minutes to get the high-explosive rounds stowed and to load the armor-piercing ammunition, but fortune favored the Japanese that night. The Americans failed to act quickly and did not fire a single shot during that time. Abe ordered Hiei’s searchlight switched on to help the task force spot the enemy ships and maintain their protective formation around the battleships.

When the powerful light shone out across the water, the real situation caused Abe shock, not satisfaction. The screening ships were too far apart, having drifted out of formation. Hiei was exposed. The USS Atlanta’s own searchlights snapped on. The American ship, an antiaircraft cruiser, was armed with 16 5-inch guns in eight turrets. Atlanta’s first salvo fell short, but after a quick range correction of 2,000 yards, rounds began slamming into Hiei. The shells had no effect on the thick armor of the Japanese ship’s hull, but the 5-inch rounds did heavy damage to the superstructure. Atlanta also fired on a Japanese destroyer that had turned on its own spotlight.

When the powerful light shone out across the water, the real situation caused Abe shock, not satisfaction. The screening ships were too far apart, having drifted out of formation. Hiei was exposed. The USS Atlanta’s own searchlights snapped on. The American ship, an antiaircraft cruiser, was armed with 16 5-inch guns in eight turrets. Atlanta’s first salvo fell short, but after a quick range correction of 2,000 yards, rounds began slamming into Hiei. The shells had no effect on the thick armor of the Japanese ship’s hull, but the 5-inch rounds did heavy damage to the superstructure. Atlanta also fired on a Japanese destroyer that had turned on its own spotlight.

Hiei returned fire, and several 14-inch rounds slammed into the American antiaircraft cruiser. In all, the ship suffered some 30 hits before a torpedo struck her, lifting Atlanta out of the water for a moment. Power failed as more rounds hit the hapless American ship.

The battle had become a melee. In the words of one observer, it was a “no-holds-barred barroom brawl, in which someone turned out the lights and everyone started swinging in every direction, only this was ten thousand times worse.”

Even in all the confusion, Hiei remained the focus of the American ships. The Japanese battleship was easily the largest target in the immediate area, and her searchlights pierced the darkness. The heavy cruiser USS Philadelphia and several American destroyers fired on Hiei. The destroyers’ guns were ineffective against the battleship’s hull, so they continued to focus on its pagoda-like superstructure; debris tumbled down from it onto the gun turrets below.

The punishment Hiei took in those few minutes was just the beginning of the hardship and agony the ship’s crew would experience; the ship sank the next day with the loss of 188 of her crew. It was the first Japanese battleship lost during the war, but it would be far from the last ship to sink to the bottom of the waters around Guadalcanal.

The story of the naval battles for Guadalcanal is expertly conveyed in Jeffrey R. Cox’s Blazing Star, Setting Sun: The Conclusion of the Guadalcanal-Solomons Naval Campaign of World War II (Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2020, 512 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover).

This is a thoroughly detailed account of the naval fighting in the Solomons. Rather than summarizing the action in a few pages or a single chapter, this work covers the fighting with almost minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow descriptions of officers making decisions and issuing orders in the heat of battle and sailors struggling to survive the consequences of those decisions. Despite this mass of detail, the narrative flows smoothly, keeping the reader focused on the action and able to follow the movements of multiple ships in the confusion of the fighting. The author’s analysis of the campaign is straightforward and logical. This is his third book on naval warfare in the Pacific during the war’s early years, and it stand alongside those previous volumes in quality and storytelling.

The Winter Army: The World War II Odyssey of the 10th Mountain Division, America’s Elite Alpine Warriors (Maurice Isserman, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishers, New York, 2020, 318 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover).

The Winter Army: The World War II Odyssey of the 10th Mountain Division, America’s Elite Alpine Warriors (Maurice Isserman, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishers, New York, 2020, 318 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover).

April 14, 1945, proved a hard day for the GIs of the 10th Mountain Division. The 85th Infantry Regiment attacked Hill 913 near Italy’s Po Valley, and the action soon turned into a meatgrinder. Second Lieutenant Robert Dole led the 2nd Platoon of I Company as it fell under concentrated German attack. Mortar bombs, artillery shells, and machine-gun fire ripped into the unit. Dole’s radioman, William Sims, lay badly wounded and exposed to enemy fire. Dole left cover to drag his man to safety but suffered a bad hit himself, just behind the right shoulder. It would be six hours before he could be evacuated to a field hospital. He spent over three years in army hospitals, but he never regained the use of his right arm. Dole received a Bronze Star for attempting to save his radioman and went on to a career in politics, eventually becoming a presidential candidate.

Dole’s story is just one of many in this new history of one of the U.S. Army’s most famous divisions. Most of the unit’s men never gained Dole’s fame, but they struggled and suffered alongside him in the Italian Theater in the final months of World War II. Mountain divisions were common in European armies, but the United States only raised one—for the first time—during this war. This book traces the unit’s formation, training, and combat service from the slopes of Colorado to the peaks of Italy.

Across the Rhine: January–May 1945 (Simon Forty, Casemate Publishers, Haverstown, Pennsylvania, 2020, 224 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover).

Across the Rhine: January–May 1945 (Simon Forty, Casemate Publishers, Haverstown, Pennsylvania, 2020, 224 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover).

The final months of the Third Reich were a period of great tumult: continuing combat for the soldiers of both sides, hardship for the civilians trapped in between, and grinding horror for the inmates of the concentration camps. In Western Europe, Allied armies massed against what remained of Nazi Germany’s once-formidable military power.

The only real obstacle to victory was the Rhine River, defended by desperate German troops. In the north, the British 21st Army Group conducted an airborne operation to enable an amphibious assault. To the south, General George S. Patton’s Third Army made its own crossing, while in the center the U.S. First Army managed to seize an intact bridge at Remagen and create a bridgehead. After getting over the Rhine, nothing lay in front of the Allies except inadequate defenses, cities already half in rubble, and towns that surrendered if their leaders were wise. Often, however, they were not. Along the way, the Allied soldiers liberated the camps and ground the remaining resistance under the heel of artillery, air power, tank treads, and rifles.

The last days of Nazi Germany involved a complicated series of attacks and movements. This new book encapsulates the actions of the various armies and units involved. Each section contains detailed maps and is fully illustrated. This book does an excellent job of covering the war’s twilight.

A House in the Mountains: The Women Who Liberated Italy from Fascism (Caroline Moorehead, Harper Collins, New York, 2020, 390 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover)

A House in the Mountains: The Women Who Liberated Italy from Fascism (Caroline Moorehead, Harper Collins, New York, 2020, 390 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, notes, index, $29.99, hardcover)

In late summer 1942, Italy changed sides in the war, and Nazi Germany occupied the northern portion of the country. A quartet of young women—Ada, Frida, Silvia, and Bianca—took to the mountains near Turin and became resistance fighters. They performed all the roles of the guerrilla: fighting; minelaying; transporting messages, weapons and supplies; and preventing the enemy from enjoying security in their rear areas. Ada’s mountain home became their refuge as they struggled to evict their former allies.

This is the author’s fourth book on resistance fighters, focusing on the personal stories of individuals and families at war. Detailed and well written, this work continues her tradition of thorough storytelling.

The Stringbags (Garth Ennis, Dead Reckoning Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2020, 192 pp., illustrated, $29.95, softcover).

The Stringbags (Garth Ennis, Dead Reckoning Press, Annapolis, Maryland, 2020, 192 pp., illustrated, $29.95, softcover).

The Fairey Swordfish torpedo bomber was obsolete before the war started. Slow and poorly armed, the Swordfish bore the nickname “Stringbag,” a term of both affection and irony. Despite all its disadvantages, Swordfish crews flew the plane on numerous daring missions. First, they struck the Italian Navy at anchor in Taranto in November 1940, sinking or damaging three battleships. Swordfish crews then helped in the hunt for the battleship Bismarck in May 1941; one of them launched a torpedo, wrecking the German ship’s steering gear. In February 1942, Stringbags flew against German ships making the “Channel Dash,” an attempted breakout from French ports. Despite its obsolescence, the Swordfish and its crews made their mark on the war effort.

This new graphic novel tells the story of the men who flew the Swordfish in vivid color and dramatic artwork. The author is well known for his historical military comics, and this new work incorporates his skill and attention to accuracy. Graphic novels are popular with younger readers, and books like these are a good way to introduce them to military history.

Death March Through Russia: The Memoir of Lothar Herrmann (Klaus Willman, Greenhill Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2020, 256 pp., $32.95, hardcover).

Death March Through Russia: The Memoir of Lothar Herrmann (Klaus Willman, Greenhill Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2020, 256 pp., $32.95, hardcover).

Born in 1920, Lothar Herrmann grew up in Nazi Germany. Conscripted in 1940, he joined a mountain division and in 1941 went across the Ukraine when Germany invaded the Soviet Union. Lothar served in an artillery unit, making him one of the lucky few who travelled in a vehicle. Then, as the Germans retreated out of Russia in 1944, the young German suffered arrest at the hands of the Rumanians, who promptly turned him over to the Soviets as a prisoner of war. This proved the beginning of a horrible ordeal as Lothar went to a forced-labor camp. Hundreds of his fellow Germans died in the camps just in the first few weeks, and many more would perish in the years to come. Lothar wasn’t released until 1949, returning to what was now West Germany.

Fully one-third of the German prisoners of war taken by the Soviets died in captivity. This memoir delves into the experiences of these prisoners, shedding light on their suffering at the hands of a horribly abusive regime. Relatively few books on the subject of German POWs in the Soviet Union are available in English. This work adds notably to that small number. It is well translated, with clear prose and interesting detail.

Desperate Sunset: Japan’s Kamikazes Against Allied Ships, 1944–45 (Mike Yeo, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2020, 352 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover).

Desperate Sunset: Japan’s Kamikazes Against Allied Ships, 1944–45 (Mike Yeo, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2020, 352 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover).

The kamikazes represented Japan’s last desperate bid to stave off defeat in a war they had already lost. The flower of Japanese aviation lay dead in a dozen places across Asia and the Pacific. All that remained were ill-trained youths manning the remaining aircraft with scant fuel and perhaps a bomb to increase the explosive power of impact. The idea that these men could save Japan was beyond hope and reason, but nevertheless they tried. Beginning in the aftermath of the naval battles at Leyte Gulf, kamikazes dove on Allied ships relentlessly through the battle of Okinawa. They couldn’t change the course of the war, but they did raise the price, sinking or damaging hundreds of ships and causing thousands of casualties among Allied sailors.

This is a well-done first book for the author, an aviation enthusiast and journalist specializing in the Asia-Pacific region. It includes the Japanese point of view, drawn from war records, diaries, and firsthand accounts. The author deftly explains the Japanese rationale for their actions, which is alien to Western thought. The book is smartly laid out and lavishly illustrated, providing excellent visual accompaniment to the clear and flowing text.

New and Noteworthy

From Texas to Tinian and Tokyo Bay: The Memoirs of Captain J. R. Ritter, Seabee Commander During the Pacific War, 1942–1945 (Edited by Jonathan Templin Ritter, University of North Texas Press, 2020, $24.95, hardcover). This memoir reveals the author’s service in the Seabees during the war. The work is clearly written and meticulous in detail.

From Texas to Tinian and Tokyo Bay: The Memoirs of Captain J. R. Ritter, Seabee Commander During the Pacific War, 1942–1945 (Edited by Jonathan Templin Ritter, University of North Texas Press, 2020, $24.95, hardcover). This memoir reveals the author’s service in the Seabees during the war. The work is clearly written and meticulous in detail.

The Rise of the G.I. Army 1940–1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl Harbor (Paul Dickson, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020, $30.00, hardcover). This book reveals how the U.S. Army organized itself for the coming war. Even before the nation’s industrial mobilization, the Army created a vast network of installations able to handle the massive influx of recruits.

Dead Reckoning: The Story of How Johnny Mitchell and His Fighter Pilots Took On Admiral Yamamoto and Avenged Pearl Harbor (Dick Lehr, Harper Collins, 2020, $28.99, hardcover). When codebreakers learned where Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto—the architect of Pearl Harbor—would be, a mission was planned to shoot down his plane. This book tells that story in full detail.

Hitler’s Tanks: German Panzers of World War II (Chris McNab, Osprey Publishing, 2020, $40.00, hardcover). This well-illustrated book covers the development and operational history of all major German tank designs. Attention is also given to the training and tactics of their crews.

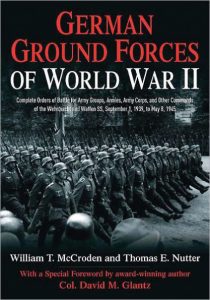

German Ground Forces of World War II: Complete Orders of Battle for Army Groups, Armies, Army Corps and Other Commands of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS, September 1, 1939 to May 8, 1945 (William T. McCrodenm, Thomas E. Nutter, Savas Beatie, 2019, $54.95, hardcover). This is a thorough reference work compiling information on all the major commands of the Third Reich’s ground forces.

German Ground Forces of World War II: Complete Orders of Battle for Army Groups, Armies, Army Corps and Other Commands of the Wehrmacht and Waffen SS, September 1, 1939 to May 8, 1945 (William T. McCrodenm, Thomas E. Nutter, Savas Beatie, 2019, $54.95, hardcover). This is a thorough reference work compiling information on all the major commands of the Third Reich’s ground forces.

Poland’s Struggle: Before, During, and After the Second World War (Andrew Rawson, Pen and Sword Books, 2019, $34.95, hardcover). This overview describes Poland’s fight to defend its borders and its efforts to deal with occupying forces.

The Atlantic War Remembered: An Oral History Collection (John T. Mason Jr., Naval Institute Press, 2020, $34.95, hardcover). This is a reprint of a classic work compiling the statements of naval officers who later attained senior rank. Most were junior leaders at the time and learned from these formative experiences.

The Battle of the Peaks and Long Stop Hill: Tunisia, April–May 1943 (Ian Mitchell, Helion Books, $59.95, hardcover). This book sheds light on a number of largely forgotten battles British troops fought in Tunisia shortly before the German capitulation. It is detailed with excellent maps.