By Susan Zimmerman

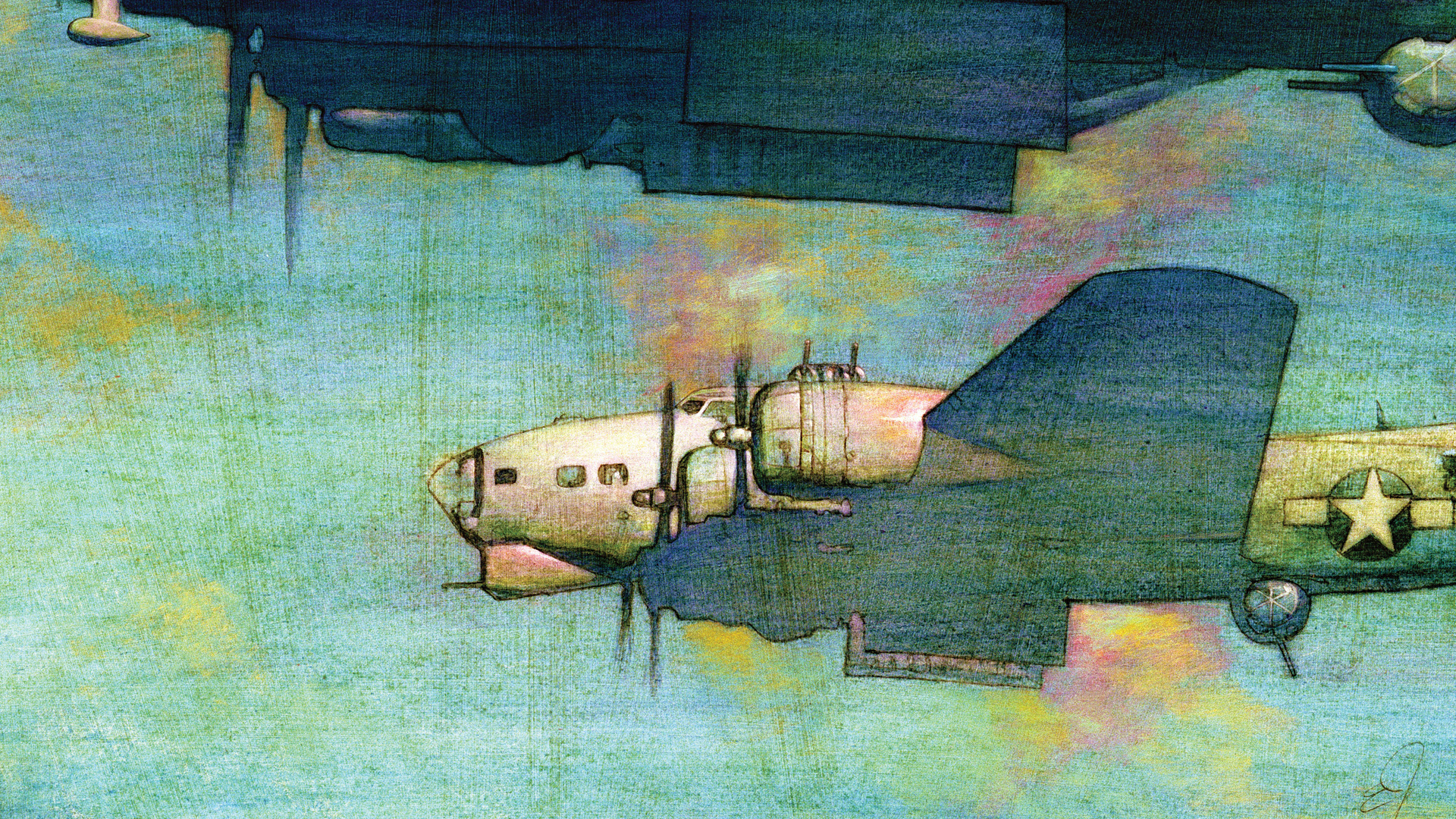

During World War II, many of England’s Royal Air Force (RAF) Class A airfields were made available to the U.S. Eighth Air Force for use as heavy-bomber bases. RAF Deopham Green airfield, in the eastern part of England, opened on January 3, 1944 and served as home for the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers of the 452nd Bombardment Group’s 728th, 729th 730th and 731st Bomb Squadrons. The 452nd was assigned to the 45th Combat Bombardment Wing, which used the group tail code “Square-L.”

Between February 2, 1944, and April 21, 1945, the 452nd Bombardment Group flew a total of 250 missions and 7,279 sorties out of Deopham Green. They dropped a total of 16,446 tons of bombs on marshaling yards, aircraft-assembly plants, aircraft component works, ball-bearing factories, synthetic rubber plants, and oil installations. They lost 128 B-17s in the process.

One bombardier remembers staying the course…

“Berlin was the most heavily defended city in all of Europe,” recalled 99-year-old Ralph Goldsticker, who served as a bombardier aboard a B-17G with the 452nd Bombardment Group’s 728th Squadron. “I flew there on my 34th mission. Normally after I dropped the bombs, the navigator and I would get back to back with our flak suits still on to protect us. That day, I stayed right in the nose watching bombs going down, because I knew I wasn’t coming back—but I did.”

It was October 6, 1944, when Goldsticker flew his 34th mission from Deopham Green, one of 418 planes dispatched that morning to Berlin to hit a munitions dump, aircraft factories, and tank factory.

According to The History of the 452nd Bombardment Group, by the group’s historian Marvin E. Barnes, “The 452nd had put up 38 aircraft, making up the lead, high, and low in the 45th Combat Wing, the primary target being the Aero engine plant in the Spandau Region of Berlin, eight miles west of the center of the city.” That mission resulted in 17 B-17s lost, one damaged beyond repair, and 234 others damaged. Three crewmen were killed in action, four wounded, and 154 missing in action.

Just Lucky

Three days later, on October 9, 1944, Goldsticker flew his 35th and final mission, targeting the marshaling yards at Mainz, Germany. Historian Barnes wrote, “The 452nd put up three groups flying lead, high and low, respectively. Thirty-four aircraft attacked [one] of the main railroads serving supplies to the front lines from central Germany…. Flak over the target was barrage and tracking, 10 aircraft received minor damage and one, major damage and one [aircraft was] missing.… [It] was seen just after the target with No. 4 prop windmilling and was last seen rapidly losing altitude near the enemy lines … all other aircraft returned safely to base.”

That same day Goldsticker wrote home: “Dear folks, Today was the big day. I flew #35…. I’ve never been so happy to finish something in my life as this. It’s a real relief to be thru with combat for a while. This idea of flying and not knowing whether you’ll be shot down today or not is not good…. I was just lucky all the way….

“When we got here, no one in our squadron had ever finished, so we didn’t have much to look forward to, but now things are different…. All of our original crew are finished flying, so we all got thru alive. Maybe tonight I’ll get a good night’s sleep for a change, knowing that I won’t be shot at tomorrow….”

In 1944 alone, there were 3,500 U.S. planes shot down by German ground-based anti-aircraft fire, known as flak, and 600 planes shot down by Luftwaffe fighters, with 41,000 airmen lost. Goldsticker flew 20 missions into Germany, 14 into France, and one over Denmark.

The tour of duty was set at 25 missions when he arrived, then increased to 30. In late July 1944, a directive stated that a crewman of a heavy bomber would not be required to participate in more than 35 sorties.

Brig. Gen. Ira Eaker, commander of the Eighth Air Force, addressing the issue of a set rotation and war weariness, wrote, “The thing that makes it most difficult to maintain morale is to have no policy, leaving clearly in the mind of the combat crewman the belief that he must go on until he cracks up … or until he is killed.… If a combat crew is worn out, they will not spring back; they are through for the war.”

Deopham Green

When Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, 20-year-old Ralph Goldsticker was working as a clerk at the Rice-Stix dry-goods store in downtown St. Louis for 50 cents an hour. He knew he was going to get drafted, so he applied to the Army Air Corp. It was July 6, 1942, when the St. Louis native enlisted at Jefferson Barracks Military Post. “I had seen movies with John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart, and the pilots were all glamorous, so I applied for the aviation corps and was accepted,” he told this author.

December 31, 1942 was the first time he was ever in a plane. After eight weeks and 46 hours flying time in a Boeing PT-17 Stearman biplane at Darr Aero Tech in Albany, Georgia, Goldsticker washed out. He wasn’t going to be a pilot, but he still wanted to fly.

So he changed course and set his sights to become a bombardier. He headed first to Laredo Army Airfield in Laredo, Texas, for six weeks of aerial gunnery training and then to Childress Army Airfield in Childress, Texas, where he trained for 12 weeks as a bombardier and six weeks in navigation.

The day before Goldsticker graduated as a bombardier and was commissioned while in Childress, Texas, he lost three friends in a training accident. Two planes collided; one went down and the other landed safely. Losing friends was a reality of war.

Goldsticker was commissioned a second lieutenant on December 4, 1943, in the U.S. Army Air Force. Next stop was MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida, where Goldsticker and his newly formed bomber crew flew together for the next four months. This was critical practice time for the young pilot, navigator, and bombardier to perfect their skills.

“Joe was 22, Marty was 20, Hank was 25 (respectively the pilot, co-pilot, and navigator); the gunners were 19 and I was 22,” recalled Goldsticker. On May 5, 1944, the 10 crewmen were assigned to a B-17 while at Hunter Army Airfield in Savannah, Georgia, and from there took off for England.

Their flight path included layovers in Labrador, Iceland, and Ireland. After arriving at their base in England, Royal Air Force (RAF) Deopham Green, located about 100 miles north of London, the crew was assigned their plane: Deuces Wild, a name inspired by the tail number 297222.

“My happy home for 10 months was a Quonset hut, but the first night there I didn’t think I was going to live. The other crew in the hut had just flown their 22nd mission, and they were firing shots at each other to see how close they could come. They were flak-happy—now it’s called PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder],” said Goldsticker. The stress on bomber crews was extreme. The average age of a crew was less than 25 years old, and the chance of survival was less than 50 percent.

He recalled how he would see fellow crewmen in the morning at breakfast, then after returning from a mission and a debriefing, he would go back to his quarters—happy to be alive— but would see four empty bunks. “I’d come back and those guys weren’t there,” said Goldsticker, sadly.

Two of the first B-17 planes to complete 25 missions were the Hell’s Angels on May 13, 1943, and the Memphis Belle on May 19, 1943. While the Memphis Belle returned to the U.S. in June 1943 for a cross-country war-bond tour, Hell’s Angels went on to rack up a total of 48 missions before returning to the U.S. on January 20, 1944, for its own flag-waving tour.

Flying a Fortress

On May 14, 1944, the Deuces Wild and her crew were assigned as a replacement after 14 out of 24 aircraft were lost on the 452nd’s mission over Brux, Czechoslovakia, two days earlier. One of the two aircraft that ditched in the English Channel, the 728th’s Why Worry?, dropped her bombs on target, with two gunners seriously wounded and three engines out en route to Brux; they all survived.

The B-17’s reputation for getting through flak and fire to complete a mission and making it home was legendary. “Without the B-17, we may have lost the war,” General Carl Spaatz, Commander of the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, was often quoted as saying.

The B-17 dropped 640,036 short tons of bombs on European targets during the war—more bombs than any other aircraft in the U.S. arsenal during World War II, even though the B-17 typically carried fewer bombs than the B-24.

The debut of the B-17 in July 1935 from a Boeing field in Seattle revealed its firepower, prompting Seattle Times reporter Richard Williams to dub the plane the “15-ton flying fortress”—a moniker that Boeing adopted and trademarked. The prototype was equipped with five .30-caliber machine guns, which increased with the development of later models.

The B-17G, the definitive version of the bomber that entered service in the summer of 1943, and in which Goldsticker flew, was equipped with 10 .50-caliber guns that included two in the chin turret, two in the top turret, two waist guns, two in the ball turret, and two in the tail.

The four-engine heavy bomber weighed approximately 65,000 pounds and was 74 feet, 4 inches in length, with a 103 foot, 9-inch wingspan and 19 feet in height. A 4,000-pound bomb load was typical for long missions, but the B-17 was capable of carrying 8,000 pounds for shorter distances at lower altitudes and almost 17,000 pounds using the external racks underneath the wings.

The B-17’s air speed was 287 mph, range 2,000 miles, and maximum ceiling 35,600 feet. A crew of 10 (including the pilot, co-pilot, bombardier, navigator, radioman, engineer, and gunners) operated the Flying Fortress. By the war’s end, approximately 12,700 B-17s had been produced by Boeing and other contractors.

A Strategic Change

It was mid-1942 when the USAAF arrived in England with the mission to destroy Nazi Germany’s industrial operations. The 97th Bomb Group led the first B-17E raid over Europe, attacking the railroad marshaling yards in Rouen, France, on August 17, 1942. (See WWII Quarterly, Summer 2015.)

The first plane off the ground was flown by Major Paul Tibbets (three years later, he would pilot the B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan). This first “test” mission of 12 bombers, accompanied by four squadrons of RAF Spitfires, was successful with no losses.

However, Eaker, a fighter pilot during World War I, who rode in one of the Spitfires, wrote, “It is too early in our experiments in actual operations to say that the [B-17] can definitely make deep penetrations without fighter escort and without excessive losses.”

Escort fighters still had limited range, which left the bombers exposed to enemy fighters before reaching their targets.

A change in tactics was needed and near at hand.

In January 1943, at the Casablanca Conference, the Allies formulated the Combined Bomber Offensive plan for around-the-clock bombing, with the USAAF conducting daytime operations and the RAF making nighttime raids on industrial centers.

The Casablanca Conference directive stated: “Your primary objective will be the progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial, and economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.”

In June 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued the “Pointblank Directive,” which was designed to destroy the Luftwaffe’s operational capability before the planned invasion of Europe but which resulted in serious losses. The double-mission attack on Schweinfurt-Regensburg on August 17, 1943, lost 60 of 376 B-17s; the second attack on Schweinfurt on October 14, 1943, (known as “Black Thursday”) lost 77 of 291 B-17s, with 600 crewmen killed or taken prisoner. The latter mission was considered one of the worst days of the war for the B-17 and Eighth Air Force. It was the final impetus for increasing the range of fighter escorts.

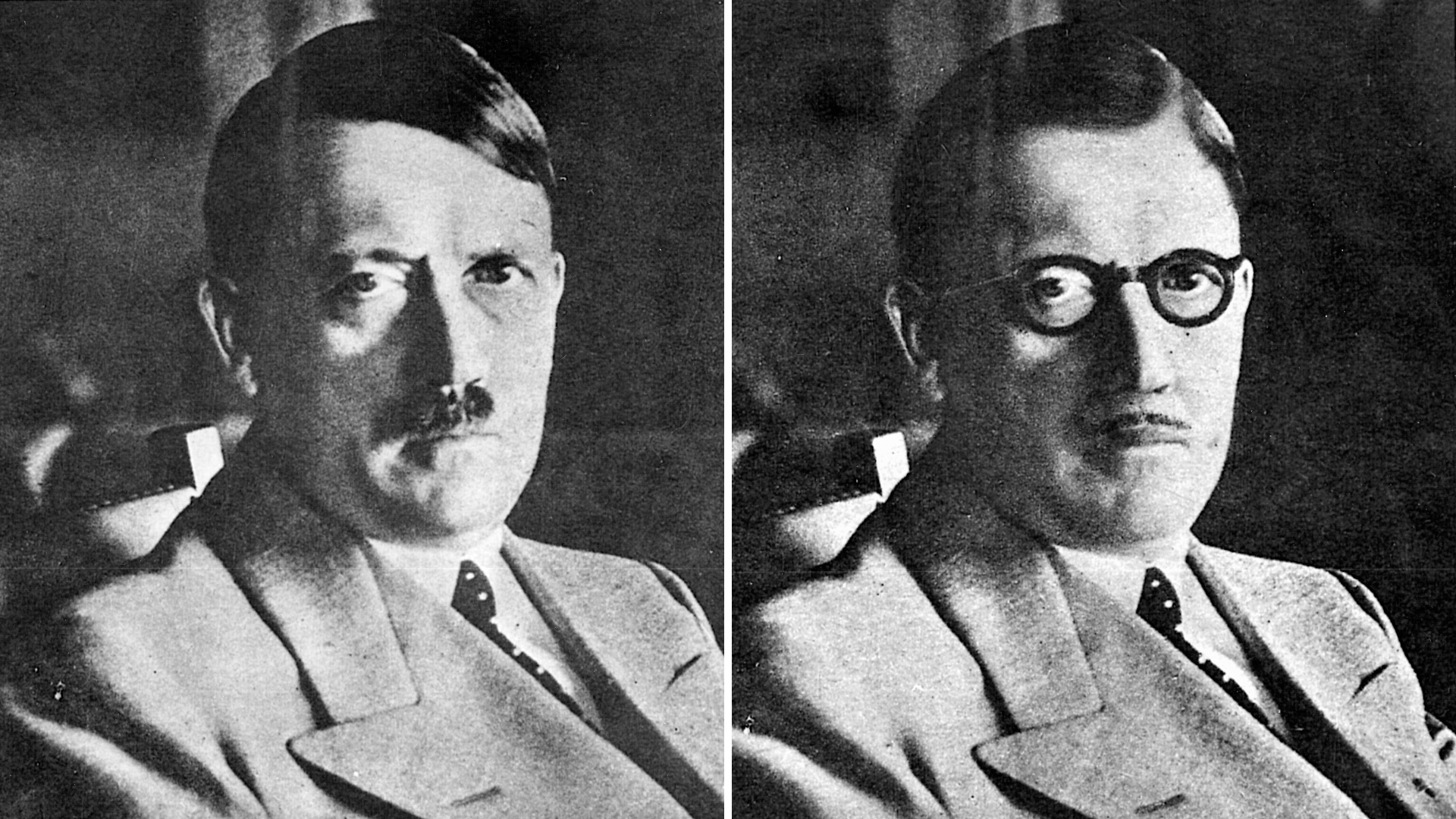

The strategy developed by the Air Corps Tactical School at Maxwell Field, Alabama, in the 1930s that called for bombers to make unescorted daylight precision bombing runs was finished; The losses from Pointblank and previous months proved it. Strategic raids over Germany were put on hold through mid-January 1944, until the North American P-51A Mustang could be fitted with external fuel tanks.

The revamped P-51D now had the range to fly to Berlin and back. The P-38 Lightning and P-47 Thunderbolt escorts were also equipped with external fuel tanks, thus extending their range.

During this bombing hold in early 1944, the original Eighth Air Force was redesignated the United States Strategic Air Forces (USSTAF), and the VIII Bomber Command was redesignated the Eighth Air Force. General Carl Spaatz now commanded the USSTAF, while Maj. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle, famous for leading the April 18, 1942, carrier-launched raid on Tokyo, commanded the new Eighth Air Force.

As the Eighth’s new commander, Doolittle implemented new fighter tactics that cleared the path toward U.S. air supremacy from early 1944 onward. Fighters were now instructed to engage with enemy aircraft after they had escorted their bombers to the targets. Fighter pilots were directed to fly far ahead of the bombers’ combat box formations, “clearing the skies” of Luftwaffe fighter opposition.

Doolittle ushered in the resumption of the strategic bombing campaign with Operation Argument. On February 20, 1944, more than 1,000 bombers and 600 fighters from the Eighth, RAF, and Fifteenth Air Force initiated the week-long operation, which became known as “Big Week.”

The next day, some 900 bombers and 700 fighters of the Eighth Air Force hit a series of aircraft factories.

By the end of the operation on February 25, approximately 3,800 sorties by B-17s and B-24s had dropped almost 10,000 tons of bombs. “Big Week” was considered the turning point for the Luftwaffe’s downfall, setting the stage for the June 6, 1944, Normandy invasion.

Hermann Göring, commander of the German Luftwaffe during the war, was quoted as later saying, “When I saw Mustangs over Berlin, I knew the jig was up.”

Bombs Away

The end of the “jig” was further settled when the Norden bombsight came onto the scene. The USAAF began using the device for daylight precision bombing in 1942, and then, in 1943, an improved version was issued to the Eighth.

The 50-pound, gyroscopically stabilized, telescopic Norden bombsight contained an electromechanical computer that was able to determine, with information entered by the bombardier, the exact point at which the aircraft’s bombs should be released for them to hit the target. During a bomb run, the bombardier would take over the flight controls through the autopilot and, with the Norden, would guide the aircraft to the precise release point.

Bombardier Goldsticker liked the Norden. “We were dropping bombs from 25-27,000 feet—five miles up in the air. You are way away from your target when you release your bomb. I had to put in the airspeed, altitude, and wind drift—and the Norden would do the rest. We would put the crosshairs on the target, and, when the crosshairs clicked, the bombs would drop. You could set it to bomb every three seconds, or every second. The lead bombardier, equipped with the Norden, would drop the bombs and the whole group—18 planes—would drop at the same time.

“The Norden was our secret weapon, although it wasn’t as good as was talked about. But it did the job and we hit the target. Let’s put it this way: when you’re five miles up, there’s a lot of variation. But most of our targets were big aircraft plants, railroads yards, and refineries, so we would get mighty close and do damage anyway. We would drop on the lead bombardier, but we had to be on our bombsight in case he was hit and we had to take over. We had holes in our plane all the time,” said Goldsticker.

Before they reached 10,000 feet, Goldsticker said that he would arm the bombs by removing the cotter pins on the bombs in his bomb bay—sometimes six 1,000-pound bombs, or 10 500-pound bombs, or 28 100-pound bombs. He made fast work of it before needing oxygen in the unpressurized plane and before the bomb-bay doors opened.

When they reached 25,000 to 27,000 feet, the outside temperatures dropped to 30 to 40 degrees below zero, and Goldsticker would don silk gloves to operate the bombsight so his hands wouldn’t freeze to the metal.

Staying warm was critical in the unheated plane. Goldsticker wore two pairs of socks, long underwear, regular pants and shirt, heated pants, fleece jacket, silk gloves, fur-lined gloves, fleece-lined boots, and fur helmet. He also wore a “Mae West” life vest (named for the “buxom blonde bombshell” actress of the 1930s and ‘40s), a parachute harness, a 30-pound flak suit, and a metal helmet. He was also equipped with an oxygen mask and hose, a headset, throat microphone, and heated suit—all of which had cables attached to various systems in the plane.

Goldsticker was also the only crew member authorized to carry a gun. The Norden was considered so secret that if the plane crash landed, the bombardier was instructed to fire his .45-caliber pistol into the bombsight to prevent it from getting into enemy hands. (By 1943, however, it was believed the Germans already had access to the Norden’s secrets from bombers shot down over enemy territory. It was also later discovered that Herman W. Lang, a Nazi spy and a naturalized U.S. citizen who worked at the Norden factory, had smuggled the bombsight’s plans to Germany in 1938.)

Mission Over Normandy

Deuces Wild’s first mission over St. Valery, France, was on May 27, 1944, followed

by five more missions within the next nine days—Leipzig, Reims, Schwerte, Bologne, and Villeneuve-St. George. Their June 3 target, Bologne, was the perfect “milk run”—no flak and no enemy aircraft.

Historian Milton Barnes noted that on June 4, “34 1,000-pound bombs and 65 500-pound bombs were dropped, missing the main point of impact but hitting railroad yards and fuel dumps. All aircraft returned.” Then it was D-Day—June 6, 1944.

Barnes also wrote, “It was 2100 hours, June 5, 1944, when the order came … that all flying personnel would report to their respective briefing rooms at 2200 hours. There was tension in the air, something big was cooking and many believed it was the day they [had] been waiting for, the big raid, paving the way for the invasion of Hitler’s Fortress Europe…. The 452nd’s target was to be the huge coastal defense guns near Caen, France, the easternmost sector of the invasion beach of the Normandy invasion.”

It was 2 am when Deuces Wild took off, one of 41 aircraft in the 452nd, armed with a total load of 216 500-pound and 608 100-pound bombs. There were thousands of planes in the sky, so they had to fly up to Scotland to get into formation and then head back down to the English Channel. Almost five hours after taking off, the aerial armada approached France. Their first target that morning was a heavy gun emplacement near Sword Beach, one of the five coastal landing areas.

Goldsticker saved the cotter pin from the first bomb he dropped that day and tagged it with the time: 06:58. They returned around 9:30 am, were fed, then took off again at around 3 pm. Their second target in the afternoon was Argentan, a railroad junction about 30 miles south of the beaches.

On the first mission Goldsticker couldn’t see the invasion fleet because it was cloudy, but on the second mission he had a bird’s eye from his Plexiglass nose of the entire fleet covering endless square miles of the Channel. The D-Day Allied invasion involved some 6,000 ships and landing craft, 50,000 vehicles, 11,000 planes, and over 150,000 troops that stormed 50 miles of Normandy’s fiercely defended beaches in northern France.

Over 2,300 sorties were flown by the Eighth’s heavy bombers during the invasion, “but we had it easy compared to the ground troops,” reflected Goldsticker, who flew 14-1/2 hours on D-Day.

Mission Over Munich

The most treacherous mission for Deuces Wild was the crew’s 25th, to Munich on July 31. Barnes wrote, “The 452nd put up 19 aircraft plus one Pathfinder Force…. The target, a machine and workshop area in Munich, was bombed…. Flak over the target was intense, very accurate, barrage and tracking. One group sustained 100% flak damage over the target, losing [an] aircraft and crew due to a direct hit about two minutes before bombs away…. Many B-17s struggled to reach home base.” Deuces Wild was one of them.

“We were 27,000 feet over Munich,” recalled Goldsticker, “when a burst of flak went off under us right after I released the bombs. It knocked out two engines, one on each side. A piece of flak came through the bottom of the plane, then pierced the quarter-inch armored seat of the co-pilot. It tore a hole in his left thigh about the size of a baseball and then it went out through the roof.”

It was 40 degrees below zero, so the blood froze as it came out, which prevented the co-pilot from bleeding to death. Goldsticker went up and sprinkled sulfa on the wound and gave the co-pilot two morphine shots, but the gaping wound was too high on his thigh to put on a tourniquet.

Once they were out of the flak zone and under attack by fighters, Goldsticker manned the two .50-caliber guns in the nose. But Deuces Wild couldn’t keep in formation on two engines and issued a “Mayday” for help from the P-51s to drive off enemy fighters.

Deuces Wild tried to land in Switzerland because it was close by, but it was fogged in, so they headed toward England. The crew threw everything out of the plane they could to lighten the load, thinking they might have to ditch in the Channel. Luckily, they didn’t.

For the last three-and-a-half hours, Goldsticker kept pressure on the co-pilot’s wound to keep him from bleeding out. Afterwards, Goldsticker received a letter from Marty, the co-pilot, saying he was going to be in the hospital for two years, in a cast from his chest to his toes. He ended up staying in the hospital for four years and had 22 operations, but he survived.

“That was our worst mission. We had about 70 holes in our airplane. My parachute was cut to shreds by flak. It was by my feet at the time. The parachute would snap onto a harness we wore in case we had to bail out. Fortunately, I didn’t need it,” said Goldsticker.

Operation Frantic: Poltava, Russia

The five-inch piece of shrapnel that Goldsticker has held onto for 76 years is a reminder of Deuces Wild’s fateful mission to Russia. Two weeks after D-Day, on June 21, the crew was awakened at 2 am and told they were flying a mission. They went through the usual briefing procedures until the curtain was pulled back.

The target was an oil refinery in Ruhland, near Berlin, but then the tape showing the route kept going east. Their destination was Poltava in the Ukraine, located in southern Russia, between Kiev and Kharkov, over 1,400 miles from their English base. They were told they’d be gone for about a week.

Deuces Wild was flying the second mission of Operation Frantic, which permitted Americans to use three Soviet airfields in Ukraine and making it possible to fly shuttle bombing missions en route to bases in Italy and England. General Spaatz, Commander of USSTAF in Europe, was in charge of the operation. The second shuttle, Frantic II, consisted of 114 B-17s and 70 P-51s flying to Russia, then on to North Africa, and back across France to England.

They took off at 5 am, bombed Ruhland, and continued heading east. At 3,000 feet they let their guard down, thinking they were out of the flak area, but, while flying over an airfield near Warsaw, Poland, nine ME 109 started attacking the group behind them. Two B-17s were shot down before their P-51 escorts drove them off. After an 11-1/2 hour flight, they landed in Poltava, Russia, and lined up with 48 B-17s, wingtip to wingtip.

Barnes wrote, “The Germans, seeing so many American planes so deep inside Germany and headed towards Russia, knew there was something very different afoot, so they sent out a recon aircraft to follow the B-17s and P-51 escort planes. The Americans didn’t know this and felt secure on their base and lined up in neat rows at Poltava. Later that night came the rude awakening; some 60 enemy aircraft attacked Poltava.”

“We were on the edge of the airfield in tents,” recalled Goldsticker, “when around midnight the Germans dropped a flare over our field and for the next hour they proceeded to bomb the airfield. When the bombs started dropping, we ran from the tent to the nearest slit-trench with the others. Shrapnel was hitting all around us. With the first lull in the bombing, I ran about a quarter-mile away and ended up in another trench with a Russian family.”

The bombing went on for over an hour. The Germans dropped regular, incendiary, and “butterfly” bombs. Two Americans were killed and 30 Russians died trying to put out fires. When Goldsticker returned to his tent, he found a five-inch piece of shrapnel that had burned through the top of his tent sitting on his cot. He kept it as a souvenir.

Of the total 73-B-17s from the 452nd, 96th, and 388th Bomb Groups, 47 were totally destroyed, 19 were damaged, and only seven were undamaged. One P-51 and two C-47s were also completely destroyed. Of the 47 B-17s destroyed, 24 were from the 452nd Bomb Group.

In a report of the incident, Maj. Gen. John Deane, Chief of the U.S. Military Mission in the U.S. Embassy in Moscow, wrote, “The Russian anti-aircraft and fighter defense failed miserably. Their anti-aircraft batteries fired 28,000 rounds of medium and heavy shells, assisted by searchlights, without bringing down a single German airplane. There were supposed to be 40 Yaks [Russian fighters] on hand as night fighters, but only four or five of them got off the ground. Both their anti-aircraft and night fighters lacked the radar devices which made ours so effective.”

During the aerial assault, the Russians would not give clearance for American fighters to attack. U.S. air operations there were governed by a 24-hour-long permission process. Though Americans initially received excellent cooperation from the Soviet Air Forces and from the local population in establishing the base, the loss of aircraft from Frantic II was a precursor of the poor cooperation that was to come from the Soviets. The following six missions were of limited success, and Operation Frantic ended in September 1944.

Goldsticker and his crew were stranded in Russia for seven days until the Douglas C-47 transport planes arrived. They then flew the southern route back home, which included overnight stops in Tehran, Cairo, Tripoli, Casablanca, and, finally, England.

We Have to Fight for It

Now, 76 years later, Goldsticker still remembers that after his final mission, “They were training returning airmen for B-29s for flight over Japan, and I had been shot at enough.” Luckily, a position for a group awards officer at Deopham Green opened up; Goldsticker took it, and he remained there from October 1944 through March 1945. After that, he headed to bombardier instructor school back in the U.S.

“When the war ended in Europe, I was in Midland, Texas, at instructor school. We didn’t celebrate too much because we were still fighting. When the war ended [with Japan], I was teaching French cadets in Big Springs, Texas. That night everyone got drunk. The war was over and I survived,” said Goldsticker.

After three years, four months, and 13 days, Goldsticker was discharged on October 20, 1945. He had flown 22 missions in Deuces Wild, 13 missions in other B-17s, and three missions as navigator in just over four months; over one 17-day, period he’d flown 11 missions.

Coming Home

Goldsticker served in the Reserves until 1958 and was promoted to captain during the Korean War but was never called to active duty. For his service, he received five Air Force medals, a medal from the Russian Government, the French Legion of Honor, the French Jubilee Victory Medal, and the Distinguished Flying Cross—the latter his most treasured award since it is the one that both Jimmy Doolittle and Charles Lindbergh also received.

“My only plan [after returning home] was to buy a car. I wasn’t worried about anything. I was 22 at the time,” said the veteran. But when he returned from the war, he was offered a job back at the dry goods store as a traveling sales representative that paid $175 a month, five percent commission, and a car.

He couldn’t pass it up, and for the next 48 years he made his living as a clothing-manufacturer’s representative covering areas in the Midwest. He retired in 1994, but he’s still driving. “I’m good to 102,” laughed Goldsticker, who’d just passed his driver’s test. (He turned 99 on October 26, 2020.)

Goldsticker returned to his hometown of St. Louis, where he married in 1948, raised three boys, and now has five grandchildren and two great grandchildren. Helen, his wife of 63 years, passed away in 2012.

Taped to a page of a scrapbook are two letters he wrote in 1944 that were returned to him; one was marked “Deceased” and one “Missing.” They were sent to his roommates from flight training at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama, and Darr Aero Tech in Albany, Georgia. Four out of his six roommates from flight training were killed during the war. Both envelopes have remained unopened since the day he sealed them, seemingly a quiet tribute to those airmen Goldsticker knew and lost.

As we page through a stack of photos of flak-damaged planes, he comments, “There is flak and more flak; you can really see it burst. There is that one plane that was cut in half, but it landed. We couldn’t do evasive action with 18 planes. We went straight and level right to the target. People would always say to me, ‘You had the best seat [in the nose turret].’”

“I was one of 16 million who served in the U.S. Armed Forces during WWII. Four hundred thousand didn’t come home,” said Goldsticker.

The only crew member he kept in touch with was Marty the co-pilot, who was 85 when he passed away. These days, he gets together with a small group of war veterans, but they, too, are getting fewer.

The cotter pin Goldsticker pulled from first bomb on D-Day and the piece of shrapnel that he’s held onto all these years are reminders that this bombardier stayed the course.

Susan Zimmerman is a frequent contributor to WWII Quarterly. She lives in St. Louis, MO.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments