By Frank Chadwick

In November 1944, an American infantry division underwent its baptism of fire in the worst conditions imaginable and acquitted itself with honor beyond anyone’s expectation. The final outcome of the campaign, however, was determined by the heroic action of only 100 men who found themselves in a hopeless situation and simply would not give up.

The men of the 84th Division—the Railsplitters—were, to use the GIs’ own language, “green as grass,” fresh off the boat from the States, and they were not going to a quiet sector to get combat experience on the cheap. Their first combat mission was to assault and reduce the Geilenkirchen Salient, a chunk of the German Siegfried Line that featured dragon’s teeth, minefields, and layer after layer of concrete pillboxes surrounded by trenches, foxholes, and barbed wire, which Lt. Gen. Brian Horrocks, commander of British XXX Corps, described as the most formidable fortifications on the entire German front.

Operation Clipper

If the GIs had been expecting their first sight of Germany to be picturesque, they were disappointed. The area around Geilenkirchen, the flood plain of the Wurm and Roer Rivers, was depressingly drab, worn, and ugly. Nondescript shabby little villages and gray industrial towns dotted a landscape unbroken by any terrain features likely to catch the eye. There were a few scattered woods and orchards, but the ground was mostly cabbage and sugar beet fields now turned to sticky brown mud by the autumn rains.

The flood plain boasted no major hills or ridges, but a series of rises on the south bank of the Wurm gradually joined to form a low plateau farther to the northeast. The low hills and rises were not obstacles to movement but did provide excellent observation posts for German artillery. Everything had an abandoned, desolate feel, made more pronounced by the absence of civilians. Most had been evacuated by the Germans before the fighting began.

There was another thing—the 84th Division would not be going into action under U.S. command. Its first offensive would be fought under British XXX Corps. Geilenkirchen was at the far northern end of the U.S. 9th Army’s area of responsibility and the far southern end of the British 2nd Army’s. The Wurm River formed the rough boundary line between U.S. General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group and British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st. Despite that, cooperation between General William Simpson of the 9th Army and Horrocks of XXX Corps was good. Geilenkirchen needed taking, but XXX Corps did not have the strength on the ground to take it. So Simpson loaned Horrocks a U.S. division to get the job done. The operation would be called Clipper.

The Geilenkirchen Salient was a tough proposition—impressive fortifications, and deep—seven miles deep, all the way back to the Roer River with interlocking fields of fire and few covered routes of approach. Asking a green American division to tackle this as its first assignment was asking a lot. The fact that Simpson and Horrocks were willing to do so spoke volumes about their confidence in the ability of the U.S. training system to turn out combat-ready divisions capable of hitting the ground running. When it came to the Railsplitters of the 84th Division, they were right.

The plan for Operation Clipper was simple. Most good ones are. On November 18, the British 43rd Wessex Division would drive in the northern side of the salient, and the U.S. 334th Infantry Regiment, 84th Division would drive in the south, leaving Geilenkirchen exposed and cut off. The 333rd Infantry would then hit Geilenkirchen itself the next day.

Attack on the Geilenkirchen Salient

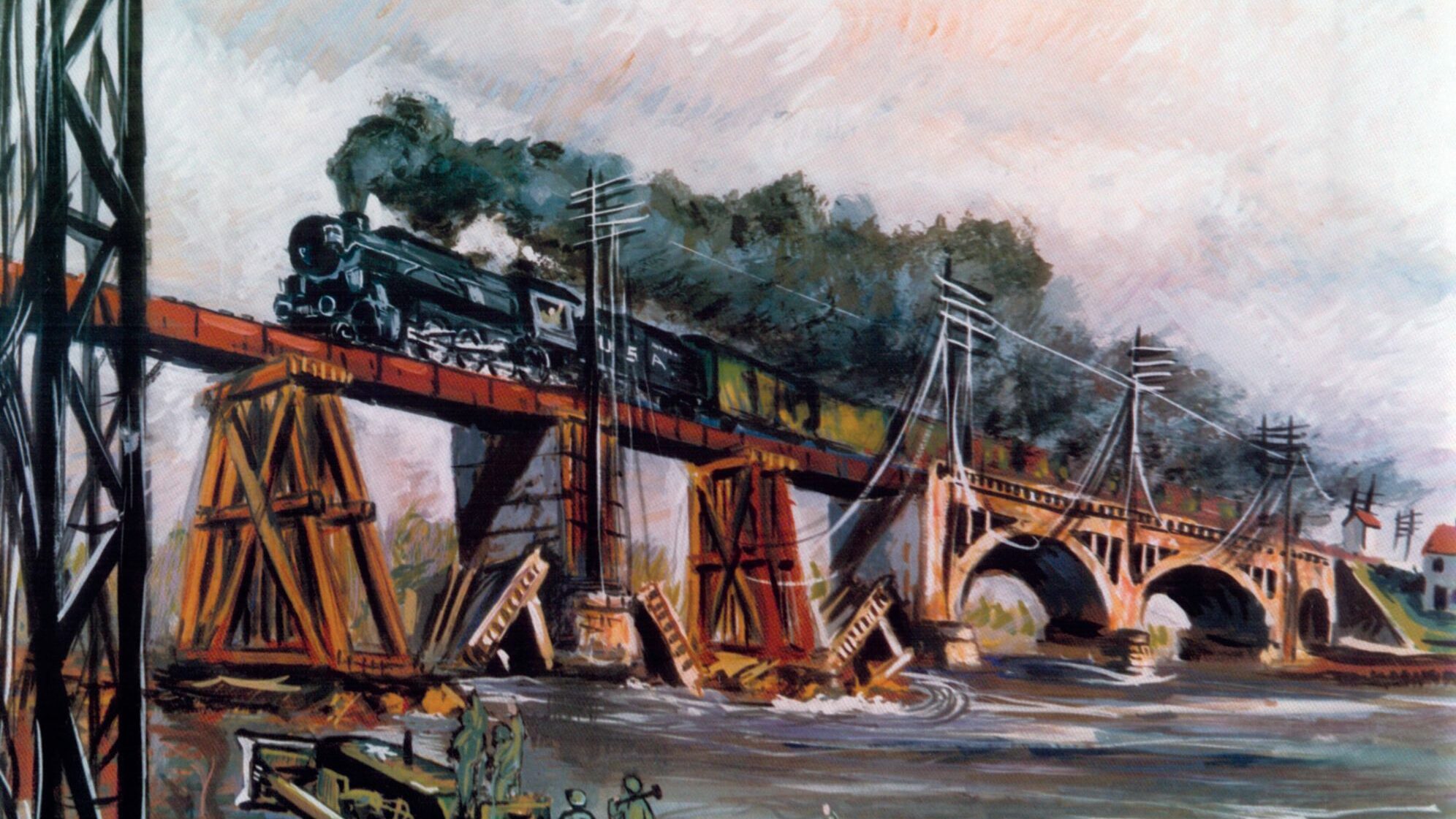

The 334th attacked on the morning of the 18th with two battalions up, the key attack being by the 1st Battalion on the right through a heavily mined orchard and entrenched rail embankment, then two clusters of concrete pillboxes, and finally across 2,000 yards of open fields to seize the fortified village of Prummern. The attack bogged down almost at once under artillery and small arms fire at the rail embankment, but the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Lloyd H. Gomes, moved up and led the forward rifle companies and platoons himself.

This got the attack moving again, and it rolled forward, overwhelming all German resistance. The battalion paused to reorganize before attacking Prummern and then swept in and cleared the village house by house. The regiment’s 2nd Battalion made similar progress on its left, but against lighter resistance.

Casualties in the two attacking battalions were moderate, 10 killed and 180 wounded, but by the end of the day the 334th had destroyed a battalion of the defending 183rd Volksgrenadier Division, inflicting 450 casualties, of which 330 were prisoners. Among the dazed German POWs was a veteran officer, stunned by what had happened. “We knew we were facing new troops and expected it to be easy,” he said, “but these men fight better than any troops I saw in Africa, Russia and France.”

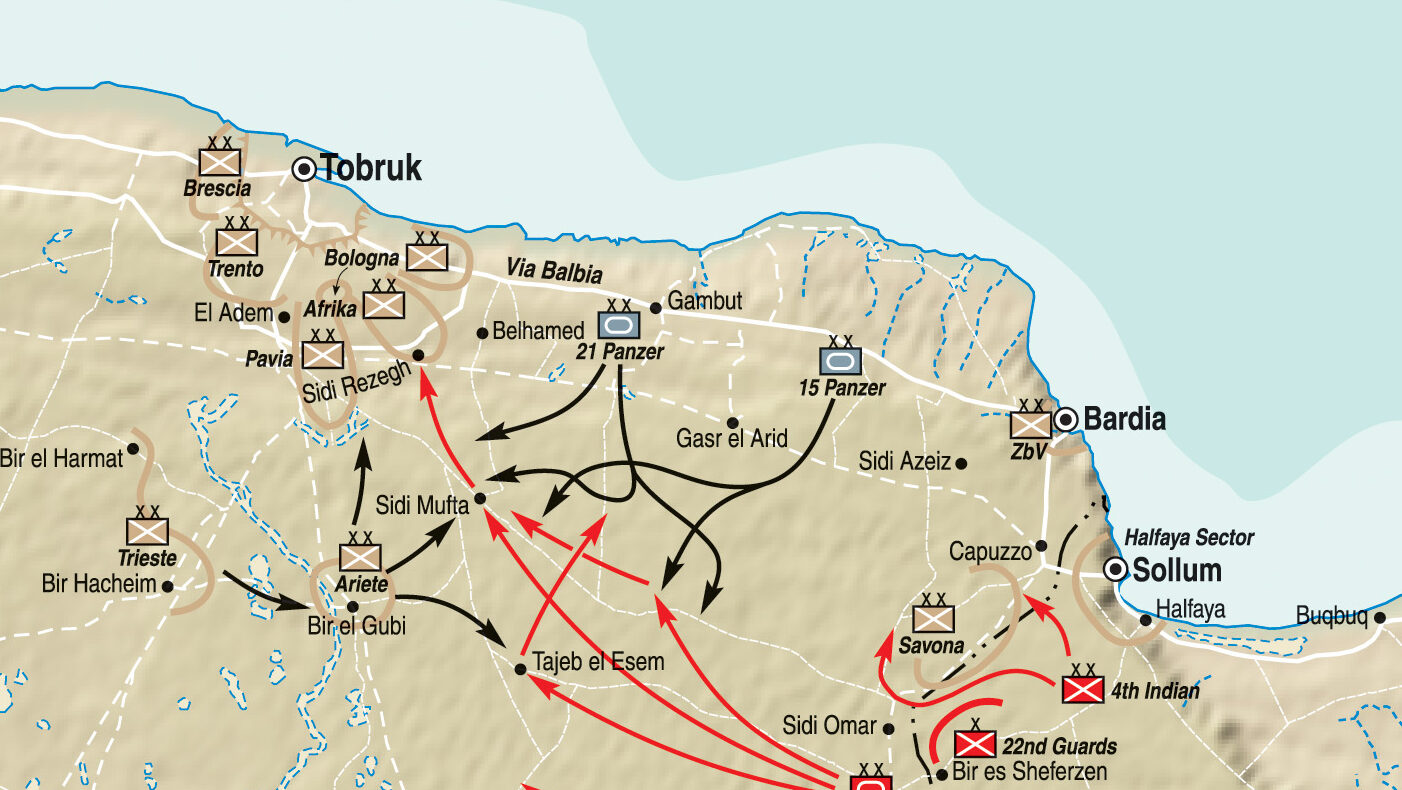

The next day, the 333rd attacked and cleared Geilenkirchen with light casualties, and another battalion of the 183rd Volksgrenadiers was kaput. In the early morning hours of the same day, however, a new enemy appeared near Prummern—the veteran 9th Panzer Division. On the 19th it launched a counterattack, with the 1st Battalion, 10th Panzergrenadier Regiment and six tanks of the 2nd Battalion, 33rd Panzer Regiment, and retook much of the town.

The 1st Battalion, 333rd Infantry still held the surrounding orchards, and regimental committed its reserve battalion along with the M4 Sherman tanks of the attached British Sherwood Rangers Yeomanry. There followed several days of tough back-and-forth fighting for Prummern and the wooded hill behind it—dubbed Mahogany Hill—but Prummern was secure by the 20th and Mahogany Hill by the 22nd.

Stalled by Rain and by Panzer

The division pressed forward to the northeast, closing on the villages of Muellendorf and Beeck, but the advance slowed to a crawl, in part because the Germans threw in more troops to halt the division. Both the 15th Panzergrenadier Division and elite 10th SS Panzer Division “Frundsberg,” fresh from its fight at Arnhem during Operation Market-Garden, were committed to stop the Railsplitters and absorbed the remnants of the 183rd Volksgrenadier Division.

The SS division, which began entering the lines on November 23, relieved the battered 9th Panzer Division, which was pulled back to refit for the upcoming Ardennes Offensive. Neither German division was up to full strength, but they were on the defensive, held excellent positions, and had strong cadres of seasoned veterans.

And then there was the mud.

It rained almost every day that long November—a cold, steady rain, sometimes mixed with sleet. The floodplains of the Wurm and Roer were usually wet this time of year, but in November 1944 the region received over twice as much rain as the average, and it became a vast sea of mud. Roads were axle-deep canals of mud. Foxholes dug in the low-lying beet fields became waterlogged, and soldiers slept on the ground beside them instead of in the water. Some foxholes filled up to the very top, and to keep under cover when shells hit nearby, riflemen had to hold their breath and duck their heads under water.

Weapons became coated with mud and jammed. Trench foot reached epidemic proportions. Tracked vehicles could not leave the roads, wheeled vehicles often could not move even on the roads. Hot chow was a distant memory. Men fought and died for high ground just to get out of the mud. By November 28, the advance ground to a halt. It was time to try something different.

Item and King Forward, Love in Reserve

All of the advances of the 84th Division to date had been made by only two of its three infantry regiments. The third regiment, the 335th, had been detached to support another U.S. division farther south. Now it rejoined the Railsplitters and was available to get things moving again.

The main front had stalled in the face of strong German positions in Muellendorf and Beeck, and on Schlachen Hill. In addition, there was a fortified backstop position on Toad Hill and in the village of Lindern—held by the 1st Battalion, 21st SS Panzergrenadier Regiment,10th SS Panzer Division, giving the entire position depth. The attacks by the 84th Division’s main body, however, had drawn the bulk of the German troops into this position, and its left, or southeastern, flank was open, covered only by miles of muddy fields and a long antitank ditch. Behind the antitank ditch was the town of Lindern, and it sat astride the main German supply route. If the Railsplitters could get a firm hold on Lindern, the rest of the position would fall easily. Getting a hold on Lindern would be the job of the 335th Infantry.

The original plan was for the regiment to throw all three battalions at Lindern, one behind the other, but that was reduced to a two-battalion attack when the regiment’s 2nd Battalion was switched west for an attack on Toad Hill. Then 1st Battalion was held back as a reserve, and the Lindern attack came down to a single infantry battalion.

Major Robert W. Wallace’s 3rd Battalion, 335th Infantry would attack with two companies, Item and King, forward and one, Love, in reserve. They would make a long approach march at night and jump off before dawn. The approach march was from the southwest and would require a gentle left turn to make a head-on approach to the target. Navigating at night and in extended assault formation would be tricky, so a landmark was picked out. As the troops reached the north-south highway from Gereonsweiler to Lindern, they would wheel left and advance along its axis, with the highway becoming the boundary between the two assault companies. If they became disoriented, they could orient at first light on a tall church steeple in Lindern, or the brickyard on the southwest side of town.

After the wheel, the assault companies would cross the antitank ditch and press forward, ignoring any pockets of resistance, until they had crossed the railroad behind Lindern. They would dig in on the far side and await the inevitable German counterattacks. The reserve company would follow them and clear Lindern of any pockets of resistance and then reinforce them. The regiment’s 1st Battalion in reserve would be available for additional strength as needed.

The attack was also to be supported by the 40th Tank Battalion, which was now attached to the division, but the tanks would not go in with the first wave. Surprise was believed to be more important, and so the tanks would wait for word from the infantry as to when they should advance. In order to communicate with the tanks, each of the leading rifle companies was given one heavy SCR 509 radio in addition to two SCR 300 backpack radios for communication with battalion and regiment. The SCR 509, with its longer range, was only barely man-portable, and in fact was carried in two loads: one man carried the radio itself, and the other the heavy battery pack that powered it, with a power cable connecting them.

“A Phi Beta Kappa of Soldiering”

Company K, which played such a remarkable role in the coming battle, was an unlikely candidate for the history books. It had not yet been in serious combat, but had already lost half of its officers—including its commander—in a jeep accident nine days earlier. First Lieutenant Leonard Carpenter, its unpopular executive officer, seen by the men as stuffy and distant, had assumed command, and three of the four platoon leaders were replacement officers who had arrived in the last few days. They hardly knew their men’s names, let alone strengths and weaknesses. Morale was shaky, and the men had little confidence in their company commander or new platoon leaders.

Most rifle companies have one or two key noncommissioned officers to whom others look for leadership. In King Company, that man was Technical Sergeant George O. Prewitt, the platoon sergeant for 1st Platoon. One of his comrades remembered him as “a football hillbilly out of North Carolina with little learning, [but] he was a Phi Beta Kappa of soldiering.” Almost alone among the soldiers of King Company, Prewitt accepted and worked with Lieutenant Carpenter, the new company commander, without reservation. Perhaps he saw something in Carpenter the other men had not yet noticed, but soon would.

The Attack 0630, 29 November

At 6:30 am, still pitch black on November 29, both assault companies crossed the line of departure in the same formation, two rifle platoons up, one in reserve, and the weapons platoon split up to give support to the rifle companies. Each platoon advanced with two squads up and one back, and Staff Sergeant Jeff Parker, who led King Company’s third squad of 1st Platoon, recalled, “We went out in a column of twos. The columns were about 25 yards apart with three yards between men because it was still dark and we wanted to stay pretty close.”

King Company attacked with Lieutenant Pozyck’s 3rd Platoon on the left, Lieutenant Romersberger’s 1st Platoon on the right, and Lieutenant Smith’s 2nd Platoon in support. Lieutenant Lockard’s 4th (weapons) Platoon gave up one 60mm mortar squad to each of the three rifle platoons, and its two .30-caliber light machine gun squads to 3rd Platoon on the battalion’s open left flank. Lockard, with his weapons platoon headquarters party and the company’s spare SCR 300 radio, brought up the rear behind 2nd Platoon. Each man carried only the essentials: rifle, gas mask, three chocolate D-ration bars, one canteen of water, and two bandoliers of ammunition. The men left their overshoes behind. Speed meant more than keeping dry.

Lieutenant Carpenter and his small command group advanced with the two lead platoons. A rear company command group, led by the executive officer, Lieutenant Johns, and the company first sergeant, Julius Phagan, moved with the supporting platoon. Carpenter was up front to ensure that the lead platoons got their navigation right and pushed on, regardless of what they ran into. Johns and Phagan would do the same for the support elements.

Shortly after they crossed the line of departure, several German flares erupted in the night sky, illuminating King Company. Every man froze in place, as trained to do. As the flares drifted down on their parachutes and burned out, every man waited for the tearing sound of German MG-42 machine guns, but there was no German fire. They had not been spotted. As soon as the light flickered out, the advance resumed.

“They Can’t Hit You if They Can’t See You”

The plan started going wrong as soon as the attacking companies came to the “highway” to Lindern at 6:45. It was actually no more than a narrow dirt road. Fortunately, the men of King Company’s 1st Platoon recognized it immediately as their landmark and alerted Carpenter, who ran over to 3rd Platoon to tell them to wheel. King Company’s two assault platoons came on line with the road to their right and headed toward Lindern.

They crossed the antitank ditch with difficulty. It was partly flooded, and the soft banks collapsed in sheets of mud as the men tried to climb out, but 1st Platoon and most of 3rd stayed together as units. Then they encountered flanking fire from German machine guns, and a few mortar rounds landed among the soldiers of 3rd Platoon but, remarkably, caused no casualties. The troops went to ground, but Lieutenants Carpenter and Romersberger and several NCOs encouraged the men to crawl out from under the tracers of the blind grazing fire and keep advancing.

First Platoon’s Sergeant George Prewitt recalled, “There were four machine guns firing at us. I began to yank the men up, and I kicked one in the ass. Sergeant Matuska did the same.”

“They can’t hit you if they can’t see you,” Lieutenant Carpenter shouted over and over, and the men followed him forward.

About this time, a German round clipped off the antenna of the SCR 300 radio carried by Private Paul North, Carpenter’s radio man. A runner was sent back to 4th (weapons) Platoon to get the spare antenna from the company’s other SCR 300, but the advance continued.

Three Platoons and No Radio

The two assault platoons sprinted forward and in moments were in Lindern, the outlines of the buildings growing visible as the sun rose. At first Carpenter was unsure they were in the right place, there was no church steeple visible anywhere, but then he caught sight of the brickyard and knew they were on the objective. Contrary to the pre-attack briefing, Lindern was one of the only towns in the area that did not have a standing church steeple, a mistake that would cost the battalion dearly in the next hour.

The assault platoons ran through Lindern, firing from the hip and throwing grenades at any sign of resistance, but never slowing up. They came out on the far side and sprinted across the open ground to the 20-foot-deep rail cut. Carpenter later reported, “We hit the railroad north side of Lindern. We went down a bank about 20 feet high and ran up the other side. We saw some long buildings that looked like barracks and turned out to be a German rest camp. Some men threw grenades into the buildings. Nothing happened. Fifty yards in front of the barracks we found a fence. There we started digging in—two-man foxholes. We stopped there because we knew we were going to dig in 50-100 yards the other side of Lindern. A long, sloping hill was in front of us. We dug in on the reverse slope of a very slight rise in the ground, the crest of which was 250 yards in front of us.”

The 84th Division’s history describes the rail line as sitting on top of a 20-foot-tall embankment, and the U.S. Army’s official history, The Siegfried Line Campaign, also refers to the rail embankment. The eyewitness accounts from King Company, however, make it clear the railroad ran through a deep cut, not along the top of an embankment. Carpenter specifically mentions sliding down into the cut, then scrambling up the other side, while another soldier talks of tanks coming into the area across a highway overpass—not through an underpass tunnel. Equally telling, however, King Company continued to take scattered small arms fire from Lindern throughout the day, which would have been unlikely if there was a 20-foot-tall earthen berm between them and the enemy.

King Company began digging in at 7:45. Lieutenant Carpenter remembered someone had asked the time. Now there was nothing to do but report their success and wait for the rest of the company to show up. Unfortunately, it was going to be difficult to contact battalion headquarters that day.

German small arms fire had taken off the antenna of the company’s forward SCR 300 radio, and the antenna of the big SCR 509 had been damaged as well. The heavy two-part radio had been abandoned at the base of the rail embankment so the two-man team could keep up with the advance. A runner had been sent back for a spare SCR 300 antenna, but he never returned and, as the sun rose, there was no sign of the rest of the company.

Carpenter conferred with Item Company to his right, and discovered a full company was not present there either—only 35 men of its 3rd Platoon, and a five-man mortar squad, all under Lieutenant Creswell Garlington. They did not have a working radio.

Carpenter had only 60 of his own men under his direct command, the four men of his forward company command group, 32 men of 1st Platoon under Lieutenant Romersberger and Technical Sergeant Prewitt, the 1st Platoon’s attached 60mm mortar squad with six men, but only 18 men from Lieutenant Pozyck’s 3rd Platoon.

Separated and Under Friendly Fire

Romersberger and Pozyck were both new replacements. Romersberger, even though he had been with the company only four days, had already displayed excellent leadership under fire during the advance and would continue to play a key role in the company’s survival. Less is recorded of Pozyck’s contribution, except for a report by one of his NCOs that a piece of shrapnel “went right through Lt. Pozyck’s helmet,” perhaps leaving him temporarily stunned or disoriented. It is more likely Pozyck’s contributions were tangible and considerable, but simply never written down. Pozyck received one of the first Bronze Stars for the action afterward and was soon promoted to first lieutenant.

The only senior NCO who had made it forward was George Prewitt. Carpenter co-located his foxhole with Pruitt, who effectively became the company first sergeant for the balance of the action.

Pozyck’s 3rd Platoon had a harder time moving forward than 1st Platoon, as it had been closer to the enfilading fire of the German machine guns on the left and had lost time engaging them. The artillery prep on the brickyard, through which they had to advance, had been late and so had delayed them another five minutes. The follow-on rifle squad remained pinned down near the antitank ditch for too long. When the sun rose they were still in the open in front of Lindern and the now alert SS defenders and were forced to surrender.

The left wing of 3rd Platoon’s forward echelon, over 20 men, including the light machine gun section attached from weapons platoon, 3rd Platoon’s attached 60mm mortar squad, one complete rifle squad and four men from another, became separated from the rest of the company around 7:30 and crossed the railroad farther to the left. Although the company’s main body could see them, they were too far away for Carpenter to control, and it is unclear who actually stepped up and assumed command of this group.

They started to dig in on a low hill, but then were hit by U.S. artillery fire, including white phosphorus rounds, and pulled back into an apple orchard. At about 9 or 10 am, they were hit again by friendly artillery fire. Two men were killed and at least one wounded, and they withdrew across the rail line, carrying their wounded but leaving behind one light machine gun and the mortar. Shortly after noon the 18 or 20 survivors, of whom six were wounded, encountered a dug-in German infantry force that took them prisoner. Carpenter later sent runners over to the abandoned position in the apple orchard and recovered the light machine gun.

But what had happened to the rest of King and Item Companies?

The rear element of King Company, 2nd Platoon, the rear headquarters party, and the weapons platoon headquarters failed to keep closed up behind the lead platoons and lost contact in the dark. When they crossed the Lindern road, the officers did not recognize it as such, perhaps being confused by the reference to a “highway.” The 2nd Platoon’s senior NCO realized the mistake but was unable to convince his platoon leader of the error. The group was being led by Lieutenant Johns, the company executive officer. The company first sergeant was also with this group and had been ordered by Carpenter to maintain contact between the assault platoons and the follow-on echelon,; he failed to do so. The group continued north, well off its intended path, until it encountered entrenched German infantry, was pinned down by fire in the open, and forced to surrender at daybreak.

Nearly the same thing happened to the bulk of Item Company. It had farther to go than King Company (being on the outer arc of the wheeling maneuver), and had navigation problems of its own. Not only was there confusion at the road crossing, but the church steeple in a village to the north, combined with the absence of a steeple in Lindern, further slowed and misdirected the advance. Most of Item was caught in the open fields around Lindern at daybreak and either driven back or forced to surrender.

By 8 am, the two assault companies of 3rd Battalion, 335th Infantry had effectively ceased to exist. There were only 100 men on the far side of the rail embankment, and they had no means of communicating their position to the rear. From the point of view of battalion headquarters, they had marched into the darkness and vanished in a storm of small arms and mortar fire.

“Hold Our Ground at All Cost”

As Love Company, the battalion follow-on echelon, tried to move forward to clear Lindern it was pinned down by heavy fire short of the line of the antitank ditch and forced to dig in. Elements of the 21st SS Panzergrenadiers in the entrenchments in front of Lindern were alert, full of fight, and not going anywhere. German artillery fire on the area forward of Lindern was accurate and intense. As far as 335th Regiment could tell, the attack had been a total disaster and both rifle companies had been wiped out.

For the men under Carpenter’s command, the first real action after crossing the rail line came on King Company’s left. About 20 minutes after they began digging in, three German medium tanks appeared on the road from Lindern, crossing the railroad at the single overpass in the area, and driving north almost through 3rd Platoon’s position. Private First Class Morton Reuben remembered, “I grabbed a bazooka round and put it in Wolfenberger’s bazooka. He fired and hit the middle of the tank but it bounced off…. The second round hit a tree and tore it up. The tanks passed out of sight.”

Bazooka and small arms fire, while causing no visible damage, had nevertheless encouraged the tanks to leave the area, which is not surprising since they had no close infantry support and could not know how weak the U.S. position was.

Between 9 and 10 am, the company began taking friendly artillery fire on the far left. This would eventually drive the isolated left wing of 3rd Platoon back. At about the same time, however, three different German tanks appeared from the north. Carpenter remembers them as Tigers, and the U.S. official history concurs. The majority of “Tiger tank” reports turned out to be Panthers or Panzer IVs, but elements of the 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung (Heavy Tank Battalion) were in the area and were certainly committed against Lindern in the following days, so it is not improbable that three Tigers were present that morning. King Company had already identified the first group of three tanks as “mediums,” so they knew the difference, and they would get a very close look at these new ones.

Two of the German Tigers halted about 300 yards away while the third continued to advance directly into the American position. There were several German-held pillboxes about 500 yards away in the same direction, and Carpenter could also see four more German tanks moving about 800 yards away. That made 10 German tanks sighted in quick succession, but the most immediate problem was the lead tank moving into 3rd Platoon’s positions on the left.

Even though 1st Platoon still had a few bazooka rounds left, the U.S. infantry was nearly defenseless against heavy armor, and Carpenter had to make a quick decision: should they remain in place and risk getting overrun, or should they try to infiltrate back to their own lines through Lindern? He took a moment to confer with his senior NCO, Technical Sergeant Prewitt, “and we decided to hold our ground at all costs.”

Holding, but Cut Off

And they did hold—in part because of the cool-headed marksmanship of 3rd Platoon’s Private Robert Nordli. He told the story a few days later without dramatics, as if it was just another day at the office. “The tank came up to our front right in our lines. The tank commander stood up from the turret to observe. We moved back about 100 yards to get a better defilade position as the tanks came up. Unfortunately we had run out of bazooka ammunition. I hit the tank commander with an M1. He slumped over. The tank continued past us into Lindern for about another 100 yards, then backed up and returned to the vicinity of the pillbox.”

The death of the commander of the leading German tank—probably the platoon leader—deprived the German armor of leadership at a critical time and caused the tanks to pull off to a safer distance. Nevertheless, it now appeared the Germans were alert to the presence of the Americans in their rear. More German infantry began assembling around the pillboxes, and tanks moved back and forth along the road to the front.

One hundred infantry with a handful of 60mm mortar rounds and two or three bazooka rockets could not possibly hold out against the force assembling unless they got help, and getting help meant getting word back to battalion or regiment. Carpenter sent a party of four volunteers back to retrieve the abandoned SCR 509 radio set, but, although they recovered it and got it working, its antenna was sufficiently damaged that it could only receive faintly and not transmit.

The only other option was to send runners to try to get through. The odds of success did not seem high. In Carpenter’s deceptively casual words, “We knew there were Germans in and around Lindern in back of us because we were always getting fire from our rear.” Four soldiers volunteered anyway. They did not make it. One was killed and the other three captured.

“Like Hannibal Crossing the Alps”

By 1 pm, the situation was clearly desperate, but suddenly one of King Company’s men had an inspiration. After working with the two disabled radios for several hours, Carpenter’s radio man, Private Paul North, realized one antenna is pretty much like any other.

The company still had several small SCR 536 “handy talkies,” although they did not have the range to carry back to battalion. North, however, unscrewed an antenna from a 536 set, tied it to a fence post to get maximum elevation, and jury-rigged a connection to the big SCR 509 using a length of signal corps telephone wire. At about 1 pm, Private James Calhoun of Love Company, the battalion reserve, heard his own SCR 509 come to life. The message was from King Company, and it was, “We made a Touchdown at 0745.” Touchdown was the coded signal for King Company on its objective.

Two companies of M4 Shermans of the 40th Tank Battalion had been waiting to advance in support of the infantry but had never gotten word there was actually infantry left to support. As soon as the radio message was relayed to the commander of 40th Tank Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel John Brown, he ordered his Company A to “forget about bad roads, mine obstacles, and infantry support and get out to Lindern.”

The tanks moved forward, passing south of Lindern, but lost one Sherman to German fire and stalled short of the rail cut. Lieutenant Romersberger of 1st Platoon and his runner, Private Howerton, volunteered to go back, find the tanks, and guide them to King Company’s positions. Although Howerton is officially credited with volunteering, he does not remember doing so and believes Romersberger volunteered, and he simply accompanied him as his runner. Howerton had developed enormous respect for his new platoon leader during the hours of the Lindern battle, and in his own words, “I would have followed him anywhere.”

The two men found six of the Shermans buttoned up on the outskirts of the village and had a hard time getting their attention. The field phones on the back decks were not working, and so Romersberger and Howerton were reduced to banging on the side of the hulls with their rifle butts. “If there had been any German snipers nearby we would have most certainly drawn their fire,” Howerton recalled years later, “but nothing happened. Eventually we roused the tank commander, crawled on his tank and rode back through Lindern like Hannibal crossing the Alps.”

A High Price for Lindern

At 2 pm, the six tanks crossed the overpass and deployed in support of King Company. The sense of elation among Carpenter’s men was indescribable. One of the soldiers in King Company later remembered, “When we saw those tanks, we figured the whole German Army couldn’t drive us out of there.”

The fight was far from over, but from that point on the Railsplitters definitely had the upper hand and did not let it go. Throughout the night of November 29, Love Company, all of 1st Battalion, and most of the 40th Tank Battalion moved forward, cleared Lindern, and formed a perimeter defense. No counterattacks came that evening, but German shelling became heavy.

On the evening of the 30th, and again on the night of December 1, the Germans launched a series of strong counterattacks using battle groups formed from 10th SS Panzer Division and 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung, as well as the 9th Panzer Division, hastily pulled back out of its rest and refit encampment. It was too little, too late, however. The 335th had paid a very high price for Lindern, and no one was ready to give it up. Within days the main German position began to crumble and the balance of the Railsplitters moved forward and secured the plateau overlooking the Wurm and Roer Rivers. After a week or so to rest and reorganize, the Railsplitters would conduct an assault crossing of the Roer.

That, at least, was the plan, and the Railsplitters would indeed force the Roer River against tough German resistance, but they would not get around to it until the end of February 1945. Days before they were to hit the Roer in December, Hitler’s Ardennes offensive, popularly known as the Battle of the Bulge, kicked off, and the 84th Division was shifted south. It played a key role in blunting the German northern offensive arm in the Ardennes.

What was important now was that the Railsplitters had taken everything four German divisions could throw at them, advanced through the strongest fixed defenses the Germans had anywhere, in the worst physical conditions imaginable, and triumphed. And in the end it was not numbers or firepower that made the difference; it was the courage and determination of just 100 infantrymen at Lindern.

After the Battle

After it was pulled out of the line, King Company received enough replacements to bring it close to full strength for the Ardennes. It needed quite a few. Of the 174 officers and enlisted men of King Company who crossed the line of departure at 6:30 am, November 29, 1944, a total of 88 men were killed, wounded, or captured, almost exactly half the company’s strength. The influx of new men, however, did not change the essential character of the company. No matter how hard things got in the Bulge, the solid cadre of “Lindern men” always held the company together and kept it going.

There were some new officers. George Prewitt moved up to command a platoon, receiving his field commission on December 19. He refused to let any of his men salute him or call him sir, though. He still worked for a living.

There were medals, as well. A total of 21 Bronze Stars were awarded to King Company men for the action at Lindern. Lieutenants Romersberger and Pozyck both received the medal, as did Sergeants Prewitt, Matuska, and Humphrey. So did Private Robert Nordli, who stopped a Tiger tank with an M1. Two of the Bronze Stars were awarded posthumously.

Another posthumous Bronze Star went to First Lieutenant Garlington, who had brought forward the only platoon of Item Company to get through. He made it through the initial advance, and showed both courage and initiative in his actions covering King’s right flank, but he was mortally wounded by German artillery fire the following day. Garlington was a graduate of The Citadel, had in fact been the class valedictorian, and great things were expected of him. He did not have long to make good on those expectations, but he made the most of the time he had.

First Lieutenant Leonard Reed Carpenter, the man who led King Company forward and held them together all through that long day, was awarded the Silver Star. He continued to lead King Company during the Bulge, the assault crossing of the Roer, and on into Germany, right up through March 1945, when he was rotated out for 30 days of R&R. The war ended before he returned. Some of the men felt the R&R saved his life; he continued to lead from the front, and, by March, many felt his luck had about run out.

They were wrong, however, and it was not the first time they had been wrong about him. A junior merchandizing executive before the war, a white-gloved, spit-and-polish martinet of an executive officer in stateside training, Carpenter had emerged as a calm, courageous, and resourceful leader in the crucible of combat. There had been a time when no one in the company—except perhaps George Prewitt—would have thought it possible.

On Dec 1 My Father’s (1Sgt Foster Bell) Company, E as part of 2nd Bn 333, was ordered to take the high ground NE of Lindern which they did. F 333 advanced too far and were cut off and captured. They lost 2 platoons after a truce was called in order to remove casualties, but the German “medics” took notes of their positions. E 333 later took up position in an orchard on the East side of Lindern. An account of this is in 2Lt Cobb’s book “War Class” (they did not graduate but were commissioned). He was a classmate of Lt Garlington at the Citadel and a replacement Platoon Leader in E333.

I was able to contact a few of the men who served under my Father and did expensive correspondence with some, particularly Jack Hyland who became a writer for Dick Clark after the war and worked at WFIL in Philadelphia. We emailed 5 times a week for 4 years until he died. I also met him at the reunions and also Alan Howerton and we also corresponded. I miss them a lot

Lt. Creswell Garlington, Jr., was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his gallant actions at Lindern.

https://thecitadelmemorialeurope.wordpress.com/in-memoriam/alphabetical/creswell-garlington-jr/

The photo of the men walking behind the British tank through a ruined neighborhood, I believe, is actually of Co A, 333rd, clearing out Geilenkirchen on 19 Nov 44. My father, James N. Doyle, was a 2Lt of the 1st Plt of Co A in that initial attack. I have visited that neighborhood and the buildings have all been restored. I’m sure it was representative of the neighborhoods in Lindern at the time.

My uncle, PFC WILLIAM G. STAUDT JR, whom I was named after, was KIA on November 29th 1944 in Gereonsweiler Germany. He was part of the 335th Infantry Regiment 84th Infantry Division. He is laid to rest in the American War Cemetery Margraten, Netherlands.