By William Stroock

Controversial, outspoken, and sometimes insubordinate, British Brigadier Michael “Mad Mike” Calvert was also the boldest and most effective commander in Operation Thursday, the daring 1944 British airborne assault on northern Burma.

During the month-long battle, Calvert’s 77th Indian Infantry Brigade established multiple roadblocks astride Japanese lines of communication, disrupted the flow of supplies, and drew some of the best units in the Japanese Army into a fight they could not win.

In the brutal close-quarters fighting that followed––which often involved bayonets, hand grenades, and flamethrowers in the terrible heat and humidity of the spring and summer of 1944––the 77th Brigade destroyed several Japanese infantry battalions. Calvert’s greatest achievement was the taking of Mogaung, a road junction and railhead without which the Japanese could not hold northern Burma.

In December 1941, four Japanese divisions based in Thailand crossed the frontier and drove the British and Chinese out of Burma. By the spring, the British Army had been routed, the Burma Road, China’s only link to the Allies, had been cut, and the Japanese Army rested on the banks of the Chindwin, threatening to invade India. Even in the midst of such an embarrassing defeat, there was never any question about liberating Burma. General William Slim, commander of XIV Army, set about the task of assembling and training an army to retake the colony. Slim also looked for unorthodox ways to strike at the Japanese. One of these was the Long Range Penetration Group (LRPG), in which columns of British soldiers would march or be airlifted behind enemy lines and be resupplied by air, thereby allowing them to operate in Japanese territory without having to maintain a line of communication with the rear.

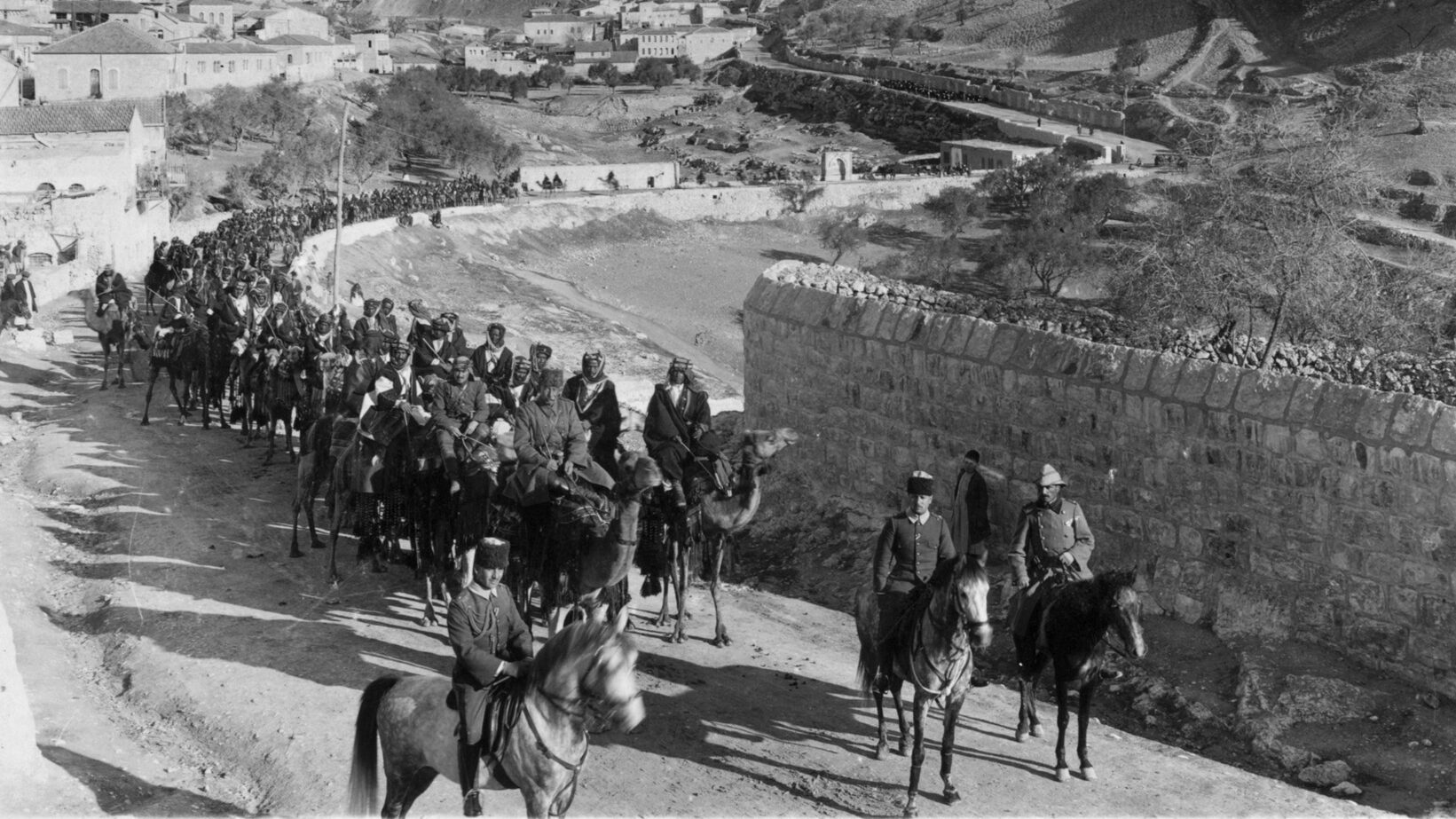

The LRPG was the brainchild of Orde Wingate, a general who already had a great deal of experience in unconventional warfare. When stationed in Palestine in the 1930s, he worked closely with the Haganah, the militia of the Jewish Agency, training them to battle Arab terrorists in small, aggressive groups. He later combined his Haganah paramilitaries with British soldiers to form a trio of units. The Special Night Squads, as Wingate called them, were the bane of Arab guerrillas. They forced the Arabs to stop harassing Jewish towns and British installations in Palestine.

Seeing Wingate’s success in Palestine, in 1940 the Army sent him to the Sudan where he organized Sudanese soldiers and Ethiopian refugees into a special strike group called Gideon Force, which attacked Italian posts in central Ethiopia. Gideon Force’s operation there was highly successful; it took several Italian forts and fought some sharp battles with the Italian Army. “With many of his ideas I was in agreement,” Slim wrote, though he did express skepticism that they could work as well against the Japanese.

Wingate had shown himself to be a good organizer, able tactician, and brave leader of men. As the British position in Burma collapsed, General Archibald Wavell, the British C-in-C in the Far East, sent for Wingate in the hope that he could start a guerrilla war behind Japanese lines.

After touring the front and visiting the summer capital at Myanmo, Wingate went to the Bush Warfare School (a cover name; the school was actually a Chinese training camp) in India, and it was here that he met Major Michael Calvert, the school’s commander. The pair discussed Wingate’s ideas, to which Calvert gave his enthusiastic support. “Once having met, there was no further need to struggle for one’s ideas. He would do the fighting and I would follow,” said Calvert in his memoir, Prisoner of Hope.

Follow he did. Calvert trained the men who in turn trained Wingate’s 77th Brigade in the art of jungle warfare. Later, during Wingate’s first foray against the Japanese, called Operation Longcloth, Calvert commanded one of the two columns that set out from the British base at Tamu, in northeast India in mid-February 1944, and marched through the difficult mountainous jungle and into Burma between the Chindwin and Irrawaddy Rivers.

While the 77th Brigade did little long-term damage to the Japanese during Longcloth, the unit became a sensation throughout the Empire simply because they marched into and fought their way back out of Japanese-held Burma––something thought impossible after the many seemingly super-human feats accomplished by Japanese soldiers during their conquest of Asia. “This first operation proved that the European soldier, as of old, can shake off the shackles of his civilized neuroses and inhibitions and live and fight as hard as any Asiatic,” Calvert wrote.

In the aftermath of Longcloth’s success, Wingate argued for and was given an oversized force of six brigades. Designated the 3rd Indian Division (which he nicknamed the Chindits––a corruption of the Burmese word for “lion”)––the division was augmented by the 1st Air Commando, a wing of several dozen light and heavy transport aircraft and gliders.

For an encore to Longcloth, Wingate concocted Operation Thursday, a bold plan to open a second front in northern Burma. Employing gliders and parachutes, Wingate would drop five of his brigades behind Japanese lines and establish several strongholds. From these strongholds, resupplied by air, Wingate would attack Japanese forces and cut communications all along the railway from Indaw north to Myitkyina.

While Wingate battled the Japanese for control of the railway, the American General Joseph Stilwell would lead a mixed Sino-American force down the Hukawng Valley and take Myitkyina. By taking the town, Stilwell would turn the Japanese right flank and, more importantly from the American point of view, enable the Allies to reopen the Burma Road to China.

Given his close relationship with Wingate and success in Longcloth, Calvert was an obvious choice to command a brigade and Wingate placed the 77th Brigade under his charge. Under Calvert, the 77th Brigade comprised five infantry battalions (3rd Battalion, 6th Gurkha Rifles; 3rd Battalion, 9th Gurkha Rifles; 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers; 1st Battalion, King’s Liverpool Regiment; 1st Battalion, South Staffords, each divided into two columns), an artillery battalion, an antiaircraft battalion, four independent infantry companies, a headquarters company, and company of engineers.

His brigade would be transported in 54 gliders pulled by 26 C-47s to an open field code-named “Broadway” and clear a landing strip. Then the 77th Brigade would “cut all rail, road and river communications of the Japanese 18th Division.” His specific targets were the railway running south of Mogaung, the River Katha, and the road running south from Myitkyina.

The brigade was well equipped for the close-quarters fighting that lay ahead. The men carried small, easily portable 3.2-inch mortars, PIAT antitank grenade launchers, and flamethrowers that would prove invaluable against fanatical Japanese soldiers. He would also have ample air support in the form of American P-51 Mustangs that would be crucial during the campaign. “They used to come over cheerfully again and again [on the radio] with the quiet drawl, ‘What’s the target?’” Calvert wrote of them.

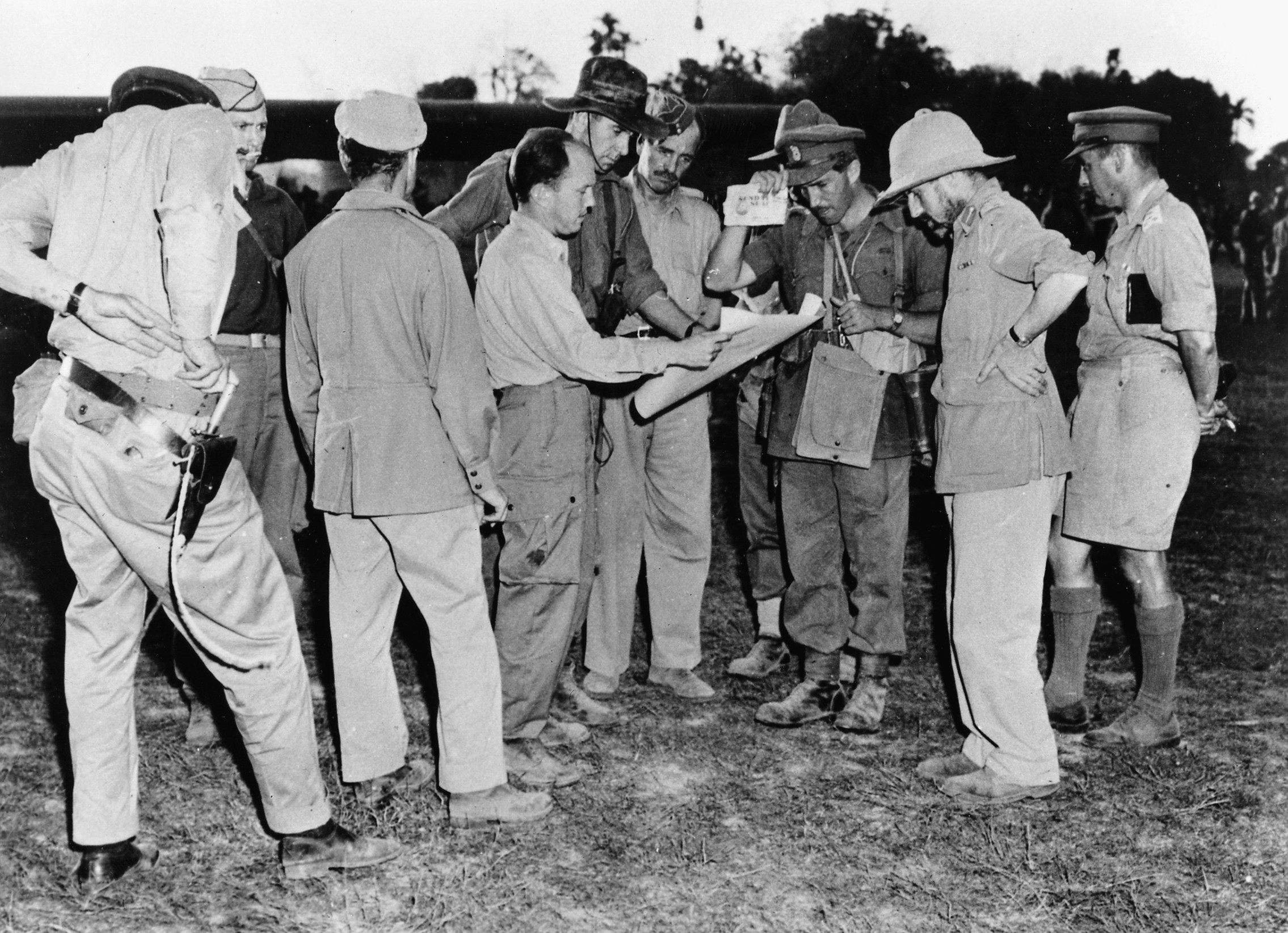

Operation Thursday began on the night of March 5, 1944. Past midnight, the first wave of six gliders took off from India for the Broadway airstrip. Contained inside were 77th Brigade’s headquarters company, a security platoon, and engineers. General Mike Calvert, of course, went in with this spearhead group. The landing was rough and several American engineers were killed. As Calvert got his HQ set up, the surviving engineers went about the task of clearing the gliders, filling in ditches, improving the airstrip, and lighting petroleum flares for the incoming aircraft.

But before the task was complete, the second wave of 54 gliders began arriving, with the result that several gliders crashed into a trio of gliders that had not yet been removed from the landing zone; follow-on gliders crashed into these, causing a massive pileup in the clearing. The end result was 30 killed and 21 wounded. Of the original 54 gliders, only 37 made it to Broadway, with the rest being scattered throughout northern Burma.

But this dispersal was a blessing in disguise. Calvert noted that “the landing of gliders all over North Burma thoroughly confused the enemy, and it was not for some time that he knew our whereabouts and our strength.”

By dawn, Calvert had 350 effectives at Broadway. All through March 6, the American engineers scrambled to get the strip ready to receive aircraft. That night, 63 Dakotas flew in with the rest of the brigade’s support elements, plus four infantry battalions.

As soon as the airfield was established, Calvert set his brigade upon the Japanese. He left Colonel Claude Rome, a trusted subordinate, in command at Broadway with the 3/9 Gurkha. One column (composed of Lancaster Fusiliers) marched east and established a roadblock south of Mohinyan. Another column––the South Staffords and Brigade HQ––established a block in the hills above the village of Henu. The block was a thumb-shaped pocket 100 yards long by roughly 800 yards wide, and the ground outside the block was laced with booby traps and trip wires.

Calvert occupied a good position among several hills, including one featuring a pagoda that overlooked the town. He established his headquarters on a hill to the east; 3/6 Gurkhas remained there with him. Calvert also deployed a “floater company” outside of the stronghold’s defense to bring down on the Japanese during an attack.

Skirmishing began that night as Japanese forces out of Mawlu (5th Railroad Battalion) probed the Chindits’ position; they were easily turned back by a mortar barrage. Heavy fighting erupted the next day and Japanese forces infiltrated the block, getting into Henu and atop Pagoda Hill. From these positions, the Japanese attacked the Staffords’ roadblock.

Calvert personally brought four platoons forward to reinforce the Staffords and then led the combined force in a bayonet charge against the Japanese positions atop Pagoda Hill. To his astonishment, the Japanese rose from their entrenchments and charged down the slope at Calvert and his men. “This definitely was not in the book,” he later wrote.

The British and Gurkhas won the melee in the middle, worked their way up the hill, and easily took the Japanese positions. The Gurkhas then pursued the fleeing enemy into Henu. House-to-house fighting broke out, which the Gurkhas and Staffords ended with flamethrowers.

Calvert’s men suffered 23 killed and 64 wounded in exchange for the destruction of a Japanese battalion. More importantly, the block had been firmly established in the hills east of Henu. Calvert called it “White City,” because of the parachutes hanging in the trees from the first air drops.

The engineers quickly built a pair of airstrips along the railway, one for light aircraft, another for Dakotas. The South Staffords took up positions in the north and east, while the 3/6 Gurkhas dug in along the south, on the river, and west, overlooking the airstrips and railway. Headquarters was on a hill in the middle.

After destroying a railroad bridge north at Mahwun, engaging in some firefights with Japanese forces, and intercepting traffic along the Irrawaddy, the Fusiliers moved west but remained in the jungle outside the stronghold in the role of a “floater company.”

By the night of March 18, elements of the Japanese 53rd Division were coming up from the south and probing White City’s perimeter. But a serious attack did not develop until the 21st, this time in the north. While Calvert was establishing the White City block, the Japanese 3rd Battalion, 114th Regiment and 18th Division had been coming south. The Japanese launched a ferocious assault against the Staffords’ position, penetrating it in two spots and establishing outposts within the perimeter. These held on even as the rest of the assault was turned back.

A few hours later, the Japanese attacked again. As the attack developed, Calvert ordered the floater company to hit the Japanese in the flank. The Japanese were prepared for such a move and threw the counterattack back with heavy losses. Calvert then brought forward a pair of flamethrower-armed platoons. These rooted out the Japanese outposts and stabilized the line.

As the Japanese reformed a few hundred yards to the north, Calvert called a Mustang airstrike down on them. The strikes inflicted heavy casualties and prevented the enemy from renewing the attack. Instead, they withdrew to the north.

Captain W.F. Jeffrey, a platoon commander with the Fusiliers, wrote that the Japanese “used the same approaches night after night, which greatly helped our mortar crews.” The Japanese had been badly mauled in the first serious attack; prisoners revealed that most of their officers had been killed. Calvert lost 36 dead and 42 wounded in the engagement.

Having stopped the Japanese assault on White City, Calvert elected to attack enemy positions to the south at Mawlu. The village was defended by a company of the 2nd Battalion, 113th Regiment––part of the 18th Division. On the village’s right flank was a series of rice paddies. To the south was the village of Sepein.

Two columns, one from the Staffords, the other from the Gurkhas, marched south while a third, the Lancaster Fusiliers, occupied the east end of the rice paddies. The plan was for the main attack force to drive the Japanese out of the village and into the Fusiliers’ position.

The ensuing night attack went well, with the two northern columns driving the Japanese out of the village. As planned, they fled into the rice paddies where they came under withering fire from the Fusiliers. Despite the heavy casualties, the Japanese were able to extract themselves from the paddies and head south.

When their comrades retreating from Mawlu arrived in Sepein, Japanese troops there panicked and fled; the two groups retreated all the way to Indaw, 25 miles down the rail line. Calvert noted, “We now occupied the first sizable Burmese town to be retaken from the Japs.”

While Calvert was consolidating his position at White City, the original landing area at Broadway came under heavy Japanese attack. Broadway was defended by the 3/9 Gurkhas, six 40mm Bofors antiaircraft guns, and five Spitfires that had been specially flown in for the task. A series of large Japanese air raids, some numbering as many as 30 aircraft, commenced on March 17. The Spits and Bofors shot down five aircraft on the first day.

The attacks continued for several days and the Japanese were able to do light damage to the aircraft at Broadway but, because of the hard work of the engineers, were unable to permanently wreck the airfield. Despite the air attacks, reinforcements for the defenders did not stop. The 6th Nigerian Rifles and one battalion from the 111th Brigade were flown in and sent on down the rail line.

On the night of March 26, local Kachin tribesmen reported that a Japanese battalion, later identified as part of the 18th Division, was closing in from the north. Major Rome sent half a platoon north to find the approaching Japanese. When they located them the next day, the platoon laid an ambush that inflicted several casualties. The platoon then pulled back inside Broadway’s defenses.

The Japanese fought back with a major attack that night, hitting the defenses in various places along the northern perimeter. However, they were unable to battle their way through the Gurkhas. Near dawn, two platoons from the floater company arrived on the scene. Their counterattack forced the Japanese to temporarily pull back. Elements of the King’s Liverpool Battalion also arrived but ran into stout resistance from well-entrenched Japanese infantry.

The Brits attacked again that day, this time with flamethrowers in the lead. The Japanese pulled back into the jungle having suffered more than 200 casualties in the course of the fighting. The King’s pursued but were unable to catch up to them. Still another battalion from the elite Japanese 18th Division had been badly mauled.

Calvert followed up his victory at Broadway with an attack on Sepein, calling it “a nodal point in the enemy’s organization for his attack.” The town was a road-and-rail hub and headquarters for Japanese operations in the vicinity of White City. The attack was executed in stages, with the 3/6 Gurkhas seizing a pair of Japanese-held villages between White City and Sepein. Then, the village of Thayaung, farther east, was taken by the Fusiliers.

At dawn on the 13th, the 3/6 Gurkhas struck the town proper. Supported by 25-pounder guns based in the stronghold, the Gurkhas initially made good progress, advancing to the village outskirts where the Japanese had several trenches among the thick brush. The Gurkhas were unable to advance further. Air strikes and a follow-up attack by the 45th Reconnaissance Regiment (which had been loaned from the 16th Brigade) were also unable to dislodge the Japanese.

With no more reserves to commit (after the initial success, Calvert dispatched his Nigerians south to Mawlu), Calvert broke contact and pulled back to Thayaung. Overall, the assault force lost 16 killed and 35 wounded. Calvert contented himself with establishing a temporary block to the north in the vicinity of Tonlon.

Trouble now loomed to the south, where the Japanese 24th Mixed Brigade had fought past Chindit forces (14th Brigade) outside of Indaw and pushed north to the outskirts of White City. The stronghold was now defended by the 12th Nigerian Battalion, which threw back a concerted Japanese effort, counterattacked, and pursued them into the jungle.

On the morning of April 17, Calvert set out from Thayaung with the Reconnaissance Regiment and the 3/6 Gurkhas in the hopes of getting behind the Japanese and pinning them against White City. Calvert struck on the 18th, with the Reconnaissance Regiment leading the way and pushing north until they reached a small stream called the Mawlu Chaung (river). With the Japanese pinned in place, Calvert sent one Gurkha company each around the right and left flanks, but both of these efforts were stopped by fanatical Japanese resistance.

Now it became a slug match, with the Reconnaissance Regiment pushing its way across the stream against fierce Japanese opposition. The Japanese counterattacked, hitting the Gurkhas on the right flank and nearly breaking them. Only a Mustang strike and Calvert’s appearance on the battlefield prevented a complete rout. After this, Calvert decided to pull back.

The brigade had suffered about 70 dead and 150 wounded, though they had stopped the Japanese attack on White City. “The Japs never attacked the block,” he wrote. Several hundred Japanese bodies were found on the battlefield. “The Japanese morale after that, coupled with the effect of our counterattack, wilted right away, and they started to straggle back.”

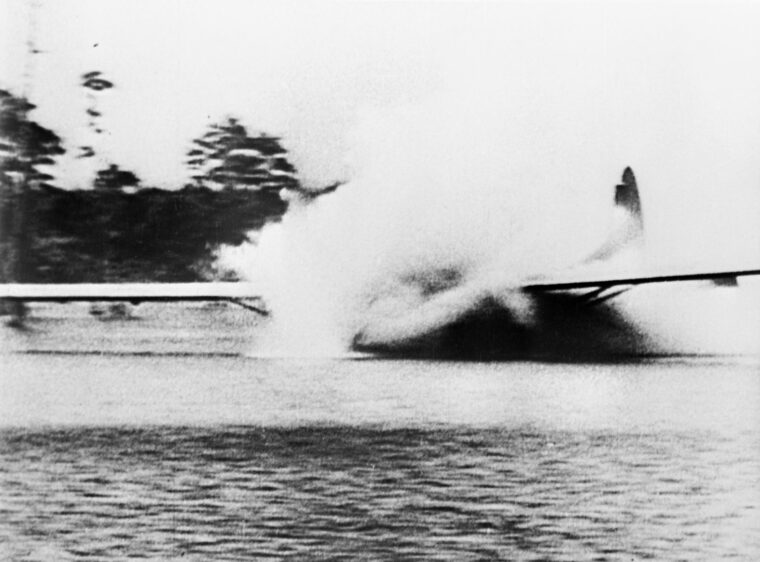

Though it had virtually destroyed the Japanese 24th Mixed Brigade, the battle for White City had sapped the strength of the 77th Brigade. As the 14th Brigade had failed to take Indaw, General Joe Lentaigne, who had taken command after Wingate was tragically killed in a plane crash on March 24, felt that Calvert should abandon White City and Broadway and move north to the vicinity of Mogaung. The town was a road-and-railhead about 20 miles west of Myitkyina and by taking it, Lentainge hoped to aid Stilwell, who had slowly pushed his way southeast against a determined Japanese resistance.

Calvert detested the idea. His 77th Brigade was exhausted from several weeks of hard fighting and, in his opinion, should have been flown out of Burma. Calvert sent several messages to Lentaigne protesting the order which he said was “borderline insubordinate.” Lentaigne had to threaten to remove Calvert to get him to shut up.

The attack was to be a two-pronged effort. The 111th Brigade would establish a stronghold south of Mogaung, called “Blackpool,” to block reinforcements while Calvert and 77th Brigade would attack the town from the east (this stronghold would not figure on the final push on Mogaung, as the Japanese brought much pressure to bear and forced the 111th Brigade to abandon it). He would have help, though, as a Chinese infantry regiment was ordered south from Mytikyina.

White City was turned over to the 14th Brigade and elements of the 3rd West African Brigade while Calvert, still fuming over Lentaigne’s order, moved north. By early May, he was in the vicinity of Mogaung with his three battalions deployed in an arc south of the town. Across the valley was the new stronghold of Blackpool and the 111th Brigade. The stronghold was placed on the east bank of the Namyin Chaung and bracketed in the north by the village of Loilwaw and in the south by the village of Pagunyang. To the east was a sharp ridgeline. Between the two lies an open plain, the road and rail line to Mogaung. Just east of the rail line, on the banks of the Wetthauk Chaung, lay the village of Pinhmi. A second road to Mogaung ran through the village. The Pinhmi Bridge, northwest of the village, was the only way across the river.

Knowing that the Japanese were expecting an attack from the south, Calvert, on the advice of Major Rome, sent a couple of battalions east around the Japanese flank. Calvert left a company and an RAF spotter at the village of Lamai from which the whole valley could be observed. The force slowly worked east, village by village.

On June 1, they seized the village of Lokum at the base of the ridge’s east slope. The next night they pushed on to the village of Ngakahtawng. From there, Calvert sent a platoon north to the Tapaw ferry on the Mogaung Chaung to secure a crossing for the Chinese.

Calvert now had a strong screen east of Mogaung. The next task was to push up the ridge. By then, however, it was strongly defended by a Japanese infantry company. Calvert’s attack began on the night of June 2. As the Staffords and Gurkhas started up the ridge, they were met by heavy fire that temporarily stopped the advance. One platoon of Fusiliers managed to reach the crest and rolled up the Japanese flank while the rest of the battalion moved up with machine guns and brought the enemy positions under fire.

One platoon commander with the Fusiliers described the fighting: “We took the ridge, then the next, and the next, and so we continued all day, loading and unloadin’, marching and fighting.” With mortars and PIAT grenade launchers, the British systematically cleared out the ridge as far north as Lokum, about halfway to the Mogaung Chaung.

Considerable obstacles still lay ahead. The ground between the ridge and Mogaung was marshy. A river named the Wettauck Chaung ran through the center. At the foot of the ridge was the village of Pinhmi and, beyond, the crucial Pinhmi Bridge.

There were several smaller villages as well. From north to south these were Naygygion, Ywathitkale, and Mahaung (south of Mogaung). All were occupied by the Japanese. Calvert planned to come down from the ridge and push his way across the Wettauk Chuang via Pinhmi. The first task was to clear the rest of the ridge. Calvert mounted a two-pronged assault, with the Staffords running along the crest of the ridge while the Gurkhas advanced along the east slope. A night of heavy fighting cleared the ridge for about a quarter of a mile north, until they were opposite Pinhmi. Next, Calvert advanced north to Gurkha Village (an old land grant village given to Gurkha soldiers in the 19th century); the village was taken without incident. The way to Pinhmi was now open.

In preparation for just such an attack, the Japanese had dug a series of bunkers under Burmese homes, and also on the west bank of the river. These preparations would prove to be all for naught.

The Fusiliers launched the first attack on Pinhmi. They spent the night fighting their way through the jungle scrub, only reaching the village outskirts by the next morning. The next day was spent clearing Pinhmi. A hospital, ammunition dump, and several prisoners were taken during the effort.

With the village in friendly hands, Calvert ordered a frontal assault on the bridge. The Fusiliers suffered heavily and had to pull back to Pinhmi. Calvert later wrote simply, “I should not have ordered this attack.” A few days later, the Gurkhas gave the bridge a try. The Japanese repulsed the first attack, but a second effort succeeded. While one company attacked the bridge head on, a second company waded through waist-deep marsh to the south and around the Japanese flank. The bridge and village had at last been captured, but the attacks on Pinhmi cost the 77th Brigade 130 dead and wounded.

There were still two important Japanese positions to take: the Court House Triangle, an enemy position just up the road from the Pinhmi Bridge, and Naugkyaiktaw, a Japanese-held village about 400 yards down the river. The job fell to the Fusiliers who pushed the enemy out of the triangle after a day of heavy fighting.

At the same time, the Staffords launched an attack down the banks of the Wettauk Chaung. The attack secured 77th Brigade’s southern flank, enabling Calvert to plan for a further advance on Mogaung. He did not attack right away though. Instead, he dug in his tired battalions (they were down to a combined strength of about 550) along the Wettauk Chaung and ordered them to harass the Japanese with aggressive patrols in the no-man’s-land between the two forces and even into Mogaung proper. “We usually got the best of these night encounters,” Calvert said.

This phase of the fighting culminated with a night attack on Naugkyaiktaw. The assault opened with a mortar barrage and ended with the aggressive use of flamethrowers against dug-in Japanese. Calvert’s machine gunners mercilessly cut down the enemy as they tried to flee north. “We joined the shooting, standing on chairs to kill off any Japs seen crawling away,” he noted.

As Calvert contemplated how to attack Mogaung, the promised Chinese reinforcements finally arrived. These were the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 114th Regiment. The 114th was a well-trained and battle-hardened force ably commanded by a colonel named Li who worked closely with Calvert during the upcoming attack. Li’s first action was a successful attack on the village of Loilaw. It was “a sharp little engagement,” in Calvert’s words, which gained the town and several of the enemy’s antiaircraft guns and trucks.

With the southern route now open, Calvert ordered a two-pronged assault. The Gurkhas would advance along the Mogaung to the railway bridge while the Staffords pushed through toward the rail embankment in the center of town. The Fusiliers and flamethrower unit stood in reserve. The Chinese would attack from Loilaw.

Calvert softened up the Japanese in Mogaung with mortar barrages and air strikes; 70 sorties were mounted on one day alone. Then, in the early morning hours of June 23, the attack got under way. As they advanced across the open ground, the British suffered heavy casualties. Even so, the Gurkhas took the railway bridge, but had to leave several Japanese strongpoints behind. These were dealt with by flamethrower teams, who literally poured fire into the tight bunkers.

By dawn, the Staffords had reached the embankment but came under heavy fire from the left, as the Chinese had made only a light probe and failed to follow this up with a concerted assault. Calvert ordered the Fusiliers into the fray and brought all his machine guns and mortars to bear on the Japanese. Under this cover fire, the Staffords closed with the Japanese positions and systematically cleared them out, using PIATs to blow holes in the occupied house; hand grenades and flamethrowers followed.

Despite being cut off, the Japanese in the west of Mogaung, supported by mortars on the far river bank, fought on. Calvert called in air support on the various bunkers. He unleashed a pincer attack on the 25th, with the Fusiliers advancing from the east while the Chinese came up from the south. The Fusiliers pressed their attack but were turned back in no small part because the Chinese gave up the attack early on. Calvert later learned this was a clever ruse by Li, who left two men behind in the rubble. All night the pair watched the Japanese positions, noting when and where men emerged for meals and other needs. By morning, they had pinpointed every Japanese bunker. Armed with this information and their deadly flamethrowers, the Gurkhas cleared out the rest of Mogaung over the course of the next two days.

After the fall of Mogaung, the 77th Brigade was down to 300 able-bodied men and was finished as an effective fighting force. Calvert handed the town over to Colonel Li and hoped to get his troops back to India. Incredibly, General Lentaigne ordered Calvert to send a company down the rail line to Hopin, but Calvert flat out refused to do so.

Then Stilwell demanded that Calvert send his few remaining troops to help the Marauders at Myitkyina. When Calvert said he couldn’t, Stilwell, true to his nickname of “Vinegar Joe,” accused Calvert and his men of malingering or worse. Calvert eventually met with Stilwell and smoothed things over. Soon thereafter, the battered, exhausted men of 77th Brigade were flown out of Burma for a well-deserved rest.

Having established several blocks, destroyed at least five Japanese battalions, and taken Mogaung, Calvert’s 77th Brigade was easily the most effective Chindit force.

Of the final victory at Mogaung, Calvert simply wrote, “Elation! I had no elation, no satisfaction, no positive emotion––just to lie down for a while and rest.”

Calvert returned to England in 1945 for medical reasons. His postwar career was rather checkered. He commanded an SAS Regiment during the Malay Emergency but saw little success there as his troops were poorly selected and of questionable loyalty.

Calvert was then posted to Germany where his wild, alcohol-fueled conduct led to a charge and court-martial conviction for “gross indecency with male persons,” though it should be noted the evidence used in his trial is highly suspect. After leaving the Army in 1952, he wrote extensively on guerrilla warfare and the Chindit campaigns in Burma. He died in 1998.

Of Calvert, the British historian John Keegan said, “Calvert was a great warrior who was also opinionated, dangerously outspoken and, at times, verging on the insubordinate. His men loved him; the military establishment did not.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments