By David H. Lippman

The “Pearl of the Orient” had lost all of its luster by January 1945.

Three years of brutal Japanese occupation had left many of Manila’s 800,000 native residents humiliated, tortured, or dead. The city’s economy was in shambles. American and British citizens living and working in the Philippines—some as young as 12-year-old Sascha Weinz- heimer—were imprisoned in conditions of starvation and utmost cruelty in Santo Tomas University Internment Center (STIC) and Bilibid Prison.

Japanese troops guarded nearly every intersection and did not hesitate to smack Filipinos if they failed to bow properly. That included Filipino women, who were highly regarded in Manila’s society. Starving Manilenos robbed graves looking for jewels to sell for food.

Though starving and humiliated, Manila’s residents could still gaze upon one of the miracles of the war: the Philippine capital and its architecture—a mix of renaissance Spain and 20th century America—was still intact. When the Japanese invaded the Philippines in 1941, General Douglas MacArthur had declared Manila an “open city,” withdrawing troops to spare it from heavy Japanese bombing.

Three years later, the historic Spanish fortress of Intramuros with its massive walls and giant dungeons was still pristine. So were enormous American structures like the Legislative Building, the Finance Building, the Agricultural Building, and the Malacanang Palace—all designed by Daniel Burnham, who had created New York’s Flatiron Building and Washington’s Union Station. The Manila buildings were created in the heavy Roman style that the Americans used for their official structures back home. These buildings impressed Manilenos as symbols of authority and power.

The grand structures could also become superb defensive positions, something the Japanese resorted to when, on October 20, 1944, MacArthur grimly waded ashore at Leyte Island in the southeast Philippines, keeping his promise to return to the archipelago. There was no question that his troops, after conquering Leyte, would head for Luzon, the Philippines’ main island, to liberate it and Manila.

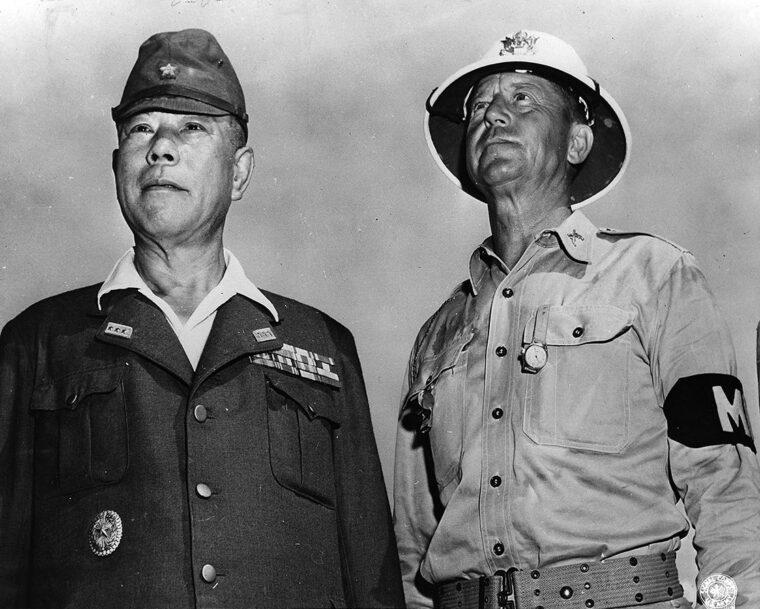

To prevent that, the Japanese sent in one of their best officers, General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who had conquered Malaya and Singapore in 74 days in 1942. Since then, because of official jealousy, he had languished in Manchuria. Now he was needed back in the field.

With only 275,000 men and no air or naval support, Yamashita soon realized that preventing an American invasion of Luzon was an impossible task. The U.S. dominated the seas and skies. They could outmaneuver him and had more soldiers. The best he could hope to do was keep his troops in the field long enough to support Japanese negotiations with the Americans to achieve a peace that would leave his country in possession of the archipelago.

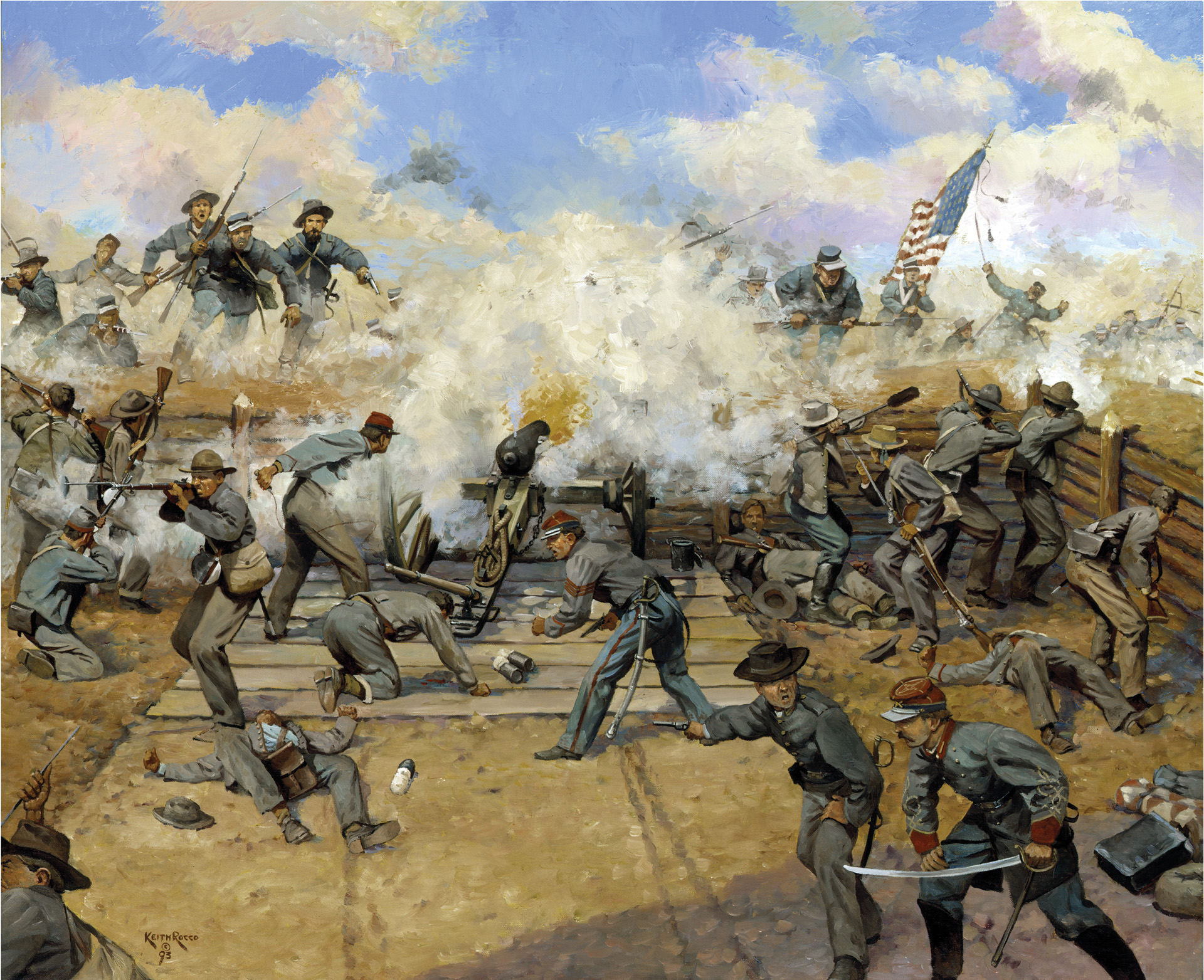

The American assault came precisely where the Japanese had attacked in 1941—at Lingayen Gulf, on January 9, 1945. This invasion saw 200,000 Americans of the U.S. 6th Army go ashore, backed by Navy and Army Air Forces fighters and bombers, and Admiral William Halsey’s 3rd Fleet. The Japanese offered limited ground defense to the seaborne assault.

German-born Lieutenant General Walter Krueger, commander of the 6th Army, was no stranger to the Philippines, having served there as an enlisted man during the 1899-1901 Insurrection.

When war broke out, MacArthur asked for Krueger as an army commander, and he was sent to Australia to build the 6th Army. He launched successful invasions of New Guinea, capturing key towns and ports. Next up was Leyte, and while the invasion went in properly, it turned into a plodding drive in heavy rains. When Leyte was finally secured, the 6th Army loaded up for the assault on Luzon and, once ashore, started moving steadily and cautiously south.

Recognizing that his men could not counterattack Krueger’s tanks, artillery, and troops without frittering away their lives and Luzon, Yamashita divided his forces into three groups—none of which would actually defend Manila. He would impose upon the Americans the humanitarian duty and logistical nightmare of feeding its population of nearly a million people.

Yamashita’s first force, the Shimbu Group, 80,000 strong, would dig in amid the mountains east of Manila. Numbering 30,000, the Kembu Group was to occupy hills 40 miles north of Manila, and deny the Americans the use of Clark Field, the Army Air Forces’ great pre-war air base. Finally, Yamashita would command the Shobu Group, with 152,000 men and all the armor, in the rugged northeast of Luzon.

That left the city of Manila. Yamashita wanted the capital abandoned, but Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi—who did not answer to Yamashita—refused to withdraw his 31st Naval Special Base Force from Manila. Iwabuchi could muster some 12,500 men to defend the city. The Japanese used their sailors as marines and infantrymen, so they were trained in that role. Iwabuchi also prepared Manila’s defenses with all the energy and fanaticism the Japanese could offer, with pillboxes, machine-gun nests, and artillery—they even knocked down the tall coconut palms on Dewey Boulevard along the harbor coast to slow down the attack.

At least Iwabuchi didn’t have to worry about a seaborne assault on Manila. Japanese troops still occupied Corregidor, which had been America’s last foothold in the Philippines, and it was well defended. Facing the three dispersed Japanese army groups and occupied Manila, Krueger was forced to divide his men. Two divisions headed northeast to take on Yamashita’s Shobu Group. Another advanced cautiously to take on the Kembu Group.

MacArthur was furious over the pace of Krueger’s assault. He wanted Manila liberated by January 26, his 65th birthday, but the triumphal parade he had planned would clearly not happen. In addition, he wanted to liberate the American prisoners, out of pure sentimentality—many of them had served under him on Bataan.

On January 31, MacArthur visited the headquarters of the 14th Corps, under Major General Oscar Griswold, and ordered him and the newly-landed 1st Cavalry Division, under Major General Vernon D. Mudge, to do the job. MacArthur was blunt: “Go to Manila! Go around the Nips, bounce off the Nips, save your men, but get to Manila! Free the internees at Santo Tomas. Take the Malacanang Palace and the Legislative Building.”

MacArthur had given the job to the right division. The 1st Cavalry was “dismounted,” meaning that its troopers fought as infantry, and they had done so with energy and ferocity in New Guinea and Leyte. Its regiments included the legendary 7th Cavalry of Custer fame, which would play a major role in the assault.

MacArthur wanted Mudge to make a 100-mile dash through enemy lines without any reconnaissance or flank protection, with three flying columns of blacked-out, all-arms groups. The attack would go in at one minute after midnight on February 1—flying columns racing ahead—the rest of the division following.

Unhappy with Krueger’s plodding nature, MacArthur also wanted the 37th Infantry “Buckeye” Division, under Major General Robert S. Beightler, to drive south on the 1st Cavalry’s right flank. The Buckeyes were an Ohio National Guard outfit, and Beightler’s pre-war job had been the state’s transport director. However, the 37th lacked transport—its GIs had to slog down dusty roads in Luzon’s humidity 150 miles to Manila.

Yet the race was not just between two divisions from the north. Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger’s 8th Army was tasked with liberating South Luzon and the rest of the archipelago, turning the attack into a pincer assault. On January 31, paratroopers of the 11th Airborne Division, commanded by Newark native Major General Joseph Swing, came ashore from landing craft at Nasugbu, 30 miles southwest of Cavite, just south of Manila.

MacArthur wanted this base seized; he also wanted Manila surrounded. The airborne troops would have to move fast on their own feet to cross the vital Palico River Bridge over a 250-foot gorge before the enemy detonated it. They did, coming astride a paved, two-lane road to Tagaytay Ridge, which was taken by the 511th Parachute Regiment after a difficult airdrop. From there, the 11th could look down on the Cavite Peninsula and Nichols Field, with its enemy pillboxes, some three stories high.

Supported by Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters and Douglas A-20 Havoc attack bombers, the 11th attacked Nichols Field immediately, facing Japanese naval troops whose defenses bristled with weaponry. The Japanese counterattacked with the usual ferocity, getting chopped up by American .50-caliber machine guns. The 11th Airborne’s hopes to be first into Manila ended with 900 casualties on Nichols Field. The division was turned over to 6th Army’s 14th Corps for better coordination.

On February 17, the paratroopers attacked Fort McKinley, seizing the old bastion and killing 5,210 Japanese. They had prevented Iwabuchi’s men from escaping the closing trap, but the victory ended their role in the Luzon campaign.

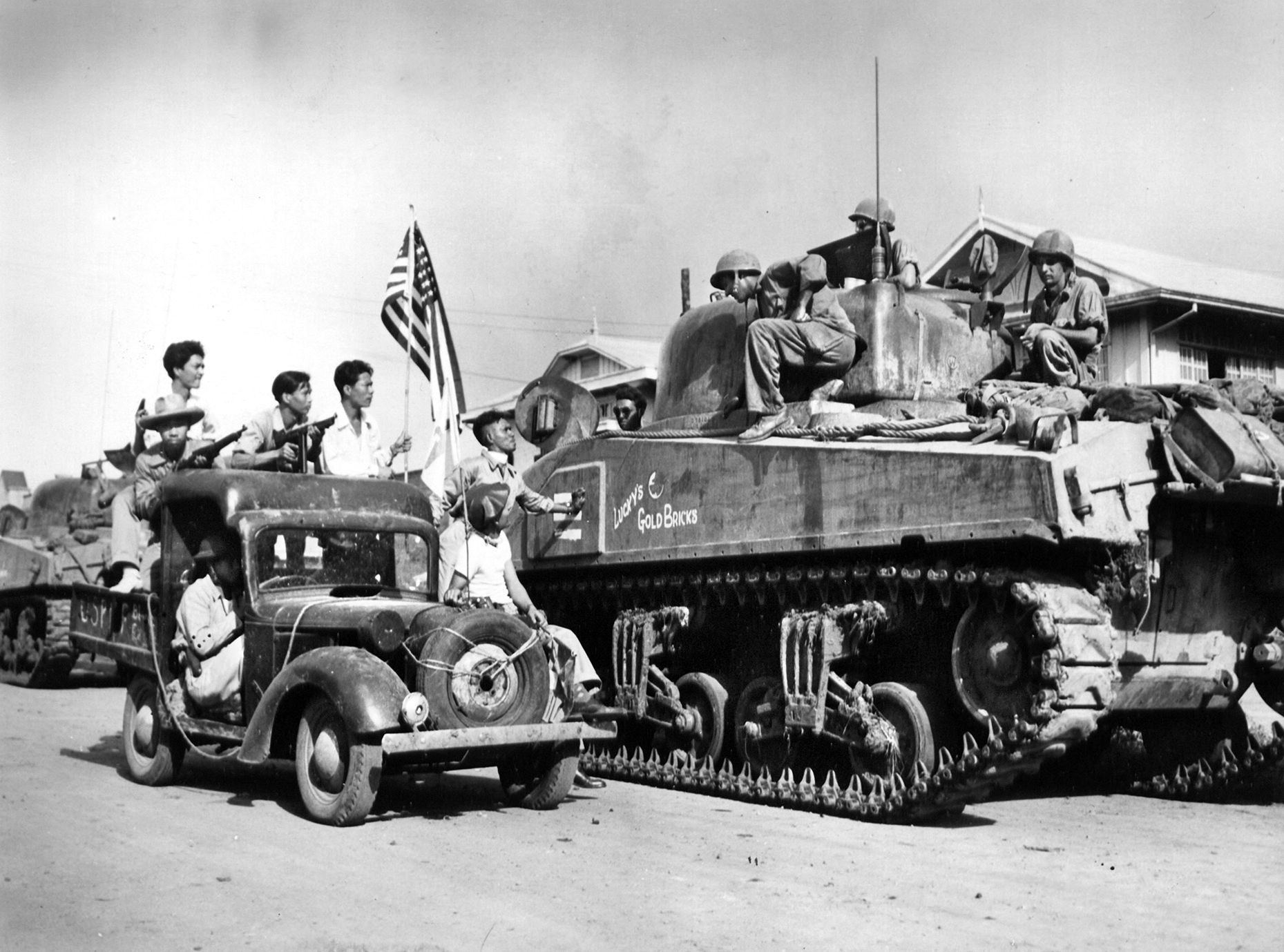

Averaging 15-20 miles an hour, the 1st Cavalry Division continued driving south—liberating a POW camp at Cabanatuan in a daring raid that saw only one casualty—and was the first to reach Manila on February 3. A few hours later, the 37th Infantry broke across the city limits.

First up was the Malacanang Palace, guarded by the Japanese puppet government’s all-Filipino Presidential Guard Battalion. They were delighted to see the Americans back and greeted them. Next was the Legislative Building, on the south side of the Pasig River, 190 yards southeast of Intramuros. The Cavalry met fierce resistance as they approached the Pasig. They were ordered instead to liberate the 3,800 prisoners at STIC.

The university was surrounded by a 12-foot concrete-and-stone wall, perfect for keeping prisoners in. The Japanese filled the classrooms with captured Allied personnel from all walks of life. Among them were 900 children, including Sascha Weinzheimer, the polio-ridden daughter of an American plantation manager.

Also held at STIC was a collection of U.S. Army nurses bagged at Bataan, who suffered with the added burden of struggling to care for their fellow prisoners.

The camp’s executive officer, Lieutenant Abiko, cut rations in 1944 and ordered prisoners to build barbed-wire defenses. All prisoners began suffering from the various diseases connected with malnutrition. Abiko was universally hated for his sadism. Sascha and her family lived in one of many shanties in STIC’s courtyard, which gave them a grandstand seat when U.S. aircraft began bombing Manila on September 21.

When Christmas came, rations were cut again—everybody was hungry. The average male had lost 51 pounds, the average woman 32. By January, rations were down to 700 calories a day. The Japanese doctor would not let the Allied medical staff write “malnutrition” or “starvation” on death certificates, denying such conditions existed. The American doctor Theodore Stevenson, who refused these orders, was dragged off to a separate jail and put on his own starvation diet.

As American troops came closer, the Weinzheimers’ shack swayed from the bomb concussions. Parents asked their kids to drop to their knees and say to guards, “Nice Japanese, I like you. Give me candy. Give me sugar.” If a sentry didn’t like the gesture, he would push the child off. One child coaxed a banana out of a guard because her father had been killed at Cavite in 1941.

On February 3, Iwabuchi ordered his men: “You must carry out effective suicide action as members of special attack units to turn the tide of battle by intercepting the attacking enemy at Manila.”

At STIC, the prisoners could see a memorable red sunset as American bombers attacked Japanese defenses and American artillery rounds detonated. Sascha said later, “It was like throwing a rock at a beehive and having it come alive.”

At 6:30 p.m., the camp lost power. At about 9 p.m., two umbrella flares lit up the dark STIC and a tank crashed through the front gate. The top hatch of the lead tank, named “Battlin’ Basic,” popped open and its commander shouted, “Hello, folks! We’re Americans!” As the five tanks from the 44th Tank Battalion clanked into the compound, sending Japanese guards fleeing, an elderly woman asked a GI, “Soldier, are you real?”

“Yes, I reckon I am,” the American responded laconically.

Incredibly, Lieutenant Abiko ran in front of “Battlin’ Basic,” brandishing his Samurai sword and pistol, a pouch of suicide grenades on his shoulder. The GIs gunned him down.

About 63 Japanese guards held out, fleeing to the Education Building, pursued by the liberators. The Japanese held 267 internees as hostages. Unaware of those hostages, one of the tanks opened fire on the building. A woman shouted from a STIC window, “Stop it. Stop it. My husband and son are in there.” The troops ceased fire.

Rather than endanger the hostages, the 1st Cavalry dug in for the night, waiting for Brigadier General William Chase to arrive to lead negotiations. As dawn broke on January 4, internees in the Education Building leaned out windows and begged for relief. They also smelled the bacon and eggs the GIs were cooking and asked for food.

Chase spent the day exchanging messages across the line with the senior Japanese officer, Lieutenant Colonel Toshio Hayashi, with Lieutenant Colonel Charles E. Brady and his waxed mustache going back and forth. Hayashi greeted Brady with his hands on his twin holsters. Brady nervously twirled his mustache.

Hayashi demanded “safe conduct with honor” to release the hostages: his men had to be allowed out with full arms and ammunition. Finally, they reached an agreement. The Japanese could keep their personal weapons, but no grenades or machine guns. At daybreak on February 5, marching three abreast, the Japanese left, going past Brady’s men, scrambling for cover when they neared their own lines.

But the Battle of Manila had only just begun. In addition to the casualties 1st Cavalry had suffered in the drive, more were coming in. The relief column brought army doctors and medics, who asked the liberated nurses to help out in a temporary hospital, set up in the Education Building. Despite being weak and faint from hunger, the liberated nurses were energized by adrenaline and turned to.

The nurses, veterans of Bataan and Corregidor, knew their trade of changing bandages and giving medications, but soon discovered that science and history had passed them by. Asked by a doctor to fetch some “penicillin,” Nurse Rita Palmer had no idea what the man was talking about. Nurse Rose Rieper was astonished by the GIs’ K-ration packs, and asked a soldier if she could eat one.

“Ma’am, if you’ll eat that, you must be hungry,” the GI answered.

Meanwhile, the 37th Infantry began driving toward the Pasig and Bilibid Prison, where more internees were held. As they did, the Japanese dragged scores of Filipino civilians to the Pasig’s estuaries, where they bound them, bayoneted them, shot them, and slashed their throats and bellies. More than 100 civilians were either left to rot or had their bodies burned.

The 37th Infantry’s 148th Regiment drove into Manila, and the 2nd Battalion, 148th Infantry, liberated a highly desired objective—the Japanese-owned Balintawak Beer Brewery. The 2nd and 148th were delayed in their advance while the division’s engineers built a bridge over the Tullahan River, so the battalion took advantage of the break for a beer party.

On February 4, the 2nd/148th reached Bilibid Prison. Here, the Japanese commander, Major Ebiko, packed up with his men and left behind some food and medicine, posting a sign: “Lawfully released Prisoners of War and Internees are quartered here. Please do not molest them unless they make positive resistance.” The 37th freed 447 civilians and 828 military prisoners.

With the 37th and 1st Cavalry menacing northern Manila, Colonel Katsuzo Noguchi, commanding the Northern Sector unit of the Manila Naval Defense Force, started demolishing buildings with explosives to narrow the American advance to areas that were covered by pillboxes and machine-gun nests. The 37th found a blazing city and heavy enemy fire.

Incredibly, because of the liberation of Malacanang and the prisoners, the American media proclaimed Manila liberated and the battle over. MacArthur would write the same in his memoirs shortly before his death in 1964.

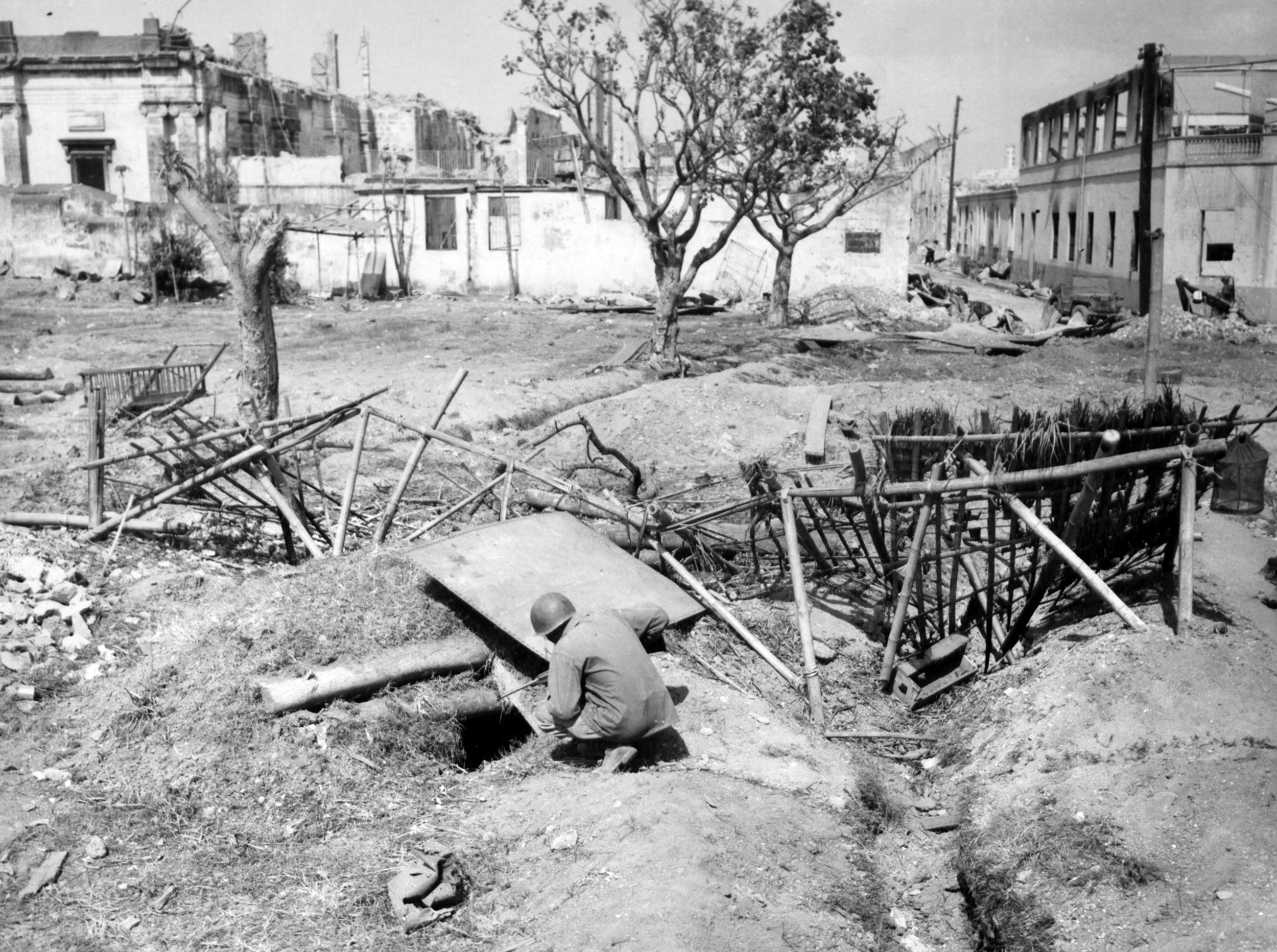

Griswold and Krueger were opposed to indiscriminate artillery bombardment on the inner city, knowing it would only endanger a million innocent Manilenos and provide the Japanese defenders with more cover. Artillery could only be called down on a tightly defined target. For the same reason, air support was banned.

The 14th Corps’ first objectives in the city were its water and power plants. The 7th Cavalry grabbed the water plants, east of Malacanang Palace, but the powerhouse was on Provisor Island in the middle of the 150-yard-wide Pasig River, and all the bridges across it had been blown. The 129th Infantry Regiment crossed the river in small boats and came under heavy Japanese fire, losing three boats. For three days, the 129th slugged it out with Japanese sailors. Griswold begged for artillery support and finally got it. On the 11th, at a cost of 300 GIs, the island was taken, but the power plant was wrecked—Manila would have no electricity for some time.

The 148th rode the 672nd Amphibious Tractor Battalion’s vehicles across the Pasig to clear the Pandacan district and met more resistance around the railroad station on February 9. The 800 men of the Central Force’s 1st Naval Battalion refused to retreat or surrender, so artillery was called in to turn the area to rubble.

The 148th attacked the station, but Japanese fire pinned them down. Privates John Reese, Jr., of Oklahoma and Cleto Rodriguez from San Antonio, continued forward to a house 60 yards from the objective. They spent an hour killing up to 60 Japanese. They moved forward again, killing more enemy troops for a total of 82. When they ran out of ammunition, they tried to return to their platoon, but Reese was killed. Both were awarded the Medal of Honor, Reese posthumously (Rodriguez died in 1990).

The 37th Division could now resume its advance despite losing 19 dead and 216 wounded on February 9—more than in the entire Luzon campaign.

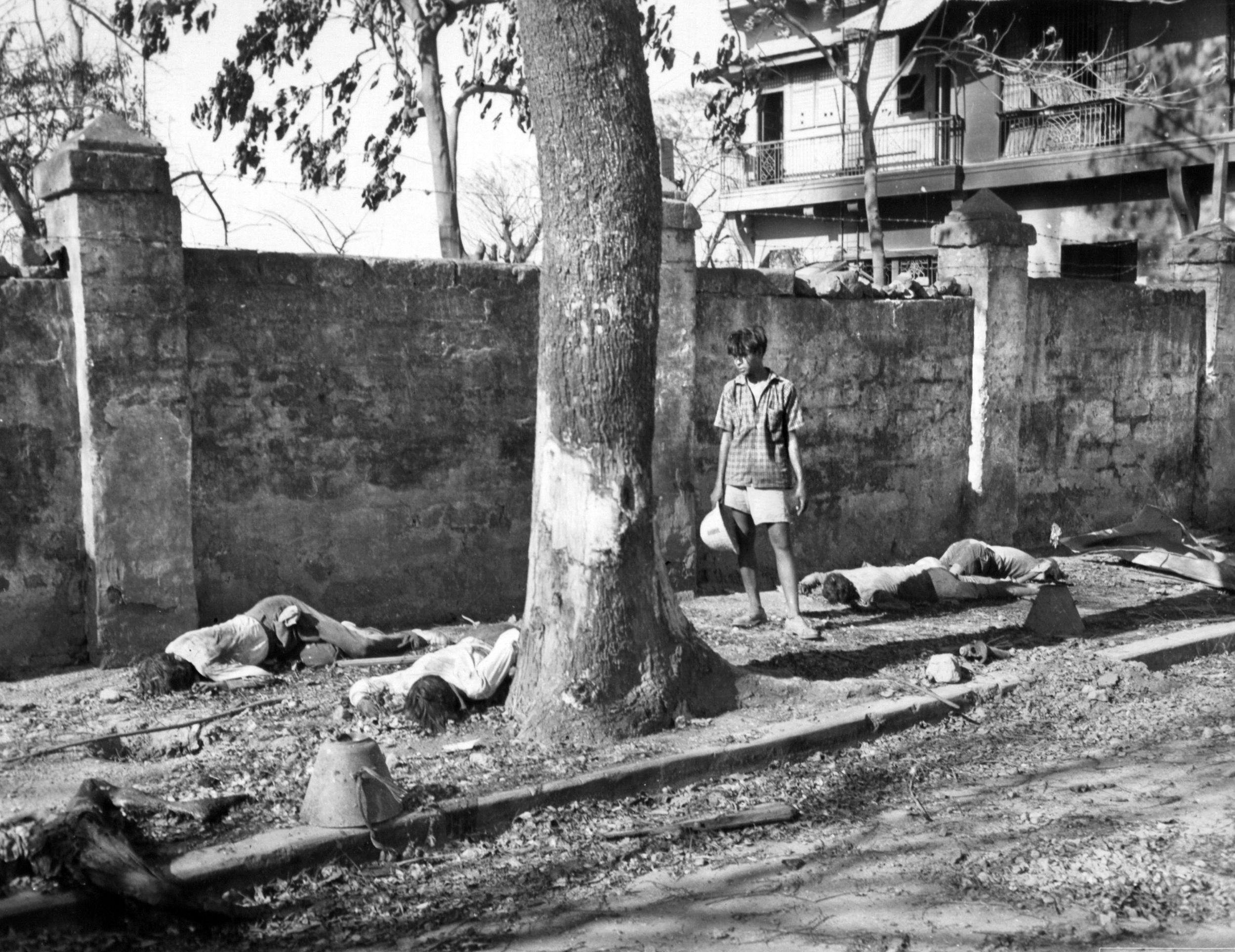

Heavy American attacks had cut Iwabuchi’s manpower to 6,000. Their command and control structure disintegrated, but they were as fanatical as ever. Knowing they would all die, they burned down buildings, raped women and girls, and slaughtered many Filipinos.

Japanese troops told Manilenos, “If you are not for us, you are against us.” The Japanese regarded even women and children as guerrillas, ordering them put to death wherever possible. In Intramuros, Japanese troops separated neutral Spanish citizens—mostly priests—from 3,000 Filipinos and gunned down the latter while imprisoning the former without food or water. Japanese troops stormed through residential areas, shooting and bayoneting refugees. The Spanish consulate in Manila, representing a neutral nation, protested to Iwabuchi. He ignored the complaint.

Instead, Iwabuchi allowed his officers to separate a large group of men and teenage boys from women and children and take them all to the Manila Hotel. There, females aged 15 to 22 were taken to surviving fancy apartment buildings where they would serve in combat bordellos for Japanese troops. One woman was raped 15 times in a day.

The Japanese showed no respect for their allies, either. The massive concrete German Club, center of that country’s expatriate community, now sheltered 1,500 refugees. Manager Martin Ohaus begged the Japanese to give his refugees safe conduct. Instead, they stormed into the club, hauled out the women, and set the building alight. When men and boys emerged from the burning building, the Japanese gunned them down. Among the dead were 18 Germans. Then, 32 German Christian Brothers were killed in the La Salle College Chapel. The body of the Vichy French consul was found with his throat cut.

At La Salle College, a Japanese battalion commander ordered the Filipinos brought together, massacred, and their bodies thrown into the river. On February 12, the Japanese battalion did just that, shooting and bayoneting refugees there. Dying Filipinos begged Father Francis Cosgrave to offer them an Act of Contrition and Absolution, and he did so. Incredibly, 10 survivors avoided further killings by hiding behind the high altar.

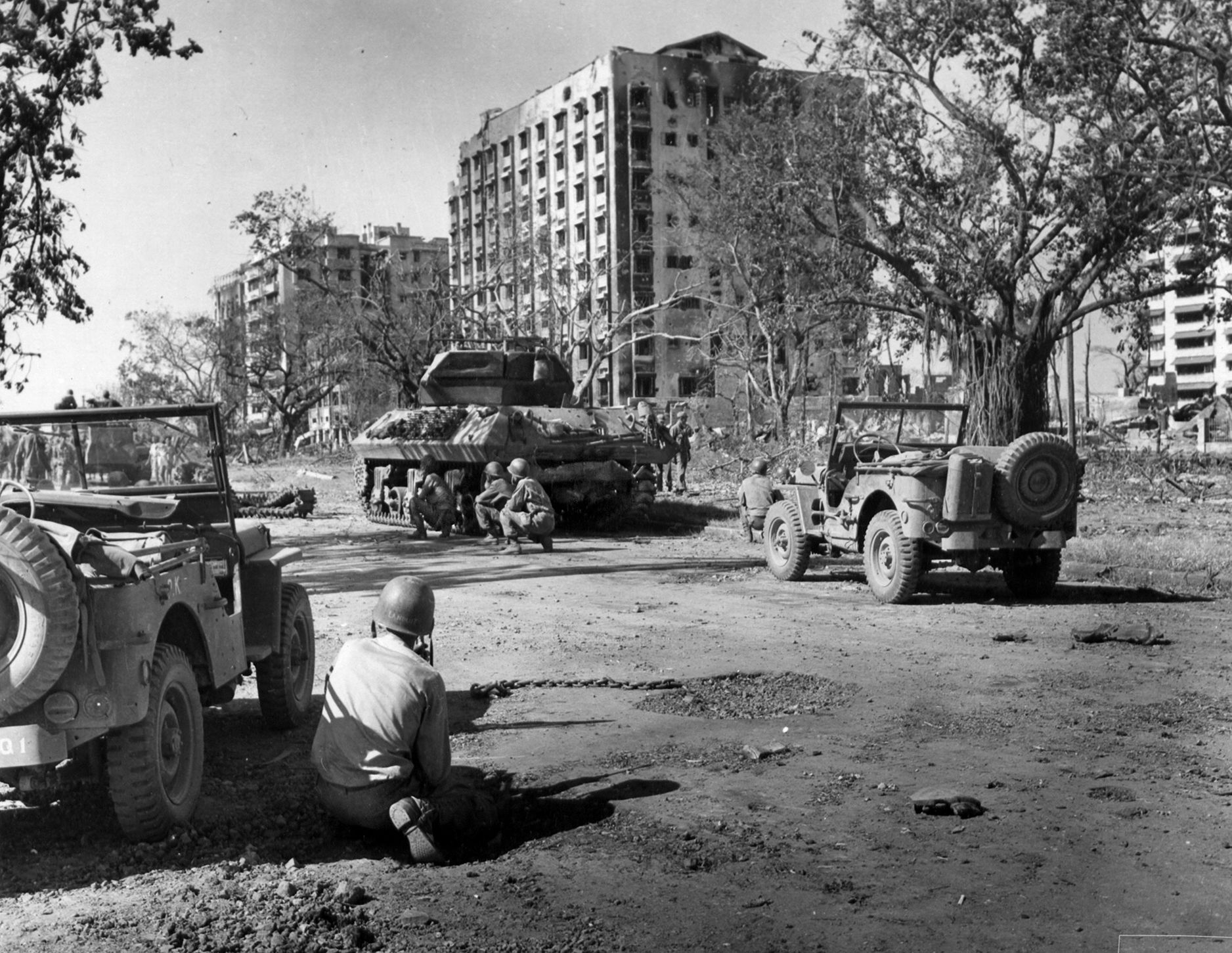

Yet, in literal terms, the U.S. cavalry was coming to the rescue. The tanks and infantry of the 1st Cavalry Division attacked into the Pasay City District, then La Salle University and the Japanese Club. Shermans blasted open Japanese bunkers. Infantrymen, however, fought street by street, house by house, and room by room. The best way to dig out the Japanese 2nd Naval Defense Battalion seemed to be to get on the roof of an enemy-held building and work downward, floor by floor, with grenades, satchel charges, and flamethrowers.

American 4.2-inch mortars could not penetrate reinforced concrete. It was ugly and bloody work, leaving behind many Japanese, American, and Filipino dead. The 3rd/148th suffered 58-percent casualties. Lacking time to bury the thousands of Filipino dead, GIs dumped quicklime on their bodies.

Worse, American fire was often indiscriminate. On February 13, U.S. artillery shelled the hospital at the University of the Philippines. However, while Japanese troops held the hospital’s administration building, they did not occupy the hospital itself, and some of the 7,000 patients and refugees perished, some from lack of food and water amid the intense heat and smoke.

The GIs slowly drove through the city toward the hospital, battling Japanese troops. As they closed in, two North American P-51 Mustang fighters swooped over the hospital and strafed it until their pilots saw civilian faces. The advancing Americans liberated the hospital on the 17th.

Griswold’s plan to liberate Manila was to cut up the Japanese defenses so that they would have to fight as isolated units. The 1st Cavalry moved south across the Pasig against limited opposition on February 10, then swung southwest to link up with the 11th Airborne. Iwabuchi was trapped—his only options were death or surrender.

Hearing this news, Yamashita ordered the Shimbu Group to counterattack the Americans from the east. Yamashita also ordered Iwabuchi to evacuate Manila when the hole was opened. On February 15, Iwabuchi retorted, “The headquarters will not move.”

Backed by airstrikes, the 112th Infantry Regiment stopped the Shimbu Group cold and forced them to retreat. Historians later argued that locking a vise around Iwabuchi was a blunder—if he had been offered a way out of the trap, he might have abandoned the city. However, retreat and withdrawal were not part of the Japanese approach to war.

Fierce fighting raged on February 12 between the 1st Cavalry and the 2nd Naval Battalion around Fort Antonio Abad, Harrison Park, and Rizal Stadium, Manila’s main baseball park. The stadium was made of concrete, 15-foot-high walls, and had four large stands, with a drainage ditch that could serve in the anti-tank role. More importantly, it was a major Japanese supply dump. The enemy set up their machine guns on the diamond. It took two days for the 1st Cavalry to clear the ballpark, inflicting 17 Japanese casualties for every American loss. After they did, long columns of Filipinos emptied the stadium of non-military supplies.

American artillery opened fire on the Remedios Hospital and only stopped when civilians ran out waving Red Cross flags, despite sniper fire, at the orbiting Piper Cub. The pilot waggled his wings, and the artillery fire stopped, saving 800 to 1,000 patients and refugees. Even so, 400 had died in the initial shellfire. Father Julio Lalor stayed in the hospital, comforting the wounded.

At Dr. Rafael Moreta’s house on Isaac Peral Street, Japanese Marines shoved about 60 refugees into the building, searched the place for valuables, shot the men, put others in the bathroom, and tossed in a hand grenade. The survivors were herded into the street, where Japanese machine guns waited. However, the Americans spotted this horror and hurled artillery fire to kill the Japanese.

Despite these atrocities, as Americans advanced through rubble they had created, the Manilenos were happy to see them. They sang “God Bless America,” and kids shouted, “Victory Joe!” as American troops handed out candy and Hershey bars.

Determination, tanks, and technology enabled the Americans to clear Dewey Boulevard and head north past the Manila Hotel to Intramuros City. Before the war, the hotel had been Manila’s equivalent of London’s Dorchester or New York’s Waldorf-Astoria, and both the Filipino and American elite had apartments there. MacArthur himself lived in the hotel’s penthouse. He was particularly determined to recover his residence, which held vast amounts of his personal belongings, including his birth certificate, father’s Bible, the library of books that belonged to him and his father, General Arthur MacArthur, who had conquered the islands in the Spanish-American War, and a pair of silver vases presented to Arthur by Emperor Meiji. MacArthur’s wife Jean had left them there, hoping that the Japanese would respect the vases and the apartment.

When the Japanese refused to yield or flee, MacArthur reluctantly authorized the 82nd Field Artillery to turn its 105mm guns on the five-story hotel. For three days, they pounded the building. The Manila Hotel withstood the bombardment, but the surrounding area was turned to rubble. The cavalrymen forced their way to the hotel, and MacArthur joined them on February 22, walking with his entourage up Dewey Boulevard, ignoring sniper fire.

“Suddenly, the penthouse burst into flame,” he wrote in his memoirs. “They had fired it. I watched, with indescribable feeling, the destruction of my fine military library, my souvenirs, and my personal belongings of a lifetime.”

The GIs stormed the hotel and captured it by nightfall. MacArthur climbed the stairs to his former penthouse. In the entrance, he found the bloodstained corpse of a Japanese colonel. MacArthur looked gloomily at the shards of his ceremonial vases. The book bindings were intact, but when he touched them, they disintegrated. A young 1st Cavalry lieutenant came up. Apparently the lieutenant thought that MacArthur had shot the colonel personally, so he grinned and said, “Nice going, Chief!”

MacArthur could only shake his head. He wrote later, “There was nothing nice about it to me. I was tasting to the last acid dregs the bitterness of a devastated and beloved city.”

Sometime later, GIs discovered in a warehouse a barrel marked “Japanese Medical Supplies.” The barrel was taken to MacArthur’s headquarters and opened. It yielded a complete silver tea service, cocktail shaker with matching cups, a silver candelabra, and silver pitcher. A furious MacArthur accused Yamashita of the larcenous act.

Now the fighting moved into the government complex and Intramuros. City Hall, the General Post Office, the Legislative Building, and the Agriculture Building were all proud replicas of similar American structures back home. The New Police Station alone was one of the toughest obstacles the 129th Infantry would face in the entire war. The Japanese held the upper floors. GIs had to fight their way up, against hand grenades dropped down staircases. The Americans brought point-blank artillery and tank fire against the concrete buildings, blasting holes in them.

Even so, the GIs were stymied. The 148th relieved the exhausted 129th and the Americans kept firing at the New Police Station until its walls started collapsing. The 145th Infantry attacked from the west side and was driven back. After eight days of brutal shellfire and close combat, the GIs took the shattered pile of debris.

The surviving Japanese didn’t wait to be killed or captured, withdrawing behind Intramuros City’s massive walls for a last stand. Griswold and Krueger again asked MacArthur to use air power against the enemy, but MacArthur refused.

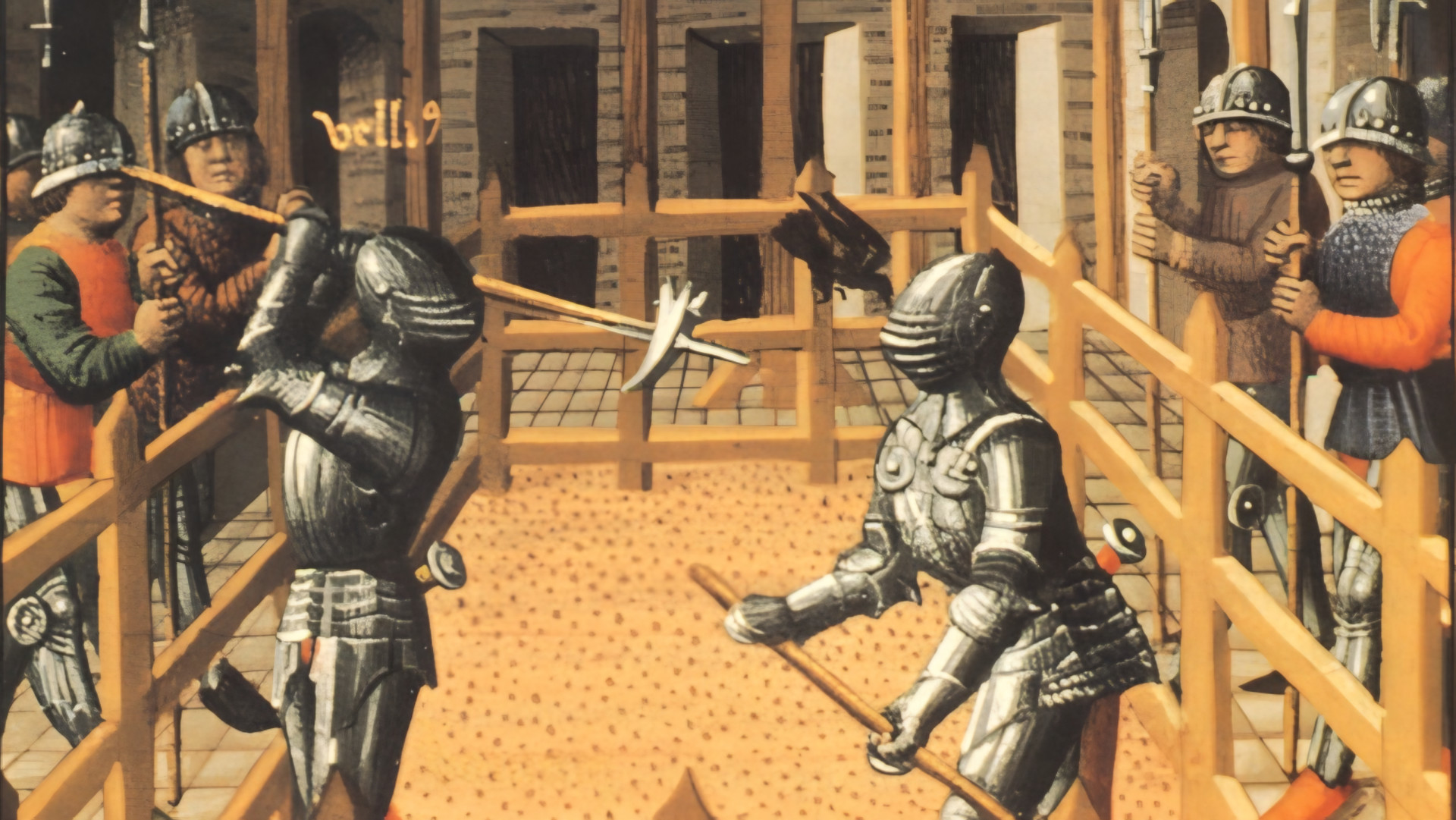

There were too many civilians trapped in the fortress, whose walls were 40 feet thick at the base and 20 feet at the top, honeycombed with internal passages. Dungeons, churches, and embrasures had been turned into strongpoints.

Griswold was enraged, noting that major cities across the world were being destroyed. “Why not here?” he wrote. “War is never pretty. I am frank to say that I would sacrifice Filipino lives under such circumstances to save the lives of my men.”

Griswold built up a huge array of M-10 tank destroyers with 3-inch guns, 105mm, 155mm, and 8-inch field artillery, anti-tank guns, and bazookas to bombard the fortress. While preparing his bombardment, Griswold pleaded with the Japanese to release the Filipinos they held hostage or prisoner. The Japanese ignored his pleas. Several Japanese troops surrendered on their own.

The American bombardment of Intramuros began on February 17, and continued until February 23, when the ground attack began promptly at 7:30 a.m. The 145th Infantry Regiment stormed past the battered Quezon Gate, fighting Japanese soldiers and sailors hand to hand. The Japanese survivors retreated into Fort Santiago, where they were finally wiped out.

The fall of Fort Santiago was critical to breaking Intramuros. Under immense American shelling, the Japanese could not hang on much longer. Iwabuchi and a collection of diehards held out in the Legislative, Agriculture, and Finance Buildings, all unintentional fortresses.

The 129th Infantry stormed across the Pasig River in assault boats, reaching the shore by 8:40 a.m. Within minutes, the 129th had connected with the 145th attacking from the east and stormed their way in. The Japanese released 5,000 hostages from the San Agustin Church and Delmonico Hotel but continued to shoot men, regarding them as guerrillas. That included imprisoned neutral Spanish and Irish priests. Iwabuchi radioed Tokyo one last time, telling the Imperial General Headquarters that his men would fight to the death.

On February 25, Iwabuchi committed seppuku, and the last Manila defenders died fighting or fled the city. The Finance Building fell on March 3, ending the battle. Weary GIs raised Old Glory over the rubble and shared their food with starving Filipinos.

There were plenty of them, but about 100,000 Manilenos had died in the fighting, mostly of them victims of ghastly atrocities. The Japanese had lost 16,665 men in the battle, virtually their entire force. The Americans took 6,575 casualties, 1,010 of them killed.

It was a terrible victory all around. Manila had been destroyed, including the great Intramuros fortress and the massive American-made buildings. The biggest victors in the struggle were likely the Allied internees and POWs, who were liberated with far less difficulty than the city itself.

The Americans put Yamashita on trial in a court-martial, charging him with the Manila horrors. He was found guilty at Bilibid Prison on December 7, 1945—Pearl Harbor Day—and hanged on February 26, 1946.

MacArthur got his big moment in Manila, even though it came after January 26. On February 27, while fighting still raged in Intramuros, MacArthur strode into the Malacanang Palace, which was intact, with Filipino President Sergio Osmena and restored the capital and political power to the Philippine Commonwealth.

MacArthur’s voice broke as he addressed the gathering. Unable to continue, he simply asked everyone present to join him in the Lord’s Prayer.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments