By Jerome Baldwin

He came highly recommended, praised by General George C. Marshall as “one of the best.” But ultimately from these high hopes and expectations would come disastrous failure. Due to the events at the Battle of Kasserine Pass, Maj. Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall would go down in history as one of the most unsuccessful American generals of World War II. Up against the German Army in North Africa, he would all but collapse. Out of humiliating defeat one of America’s most successful generals, George S. Patton, came to the fore.

After flunking out of West Point and then dropping out after a readmission, Fredendall received his commission as a second lieutenant of infantry in 1907. Among other stateside and overseas assignments, he served in the Philippines and eventually in France during World War I. He earned a reputation as an excellent trainer and administrator but did not serve in combat during the Great War.

“I Bless the Day You Urged Fredendall Upon Me”

By the time of Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa on November 8, 1942, Fredendall was a major general in command of the Central Task Force landings at Oran. In a letter to Marshall on November 12, 1942, Eisenhower stated, “I bless the day you urged Fredendall upon me and cheerfully acknowledge that my earlier doubts of him were completely unfounded.” It would prove to be an ironic statement. There were already real potential problems looming. Fredendall did not like the British or the French. Considering those were the nationalities he would be fighting alongside, it did not bode well for the campaign ahead.

It was in Tunisia that Fredendall would fail. The German and Italian troops of Panzerarmee Afrika, under General Erwin Rommel, had been routed at El Alamein in Egypt, retreating 1,400 miles westward into Tunisia by January 1943. Following the Torch landings, Hitler had ordered reinforcements sent to North Africa, and soon German and Italian troops were being ferried from Sicily into Tunisia. Notable among these was Hans-Jurgen von Armin’s Fifth Panzer Army. After suffering ignominious defeat and the retreat that followed, Rommel was eager to achieve a victory and, always looking for the enemy’s weak point, he found it—the inexperienced and untested American II Corps.

The Allies had advanced from the African coast into Tunisia, reaching the edge of the Eastern Dorsal Mountains. The British First Army under Lt. Gen. Sir Kenneth Andersen held the northern sector, with the Free French of 19th Corps D’Armee in the center, and Fredendall’s U.S. II Corps at the southern end of the line.

Early Disasters

There were signs of trouble ahead. In the early morning hours of January 30, a force of 30 panzers broke through the Faid Pass and struck the French positions there, with another force of tanks and infantry circling south and coming up behind the defenders. The French plea to the Americans for help resulted in a shambles.

A force too small for the task under U.S. Brig. Gen. Raymond McQuillin moved slowly forward before halting for the night. The next day 17 American Sherman medium tanks rolled directly into a trap and were devastated by German 88mm guns. An infantry counterattack the next day also failed, and the pass remained in German hands.

The French, suffering losses of 900 men killed or missing, were furious at the Americans. The entire ordeal revealed problems in American command and tactics, but the disastrous rude awakening that would spark the sweeping changes desperately needed was yet to come.

“Shangri-la”: Fredendall’s Leadership From the Rear

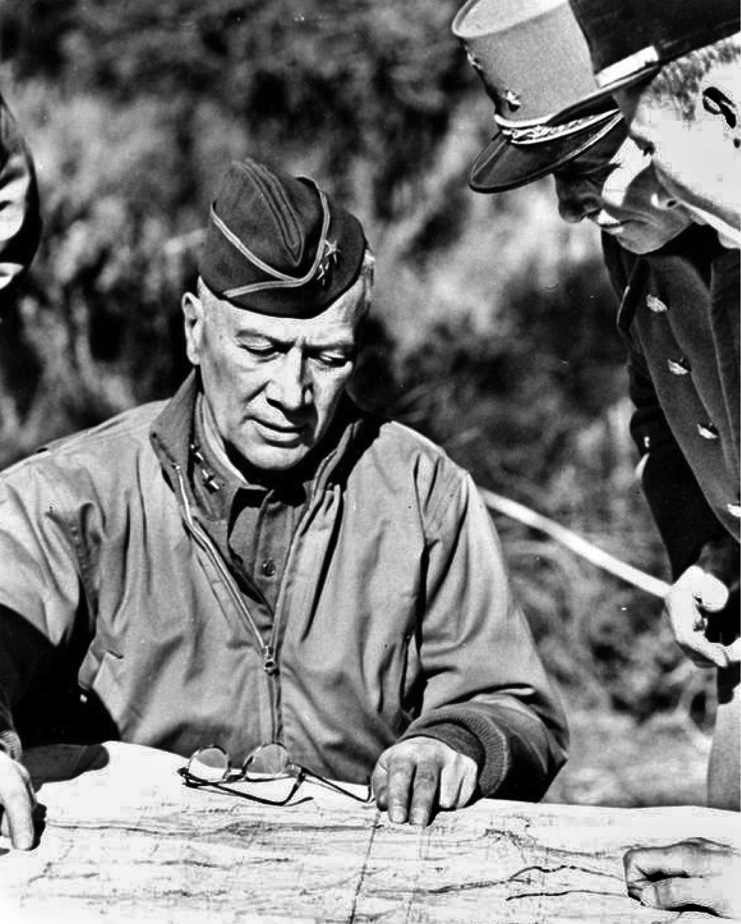

In early February, General Eisenhower managed to get away from Casablanca and visit II Corps. What he found shocked and appalled him. Fredendall had located his headquarters an incredible 70 miles behind the front line (some have said even farther back). Seemingly obsessed with an air attack, Fredendall had a battalion of engineers working to blast out underground bunkers in the side of a ravine for his staff, while having the headquarters ringed with antiaircraft guns.

“It was the only time during the war that I ever saw a higher headquarters so concerned over its own safety that it dug itself underground shelters,” Eisenhower remarked later.

At the front the situation was also alarming. Eisenhower arrived at the crossroads village of Sidi Bou Zid, where the 1st Armored Division and the 34th Infantry Division were positioned because of the enemy capture of Faid Pass on January 30. He found no defensive minefields laid down, only excuses as to why not, and assurances the job would be done tomorrow. It was an example of a troubling lackadaisical attitude among the American troops there.

Fredendall did not go up to the front line, instead relying on maps at his headquarters and issuing orders over the radio. That was undoubtedly a factor in the woeful unpreparedness at the front line in the American sector. Moreover, the fact that he was always in the rear was noted by his men, who called his headquarters “Speedy Valley,” “Lloyd’s very last resort,” and “Shangri-la, a million miles from nowhere.” Inevitably, the situation affected morale and severely eroded the confidence of Fredendall’s men in their leader.

General Lucian Truscott had this to say about Fredendall: “Small in stature, loud and rough in speech, he was outspoken in his opinions and critical of superiors and subordinates alike. He was inclined to jump to conclusions which were not always well founded. Fredendall rarely left his command post for personal visits and reconnaissance, yet he was impatient with the recommendations of subordinates more familiar with the terrain and other conditions than he.” Fredendall routinely ignored intelligence reports, bypassed subordinate commanders, and micromanaged troop dispositions down to company level.

He often used blowhard, tough-guy sounding language in an attempt to cover up his inability and indecisiveness. Phrases such as “Go smash ‘em,” “Pull a Stonewall Jackson,” “Go get ‘em at once,” or “Use your tanks and shove” were common.

He also issued orders using wording that no one understood. His intention was to confuse the enemy if he was listening in, but orders such as “Move your command, i.e., the walking boys, pop guns, Baker’s outfit and the outfit which is the reverse of Baker’s outfit and the big fellows to M, which is due north of where you are now, as soon as possible. Have your boys report to the French gentleman whose name begins with J at a place which begins with D which is five grid squares to the left of M,” only managed to baffle his own people.

The Thin American Line

When Ike visited the II Corps units near Sidi Bou Zid on the night of February 13, he had no idea that within hours the Germans would launch an offensive under Rommel and von Armin that would unleash a disaster for the Americans. Fredendall, against the advice of his 1st Armored Division commander, Maj. Gen. Orlando Ward (whom Fredendall disliked and so deliberately ignored) and others, had kept American forces spread thinly along the front instead of maintaining a strong mobile force to counter any German attack—wherever it might happen—or take swift advantage of an opportunity. Time had run out to organize such a mobile force. The next day, February 14, the Germans attacked, and all hell broke loose.

Things rapidly fell apart for the Americans. Everything seemed to go wrong. The lack of discipline under Fredendall’s command came to a head with the German onslaught, and Fredendall’s actions in the battle speak for themselves.

At his headquarters, well back from the fighting, Fredendall was unable to control the situation. From Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksaira, two hilltop defensive positions Fredendall had ordered set up which flanked Sid Bou Zid and were too far away from each other to offer any mutual support, American soldiers could only watch helplessly as the Germans rolled over their comrades below while panic spread rapidly amid the savage mauling. An understrength counterattack by the Americans on February 15 failed, Sidi Bou Zid had to be abandoned, and the Americans on Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksiara were cut off.

By the time Fredendall issued orders for the hilltop defenders to break out it was too late. Although they tried to make it back to Allied lines, only 300 of the original 900 men made it. One of those taken prisoner was Lt. Col. John Waters, General Patton’s son-in-law.

The attack quickly turned into a rout. Panicked American troops, only wanting to escape the maelstrom, fled in chaotic pandemonium rearward under terrifying attacks by Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive bombers. Forced back 50 miles, disorganized and demoralized by the stinging defeat, the Americans fell back to the Kassarine Pass, which pierced the Western Dorsal Mountains and provided a gateway for the Germans to slice into the Allied rear areas.

The German Breakthrough at the Battle of Kasserine Pass

With the situation extremely desperate, Eisenhower sent 2nd Armored Division commander Maj. Gen. Ernest Harmon out to Fredendall. He was identified as a “useful senior assistant” sent to help Fredendall in “the unusual conditions of the present battle,” although in reality he was there to assess the situation at II Corps for Eisenhower. Arriving at 3 am, Harmon found Fredendall groggy from lack of sleep. Obviously broken by circumstances and a defeated man, Fredendall simply said, “The party is yours,” and went to bed. Taking control, Harmon managed to stabilize things. Harmon reported back to Eisenhower that Fredendall was “no damn good.”

After more heavy fighting, the Germans did manage to get through Kasserine Pass. The arrival of Allied reinforcements combined with the Germans’ own command problems to grind the offensive to a halt. In just 10 days the Americans had lost 183 tanks and 7,000 men, including 300 killed and 3,000 missing.

Time was running out for Fredendall. In early March, Eisenhower pulled General Omar Bradley aside at Tebessa. Bradley had recently finished an inspection of II Corps, and Ike asked him about the situation there. “It’s pretty bad,” replied Bradley. “I’ve talked to all the division commanders. To a man they’ve lost confidence in Fredendall as the corps commander.”

Patton Takes Command of II Corps

On March 4, Patton was given command of II Corps, writing in his diary, “Well it is taking over rather a mess but I will make a go of it.”

Patton reached II Corps headquarters on March 6, finding Fredendall at breakfast. Initially, his impression of Fredendall personally was positive, but when he discovered how bad things were with the lack of discipline, no saluting, and the slovenly appearance of so many officers and men, he wrote in his diary on March 13, “I cannot see what Fredendall did to justify his existence. Have never seen such little order or discipline.”

Under the leadership of “Blood and Guts” Patton, however, duty in II Corps was transformed. Rigorous training regimens were imposed; all officers were required to wear neckties and helmets. Decades later, one of the officers who was there when Patton took over remembered his initial encounter with the legendary general: “General Patton said, ‘Every man old enough will shave every day. Officers will wear ties in combat.’ And then he came up to about a foot in front of my face and said, ‘And anyone wearing a wool-knit cap without a steel helmet will be shot!’”

Bradley, now Patton’s deputy commander, observed, “Each time a soldier knotted his necktie, threaded his leggings, and buckled on his heavy steel helmet, he was forcibly reminded … that the pre-Kasserine days had ended, and that a tough new era had begun.”

It was the start of a turnaround that resulted in victory at El Guettar in the eight-day Allied offensive that began just 10 days after Patton took command. The Americans had learned a hard lesson well, and the painful but eye-opening experience of February 1943 ultimately paid off for them for the rest of the war.

For Lloyd Fredendall, however, the fighting was over. He was sent back to the States, where he remained for the duration, training men. He retired in 1946 and passed away in 1962, at the age of 79.

Blame For the Catastrophe at Kasserine Pass

The fighting in February 1943 became known as the Battle of Kasserine Pass, a humiliating experience for the Americans although it must be remembered that many U.S. soldiers fought bravely and tenaciously in the chaos and confusion.

Not all of the blame for the disaster of Kasserine can be laid on Fredendall’s shoulders; there were other factors behind what happened. One was the reality that the American soldiers at that point were inexperienced—something beyond anyone’s control. There was also a widespread overconfidence among them. Anything Fredendall or anyone else could have done to alter their unrealistic mind-set that a quick and easy victory lay ahead likely would not have had much effect.

Still, Fredendall was largely culpable in what happened. He violated command structure and kept commanders in the dark by withholding vital information, bypassing them, and causing confusion. He was more interested in his own safety than in being constantly aware of what was happening at the front.

The fact that he issued orders worded in incomprehensible nonsense was bizarre without question. How could a U.S. Army general act in such a way? He isolated himself from his men and was responsible for an appalling lack of discipline.

Fredendall sounded like a fighting general, and with his exemplary service record prior to World War II he seemed a likely success. But battle makes short work of hype or false bravado, and it made short work of Lloyd Fredendall.

Author Jerome M. Baldwin is a resident of Amherstburg, Ontario, Canada. He is a veteran of the Canadian Army, having served as a fire control systems technician.

May I ask why Maj. Gen. Fredendall was subsequently promoted to Lt. General, after being fired and disgraced for his failure as a leader and getting large numbers of American soldiers killed due to his leadership and combat management inadequacies? Thank you.

He was fired and promoted at the same time

…sounds like a modern CEO

Sounds like they sent a Millenial to do a Boomer’s job!!!

His Wikipedia bio says since Ike never formally reprimanded him, Fredendall was eligible for the third star, which he duly received. Just amazing.