With the 2003 United States invasion of Iraq still overshadowing all aspects of American life, it is too early to predict what historians will say definitively about the enterprise. But as this issue of Military Heritage demonstrates, all leaders—from George W. Bush on—would do well to heed the warning of another president, one with far more military experience than the current resident of the White House. “Every war,” said Dwight D. Eisenhower, “will astonish you.”

The wisdom of that hard-earned remark is underscored by the varying fates of three invasions highlighted in this month’s issue. For the Athenian general Nicias, the 415 bc invasion of Syracuse confirmed his own worst fears about undertaking a voluntary invasion of a city-state that had not directly attacked him. Two years of brutal siege warfare followed, giving the lie to hotheads such as the traitorous Alcibiades, who had predicted that the invasion would be both easy and glorious. Nicias and his army eventually paid dearly for Alcibiades’s foolhardy bravado.

Prussian monarch Frederick II anticipated a similarly easy task when he sent his forces marching into neighboring Silesia, Austria, in December 1740. Only after he had been driven from the battlefield at Mollwitz in fear for his life, and a more cool-headed commander, Field Marshal Count Kurt von Schwerin, had managed to rally the Prussian forces, did Frederick realize the true gravity of his undertaking. Unlike Nicias, Frederick ultimately would succeed in his invasion, but at the cost of provoking a much wider war in central Europe. Never again would he underestimate his opponents. “Mollwitz,” he said, “was my school.”

In 1980, Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein observed the unsettled conditions inside revolution-torn Iran and determined that the time was ripe to launch a massive and unprovoked invasion of Iraq’s traditional enemy. Eight years and three million casualties later, Hussein was still in power in Baghdad, but his invasion had failed to gain an inch of Iranian territory. Proving that he was incapable of learning from his own history, Hussein would invade another of his neighbors, Kuwait, 10 years later—a move that would lead indirectly to his own eventual death by hanging after American forces invaded his own country for reasons that are still being debated as we write.

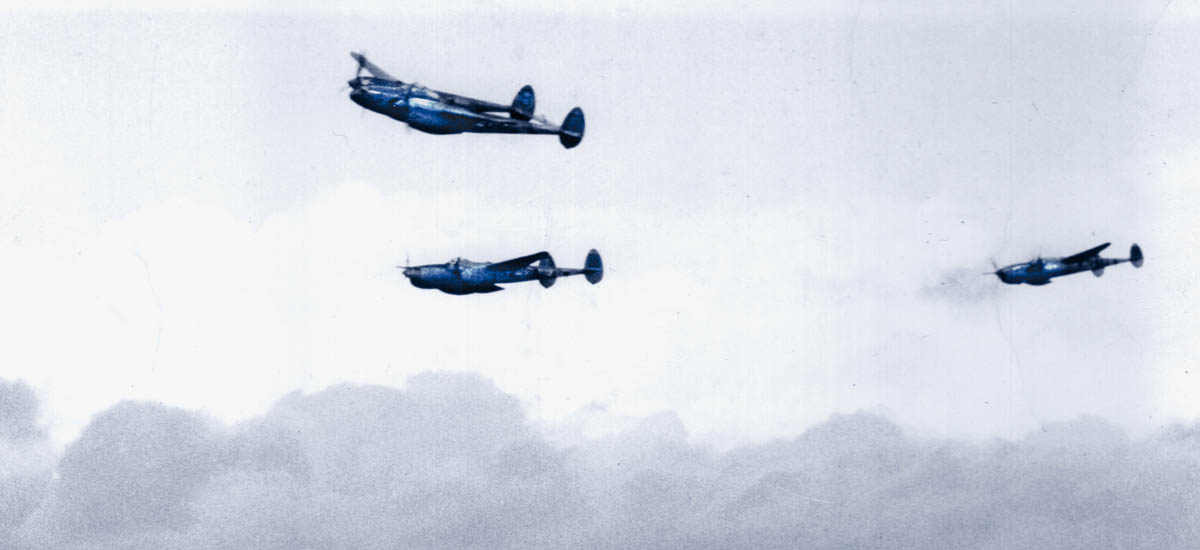

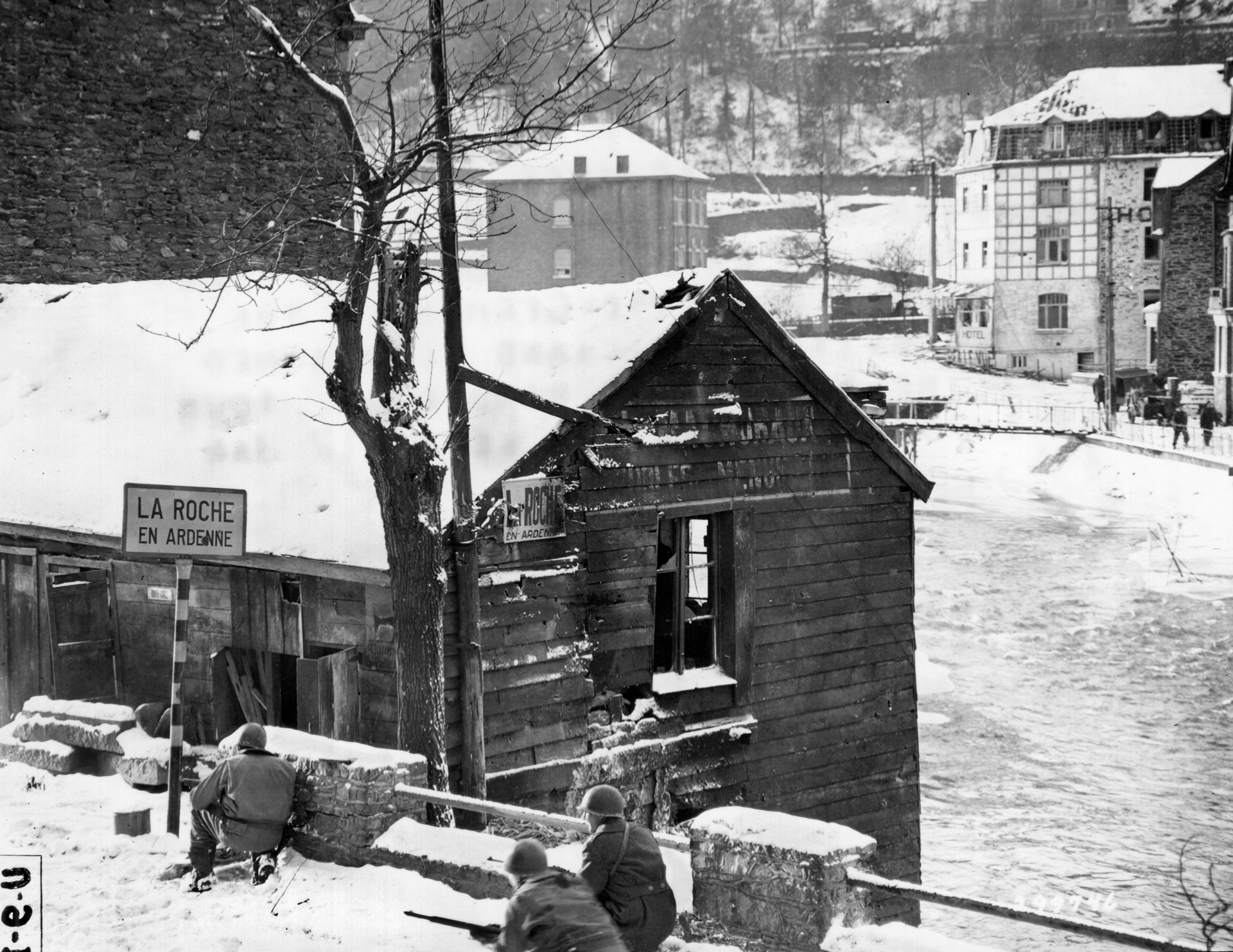

Dwight Eisenhower, who led the largest and arguably the most successful invasion in military history—the D-Day landings and the subsequent Allied drive across western Europe to Nazi Germany—could speak with vast personal experience about the subject of war. A graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point, Eisenhower knew his history. He was under no illusions about the hidden difficulties facing any invasion. Famously, he wrote out two messages on the eve of D-Day, one announcing its success, the other taking personal responsibility for its failure. To his own relief and the world’s great benefit, he and his forces did not fail.

Even in victory, however, Eisenhower had little use for war as an instrument of clever policy-making. “When people speak to you about a preventive war,” he said, “you tell them to go and fight it. After my experience, I have come to hate war. War settles nothing.” The key word there is “experience.”

Roy Morris Jr.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments