By Herb Kugel

In September 1943, Canada’s top air ace, the “Falcon of Malta,” Flying Officer George Beurling, was faced with two problems. He disliked his new cap and he disliked his wing commander. The first problem was easily solved. Beurling, unhappy with the cap because he felt it made him look like a rookie, pitched it into the air and put a blast from his shotgun through it. He felt this made the cap suitable.

Luckily, Beurling failed in his attempt to solve his second problem. Beurling was serving with 403 Wolf Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), based at Headcorn, Kent, England. He saw his wing commander flying overhead in a De Havilland Tiger Moth and blasted away at the plane with his shotgun. While the wing commander was unhurt and never knew what happened, his ground crew was baffled by the small holes that had appeared in the bottom of the plane’s left wing. Only George J. Demare, one of Beurling’s ground crew, knew of the shotgun blasts; he did not report Beurling. Demare’s loyalty was understandable. If Beurling disliked officers, he liked and was generally liked in return by his ground crew.

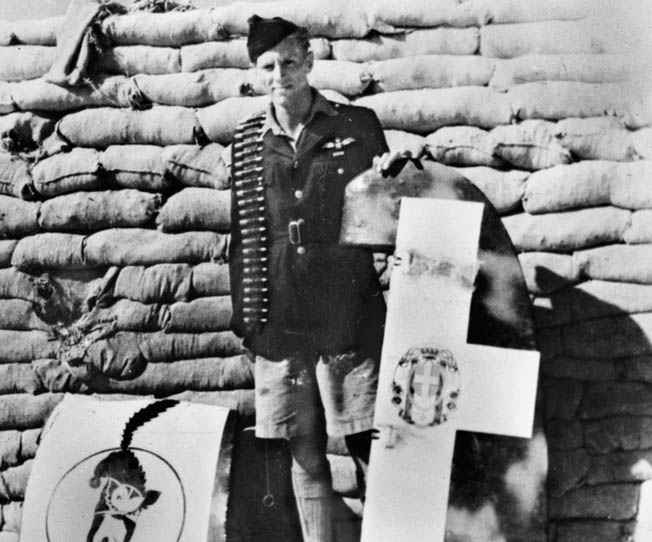

Beurling’s behavior was not altogether unexpected. Air historian Dan McCaffery wrote of him: “They called him ‘Screwball,’ ‘Buzz’ and the ‘Falcon of Malta’ [and] he was the greatest Allied fighter pilot of the Second World War. [He] was a complex, even paradoxical individual…. He craved fame but cared nothing for promotions. He loved attention but had little use for intimacy. And when he died, he was remembered as Canada’s most successful and tragic combat hero of World War II.”

Beurling was a loner, a difficult man who twice rejected an officer’s commission. There was something shadowy and forbidding in him. It showed in his eyes.

Destined for the “Free Sky”

George Beurling was born on December 6, 1921, in Verdun, Quebec. He grew up in the Plymouth Brethren, an extremely conservative religious group that had absolute and literal faith in the Bible. Daily Bible reading was mandatory; alcohol, tobacco, and virtually all pleasures were forbidden. Even owning a radio was initially rejected. Because of this background, Beurling never swore, drank, or smoked. Although he was athletic and became a good swimmer, he never participated in team sports. While he was a loner from early childhood, he did have one constant passion. He wanted to fly.

“Ever since I can remember,” he recalled, “airplanes and to get up in them into the free sky had been the beginning and end of my thoughts and ambitions.”

The “free sky” was everything to Beurling. He had few friends; his school grades were mediocre. The only books that interested him were about aviation, especially about World War I combat flying. He repeatedly studied the air battles and tactics reported in these books. He regularly skipped school and spent every moment he could at the local airport. Just before his 11th birthday, on his way to the airport, he was caught in a violent rainstorm and given shelter in a hangar. A kindly pilot, feeling sorry for the drenched little boy, offered to take him up for a spin if he obtained parental permission. Beurling’s mother, thinking it was a joke, agreed, but it was no joke to her son. He flew and was hooked for life.

Beurling was treated coldly by his parents. He was strapped and banished to his room for playing hooky from school and going to the airport. He did not mind the banishment. He spent hours, always alone in his room, carefully building model airplanes. He sold the models and used the money he made from their sale and doing odd jobs or selling newspapers on street corners to pay for weekly flying lessons, which cost $10 per hour. He was 12 when he first took the controls of an airplane in 1933, and then soloed in the midwinter of 1938, probably just after he turned 17. He passed all the examinations for a commercial pilot’s license but was refused the credential because he was too young.

The refusal did not stop him. He dropped out of high school, jumped onto a railroad boxcar, and rode the rails to Gravenhurst, Ontario, where he managed to get a job carrying air freight into the bush for mining companies. He worked as the navigating co-pilot, something he could evidently do without a pilot’s license. The work was dull, but he picked up a great deal of air experience. Because of this, he was soon able to obtain his pilot’s license.

Beurling then headed west to Vancouver, British Columbia, where he hoped to obtain a commercial license and then join the Chinese Nationalist Air Force in its battle against the Japanese invasion of China. Wanting to fight in the air was his only passion; it remained so for the rest of his life. He entered a flying competition in Edmonton, Alberta, that included several RCAF pilots. Beurling won the event and, as he accepted his trophy, he told a stunned crowd that Canada was in serious trouble if the RCAF pilots in the competition were its best. He believed these words came back to haunt him.

Beurling attempted to go to San Francisco from British Columbia. He thought that once in San Francisco, he could somehow get to China. He attempted to sneak into the United States as a stowaway on a tramp steamer but was caught and arrested as an illegal immigrant. He spent two months in a U.S. jail and was then dumped at the Canadian border. Back in Canada, he drifted aimlessly eastward.

Accepted by the RAF

When World War II began on September 1, 1939, Beurling suddenly found a new purpose. He was three months short of his 18th birthday. He immediately tried to enlist in the RCAF but was rejected because of his mediocre school record. Bitterly disappointed, he felt the real reason for his rejection was speaking out at the air show in Edmonton. He resented the RCAF for the rest of his life because of this rejection.

Beurling became even more compulsive in his obsession to fly in combat. He wanted to go to Finland and join the Finnish Air Force in its fight against the Russian invasion but was blocked when the Finnish Embassy insisted that, because of his age, he must obtain written permission from his parents. His parents refused.

Beurling then signed on to a munitions freighter and sailed for England. He was determined to jump ship and join the RAF, but in England the recruiting officers informed him that they needed to see his birth certificate. Unfazed, Beurling returned to his ship and sailed back to Canada for his birth certificate, which he brought back to England. While many of the ships around Beurling were attacked by German submarines, he was unhurt.

He was overjoyed when the RAF accepted him. However, he began his training by buzzing a control tower and knocking a sentry over a railing with the force of his plane’s prop wash. Repeated wild flying such as this earned him the nickname “Buzz.” In spite of his bizarre behavior, Beurling performed brilliantly in training and was offered a commission. He turned it down. He said he distrusted officers and wanted to live and work with the sergeant pilots.

Flying “Tail End Charlie”

After completing his training, Beurling was posted to 403 Squadron, where he was again offered a promotion, which he again rejected. His squadron commander thought little of him and gave him a “Tail End Charlie” flight position. This meant that Beurling would bring up the rear, and since the German pilots generally attacked from the rear, Tail End Charlie was usually the first plane to be hit. During this period, the RAF was using flights of four aircraft, three flying in a V, while a fourth plane, Tail End Charlie, flew slightly above and behind the others, theoretically weaving back and forth in the V while looking for Germans. It was an impossible formation and cost the lives of many pilots before the RAF abandoned it.

On March 23, 1942, when the squadron was participating in a sweep over northern France, Beurling, despite his fighter inexperience but with wonderful eyesight, was the first to observe some German Focke Wulf FW-190 fighters diving out of the sun on his squadron. Beurling radioed “Bandits!” but was ordered to maintain radio silence, and moments later he had three 190s on his tail. Tracer bullets were striking inches from his cockpit. His engine hood was shot away.

“I was dead meat until I suddenly got a brainstorm,” he later recalled.

He dropped his Spitfire’s landing gear and wing flaps. The plane slowed, and the three German fighters overshot him. Beurling managed to get his plane back to England where he raged at his flight commander, furiously denigrating him in front of the entire squadron. While Beurling was justified in attacking his commander’s stupidity, doing so in no way aided him. Shortly after this, he was transferred to 41 Squadron. There is a certain irony in Beurling’s transfer, as 403 Squadron was being transformed into an all-Canadian unit. Beurling, being a member of the RAF, would therefore have been transferred to another RAF squadron anyway.

In 41 Squadron, Beurling was again forced to fly the hated Tail End Charlie position. In spite of this, he managed his first kill. He was flying 24,000 feet above Calais when his flight was attacked by five FW-190s. Once again, his tail-end position Spitfire took the brunt of the attack. German cannon shells slammed into both wings, knocking out his two cannon but leaving his four Browning machine guns intact.

Again, Beurling’s flying skill saved his life. He zoomed straight up into the sun. The Germans followed him and, losing sight of him in the blinding yellow glare, they streaked past him. As they roared by, Beurling fired his machine guns at the middle FW-190. The blast ripped both wings away from the fuselage, which split in two. Beurling, believing the German pilot died instantly, expected to be congratulated when he landed. Instead, he was given a tongue lashing for breaking formation.

Beurling, in a rage, snapped back defiantly. “Six of us broke formation,” he retorted. “Five Jerries and I [sic].”

Two days later, Beurling was again flying Tail End Charlie over Calais. Once more, thanks to his incredible vision, he spotted attacking German fighters before anyone else did. He radioed a warning and was again ignored, but this time he did not care. He left formation without permission, attacked the incoming German planes, shot down their leader, and received yet another reprimand for disobeying orders. Beurling had been correct on each of his three missions; his officers were wrong. Whatever their other reasons for disliking him, it appeared they were jealous of his flying skills, amazing vision, and extraordinary shooting ability.

A Self-Taught Shot

No matter what the reasons for their dislike, Beurling had had enough. Disgusted with the stupidity of his commanding officers, he offered to take the place of a married pilot who did not want to be sent to Malta. Beurling’s request was promptly accepted.

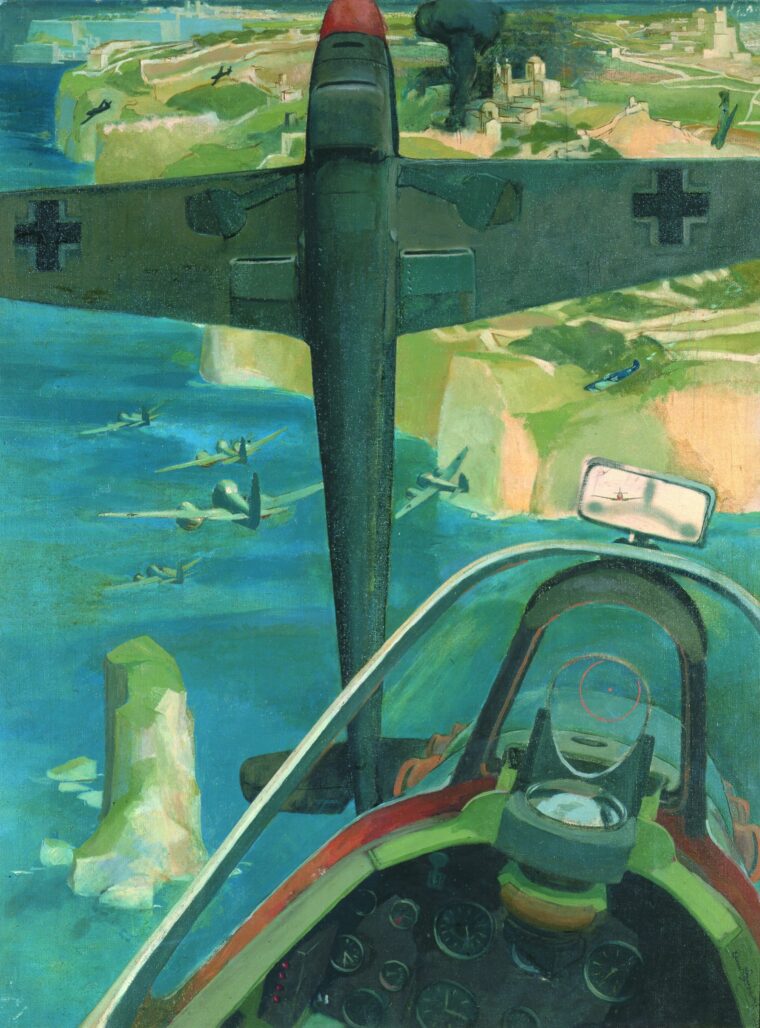

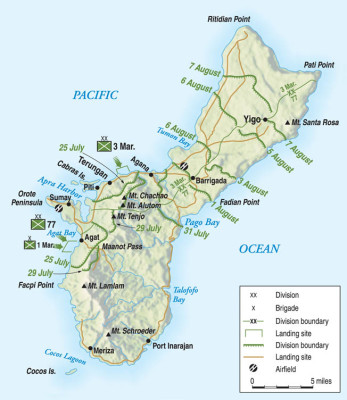

On June 9, 1942, George Beurling was not yet 21 when he flew a Spitfire V from the deck of the aircraft carrier HMS Eagle to Malta and landed at Takali Airport. He came down in the middle of a raid on the airfield. Beurling was instantly part of a desperate British defense against a vastly superior armada of German and Italian airplanes, which sometimes outnumbered the British 10 to 1.

Malta had been under Axis siege since June 11, 1940, the day after Italy declared war on Great Britain. On that day, the island endured eight separate air attacks by the Regia Aeronautica, the Italian air force, and that was just the beginning. Malta was critically important; it is crucially located in the Mediterranean, 180 miles from the North African coast. Thus, it was an ideal location for launching sea and air strikes against Axis ships carrying supplies to the Italian and German forces in North Africa. Sicily is only 70 miles from Malta, and extensive German and Italian airpower was based there.

Beurling was posted to 249 Squadron, where his reputation as a troublemaker preceded him. However, few expected what happened. Laddie Lucas, his wing commander, writing four decades later, reported, “Beurling was untidy, with a shock of fair, tousled hair above penetrating blue eyes. He was high strung, brash and outspoken.… I suspected that his rebelliousness came from some mistaken feeling of inferiority. I judged that what Beurling needed … was not to be smacked down but to be encouraged. His ego mattered very much to him, and from what he told me of his treatment in England, a deliberate attempt had been made to assassinate it. I [promised] that I would give him my trust and that if he abused it he would be on the next aircraft out of Malta. When I said all this those startling blue eyes peered incredulously at me as if to say that, after all his past experience of human relations, he didn’t believe it. He was soon to find out that a basis for confidence and mutual trust did exist. He never once let me down.”

Beurling never once let Lucas down during his time at Malta. He became a Canadian national hero through his amazing shooting. On June 12, he shot down his first Messerschmitt Me-109 fighter by blowing its tail surfaces away with a single burst of his guns. Since nobody saw the plane crash, Beurling was credited with only damaging it, although it is impossible to imagine the plane flying home without its rudder.

A lull followed, but while other RAF pilots relaxed, Beurling spent countless hours working out the principles of deflection shooting, that is, how far ahead of the enemy he had to shoot for the targeted plane to fly into his bullets. Beurling struggled with this and mastered the technique, but one of his learning tactics was not pleasant for Malta’s lizards. He often stood motionless with his .38 pistol, waiting for a lizard to approach and fill his field of vision at about the size of a German fighter at 250 yards. Often enough, he hit the lizard with one bullet.

Beurling’s self-training worked. On July 6, flying three sorties, he was credited with three confirmed kills: two Italian Macchi 202 fighters and an Me-109. When these kills were added to his two victories before coming to Malta, Beurling became an ace but there was no celebration party. His fellow pilots snubbed him as a loner. Beurling, if he celebrated at all, celebrated alone.

“Screwball” George Beurling Earns His Fame (and His Name)

Beurling’s marksmanship was becoming legendary. On July 27, he shot down the Italian ace Furio Doglo Nicolt and his wingman. On July 29, he shot down another Me-109. By the end of July, he was credited with 17 confirmed kills, 15 of them during his “July Blitz,” the period from July 6 through July 29. He was awarded a Distinguished Flying Medal (DFM) for eight victories and a bar at the end of the month for his 17 victories. He was becoming famous.

The air battles over Malta were attracting worldwide attention. Reporters demanded to know more about England’s top ace, George Beurling, “The Falcon of Malta,” as the press called him. The RAF responded to Beurling’s growing fame by ordering him promoted, something he still did not want. He was made a Flying Officer (F/O) on July 30. The reason the RAF forced a promotion on Beurling was embarrassment. It would look terrible for the RAF if it became known that their “Falcon” refused to be an officer. Nevertheless, Beurling ignored his promotion and continued to live and eat with the sergeant pilots.

It was about this time that Beurling received the nickname “Screwball,” earning it through behavior that might be labeled “psychotic” by modern standards.

In his book Malta, Laddie Lucas recalled, “He possessed a penchant for calling everything and everyone—the Maltese, the Bf-109s, the flies—those goddam screwballs…. His desire to exterminate was first made manifest in a curious way. One morning, we were on readiness at Takali, sitting in our dispersal hut in the southeast corner of the airfield. The remains of a slice of bully-beef which had been left over from breakfast lay on the floor. Flies by the dozen were settling on it…. Beurling pulled up a chair. He sat there, bent over this moving mass of activity, his eyes riveted on it, preparing for the kill. Every few minutes he would slowly lift his foot, taking particular care not to frighten the multitude, pause and—thump! Down would go his flying boot to crush another hundred or so flies to death. Those bright eyes sparkled with delight at the extent of the destruction. Each time he stamped his foot to swell the total destroyed, a satisfied transatlantic voice would be heard to mutter “the goddam screwballs!”

George Beurling’s Revenge

As the air war over Malta continued through the summer and into autumn, the fighting became more brutal. Atrocities were committed by both sides. Although Beurling always carried a Bible with him when he went into the air, he nevertheless shot and killed Axis pilots who were bailing out or were parachuting from their burning planes. He justified this brutal behavior by telling a reporter, “The way I figure it, he might get down, get back to Germany, and come back to shoot me down.”

Beurling also pointed out that his shootings were an act of revenge. A Spitfire pilot had been shot dead while parachuting down. The stress on everyone grew worse, but Beurling just wanted was to keep flying and fighting. Lucas wrote, “He [was] … exhausted by the physical demands of fighter combat, stress, heat, poor nutrition and a form of dysentery they called “the Dog.” [He] had lost 50 lbs since arriving in Malta…. He was bed ridden for a week, but managed to drag himself into the air to battle the Messerschmitts that circled Malta. Several flights of Bf-109s jumped him. He managed a short burst that brought down a German, but his comrades shot Beurling’s plane to pieces. He crash landed in a field because his parachute was too loose for him to jump out. By the end of August he collected a shared victory over a Junkers Ju-88 that had been separated from its fighter escort.

Last Flight Over Malta

Beurling was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) in September. His “October Blitz” gave him eight victories in five days. On October 10, Beurling flew his last mission over Malta. It was spectacular. He led three Spitfires in an attack on eight Junkers Ju-88 bombers protected by 50 fighters. He shot one bomber, but seconds before it crashed into the Mediterranean, bullets from its tail gun struck him in a finger and forearm. Beurling, ignoring the blood pouring from his wounds, went on to attack and damage a Messerschmitt Me-109, but two Messerschmitts had closed behind him. The cannon fire from one shredded his Spitfire’s tail and wings. Bullets from the second Messerschmitt shattered the canopy of his cockpit. He dove for the water, plunging at 600 miles per hour, and managed to lose the two German fighters. As he pulled out of the dive, he spotted a Messerschmitt and shot it down, but doing this attracted more German planes.

Beurling later related what happened: “A Messerschmitt nailed me from behind…. A chunk of shell smashed into my right heel. Another went between my left arm and body, nicking me in the elbow and ribs. Shrapnel spattered into my left leg. The controls were blasted. The throttle was jammed wide open and there I was in a full-power spin, on my way down from around 18,000 feet. I threw the hood away and tried to get out, but the spin was forcing me back into the seat. ‘That is it,’ I said to myself. ‘This is what it’s like when you’re going to die.’ I didn’t panic. If anything, I was resigned to it. What the hell, this was the way I’d always wanted to go. Then I snapped out of it and began to struggle again.

“The engine was streaming flame but I managed to wriggle out of the cockpit and onto the port wing from which I could bail into the inside of the spin. I was down to 2,000 feet. At about 1,000 I managed to slip off. Before I dared pull the ripcord I must have been around 500. The chute opened with a crack like a cannon shell and I found myself floating gently down, the damnedest experience in contrasts I’ll ever have.

“I caught my breath, pulled off a glove and dropped it to get some idea of the distance between me and the sea. A breeze caught it and the glove went up past my face. I laughed like a fool, then tugged off my flying boots and dropped them. Just as I did I hit the water.”

Beurling was rescued by a shore launch. When the rescuers reached him, he was floating in blood-stained water, mumbling about the Bible his mother had given him. The rescuers, searching his pockets, found the Bible. The words of L.G. Head, one of Beurling’s rescuers, report what was going through Beurling’s mind: “He told us he would not fly without his Bible…. Before we got ashore, he was most adamant that he was going to fly and fight within a few hours.…”

Evacuated With 28 Victories Over Malta

No matter how much he wanted it, Beurling was too badly injured for a quick return to combat. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his 28 victories over Malta and was patched up as well as possible and then readied for evacuation to Gibraltar. He did not want to go. Nevertheless, at about 2:30 am on November 1, 1942, Beurling was one of many pilots and civilians who boarded a standard four-engine Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber. The Liberator was without passenger seats, but virtually no one seemed to mind because it was flying to Gibraltar and then on to England. Everyone else was looking forward to getting out of Malta, but Beurling was miserable.

While Beurling lived for air combat, he also seemed to have a sixth sense. Perhaps he was aware that what he felt was his shining psychological moment coming to an end. He began talking about going to China when World War II ended because he felt there might be a war there.

Beurling called Malta “the fighter pilot’s paradise.”

To make things worse, the Liberator on which Beurling was flying crashed while landing in Gibraltar. There were many casualties, but Beurling survived. Despite being weighed down by a heavy plaster cast on his foot, he managed to swim 160 yards to shore. While Beurling’s stay in a Gibraltar hospital was short, it seemed to make him reflective.

“I lay abed that night and looked out the window on the lights of Gibraltar,” he wrote. “So this was how it had to end. You fly and fight and live for the minute, and you team up with guys who know nothing about you and about whom you know nothing. All you know is the other guy is full of guts and does the job. Then the break comes and you all fly away together, each to go his own way at the journey’s end, but each with something to share with the others that none of you will ever forget….”

Beurling was a contradictory person. On July 10, one of the squadron’s Spitfires had gone down over water. The squadron commander, hoping the pilot might be alive and drifting in a life raft, ordered a search for him, but Beurling went off on his own to hunt for enemy planes instead. He found two Macchi fighters and shot them both down in seconds. He fired just two bursts and hit both planes in the fuel tanks. While he abandoned his part in the search for the missing pilot, he also conscientiously and diligently honored another pilot’s request to deliver a Maltese lace tablecloth to the pilot’s mother in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, a delivery he made when he was sent back to Canada.

A Failed Public Relations Tour

Beurling did not have much time for reflection. A new set of problems was coming, since he was now famous in his home country. He was ordered by Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to return to Canada and campaign on behalf of the Third Victory Loan Fundraising Drive. Beurling must have been aware of the irony; while he had been rejected by the RCAF, he was now Canada’s most celebrated hero.

Exhausted, his wounds not completely healed, Beurling returned to Canada and to a personal public relations debacle. He was still in pain as he began to campaign on behalf of the Third Victory Loan. He was a poor public speaker; he said so at the beginning of many of his speeches. He had no feel for socializing or public relations. He was openly hostile to a group of Girl Guides who honored his kills by presenting him with red roses. Similarly, he was antagonistic when a reporter asked about bond sales and replied: “If I were ever asked to do that again I’d tell them to go to hell or ask for a commission on the bonds that I sold.”

Honorable Discharge For a Misfit Pilot

Behavior such as this resulted in Beurling being quietly but quickly sent back to England. The RAF made him an instructor, but Beurling had neither aptitude nor patience for teaching. He demanded to join a combat squadron, a demand the RAF initially rejected. An angry Beurling applied for admission into the RCAF, which, still embarrassed by having rejected him in 1939, eagerly accepted him. He was posted first to 403 Wolf Squadron, RCAF, which was engaged in regular combat sorties over France. The Allies were sending as many as 50 Spitfires over enemy territory at one time and only one in four of these sorties met Luftwaffe resistance. This type of air war was not what Beurling craved. He could not win glory.

Beurling began breaking formation and going off on his own in search of German fighters, but in doing this he left his wingman exposed to great danger. It was during this period that he fired his shotgun at his wing commander’s Tiger Moth. He shot down one FW-190 while serving with 403 Squadron and later was posted to 412 Squadron, RCAF, where he shot down another FW-190, his last kill in World War II.

Beurling’s constantly worsening behavior became intolerable to the RCAF. Events reached a climax when Beurling flatly refused a direct order to stop buzzing the squadron headquarters. “You can’t tell me what to do,” he snapped at his commanding officer, then immediately went up and buzzed the headquarters again. Any other pilot would have been court-martialed immediately, but Beurling was Canada’s top ace. He was quietly sent home and given an honorable discharge.

Suddenly rudderless, Beurling tried to join the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF), but the Americans rejected him. They did not want a misfit either. He had married Diana Whittall, a Vancouver debutante he had met while on his Victory Loan Tour, but the marriage was doomed to failure. One reason for this was the interest Beurling showed in other women while still on his honeymoon. He tried various jobs and failed at them all. No commercial aviation company would consider him. He was too wild. For a time, Canada’s greatest air ace, a pilot with 32 confirmed kills, begged on the streets of Montreal.

Last Flight in the Service of Israel

However, in 1948, Beurling’s luck apparently turned. The newly formed state of Israel, under attack by its Arab neighbors, was struggling to create an air force. It was searching the world for planes and pilots. Beurling volunteered. At first there was some Israeli reluctance to taking him, but he was accepted. How this happened tells a great deal about the “Falcon of Malta.”

In the spring of 1948, Beurling offered his services to Ben Dunkelman, the Jewish agent in Montreal responsible for recruiting aircrew. When questioned, Beurling agreed to fly for standard pay and affirmed his sincerity with biblical teachings.

“I told him we had no money to pay him, no uniforms, and no airframes except for a few Piper Cubs,” recalled Dynkelman. “He said he didn’t care about the money. He already had offers from three armies who wanted him. He told me: ‘The Jews deserve a state of their own after wandering around homeless for thousands of years. I just want to offer my help.’”

Beurling even suggested he lead a group of pilots to Malta in an attempt to steal Spitfires from an RAF base. Despite some misgivings, Dunkelman believed Beurling truly cared about the cause rather than just the fight and signed him up.

Beurling never flew a fighter for Israel, however. On May 21, 1948, the Canadian-built Noorduyn Norseman aircraft he was taking to Israel crashed at Urbe airport near Rome. The reason for the crash was never really determined, but there was speculation that it was caused by sabotage. Beurling died in the crash and was buried in Rome, but his body was moved to Israel in 1950. He is buried along with four other Christian Canadian veterans who died fighting for Israel.

Whatever Beurling’s behavior, he should be remembered for what he accomplished to earn the name “The Falcon of Malta.” He flew his first Maltese mission on June 12, 1942, and his last mission on October 10, 1942. In 121 days, Beurling, while often flying more than one mission a day and suffering from malnutrition, illness, and exhaustion, was credited with 28 confirmed kills.

The “Screwball,” buried in a hero’s grave in Israel, was Malta’s top gun. (Read more about the greatest fighter aces of the Second World War inside WWII History magazine.)

I saw by chance George Beurling’s story on TV last night, and was very moved.

We Maltese owe such a lot to the bravery of these brave pilots, and particularly to the famous Ace’s.

My father Gerald Vincent Mattei was 13 years old when the WW2 began. It meant he could no longer attend school, and his family had to move from their family home in Sliema to rent a house in Mdina during the bombardment; which was considered much safer – the ports were main targets!

Sadly our family lost the main ferry service between Valletta and Sliema. The Alexandra Wharf was hit by bombs and the ferries were used as troop carriers after being stripped of brass and other valuable fittings.

My father’s older sister Alexandra was engaged to an English RAF Pilot who was shot down and killed. She later married George Borg Olivier who became Prime Minister of Malta and brought Independence to the Islands in 1964. Yours Sincerely, Alexander Bethune Mattei

Following our viewing the film about the volunteer pilots travelling to Israel to form the Israeli Air Force to defend it against attack by several Arab nations, I researched the history of CFO George Beurling.

Having lived in south London in ww2 and spent many long summers in Malta with my wife’s family, what this man achieved in his short time there must be a modern day miracle.

I understand his rebellious side and dislike of the ex public school officer class who at that time considered themselves an upper class.

This attitude is reflected after the war when sergeant pilots were no longer permitted to fly.

Directed to Alexander Mattei

I noted that your middle name is Bethune, and wonder if it were so because of Dr. Norman Bethune, who was born in Gravenhurst, Ontario, (a town mentioned in the story above) with which I am familiar because I spent a few vacation times at a resort in that town in Ontario’s Muskoka Lakes district. As well, I am quite familiar with the life of Dr. Bethune as I am an expat Canadian living in China where he is considered a saint with hospitals, medical schools and even streets named after him. Why were you given that name?

Buzz of the Orient