By Michael D. Hull

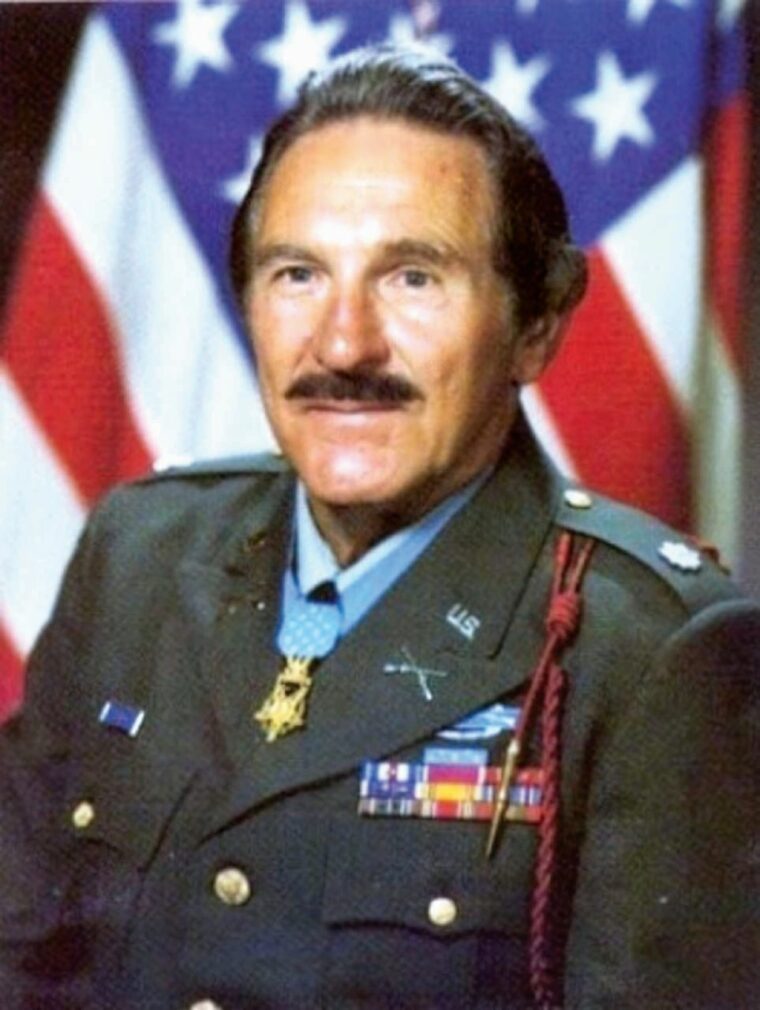

At a Washington, D.C., reunion of the 9th Infantry “Octofoil” Division, on Saturday, July 19, 1980, President Jimmy Carter presented the nation’s highest decoration for valor to Lt. Col. Matt Urban of Buffalo, New York.

“Matt Urban showed that moments of terrible devastation can bring out courage. His actions are a reminder to this nation so many years later of what freedom really means,” Carter declared, calling him “the greatest soldier in American history.”

As the visibly moved president turned to Urban, the Polish-American veteran struggled to hold back tears and maintain his composure. The proud moment was the finale to a long campaign for the medal in which the Disabled American Veterans pressed the Defense Department to review Urban’s overlooked but distinguished combat record.

The award of the Medal of Honor placed Urban alongside Lieutenant Audie L. Murphy, the boyish son of a Texas sharecropper who had been acknowledged as America’s most decorated soldier. According to the Army Personnel Command in Alexandria, Virginia, each received 29 medals and citations.

Matthew Louis Urban was born in Buffalo on Monday, August 25, 1919. His family was not poor, but money was scarce, so the boy worked hard during his high school years in order to help out. By saving extra money, he was able to enter Cornell University in 1937. He earned good grades, joined the ROTC, and excelled in sports. Boxing was his great love, and he became the university champion in three weight classes.

When he graduated in June 1941, Europe was at war and his neutral country was watching uneasily from the sidelines. “The winds of war were blowing pretty hard then, so I decided to join the Army,” he recalled later. After attending officer candidate school, he joined the 60th Infantry Regiment at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, as a lieutenant. “Immediately, I loved the military,” he said. His first assignment was as the base’s recreation officer and a boxing coach. His prowess in the ring became well known throughout the regiment.

By the time his regiment received orders for overseas shipment in the summer of 1942, Urban was a company commander. The 60th Infantry and other units of the 9th Infantry Division landed in northwestern French Morocco when Operation Torch, the Allied invasion of North Africa, was launched on Sunday, November 8, 1942. Activated in August 1940, the division was led by burly Major General Manton S. Eddy, who emerged as one of the outstanding American field commanders of World War II.

The 60th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Frederick J. de Rohan, went ashore at Mehdia and encountered heavy resistance while trying to capture the nearby airfield at Port Lyautey, a primary objective. But Lieutenant Urban, while eager to get into action, missed out on the initial assault.

Because of their special assignment as regimental boxing coaches, he and a sergeant missed shipping out with their regular unit and sailed to North Africa aboard the troopship Florence Nightingale. “My ship to Africa was a ship of outcasts,” Urban remembered. “You’d think a ship with a name like that would not be a fighting man’s ship, and it wasn’t.”

When the ship anchored off Morocco, Lieutenant Urban and the sergeant sought out a colonel and asked permission to be reunited with their own company on the beach. The colonel refused, telling Urban that he was “being saved for recreation assignments.” This was not what he wanted to hear; he had come to North Africa to fight Germans and not to box.

So, he and the sergeant jumped into a small rubber raft and made for the beach. “I remember the colonel yelling at us from the deck to come back,” Urban recalled. As he and the sergeant paddled, they realized that soldiers around them were drowning because of their heavy packs. Urban and the sergeant started pulling them out of the water and managed to drag a dozen GIs to shore.

Later that day, Urban caught up with his own company in the regiment’s 2nd Battalion, and he did not have to wait for his baptism of fire. “Our men were being shot up and killed fairly regularly,” he recalled. “During that first day of battle, we lost three sergeants. We paid the price for not being more experienced.” The regiment fought hard for three days before capturing the Port Lyautey airfield.

Lieutenant Urban and his comrades tasted combat and gained confidence. “Going over, we had boyhood visions that war was like cops and robbers,” said Urban. “But, wow, when we hit that shore, we woke up pretty quick.” His regiment saw plenty of action through the rest of 1942 and early 1943 against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Korps. While General Bernard L. Montgomery’s seasoned British Eighth Army pressed in from the east, the untried American infantry and armored units suffered a number of bitter setbacks, as at Sidi Bou Zid, Fondouk Pass, and Kasserine Pass.

But they learned quickly in the crucible of combat. “We became a war machine,” Urban recalled proudly. “My men were combat veterans now, and we had become quite good at what we did.” The subaltern from Buffalo swiftly developed an enviable reputation for his bravery and exceptional leadership. He always led from the front, was unflinching under fire, and cared for his men. Never asking them to attempt anything he would not do, he was popular and respected.

During one action, Urban’s F Company was assigned to capture a German-held hill in northern Tunisia. The Americans concealed themselves before outmaneuvering the enemy and taking the high ground. “For three days, we were surrounded,” Urban recalled. “Our company continued to hold this hill despite counterattacks by German regiment-sized forces. Finally, they gave up and withdrew to Bizerte.”

In March 1943, the 60th Infantry Regiment was attached to the 1st Armored Division, which captured Sened Station. The 9th Infantry Division faced difficult tasks in southern Tunisia that month. It had never made any kind of attack as a unit, and most of its troops had seen little or no action. The fighting across rocky crags and deep gorges was intense, and losses were heavy. But the division matured rapidly after its flawed performance at the Battle of El Guettar resulted in General Eddy incurring the legendary wrath of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, commander of the II Corps.

Lieutenant Urban, aided by First Sergeant John W. Miller, continued to inspire his men as the 2nd Battalion fought on, suffering heavy losses and winning a Distinguished Unit Citation. But sometimes the fearless Urban bristled when his weary young GIs faltered, as when F Company was ordered on April 23, 1943, to seize a German outpost atop Djebel M’Rata. Urban shouted, “Charge!” but no one moved. He called the NCOs together and said angrily, “We’ll try it again. This time, Sergeant Miller will follow up with his Tommy gun ready to shoot any son of a bitch who doesn’t move.” After a couple of minutes, the hill was taken with little enemy resistance, and only two men were killed by return fire. The regiment took Djebel Dardyss the next day and pushed on as the Germans withdrew to the strategic seaport of Bizerte.

While the 1st Armored and the 1st and 34th Infantry Divisions were busy in the southern sector of Tunisia assigned to the Americans, the fighting in the north fell to Eddy’s division. As it advanced toward Bizerte, the last major point of enemy resistance, it was supported by the motley French Corps d’ Afrique and tough Moroccan Goums. Late in the afternoon of May 7, 1943, a few hours after British infantry and armored units had marched triumphantly into Tunis, the 9th Infantry Division entered Bizerte. Men of Lieutenant Urban’s company were among the first foot soldiers into the town.

Urban won the Silver Star and oak leaf cluster for heroism in North Africa. Wounded three times, he also was awarded the first of seven Purple Hearts. After recovering, he braced with his company for Operation Husky, the massive invasion of Sicily by the British Eighth and U.S. Seventh Armies on July 9, 1943. The 9th Infantry Division landed at Palermo on August 1, pushed toward Randazzo, and took part in the offensive toward Messina.

For Urban’s company, the three-month Sicily campaign was a “silent march.” His men learned to move swiftly over rugged terrain at night, with full camouflage, while taking ground and eluding the Germans. Lieutenant Urban was nicknamed the “Ghost” because he stressed deception while trying to save his men’s lives. “Stealth and sweat wins more wars than force and blood ever did,” he explained.

After Sicily was secured and British troops launched the invasion of mainland Italy on September 3, 1943, the 9th Infantry Division was shipped to England in November to prepare for the planned Allied landings in Normandy. The division was spread in camps across southern Hampshire, with its headquarters in the cathedral city of Winchester. Friendly relations were established, and residents came to regard the 9th as “our division.” The freedom of the city was conferred upon the gruff yet good-natured General Eddy, who was viewed as a “Father Christmas figure” by local children.

Promoted to captain, Urban recalled, “We trained hard during our time in England. We all knew we were eventually going to hit the beaches in Europe and we would soon meet the Germans again.” The division was inspected in March 1944 by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Generals Dwight D. Eisenhower and Omar N. Bradley.

General Eddy’s division landed across Utah Beach on June 10, and the 60th Regiment went ashore on the following day. The division’s assignment was to advance westward with the 82nd Airborne Division, seal off the Cotentin Peninsula, and seize the strategic port of Cherbourg. As the regiment attacked toward the town of St.-Colombe on June 14, Captain Urban’s company moved inland to reinforce troops pinned down in hedgerows outside the village of Renouf.

The situation was desperate as two German tanks and small-arms fire raked the position and inflicted heavy casualties. Fearing that his company was in danger of being decimated, Urban grabbed a bazooka from a wounded soldier and worked his way forward under fire with an ammunition carrier to a point near the panzers. Standing up and exposing himself fearlessly, Urban calmly aimed the bazooka and blasted both tanks. Responding to his action, the company moved forward and routed the Germans.

Attacking near the village of Orglandes later that day, Urban spotted another panzer nearby. He tried to leap through a hedgerow, but a shell from the tank’s 37mm gun tore into his leg. He refused evacuation and led his company to its objective, a road junction, before taking up defensive positions for the night. At five the next morning, Urban led another attack, and an hour later he was wounded again.

One of his wounds was serious, and Urban had to be carried on a litter. When the battalion surgeon examined him, he said, “Captain, why are you still here? I’m sending you out for immediate evacuation.” Determined to stay with his men, Urban again refused, but the major insisted that it was an order. So, the irrepressible Urban was carried away and shipped to a hospital in England.

While he was recuperating restlessly for several weeks, his regiment helped to spearhead the 9th Division’s final assault on Cherbourg in late June. Captain Urban was distressed to see men from his company coming back wounded. The losses, he reasoned, were because of the lack of combat hardened officers. He was eager to get back to France, but walking was still difficult and the doctors would not release him.

Urban then saw a new challenge to occupy him—leading his own “dirty dozen.” Near the hospital was a tented camp of GIs who had deserted from their units. “These guys were true misfits,” Urban recalled. “They would hardly ever say ‘sir.’ They had no discipline.” They spent their time brawling and playing dice, but Urban told their colonel that, because of his experience as a recreational officer, he could work with them. The colonel agreed, and placed Urban in charge of 40 misfits. The captain tried to instill some discipline and made them get haircuts. “They sure did a lot of screaming and yelling,” he said. Urban was determined to get them across the English Channel, but they were also his ticket back to his own men.

One day in mid-July, Urban was visited by a wounded man who told him that F Company had been reduced from a first-rate combat unit to a demoralized bunch of frightened men. Still weak and bandaged, Urban deserted his hospital bed that night, rounded up his misfits, and crossed the Channel. “On our way over the Channel to France, some of these guys actually went overboard to escape the fighting,” he reported. “It was incredible.”

On a Normandy beach, Urban turned his remaining charges over to a lieutenant, wished him luck, and disappeared over a hill as quickly as he could. “I didn’t want him to figure out what he had while I was still around,” said the captain. He hitched a ride aboard an ambulance heading for St.-Lo, and then rode a mail jeep toward the 2nd Battalion command post. He arrived at 11:30 a.m. on the morning of July 25. A sergeant recalled, “The sight of him limping up the road, all smiles, raring to lead the attack, once more brought the morale of the battle-weary men to the highest peak.”

Urban was fighting mad. He reported, “I was full of anger, remorse, and despair. I’d seen my men mutilated, chopped up. I was seeking revenge. I was like a tiger. It was all bubbling up inside of me, and it exploded.”

Arriving at the battalion command post, Captain Urban learned that his unit had jumped off half an hour earlier in Operation Cobra, the American breakout from the Normandy beachhead. After a massive Allied carpet bombing, and while the British Second Army advanced southward in the Caen-Falaise area, General J. Lawton Collins’s VII Corps attacked west of St.-Lo. The fighting was to be bitter and losses heavy.

With a makeshift crutch in one hand and a .45-caliber pistol in the other, Urban limped forward to take command of his company and some other troops who were pinned down on a road by strong enemy fire from a ridge. It was a desperate situation. “The troops were frozen on their stomachs in fear,” the captain recalled.

After pulling a wounded man from a burning tank, Urban shouted to his troops, “Who’s in charge here?” No one responded. “You men are dead ducks if you don’t move,” he yelled. “The Germans are on the ridge, zeroed into this position. Follow me. Let’s get out of here!” About 40 troops scrambled after him, taking up new positions off the road and out of the line of fire. Urban tried to restore their spirit and steel them for an attack. A young sergeant reported later, “One of the craziest officers suddenly appeared before us, yelling like a madman and waving a gun in his hand. He got us on our feet, though, gave us our confidence back, and saved our lives.”

That evening, the battalion launched an assault on the ridge but was stalled by heavy fire. Armored support was needed. Two supporting Sherman medium tanks had been destroyed, and a third was undamaged but stuck in a hedgerow. Urban and his men were still pinned down, and the enemy fire increased. When a tank lieutenant and a sergeant were killed while trying to reach the intact tank, Urban crawled forward “like a snake, very slowly” and climbed aboard. As enemy rounds ricocheted around him, he raised his head from the turret, armed the tank’s .50-caliber machine gun and sent well-aimed bursts of fire against the German positions.

Urban was tearful and sure that he “was headed for certain death.” He wept and told himself, “Goodbye, world. God help me.” But he was unscathed and kept shooting while a crew scrambled aboard and managed to get the Sherman moving. With its 75mm cannon firing, the tank clanked up the ridge. Inspired by Urban’s daring, his men scrambled to their feet and followed. The disbelieving enemy troops were now being cut down by withering fire, and their position was destroyed.

“The Germans went from being the hunters to being the prey,” Urban reported, “and we just started pulverizing them.” That day, his company made the farthest advance of the St.-Lo breakthrough. The unit halted when a colonel radioed Urban, “Hold it, Captain. You’re getting too far out front. Consolidate your position.”

Urban had been lucky, but he was wounded again on August 2 when hit in the chest by shell fragments. Again, he refused evacuation. Four days later, when its commander became a casualty, Urban was chosen over officers senior in rank and age and given command of the 2nd Battalion. Then, while leading an attack on August 15, the indomitable Urban was wounded for the sixth time. Again, he defied the advice of Major Norman Weinberg, the battalion surgeon, and stayed with his men.

The battalion fought its way through France and into Belgium. One day, Urban and his men were dug in on a slope near the River Meuse when they saw several Germans in a command car approaching. They were reconnoitering to see where the Americans were sited. Urban told his men to hold their fire until the car got close to the river. “When they got close to us, we gave them a nice welcome,” Urban recalled later. “They sure were surprised to see us so close.”

The Germans stood in the car when they saw the G.I.s. Urban’s men shouted, “Surrender, surrender!” The enemy soldiers swung the car around to try and escape, but the Americans cut them down with M-1 rifle fire. A resourceful sergeant jumped into the command car and drove it back to Urban. “Cap, we got transportation for you now,” he said proudly. “You have a car.” The captain, who was still having difficulty walking, smiled appreciatively. The vehicle was soon put to use. Wearing an Army Air Forces jacket that he had bought earlier by trading a Luger pistol, Urban was later driven by the sergeant to a battalion commanders’ meeting.

The wide, shallow River Meuse near the town of Heer was a critical location in the Allied armies’ drive toward the German border. The bridge there had been blown up, and Urban’s battalion was ordered to establish a crossing point. The enemy had concentrated heavy forces in the area.

The battalion started across the river early on the morning of September 3, and the leading elements were broken up by a fierce barrage of enemy artillery, mortar, and small-arms fire. Captain Urban left his command post and led the disorganized GIs across the river and open terrain toward their next objective, the hillside village of Phillipsville. A German machine-gun nest halted the battalion.

When a sergeant died while trying to knock out the nest, Urban led a charge against it. “I moved faster than I ever moved before,” he recalled later. He tossed two hand grenades, and the second was a direct hit. But Urban fell when a machine-gun round tore a large hole in his neck. It was his seventh wound, and he lay on the ground conscious but bleeding profusely.

Under heavy fire, he was dragged to a roadside ditch, where the battalion surgeon hastily performed a tracheotomy so that the captain could breathe. He was still conscious when a Roman Catholic chaplain arrived and asked the surgeon, “Any hope?” Major Weinberg shook his head. “Thanks a lot,” Urban recalled thinking. “I felt like dying right there.”

While his battalion continued their advance, Urban was laid on the hood of a jeep and driven to a field hospital tent. He was kept there, unable to talk, for six weeks. When the doctors saw that he was not going to die, Urban was shipped to a hospital in England. Eventually, after more recuperation, he cajoled doctors into giving him a five-day convalescent pass to Scotland. They agreed, and he left instantly—but not to the Highlands. Refusing to let seven wounds keep him out of the war, the gallant captain was determined to rejoin his men.

Voiceless and still in pain late in 1944, he spent two nights sleeping on a bench while waiting for a chance to hitch a plane ride to France. Unauthorized flights had been banned after the loss of Major Glenn Miller’s plane in the English Channel, but Urban was able to “hook up with some Air Corps guys who were sweethearts.” They helped him to stow away aboard a plane and cross the Channel.

Communicating by writing notes, he hitched rides in trucks and jeeps while trying to reach his battalion, which was now fighting its way toward Berlin. It was a grueling journey, but Urban managed to reach Amsterdam and eventually catch up with his surprised men. They wanted him to stay, but the regimental commander told Urban, “You’ve had enough.”

After being allowed to stay for five days, he was sent back to England. The war was over for Matt Urban, but his heroism had made him a U.S. infantry legend in the European theater. He recovered from his wounds but spoke in a raspy voice because of damaged vocal cords. Urban was promoted to lieutenant colonel in October 1945, and received a medical discharge five months later.

Besides campaign ribbons, his decorations included the Silver Star with oak leaf cluster, the Legion of Merit, the Bronze Star with two clusters, the Purple Heart with six clusters, a Presidential Unit Citation, two Croix de Guerre Medals, the Belgian Fourragere, and the prized Combat Infantryman Badge.

When he was repatriated in July 1945, Staff Sergeant Earl G. Evans, who soldiered with Urban in North Africa and Europe, wrote to the War Department and recommended him for the Medal of Honor. The letter was forwarded to Major General Jesse A. Ladd, commander of the 9th Infantry Division, then on occupation duty in Germany. It never arrived, but a copy of the recommendation was placed in Urban’s personnel file. The hero knew nothing of Sergeant Evans’s efforts on his behalf.

After the war, Urban lived peacefully and took up social work in Michigan. He served as the Port Huron recreation director for seven years, ran the Monroe Community Center for 16 years, and wound up as the civic and recreation director in Holland. He took time out to speak to veterans’ groups across the country and to write and promote his autobiography, The Matt Urban Story: Life and World War II Experiences.

Efforts had been underway in the Polish-American community, meanwhile, to have Colonel Urban honored with the nation’s highest decoration for valor. At a 9th Infantry Division veterans’ reunion in 1977, he learned of Sergeant Evans’s letter, and a campaign supported by the Disabled American Veterans and the Polish-American Congress in Washington was launched. This prompted the Defense Department to review Urban’s combat record. When Pentagon officials admitted that his exploits had been mistakenly overlooked, President Carter took a personal interest and acted to ensure that Urban received the Medal of Honor.

“When I came home, I never thought about war,” Urban remarked in 1988. “That’s why the medal was 35 years late … I just never pursued it.”

Matt Urban collapsed while working in his Holland office on Friday, March 3, 1995, and died of complications from a collapsed lung—resulting from one of his war wounds—the following day in the Holland Community Hospital. He was 75.

After a funeral Mass at St. Francis de Sales Church in Holland on March 7, Colonel Urban was buried near the Memorial Amphitheater and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldiers in Arlington National Cemetery. He was survived by his wife, Jennie; a daughter, Jennifer, and a brother, Stanley.

The late Michael D. Hull wrote on a variety of topics for WWII History. He resided in Enfield, Connecticut.

Thank God for men with such courage and determination.

Amen.