By David H. Lippman

The word itself was bland. “Motti” is Finnish for a “bundle of sticks,” but the theory was how the tiny armies of Finland would deal with the long columns of Soviet troops that had been storming down the roads and logging the trails of that nation’s sub-Arctic wilderness since the Russo-Finland War broke out on November 29, 1939.

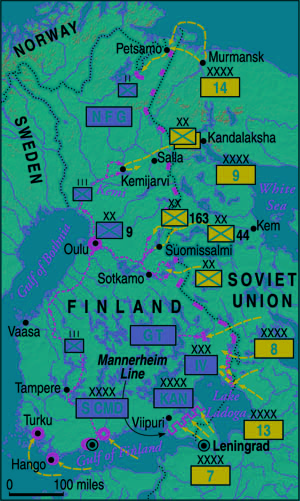

Joseph Stalin’s blatant war of aggression pitted the Soviet Union’s 105 million people against Finland’s three million in a brutal drive for land and power. But when Stalin’s troops and tanks butted their heads uselessly against the Finnish troops defending the Mannerheim Line (named for their commander in chief, Baron Gustav Mannerheim), Stalin decided to put the pressure on Finland’s central belt, sending the 9th Army toward Oulu via the small town of Suomussalmi. The 9th Army’s spearhead was the 163rd Infantry Division and the 44th Motorized Infantry Division, whose troops were well equipped with tanks, armored vehicles, artillery, and even a motorized brass band to maintain morale. But it lacked skis, sleds, and winter-trained troops. These were fatal weaknesses, and the Finns, despite their small numbers, knew how to exploit them.

The “motti” would enable the Finns to deal with a long column of Soviet road-bound troops in their nation’s wilderness. It had three phases:

Phase 1: Reconnaissance to fix the Soviets and encirclement to prevent them from moving, thus pinning them in a narrowly circumscribed area.

Phase 2: Quick, sharp attacks with concentrated force to gain local superiority or equality at vulnerable points in the column, to split it into isolated fragments.

Phase 3: Destruction in detail of each pocket in turn, weakest first, so that the strongest ones, cut off from their supplies, would wither in the cold and become weaker before being destroyed.

The Finns benefited from the Soviet forces being unable to maneuver off-road. They also benefited from the fact that Joseph Stalin had gutted three quarters of the Soviet Army’s leadership before the war, replacing them with men who were politically reliable but militarily timid at best and utterly incompetent at worst. Further, every decision made by a Soviet combat officer had to be approved by a “Politruk,” a frontline commissar, who would ensure that the plan would be “politically sound,” regardless of its military merits or lack thereof.

The result was a Red Army that was overly disciplined and utterly lacking in initiative at every level and inept in such critical skills as camouflage and skiing.

The “motti” tactic, however, had weaknesses. First, it could only be used against Soviet forces that had actually strung themselves out along a road in sub-Arctic Finland, which was not a given. Second, it meant giving up terrain to the invaders. Third, it required time for the Finns to make reconnaissance, assemble troops, cut through the weak defenders, and whittle down and starve out the Soviets. And whatever faults the Soviet Army had on the offense, its men were equipped, formidable, and determined when seeking to hold their ground. They could inflict casualties on the Finns that could not be replaced.

The “Politruks” told the men that any ground they held was “Soviet” and had to be defended as a part of the Motherland, and Soviet troops did so.

Suomussalmi was a small, provincial town of 4,000 loggers, hunters, and their families surrounded by forests and lakes in the central wilderness of Finland. It stood directly along a road from the Murmansk-Leningrad rail line to Oulu on the Baltic Sea.

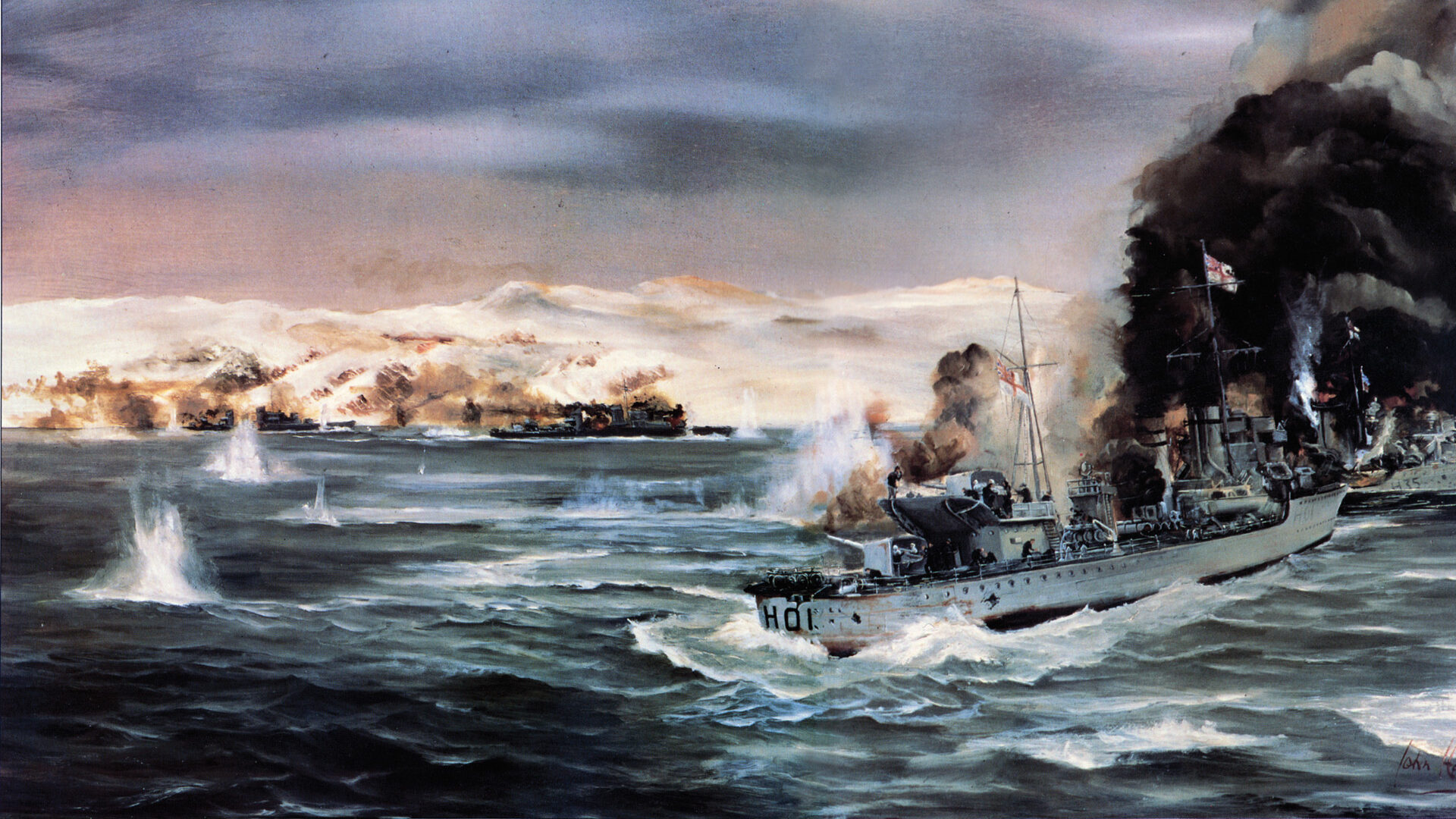

With the Baltic Sea frozen over, there were only two ways to ship supplies into Finland—by rail from Sweden, through Oulu, or behind a convoy of icebreakers to the Finnish port of Turku. The Finns had the world’s largest fleet of icebreakers and two coast defense battleships at Turku to keep that port open, but it was dangerous for foreign powers to ship in supplies through a Baltic Sea dominated by Soviet and German planes and warships.

If a Russian force could drive down that road to Oulu, the Soviets could divide Finland in two and also cut Finland off from its land source of supplies in Sweden. Yet the Finns lacked sufficient forces to block the road. The Soviets had more than enough to storm down it, turning the job over to Corps Commander V. Dukhanov’s 9th Army and his five divisions. Oddly enough, when Finland’s Baron Mannerheim served in the Imperial Russian Army, he had been in the 9th Army. The Soviets did not bother to change army designations.

Two roads led to Suomussalmi from the Soviet frontier. To the north was the Juntusuranta Road from the settlement of that name on the Soviet border, which joined a major north-south artery that led through Suomussalmi to Hyrynsalmi in the south and Peranka to the north. The southern track was the Raate Road that went straight to Suomussalmi. The Finns figured that any Soviet attack on Suomussalmi had to come that way.

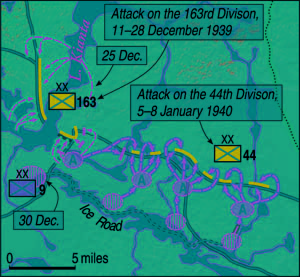

Major General Andrei Zelentsov’s 163rd Rifle Division, drawn from Tula, a city north of Moscow, was ordered to take the lead. Zelentsov put his 662nd Regiment on the Juntusuranta Road, which gave him complete surprise. The Finns opposed this regiment with ROII, a 58-man unit of border guards under Civil Guard reservist Lieutenant M. Elo, a 22-year-old schoolteacher. The Soviet division’s other two regiments, the 759th and 81st, drove down the Raate Road, which was defended by two platoons of border guards and some improvised roadblocks. Even so, the Raate Road force drove only six miles on the first day of attack, December 5, 1939.

The slow Soviet progress gave the Finns time to evacuate Suomussalmi’s civilian population, burn some but not all of the town’s buildings, and rush in reserve companies from Kajaani to delay the invaders.

Meanwhile, Zelentsov’s two regiments on the Juntusuranta Road made better progress, forcing the Finns to send in Major I. Pallari’s ErP-16—the 16th Independent Battalion—to hold the ground. They reached Peranka at 1 amon December 6 and started setting up a defensive line. As soon as they did, Colonel Sharov’s Soviet 662nd Regiment showed up and began probing attacks. After 24 hours of vigorous skirmishing, the Finns held the Russians in check. Pallari himself was badly wounded.

All Finnish forces came under command of Lt. Col. Paavo Susitaival, a member of Parliament, Great War 27th Jager Battalion veteran, and peacetime reservist. He placed all forces fighting against the 662nd under his command in Task Force “Susi,” but first requested permission from the Finnish Parliament to be absent from its sessions while he performed his military duties. He got that permission without delay.

Mobile Finnish radio intercept teams listening to Soviet message traffic quickly learned that the 662nd was on the defensive. The Soviets used simple codes and sometimes sent messages uncoded. One such message from Sharov, sent on the 11th, reported to Zelentsov that his regiment could not advance easily as it lacked felt boots (valenki), snowsuits, and rations. Other messages told the Finns that one of Zelentsov’s Politruks, named Boevski, had been “fragged” by some of his men. A third message, on December 13, reported 48 frostbite cases and a need for 160 replacements for men lost to Lieutenant Elo’s roadblocks. Other messages warned that his officers “could not handle their men.”

The Finns were amazed. Clearly the 662nd Rifle Regiment was not a particularly tough force. That point was proven when Sharov sent his men into an attack on Ketola village, which failed with a loss of 150 men. With that, Sharov’s regiment was finished—20 percent of his men were out of action from bullets or frostbite. He went over to the defensive for the rest of the battle.

With the 662nd out of the game, the Finns concentrated on the two regiments headed straight for Suomussalmi, entering the remains of the town on December 7. Mannerheim appointed Colonel Hjalmar Siilasvuo, another one of his Jager Battalion protégés, to head there with his JR-27 (27th Infantry Regiment) to take over and defeat the Soviets.

Short, blond, blunt-speaking Siilasvuo was another capable citizen-soldier, a newspaper editor’s son, and peacetime lawyer. But JR-27 lacked any antitank or antiaircraft guns and had no artillery at all. It also lacked tents and snowsuits. But all the men had all their skis, and the troops were from small towns in the area and understood the value of mobility.

Siilasvuo wasted no time. He headed straight to Suomussalmi and reported to Maj. Gen. W.E. Tuompo, the sector commander, at Kajaani, on December 8. Tuompo had just arrived himself. Even so, the Finns moved decisively. JR-27 and its associated units were within 2.5 miles of Suomussalmi by December 10.

Meanwhile, at the town Lieutenant Elo’s exhausted Civil Guardsmen were crumpling under the Soviet attack. His men had taken 50 percent casualties, and Elo shot himself in despair that day. ROII lacked radios, so they had no idea that help was on the way and could not stand up to the attacking tanks.

Aware that the defenses were hanging by a thread, Siilasvuo set up his tactical headquarters in a forester’s home in Hyrynsalmi village on December 10, at the end of the rail line, which enabled him to receive supplies and reinforcements. By day’s end, he was planning a counterattack with all three of JR-27’s battalions, plus two battalions of covering troops who had been fighting there since November 30, including Elo’s men.

To boost morale, Siilasvuo told everyone that his force was the lead element of the 9th Division, a new force. Mannerheim backed the move. He later declared the scattered units to be the 9th Division, putting Siilasvuo in command.

Next, Siilasvuo moved JR-27 to an assembly area southeast of Suomussalmi, where it would lay down an “ice road.” That consisted of scraping clear a path in the ground and flooding it. The smooth surface that resulted was perfect for soldiers to move rapidly on skis and haul supplies on sleds. The Finns were able to bring up their scarce artillery, move it from point to point, fire off some shells, damage the Soviets, and pack up again to avoid being spotted.

Siilasvuo’s plan was to cut the road between the 163rd and the Soviet border and then crush the Soviets. The 163rd’s commander did not seem aggressive or imaginative, so Siilasvuo was betting that his men could show more aggression and initiative in attack than his opponent.

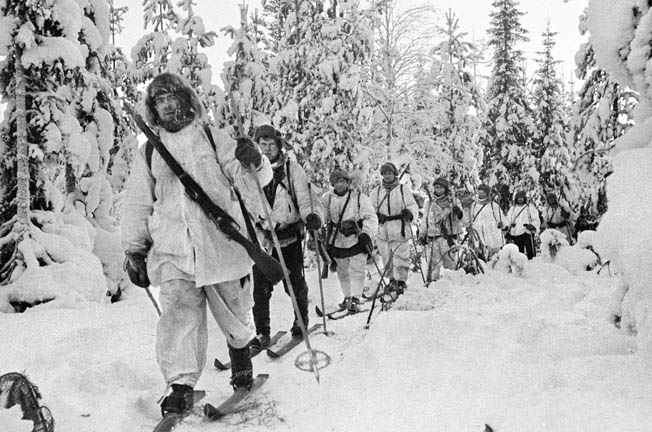

With the ice road laid, JR-27 began sending out patrols to find the best approach routes to the road and secure them by positioning pickets of ski troopers on the flanks. Then the attack teams would move into final positions, where they would shed their heavy gear, leaving it under guard. Wearing only lightweight snowsuits and carrying as much firepower as possible, the attack teams would move in as close as possible to the enemy.

The attacks would start with a quick barrage of mortar and machine-gun fire. After a few moments, the fire would be shifted 100 yards to the right and left of the target to give the attackers a sealed corridor in which to attack.

The Finnish infantry would then attack, hurling grenades and gunning down foxholes, tents, and trucks. Other Finns, equipped with satchel charges, would hurl them into vehicles, open tank hatches, field kitchens, and mortar pits to cause general destruction. Sharpshooters were to cut down officers.

With the Soviets then reacting, the Finns would withdraw as quickly as possible. The goal was not as much to kill Soviet troops as to cut breaches in the column and damage or destroy the Soviet supporting arms that fed and led the frontline troops.

Once breaches were created in the Soviet column, additional Finnish troops, more heavily equipped, would charge into the hole and create barricades and earthworks, even flipping over wrecked Soviet vehicles to do so. The Soviets, unable to dig trenches in the permafrost, could only knock down trees to create their own defensive barriers.

Siilasvuo and his men launched their attacks on the 12th and set up their main roadblock to the east at a natural chokepoint between Lakes Kuavasjärvi and Kuomasjärvi, under Captain J.A. Mäkinen. The Finns set up heavy machine guns between the frozen lakes, knowing that the Soviets had a choice—drive across the frozen lakes, dismount from their vehicles and drop off their heavy equipment to move through the woods, or attack the machine guns head on. The Finns knew it would take a major Soviet drive to hook up with the 163rd, now trapped at Suomussalmi.

Zelentsov knew he was trapped. He was sending panic-stricken messages to his superiors, and the 44th (Ukrainian) Motorized Rifle Division, under Commander Second Rank A. Vinogradov, was ordered to drive west to relieve the 163rd. But the 44th attacked according to the Finnish plan—down the road—and a bare 350 Finns held off 17,000 Soviets.

Despite its heavy equipment, the 44th was no elite outfit. GRU Captain Ismael Akhmedov, a Politruk assigned to the division, drove up the division’s column and found the men unenthusiastic. “Their faces were sullen, their bodies tired, their spirits low. Men, machines, artillery, tanks, horses, all moving toward Suomussalmi, most of them, it proved, to destruction and death.

“At one stop among those troops, a soldier, a simple Ukrainian peasant from the Poltava area, asked me a question: ‘Comrade Commander,’ he said, ‘tell me, why do we fight this war? Did not Comrade Voroshilov declare at the Party Congress that we don’t want an inch of other people’s land and we will not surrender an inch of ours? Now we are going to fight. For what? I do not understand.’” One of Akhmedov’s fellow Politruks interrupted and told the soldier about “the Finnish danger to Leningrad.”

Worse, by intercepting uncoded Soviet messages, the Finns knew exactly when and where the 44th would come. The messages told the 44th’s commander, Vinogradov, that he was to fortify the Raate Road as he advanced along it. But the head of 9th Army’s Operations Department, Colonel Ermolaev, “edited” the messages sent to Vinogradov, so he never got that one.

To make matters worse, due to transport shortages, Vinogradov’s reconnaissance teams reached the line of departure on foot and behind the armor and artillery. The 44th streamed up the Raate Road with the wrong units in the lead.

On December 23, Mäkinen abandoned his strongpoint and attacked the leading 44th Division force, the 25th Regiment. The entire Soviet division, advancing on a one-tank front, ground to a halt, jamming thousands of vehicles, horses, men, and its motorized brass band on a single track amid worsening weather.

Meanwhile, Siilasvuo turned on Suomussalmi. The town stood in two pieces, surrounding a frozen lake. The 163rd Rifle Division was suffering from the -25 degrees C temperatures, food shortages, and Finnish fire.

First Siilasvuo sent in sharp raids against the road leading north from Hukoniemi and against the town’s western outskirts. Two Soviet T-28 tanks attacked a Finnish squad caught in lightly wooded terrain near the village. Lieutenant Hovinen taped five stick grenades together and crawled to the tanks, while his buddy, 1st Lt. Virkki, tried to provide covering fire with his 9mm Lahti automatic pistol, firing at the tank’s observation slits. The T-28 fired at Virkki, and he hit the dirt to load another magazine into his weapon. Then he popped up and fired more bullets at the T-28. Three times this scene was played out. Finally the Soviet tankers grew frightened of the crazy Finn and began to pull back.

At that moment Huovinen pointed his grenade bundle at the tanks, and they put on speed to retreat. Incredibly, a two-tank attack had been repulsed by pistol fire.

Finnish battlefield leadership was a hallmark of their counterattacks. Another lieutenant named Remes reacted to taking a bullet in his hand by turning over his command to a subordinate, making a few jaunty remarks to his men, and sauntering off to an aid station. He never arrived. Just after dark the next day, his body was found in the deep woods. He had apparently run into a Soviet patrol that now lay around him—six dead Russians.

On December 26, Siilasvuo received artillery support in the form of a four-gun battery of 76mm guns that predated the 1904 Russo-Japanese War. But they could still fire. On the 28th, he received a more modern battery, and on January 2, 1940, a pair of Bofors antitank guns. On the 22nd, he received something else more substantial, official command of the 9th Division. On Christmas Day, he got Infantry Regiment JR-64, a newly organized battalion of ski guerrillas designated P-1 and an independent battalion of infantry. With 11,500 men, he had a considerable force to address the surrounded 163rd.

To the north, Task Force Susi was still facing the 662nd Regiment with help from Bicycle Battalion PPP-6. Their job was to clear out some Russian cavalrymen operating along a primitive road between Lakes Alajärvi and Kovajärvi just two miles northwest of Suomssalmi. They did so, and PPP-6 was assigned to Siilasvuo after that.

On December 23, Mannerheim provided Task Force Susi with JR-65, a new regiment that rode in trucks 100 miles from Oulu in -25 degrees C weather. Positioned on the north shore of Lake Piispajärvi, the regiment drove back the enemy as far as Haapavara by Christmas.

At Suomussalmi, Zelentsov decided he had spent enough time in the trap and ordered a breakout on Christmas Eve. Backed by his two artillery regiments, the 86th and 356th, Zelentsov attacked the Finns at 11 am, damaging their phone lines, and began moving at noon. Colonel Mäkiniemi’s two covering battalions stopped the breakout, and the Soviets withdrew. On Christmas Day, the 163rd tried again, this time attempting to cross the frozen Lake Vuonanlahti to the west. The Finns were baffled. Were the Soviets trying to make a loop around the Finns or were they just lost? The Soviets later claimed that magnetic ores in Finland’s lakes led their compasses astray. Others said the compasses simply did not work.

Even so, the Soviets charged across the ice in brown uniforms—they wouldn’t get any snowsuits until January—and came under heavy Finnish automatic fire. Soviet soldiers died on the ice, and the rest fell back to the wrecked village. By now the 163rd was running out of ammunition as well as food.

On December 27, Siilasvuo launched his final assault, backed by all eight of his artillery pieces. He sent his men across the frozen Lake Vuonanlahti to outflank the Soviets.

But the Soviets proved tenacious in defense despite their hunger, cold, and lack of ammunition. For three days, Siilasvuo’s men fought against the Soviet pockets, but at noon on New Year’s Eve, the Soviet defenses cracked, and the 163rd’s men began breaking into groups, fleeing in all directions, mostly across the frozen Lake Kiantajärvi toward their main supply dump. In their brown uniforms, the Soviets made excellent targets.

At this point, the Finnish Air Force made a rare appearance, as two of its British-made Bristol Blenheim bombers swooped in and dropped bombs on the ice, smashing holes that sent men, vehicles, horses, and sleds into the lake.

With nowhere to go, Soviet troops fled into the wilderness, often dying of exposure and exhaustion, or surrendered where they were. Those who went in the Finnish bag were relieved to be taken as they were suffering from frostbite and fear. They told their captors about bad Soviet food, bad Soviet treatment, and bad Soviet leadership. One prisoner said he had been visiting a shop in a little town on the Murmansk Railroad near Leningrad just before the war broke out, buying his wife a new pair of shoes. A local commissar spotted him and dragooned the man into the army on the spot, hoisting him by his coat lapels and asking to know why such a fine specimen of Soviet manhood was not marching to the aid of the oppressed Finnish proletariat.

The prisoner marched into Finland without one hour’s formal training and was captured, his wife’s shoes still in his pack. The Finns gave him fresh socks, cigarettes, and time in the sauna. It was the first time in four weeks he had seen soap and water. After that, they kept him as a kind of headquarters mascot and translator for the rest of the campaign.

As the 163rd disintegrated, the victorious Finns took 500 prisoners and began assessing their booty, which included large amounts of ammunition, 30 field artillery pieces, three dozen antitank guns, shoddy cotton uniforms, inadequate footwear, distinctive Soviet conical caps known as budenovka,inedible dehydrated millet gruel and pork fat rations, which offended the Muslim soldiers in the Russian Army, and some empty vodka bottles that were good for Molotov cocktails. There were 5,000 corpses on dry land.

Zelentsov was among the dead, but his body was never identified. The best theory was that he shredded his general’s identity papers, put on an enlisted man’s uniform, and tried to break out into the woods, dying anonymously in the crossfire or in the snow. Either way, he vanished from history, which was probably lucky for him—Stalin’s secret police had little use for generals who failed their assignments.

Now it was time to dispose of the 44th Motorized Division, whose tip was two miles from the Suomussalmi battlefield. Its men could hear the shooting and comrades dying. The 44th was strung out along a 20-mile stretch of the Raate Road and unable to move in any direction. They had thousands of pairs of skis dumped into their supply train at the start of the campaign, but nobody knew how to use them. A handful of men volunteered to ski into the forest on patrol, but they never came back. The rest of the division could only wallow helplessly in the snow.

The 1st Battalion, 27th Infantry Regiment (JR-27)—1,000 well-fed men under Lieutenant Lassila—was tapped for the job of starting to eliminate the 44th. They arrived 400 yards south of the Raate Road just east of Suomussalmi at 11 pmon January 1, 1940. From their start line, the Finns could see roaring log fires built by the miserable Ukrainian soldiers, desperately trying to stay warm.

Lassila set up two groups, each with six machine guns, about 500 yards apart and trained on the edges of the gap he wished to make. That would seal off the edges of his attack route. His target was the main part of the 44th Division’s artillery park. At his signal, the infantry charged the road while the machine guns opened fire. Engineers followed to blow up trees and create roadblocks to prevent the 44th’s vehicles from intervening.

The attack succeeded. Soviet sentries 60 yards from the road went down first. The Finns stormed across the road and right into an artillery battalion’s park, cutting down gun crews with grenades and short bursts. The Soviets hit back with fire from their mobile antiaircraft guns, but the Finns were too close for them to have any impact. The antiaircraft tracer went over the Finns’ heads, and the Finns shot down the Soviet gunners at point-blank range.

One hundred Russians were killed, and a tank, several trucks, and a field kitchen knocked out for the loss of two Finns. By dawn, the 44th had been decapitated. Its spearhead was cut off from its tail.

Siilasvuo decided to press his luck, sending his two Bofors guns across the ice roads and emplacing them by dawn, pointing east against the Soviet tip. Just as the guns got into position, the 44th counterattacked. In 15 minutes, the two guns blasted open seven tanks, jamming the road with burning wrecks and strengthening the new Finnish roadblock.

With that, the Finns began cutting the 44th into small, manageable “mottis” over the next few days. The Finns set up rings of command posts, supply depots, and camouflaged dugouts around each “motti” 5,000 to 1,000 yards from the Soviets to protect them from Red Army bullets. Finnish patrols would go out in the snow for two hours, harass the Soviets, and then hike back to their warm dugouts for four hours of rest, food, and sleep. After two or three days, each Finnish soldier would go to one of the frontline saunas, a national tradition and important morale benefit.

Finnish skiers would hit Soviet radio sets, command posts, gun pits, ammo points, and above all Soviet field kitchens. Finnish troops shot them up to deny the enemy hot food and then let them starve and freeze. Akhmedov wrote that his “battalion had been badly punished when the men had lit fires to warm themselves and heat food. From treetops the Finns had machine-gunned every fire, easily picking out the dark silhouettes of the men against the snow.”

Vinogradov did not even issue a counterattack order, but some of his men tried to break out to Russia on January 2. They came under flanking fire from the woods and were stalled. A captured Soviet colonel told the Finns it was like “butting our head against a stone wall … it was unbelievable.” The Finns wondered why the Soviets did not try simultaneous counterattacks east and west, but did not argue with Vinogradov’s passivity.

The same day, 3rd/JR-27 assaulted the road farther west near the Haukila farm. The Russian defenders were strong, and the Finns could only tighten their grip on them, using mortars to wipe out the Soviet field kitchens. More Finnish counterattacks went in from Sanginlampi farm against Soviet positions near Eskola. It took the Finns three days to clear out the enemy from those positions. On January 4, Task Force Kari cleared the enemy from that sector and had its hold on good terrain near Lake Kokkojärvi.

On January 3, the Finns built more ice roads, widened wagon tracks, and improved their surfaces. The next day, Siilasvuo attacked again. Task Force Mäkiniemi, consisting of JR-27, a battalion from JR-65, and ski-guerrilla unit P-1, hit the strongest remaining Soviet “motti” in the Haukila farm sector. Siilasvuo committed six guns—two thirds of his pieces—to this attack. Colonel Mandelin’s task force, consisting of two battalions of JR-65 and three additional companies, was to hit the Haukila section of the road from the north at the same time that Mäkiniemi’s men hit from the north. Task Force Kari would launch sharp flanking attacks against the Soviet positions from Tynnelä to Kokkojärvi, with its three infantry battalions and the last two artillery pieces. Finally, Task Force Fagernas would backstop the actions by cutting a road at the Purasjokie River and again near Raate village, a mile from the Soviet border.

By January 5, the 44th Division consisted of seven separate detachments. The biggest was a two-mile segment just east of Captain Mäkinen’s roadblock manned by a regiment of infantry, 20 armored vehicles, and most of the division’s artillery. Siilasvuo was going to break that portion into smaller and smaller elements and let them all freeze and starve before attacking each in turn.

Siilasvuo moved his men along his ice road south of the Raate Road in two task forces, one under Major Kari, the other under Lt. Col. Fagernas. Kari’s men went into a bivouac near Mäkälä, while Fagernas’s men dug in at Heikkilä. A third raiding detachment, a reinforced company, moved into position at Vanka, along a crude wagon track that led to Raate village.

Siilasvuo’s offensive went off on schedule against fierce resistance. Task Force Mäkiniemi’s men were pinned down short of the road by heavy Soviet fire. Captain Lassila’s men also took heavy casualties from Soviet artillerymen firing over open sights.

When these attacks failed, Lassila met a sergeant who had taken over his company when three senior officers had been killed or wounded and the sergeant himself had been shot in the lung. Lassilla asked how the wounded man was, as he lay back on his stretcher. The sergeant said it was easier to breathe with two holes in his chest.

Lassila’s battalion took 96 casualties in six hours, men it could ill afford to lose, and it had been dribbling away 10 percent of its strength each day. He believed his men had reached their limit. He asked permission to abandon his roadblocks, deploy in the woods, and block the road with fire alone.

When the request went up the Finnish chain of command to Colonel Mäkiniemi, the colonel was irate. All of his men were heavily engaged. He told Lassila that if the roadblocks were abandoned Lassila would be court-martialed and shot. Lassila got the point and held on.

Task Force Kari moved against the Kokkojärvi junction at 6 ambut could only get a quarter mile from the road intersection. Unable to deal with Soviet tanks or firepower, Kari withdrew to the forest.

Fagernas made the day’s best progress, blowing up a small bridge about 21/2miles east of Kikoharju. But he could not reach the main objective, the bridge at Purasjoki. Siilasvuo decided to reinforce success and sent troops to support Fagernas, which helped ambush a convoy of fresh NKVD troops sent over from Russia. With the reserves, Fagernas was able to detonate the Purasjoki Bridge at 10 pm. The river’s ice was not strong enough to support vehicle traffic, which helped seal off the Raate Road area from mechanized or truck-borne reinforcements.

Finally, Task Force Mandelin, on its own, wiped out some Russian patrols and established a blocking position on the secondary Puras Road to prevent breakouts on that route.

While the day’s showing was a poor one for the Finns, it put the Soviets under strain, and Vinogradov was unable to make a coherent breakout. The next day they tried to do just that anyway, attacking Lassila’s position. The Soviets drove herds of horses along the roads, hoping to clear Finnish mines and provide themselves with food. The callous slaughter sickened and angered the Finns, but they held their ground. Task Force Mäkiniemi fought its way through to the road in several places, knocking out Soviet positions one by one.

On the night of the 5th, Kari’s forces established another roadblock east of the Russian position at Kokkojärvi, which was in place by 3 am. It held fast against repeated Soviet attacks all day.

Another one of Kari’s units, ErP-15, took three hours in the heavy snow and dense firs to reach the road at a point east of Tynnelä. There they saw hundreds of Soviets fleeing toward the Puras Road. Siilasvuo reinforced the roadblock on that cowpath and chipped away at Soviet pockets.

Vinogradov called for air support and got it. Soviet fighters and bombers roared over the battlefield looking for targets to paste but could not find them easily. Soviet transport planes were even less successful. Three small scout planes dropped six packs of hardtack into an area where 17,000 men were going mad with hunger. By the time these parcels had landed, the men in the “motti” had suffered five days of -30 degrees C temperatures on barely cooked horsemeat.

Everything worked against the Russians in the battle, as in the war. Their 1902 model Moisin-Nagant rifles were single-shot bolt-action weapons that could fire 7.62mm bullets with great accuracy, but in temperatures below -15 degrees C their gun-oil lubricants froze. The Finns used the same weapon and same caliber bullet, but their gun oil was a combination of alcohol and glycerine.

The 44th Division’s vehicle engines had crankshafts that could not turn over when the temperature fell below -10 degrees C, so they had to be kept running all the time, using up fuel and lubricant and putting a strain on their batteries. The Russians learned from this failure. Their later T-34 tanks employed massive pump-driven compressed air reservoirs to turn over their engines.

Adding to the Soviet terrors were the long sub-Arctic winter nights, made darker by the endless fir trees. Soviet troops were denied sleep by the sound of Finnish bullets ricocheting off bark and hitting men and horses, which set off more agonized cries. Despite being a motorized division, the 44th had 2,500 horses, mostly Siberian panjes, to haul artillery and other equipment.

The Soviets had to cut down on campfires, which only made things worse. Men could not touch metal or they would be welded to it. They tried vodka to stay warm, but that didn’t help. The alcohol only opened their skin pores and reduced their body heat.

Politruk Akhmedov found that his men from the Ukraine were unprepared for a winter harsher than those of their native steppes. “All was terribly unreal. I thought of the haunted forests of the fairy tales of boyhood. I was very nervous but tried not to appear so. I looked at the faces of Nikolayev and the driver. They were ashen,” he said later.

Wounded men were doomed. Even a small injury (mostly frostbite) could prove fatal as the Soviet Army medics struggled in an unequal battle against gangrene. Freezing wounds mortified quickly, leaving medics with no option but to amputate. Soon stacks of shattered limbs appeared in piles outside dressing stations. As the Finns retook these areas, they were shocked by the tableaux of cold, bloody, amputated limbs, frozen bodies and excrement, and distorted corpses.

Vinogradov’s division was split up. He was convinced he was surrounded by superior numbers. The Finns seemed to be everywhere, hitting him with sniper attacks, five-minute mortar barrages and nighttime ski raids that kept his men awake and exhausted. Every time a Finnish sniper fired a bullet, panic-stricken Soviets would fire everything they had for as long as 15 minutes, causing no casualties but wasting ammunition. The Soviets called the Finnish snipers “cuckoos” for their treetop perches.

The Soviets were shocked by this situation. Two of their divisions were being slaughtered in the Finnish wilderness, and there seemed no way to get them out. The 44th had plenty of vehicles but no skis.

Now Siilasvuo’s men moved to methodically cut up the “mottis,” working to kill maximum numbers of Russians at minimum cost to themselves.

Vinogradov realized that his division was doomed. On January 4, he sent a message to 9th Army requesting discretion to act on his own initiative. The request was refused. But on January 6, after a further exchange of messages, Vinogradov was allowed to make a “tactical withdrawal.”

The division did not withdraw. Vinogradov gave his men an “every man for himself” order, and his men began fleeing across the forests and through the snow in little, brown-uniformed clumps.

But by then the 44th Division was almost destroyed. The Finns harried the fleeing men over the border, taking 1,000 prisoners while 700 Russians made it back to the Soviet Union, most of them the division’s Politruks. The political officers showed little courage; they tore off their insignia as they ran away.

The rest of the 44th Motorized Division’s 17,000 men died or fell prisoner to the advancing Finns.

As the 44th Division disintegrated, the Finns took possession of the Suomussalmi battlefield and vast amounts of abandoned equipment and men. They found the expected: 43 tanks, 270 other vehicles—trucks, tractors, prime movers—in various states of disrepair and destruction, along with 27,500 stiff Russian bodies from the 44th, the 163rd, and supporting commands. “The wolves will eat well this winter,” a Finnish officer said laconically.

The useful booty included four dozen artillery pieces, 600 working rifles, 300 functioning machine guns, a few mortars and tanks, and a collection of armored cars and trucks.

The Finns also found the unexpected: dozens of plaited leather whips sewn with ball bearings used by Politruks to “encourage” their men.

There were also hundreds of prisoners to care for, all undernourished, unfit, and many middle-aged conscripts, some of whom had no idea where they were. Some believed they were on the outskirts of Helsinki. Covered with body lice, they were terrified that they would be shot after horrific torture.

The Finns assured their captives such was not the case and deloused and reclothed their prisoners quickly. The Finns shot newsreel footage of their dirty uniforms being burned for propaganda purposes and shared hot food with the Soviets. The prisoners were astonished. They had assumed that the Finns were starving and whipped under a Fascist tyranny.

The Finns shot more newsreel footage of the scrawny and pathetic prisoners, particularly those with bad teeth, passing them out to reporters at the Hotel Kemp bar. The Finns suggested that the Soviets were sending “cannon fodder” into these battles to rid the Soviet Union its “undesirable elements.”

The Finns also fired artillery shells filled with lurid photographs of dead Soviet troops at the Russian front lines bearing a simple slogan “Belaya Smert,” meaning “White Death.”

The Finns also counted their own losses: 900 dead and 1,770 wounded.

The victory was classic and complete. Two Soviet divisions had been wiped off the map, utterly destroyed, in a miniature Cannae, by a far smaller and poorly equipped force. Only in mobility, leadership, and morale were the Finns superior to the Soviets. Once the Finnish troops cut the Soviets off from their supplies, denied them hot meals, and rendered them immobile, they had no chance. It was one of the great victories of military history and a legendary battle.

Such thoughts probably did not enter into Vinogradov’s head as he fled the battlefield, reaching Vazhenvaara in a commandeered T-26 tank. The Director General of the Red Army Political Directorate, Lev Mekhlis, was sent to investigate how the 44th Motorized Division and 163rd Rifle Divisions were slaughtered. The 163rd’s commander, Zelentsov, was not around to account for himself, but Vinogradov was certainly available, and Mekhlin placed Vinogradov and his commissar, Gusev, under arrest.

The Soviet GRU and the Army held an investigation and summary court-martial, which ordered Vinogradov and Gusev shot before the 700 survivors of the 44th Motorized Division who had made it back to Soviet lines. Among them was Akhmedov’s old pal Nikolayev, who “had become a physical and mental wreck. He cried steadily, babbled incoherently, shot blindly at anybody, and was soon sent to an asylum,’ Akhmedov said later.

Also shot a month later was 9th Army’s Ermolaev, whose “edited message” had helped condemn the 44th Division to its fate.

For Vinogradov, the stated court-martial offense of record was “the irrecoverable loss of 55 field kitchens.”

Author David Lippmann has contributed to WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in New Jersey.

I am 80 years old now and was a Marine Security Guard at our embassy in Helsinki from November 1966 to December 1967 and got to know a lot of Finns. They are wonderful people-full of life and VERY patriotic. Their army was and still is an extremely well-trained armed force. They still have mandatory military service and field a first class armed force. When I was in Helsinki, our maid, Paula, had been a sniper in Rovaniemi when she was just a teenager and her husband, Leo, was a LtCol in the Finnish army. The Finns are a proud, well educated, and tough people. I admire them and feel fortunate that I was able to meet and socialize with them.