By Flint Whitlock

On Tuesday, May 8, 1945, a strange sound was heard across all of Europe—the sound of silence. It was as if someone had suddenly flipped the war switch to “Off.”

No more ear-splitting explosions. No more cracking of bullets. No more wailing of air-raid sirens. No more moans of the wounded and dying. Just beautiful, serene silence.

The silence did not last long. It was quickly replaced by other sounds: the ringing of church bells across Europe, Great Britain, Canada, the U.S.S.R., and the United States. The voices of choirs. The prayers of thanksgiving by congregations. The cheers of drunken revelers, the sobs of people who had lost everything.

The European phase of World War II—a war that had devastated thousands of communities and cost the lives of tens of millions of people—was at last over.

The man who had started it—Adolf Hitler—had killed himself and was then incinerated by his minions outside a Berlin bunker. Hitler’s closest followers also had taken their own lives or had scattered like rats fleeing a burning building.

Another man—the man who had done much to bring about the end of Hitler’s Third Reich—was himself also dead. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the American president and architect of victory, had died just 26 days earlier of a cerebral hemorrhage in Warm Springs, Georgia.

Much of Europe—especially German cities—lay in ruins. Dazed Germans wandered through the rubble of their bomb-blasted streets, wondering what had hit them, wondering why they had blindly followed their leader into total ruin.

The infrastructure of German civilization was no more. Millions of still-standing buildings were unfit for habitation, their roofs and windows gone. Water lines had been shattered, sanitation services had been destroyed. Hospitals were gutted. Food and fuel were scarce or non-existent. Trains had ceased to run. Government had collapsed. Corpses piled up with no one to bury them. It was like a scene out of the biblical apocalypse.

How had this moment come about?

In early 1945, the Third Reich was reeling. American, British, Canadian, Polish, and Free French armies were closing in on Hitler’s empire from the West, while Joseph Stalin’s Red Army was bulldozing its way through German opposition in the East. In Italy, German armies were fighting a desperate retreat northward toward the Alps.

Despite the Germans’ best attempts to prevent the Western Allies from crossing the Rhine River, Germany’s last formidable natural defense, on March 7 elements of the U.S. 9th Armored Division found an intact bridge at Remagen and crossed to the eastern bank. Thousands of American G.I.s were soon plunging into the heart of Germany.

The Remagen crossing was followed on March 23 by Operation Plunder, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group’s crossing of the northern Rhine. But it was upstaged the next day when the Americans launched Operation Varsity, the largest airborne assault of the war. Over 17,000 paratroopers and glider forces of the Maj. Gen. William M. “Bud” Miley’s U.S. 17th and British 6th Airborne Divisions landed east of the Rhine in the vicinity of Wesel, north of the Duisburg-Essen-Düsseldorf industrial area.

Varsity was the responsibility of the U.S. XVIII Corps under Maj. Gen. Matthew Ridgway, who had commanded the 82nd Airborne Division during Operation Overlord, the Normandy invasion, in June 1944. A new transport plane, the C-46 Commando, would see its first major combat test during Varsity. Capable of carrying twice as many paratroopers (36) as the C-47 Dakota (18), the C-46 was faster and had doors on both sides of the fuselage, allowing troops to exit the aircraft more quickly than they could from the C-47.

Unlike the chaotic pre-dawn drops in Normandy in the early hours of Overlord, the Varsity aerial assault would take place in broad daylight. The first planes carrying the 17th Airborne began taking off from their Paris bases shortly after 7 AM; it took two hours before the last of the planes were aloft. A total of 9,387 American paratroopers and glider-borne soldiers were combined with over 8,000 British airborne soldiers in 72 C-46s, 836 C-47s, and 906 CG-4A gliders. The aerial armada was escorted by nearly 1,000 Allied fighters.

The first aircraft carrying Miley’s men reached their drop zones shortly before 10 AM and encountered heavy smoke and scattered anti-aircraft fire. But it didn’t take long for the parachutists of the 17th Airborne’s 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment to land and begin destroying enemy opposition.

As more and more paratroopers and glider infantrymen arrived, more and more German defenders of the 84th Infantry Division were either killed or captured. But the victory came at a cost, with scores of Americans killed when they ran into tough nests of the enemy.

Other casualties occurred when the C-46s unexpectedly burst into flames. The C-46 had no self-sealing fuel tanks, and when German 20mm incendiary antiaircraft rounds punctured them, they sent flaming fuel pouring from the wing tanks and onto the fuselage. Nineteen of the 72 C-46s were lost, with 14 falling like flaming meteorites, some with paratroopers on board; another 38 were severely damaged.

The first contingent of Waco CG-4A combat gliders began landing around 10:30 AM. Their arrival, too, was not without incident; 12 of the 295 tow aircraft were shot down and 14 more were forced to make emergency landings; 126 others sustained heavy damage. Six of the Wacos were also blasted out of the sky. Additional gliders landed by noon, followed by an aerial re-supply. Fierce skirmishes ensued, with the Yanks winning most of them.

The U.S. Army’s official history notes that the cost to the 17th Airborne Division alone during the first day’s operations was 159 killed, 522 wounded, and 840 missing (although 600 of the missing would subsequently turn up to fight again). The IX Troop Carrier Command alone lost another 41 killed, 153 wounded, and 163 missing. Fifty gliders and 44 transport aircraft were destroyed, another 332 transport planes were damaged, and only a few of the gliders were salvageable. British losses among the 6th Airborne Division were even heavier, especially in the number of killed.

At 3 PM on March 24, patrols from the British 1st Commando Brigade that had participated in Operation Plunder marched out of Wesel and linked up with elements of the 17th Airborne. In the days following March 24, XVIII Airborne Corps consolidated and expanded its sector and prepared for the drive east. The corps would soon be attached to Lt. Gen. William Simpson’s U.S. Ninth Army and General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group, to take part in the encirclement of the Ruhr, one of the last major operations in western Germany.

Churchill had wanted the British and Americans to reach Berlin ahead of the Soviets, but General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Western Allies’ supreme commander, wasn’t sure that was such a great idea. On March 30, 1945, Ike sent a cable to his boss, General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army Chief of Staff, that read in part, “May I point out that Berlin is no longer a particularly important objective. Its usefulness to the German has been largely destroyed and even his government is preparing to move to another area.”

Ike asked the advice of Bradley as to what the cost in casualties would be in taking Berlin. One hundred thousand killed and wounded was Bradley’s estimate. Ike decided to let the “honor” of taking the capital go to the Soviets. After all, at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the “Big Three” (Roosevelt, Churchill, and Stalin) had already decided that Berlin would be in the Soviet zone of occupation in a divided-up postwar Germany; Eisenhower saw no need for thousands of American boys to die for a city that would ultimately wind up in Soviet hands.

Churchill, of course, was furious and accused Eisenhower of overstepping his authority, but the ailing Roosevelt refused to countermand Ike’s decision.

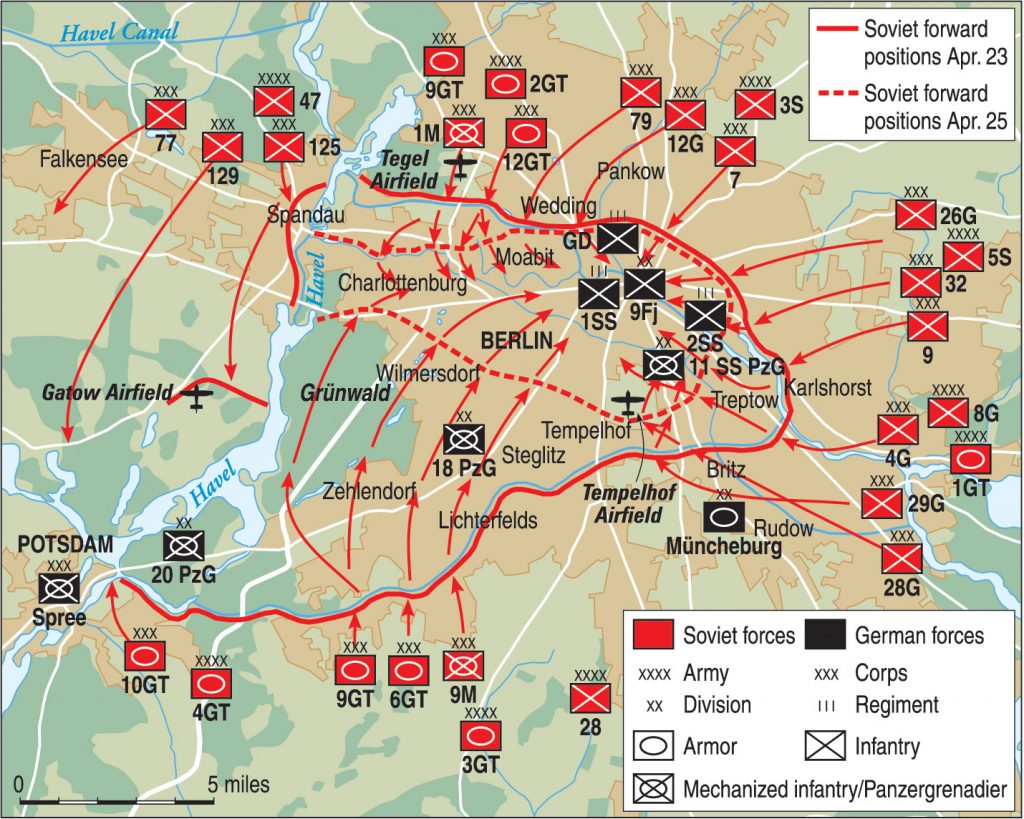

The Soviets were ready to claim their prize. Tasked with taking Berlin were two “fronts”—the Red Army equivalent of an army group—Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s First Belorussian Front and Marshal Ivan Konev’s First Ukrainian Front.

With a combined force of over 2.5 million men (including nearly 80,000 Poles who were fighting on the side of the Red Army), 7,500 warplanes, 6,250 tanks, 41,6000 artillery pieces, 45,000 mortars, and truck-mounted Katyusha rocket launchers, the Soviet plan called for the destruction of the German Army Group Vistula and Army Group Center that were guarding the eastern approaches to the capital. Konev’s army group would strike south of Berlin and then wheel to the north to encircle the city while Zhukov’s Belorussian Front would slam due west from Poland into Berlin.

The massive assault, larger than anything the British and American had ever thrown at the Germans, began on April 15. Zhukov’s forces ran into stubborn opposition by the German Ninth Army 56 miles to the east of Berlin at a place called Seelow Heights. Here the savage fighting went on for a period of four days. Over 700 Red Army tanks were destroyed, along with some 30,000 attackers; the outnumbered Germans had over 10,000 men killed.

With Zhukov’s men unable to break through, he was ordered to bypass Seelow Heights and circle Berlin to the north while Konev’s formations were ordered to hit Berlin from the south.

As the Soviets advanced, towns and villages were set afire, just as the rampaging German armies had done during Barbarossa. German civilians caught in their path began committing suicide to avoid being taken by the avenging Soviets.

The British Broadcasting Company (BBC) reported, “Konev’s forces to the south of Berlin have taken more than 10,000 prisoners in the past four days. They also claim to have captured 96 aircraft and more than 150 tanks and self-propelled guns. Marshal Zhukov’s troops, heading from the north and east, claim to have taken more than 13,000 prisoners, 60 aircraft, and more than 100 tanks and self-propelled guns.”

Adding to the destruction were five raids by RAF bombers. It seemed that nothing could survive such an onslaught. And yet pockets of German troops, scattered here and there, were supplemented with pitiful handfuls of old men and boys known as the Volksturm—the German home defense militia—who set up barricades, received rudimentary instructions on how to fire rifles and anti-tank panzerfausts, and prepared to defend their city or die trying.

On April 20—Hitler’s 56th birthday—with Berlin now effectively surrounded, the Red Army unleashed the heaviest artillery bombardment of the war. As one historian noted, “The weight of ordnance delivered by Soviet artillery during the battle was greater than the total tonnage dropped by Western Allied bombers on the city.”

In the midst of the siege, a subdued birthday celebration for Adolf Hitler was held in the dank concrete Führerbunker below the Chancellery on Wilhelmstrasse. In attendance were some of Nazi Germany’s elite: Joachim von Ribbentrop, Alfred Jodl, Hermann Göring, Heinrich Himmler, Joseph Goebbels, plus an assortment of ministers and staff members.

After presenting birthday wishes to Hitler, ministers, generals, and staff officers said their farewells and began to slip away, hoping to depart the flaming, crumbling city before all avenues of escape were cut off. Göring quietly snuck out of Berlin and headed south to his vacation home at the Nazi enclave at Berchtesgaden. But Martin Bormann, head of the Nazi Party Chancellery and Hitler’s private secretary, noticed Göring’s absence and suspected a coup was brewing.

One of Germany’s ace fighter pilots in World War I (18 Allied planes shot down), Göring had helped Hitler come to power and had been rewarded with high offices—commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, president of the Reichstag, and head of the Gestapo.

Bormann, who despised Göring, was aware of the secret decree that Hitler had issued back on June 29, 1941, that rewarded Göring’s loyalty with the pledge that, should Hitler be killed or captured, Göring would succeed him as head of government.

Luftwaffe General Karl Koller, chief of staff of the German Air Force, had also been in the Führerbunker on April 20, where he was privately told by Jodl of Hitler’s plans to commit suicide. Aware of Göring’s escape from Berlin,

Koller was somehow able to fly out of beleaguered Berlin at 3:30 AM on April 23 and reached Göring at the Obersalzberg in Berchtesgaden to personally give him the news of Hitler’s impending suicide.

Göring then sent Hitler a telegram stating, “My Führer: General Koller today gave me a briefing on the basis of communications given to him by Colonel General Jodl…according to which you had referred certain decisions to me and emphasized that I, in case negotiations would become necessary, would be in an better position than you in Berlin. These views were so surprising and serious to me that I felt obligated to assume, in case by 10 o’clock tonight no answer is forthcoming, that you have lost your freedom of action.

“I shall then view the conditions of your decree [of June 29, 1941] as fulfilled and take action for the well being of Nation and Fatherland. You know what I feel for you in this gravest hour of my life and I cannot express this in words. May God protect you and speed you quickly here in spite of all.”

He signed the telegram, “Your faithful Hermann Göring.”

But Bormann intercepted the telegram and warned Hitler that the “faithful Göring” was about to overthrow the government. Outraged, Hitler sent a reply to Göring, telling him that the 1941 decree was rescinded and that he would be arrested for high treason if he did not immediately resign all his offices. Bormann directed SS troops to find Göring and place him under house arrest at the Obersalzberg.

The SS found Göring, but with his persuasive eloquence and exalted rank, managed to convince his would-be captors to not only let him go but to escort him and his entourage to his family castle at Mauterndorf, near Salzburg, Austria, in preparation for a meeting with the Americans.

Hitler next sent a message to Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander in chief of what was left of the German Navy, telling him that he was to become his successor upon his, Hitler’s, death.

Meanwhile, SS chieftain and Deputy Führer Heinrich Himmler, who had always been as faithful as a lapdog to his führer, had been secretly working behind Hitler’s back, trying to arrange for a separate peace with the Western powers and releasing a few hundred Jews from the concentration camps in a futile, cynical attempt to cleanse his odious record as a mass murderer. After slipping out of Berlin, he made his way to Dönitz’s headquarters in northern Germany, hoping to effect a meeting with Eisenhower or Montgomery. But Dönitz was having none of it.

Now in a panic, Himmler tried to disguise himself by shaving off his moustache, putting on an eye patch, and carrying the identity papers of Heinrich Hitzinger, an enlisted man in the Secret Field Police. He was soon taken into custody by the British and gave them his true identity. (He would avoid justice on May 23, 1945, by taking his own life with a cyanide capsule while being interrogated by the British in Lüneburg.)

Meanwhile, the battles outside the Führerbunker were continuing to a thundering conclusion. Berlin had become a shrinking killing zone, the bull’s eye for every Soviet gun, tank, aircraft, and rifle, but still some citizens and a few hard-core military units fought on. Young boys and old men stood at hastily erected barricades with their panzerfausts and a few measly rounds of rifle ammunition, willing to die for a cause that had lost whatever meaning it might once have had.

During this period, Hitler received an unexpected visitor: aviatrix, test pilot, and ardent Nazi Hanna Reitsch. She had flown many of Germany’s advanced aircraft (including a manned version of the jet-powered V1 flying bomb) and now she had braved enemy fire to land her small plane on a Berlin boulevard with an offer to fly Hitler to safety. He was touched by her brave gesture but felt compelled to decline the offer. However, if she could rally the Luftwaffe to bomb the advancing Russians, he would be forever grateful. That was probably not possible, but she did airlift Luftwaffe General Robert Ritter von Greim (who had been appointed head of the Luftwaffe after Göring’s ouster), out of besieged Berlin. (He would commit suicide on May 24, 1945.)

Deep in his bunker, Hitler continued living in a delusional, fantasy world. Thinking that he still had vast numbers of troops and divisions at his disposal, he began issuing orders to move various units about as though they were chess pieces; his advisors could not bear to tell him that many of the units had ceased to exist or had no transportation with which to make such moves—and no arms or ammunition, either.

At one point—April 22—Hitler went berserk. After learning that a counterattack he had ordered had not taken place, he flew into a frenzy the likes of which no one present had ever seen. For hour upon hour the Führer raged, his fists banging on a table, his face turned purple with anger over the cowardice of the German people and the treachery of his once-loyal followers who had abandoned him and Germany in an attempt to save themselves.

Once his rage was spent, a sweating, panting Hitler slumped into a chair and seemed resigned to his fate; he directed Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels to broadcast a radio message announcing that Berlin would be defended to the end and that he, as their leader, would never surrender, and that anyone who showed cowardice, hoisted a white flag, or attempted sabotage would be treated as a traitor and shot.

Even at this eleventh hour, Joseph Goebbels still clung to the hope that Britain and America would come to their senses and realize that the real enemy was the Soviet Union, not Nazi Germany. There was still time, he believed, for the Western Allies to join with the Germans to throw back the Bolshevik hordes and save civilization. But, like Hitler’s illusions of imaginary German divisions coming to his aid, it was nothing but a pipe dream.

While this drama played out below ground, Red Army troops were in the streets of Berlin, battling for every block and rooting out determined defenders from cellars. At the Reichstag, the German Parliament building, German troops had turned its burned and blasted interior into a fortress, and sent many attacking Soviets to their deaths before they were themselves killed.

To the west of Berlin, the Americans and British pushed ever eastward until, on April 25, Soviet and American troops shook hands on a small bridge over the Elbe River near the town of Torgau, 85 miles south of Berlin.

By that time, the Nazi concentration camp known as Buchenwald, high on a hill overlooking Weimar, had been discovered by American troops, and the British had overrun Bergen-Belsen; the crimes of the Nazis had been laid bare for all the world to see. (Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland had been liberated by the Soviets in January 1945, but the horrors encountered were either played down in the media or widely disbelieved in the West.)

In the pre-dawn hours of April 29, Hitler took a bride—his long-suffering mistress Eva Braun. A city official was found to perform the brief civil ceremony followed by what war correspondent William L. Shirer called “a macabre wedding breakfast.” Following the ceremony and breakfast, Hitler dictated his last will and testament to one of his faithful secretaries. The testament formally expelled the traitorous Göring from the Nazi Party and named Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz to be the new head of the nation.

Hitler’s End

The Third Reich’s 12-year life span was quickly coming to an end. Albert Speer, Germany’s Minister of Armaments, called upon his Führer, burrowed in his bombproof bunker. Speer wrote in his memoirs, “I was led into Hitler’s room in the bunker. In his welcome there was no sign of the warmth with which he had responded a few weeks before to my vow of loyalty. He showed no emotion at all. Once again I had the feeling that he was empty, burned out, lifeless….

“Abruptly, Hitler asked me, ‘What do you think? Should I stay here or fly to Berchtesgaden? [Chief of the Operations Staff of the Armed Forces High Command—Oberkommando der Wehrmacht—Alfred] Jodl has told me that tomorrow is the last chance for that.’

“Spontaneously, I advised him to stay in Berlin. What would he do at Obersalzberg? With Berlin gone, the war would be over in any case. I said. ‘It seems to me better, if it must be, that you end your life here in the capital as the Führer rather than at your weekend house [in Bavaria].’”

Hitler replied that he had already decided to remain in Berlin but just wanted to hear Speer’s advice. “I shall not fight personally,” Hitler told him. “There is always the danger that I would only be wounded and fall into the hands of the Russians alive. I don’t want my enemies to disgrace my body, either.”

He then told Speer of his plans to kill his dog Blondi, his new bride Eva Braun, and then himself. “I felt as if I had been talking with a man already departed,” Speer said. “The atmosphere grew increasingly uncanny; the tragedy was approaching its end.”

The end for Mr. and Mrs. Hitler came on April 30, when Eva took poison and he bit down on a cyanide capsule and simultaneously blew his brains out with a pistol. Their bodies were carried upstairs and into the small garden where an SS man cremated them.

Joseph Goebbels and his wife Magda had decided that they could not live in a world without Hitler, and were terrified by the thought of falling into Russian hands. Once Hitler was dead, the Goebbels took their own lives—along with those of their six children—in the Chancellery bunker. Their bodies were carried outside, soaked with gasoline, and set alight; the Russians found the charred corpses—along with Hitler’s—when they reached the Chancellery.

Once the city fell on May 2, many Red Army troops engaged in an orgy of lawlessness—raping, murdering, and pillaging. (See WWII Quarterly, Spring 2012.) Starvation among the civilians was rampant, and over a million people were without shelter.

A Life magazine reporter described the scene: “In the stench of the subways and the spring bloom of the Tiergarten [zoo], the Germans tried to defend their capital, Berlin, a city desperate in the presence of death. Those German soldiers who were not killed by Russian bullets burned to a crisp in the gutted buildings or drowned in the canals. Others died of thirst when the city’s water supply was cut off. With the guns of SS men at their backs, Germans battled in a senseless, suicidal last stand. But the Russians, at the end of their bloody pilgrimage from Stalingrad, fought even harder. In the 12-day battle, the Russians killed almost 150,000 Germans, captured 200,000….

“There are no cities left in Germany. Aachen, Cologne, Bonn, Koblenz, Würzburg, Frankfurt, Mainz—all gone in one sweeping reach of destruction.”

Formal Surrender

There were a series of surrender ceremonies as German divisions, corps, and army groups gave themselves up to whatever Allied unit was closest. And, whenever possible, German units capitulated to American and British units, even driving or marching great distances in order to avoid ending up in the hands of the Red Army. (And with good reason; the Soviets eventually took over a million German soldiers prisoner—only a small percentage would return home alive after the war.) In many cases, American companies and platoons received the surrender of battalions and regiments that were still armed but without the will to continue fighting.

The German army forces in Italy, commanded by Heinrich von Vietinghoff, officially surrendered on May 2, 1945, inside a room in the sprawling Royal Palace at Caserta, 10 miles north of Naples. (In early March, SS General Karl Wolff, at Vietinghoff’s direction, had made contact with Allen Dulles, an official of the Office of Strategic Services [OSS] in Switzerland, in hopes of negotiating an end to the fighting in Italy.)

On May 3, British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery demanded the surrender of all German forces in northern Germany at his field headquarters on the Lüneburg Heath. Monty was unbending in his three unconditional-surrender demands to German Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg, commander of the German navy, General Eberhard Kinzel, chief of staff to Field Marshal Ernst Busch, and two other officers.

The Germans said, “We come from Field Marshal Busch to ask you to accept the surrender of three German armies [Third Panzer Army, Twelfth Army, and Twenty-first Army] which now are withdrawing in front of the Russians in the Mecklenberg area. We are very anxious about the condition of German civilians who are fleeing as the German armies retreat in the path of the Russian advance. We want you to accept the surrender of these three armies.”

Montgomery was dismissive. “No,” he said. “Certainly not. Those German armies are fighting the Russians. Therefore, if they surrender to anyone, it must be to the forces of the Soviet Union. They have nothing to do with me. I have nothing to do with the happenings on my eastern front.”

Monty then told the Germans bluntly: “You must understand three things: Firstly, you must surrender to me unconditionally all the German forces in Holland, Friesen, and the Frisian Islands and Helgoland and all other islands in Schleswig-Holstein and in Denmark.

“Secondly, when you have done that, I am prepared to discuss with you the implications of your surrender: how we will dispose of those surrendered troops, how we will occupy the surrendered territory, how we will deal with the civilians, and so forth.

“And my third point: If you do not agree to Point One, the surrender, then I will go on with the war and I will be delighted to do so and am ready. All your soldiers will be killed. These are the three points—there is no alternative—one, two, three, finished!”

After the delegation took the terms back to Dönitz, he approved them on May 4.

Another surrender took place in Innsbruck, Austria, on the same day when a delegation from the Nineteenth Army surrendered to the Americans from the 44th Infantry Division. On May 5, Army Group G in southern Germany officially surrendered to the Americans in a ceremony 12 miles east of Munich.

Two days later, German Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, the head of the Third Reich after Hitler’s suicide, declared an unconditional surrender against the Allied forces and the Soviet Union. In his SHAEF headquarters in a non-descript, red-brick industrial college building in Reims, France—90 miles northeast of Paris—an exhausted Eisenhower paced and smoked. He had decided to send his deputy, Walter Bedell Smith, to sign for him but to not attend the signing ceremony himself, a way of showing the German delegation that they were not worthy of his presence.

A few hours before dawn on May 7, Admiral Dönitz and Colonel-General Alfred Jodl signed the instruments of surrender; Smith signed for Ike. (The building and room in which the signing ceremony took place has been preserved as a museum.)

Eisenhower waited for Smith to bring in the signed documents. As Ike’s biographer Stephen E. Ambrose wrote, “Eisenhower knew that he should feel elated, triumphant, joyful, but all he really felt was dead beat. He had hardly slept in three days; it was the middle of the night; he just wanted to get it over with.”

On May 7, elements of Maj. Gen. John Dahlquist’s 36th Infantry Division drove from the division’s base at Kitzbühel, Austria, and intercepted a convoy near Bruck, Austria, that included Göring, his wife Emmy, daughter Edda, sister-in-law, household servants, and military aides. The Reichsmarschall and his entourage gave up without a fight. (Göring would be tried at Nuremberg as a war criminal, found guilty, and sentenced to death, but cheated the hangman on October 15, 1946, by taking poison that had been smuggled into his cell.)

Many of Hitler’s other henchmen sought to flee the apocalypse. Martin Bormann, the second most powerful man in the Nazi Party, tried to escape the besieged city on May 2, but had apparently died during a Soviet bombardment. (His skeletal remains were uncovered at a construction site in West Berlin in December 1972. Forensics experts established that the remains were Bormann’s; DNA testing later confirmed that finding.)

Others whom the long arm of justice was about to corral headed out of Germany with the help of such pro-Nazi escape groups as ODESSA and sought refuge in other countries. Adolf Eichmann, one of the architects of the “final solution,” was tracked down in Argentina and kidnapped by Israeli Mossad agents, put on trial in Israel, and executed by hanging in 1962. Thousands more Nazis, however, managed to escape to various parts of South America and were never brought to justice.

Dr. Josef Mengele, Auschwitz’s “angel of death,” had also fled to South America, lived as a free but hunted man for 34 years, and died of an apparent stroke while swimming at a Brazilian beach in February 1979.

Rumor of a Redoubt

There remained the persistent rumor of a German National Redoubt in the mountains of extreme southeast Bavaria where it was feared that Hitler, his closest associates, and a staunch guard of SS men would hold out to the bitter end. So, in one of the last major Allied bombing missions of the war, the RAF on April 25 plastered much of the Nazis’ mountain enclave at Berchtesgaden into unrecognizable rubble.

Eisenhower wrote, “That stronghold and symbol of Nazi arrogance was thoroughly pounded with high explosives. The bombing took place when we still thought the Nazis might attempt to establish themselves in their National Redoubt, with Berchtesgaden as the capital. The photo reconnaissance units brought back pictures that showed our bombers had reduced the place to a shambles; from them we derived a gleeful and understandable satisfaction.”

On May 4, elements of three Allied units were driving hard through the Bavarian Alps toward Berchtesgaden: the U.S. 3rd Infantry Division, 101st Airborne Division, and the French 2nd Armored Division. Each wanted the honor of capturing this alpine retreat where Hitler and many of cronies—Göring, Himmler, Bormann, and others—had established homes as places to get away from the stresses of the war and life in Berlin and to entertain and impress such important guests as Benito Mussolini, French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier, Neville Chamberlain, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor.

No one knew if the area would be bristling with fanatical SS troops vowing to defend their Führer in a duel to death or if it would be a quiet, abandoned place. Luckily, there were no fanatical SS troops or anyone else wanting to make a final stand.

The mission of taking the Obersalzburg had been assigned to the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne, but elements of the 3rd Infantry Division got there first, effectively shutting out Le Clerc’s French tank troops. Looting began immediately within the rubble of the bombed-out buildings; even Göring’s huge Mercedes-Benz 540K limousine was appropriated by the 507th’s Colonel Robert Sink.

Also found was Göring’s personal train, loaded with priceless paintings that the Nazis had stolen over the years from across Europe for his personal art collection.

Worldwide Celebrations

There would be time for retribution and time to mourn, but now, on May 8, it was time to celebrate what came to be called V-E Day—Victory in Europe Day. With war in the European Theater of Operations at last concluded, nations across the world celebrated the defeat of Germany with a joyous spontaneity not seen before or since.

Celebrations in New York City were joyfully frenzied. In Times Square, two million people cheered, sang, kissed strangers, and danced a conga line through the paper-strewn streets. Life magazine said, “Wild celebrations were whitened by snowstorms of paper cascading from buildings in Times Square, Wall Street, and Rockefeller Center.

“Ships in the rivers let go with their sirens. Workers in the garment center threw bales of rayons, silks, and woolens into the streets to drape passing cars with bright-colored cloth. Then the workers swarmed out of their shops, singing and dancing, drinking whiskey out of bottles, wading in their own weird confetti.”Similar scenes played out across the country.

The Los Angeles Times ran an editorial that read, in part: “In our rejoicing over this complete victory, approximately 11 months after our landing in Normandy, the people must not forget that there is another foe to deal with. Japan, though she is evidently beaten, shows no sign of giving in. Her armies must be defeated as utterly as those of Germany. That is now the task before the United States and it allies. On to victory in the Pacific!”

The San Francisco Chronicle’s columnist Royce Brier detected relief but no overwhelming joy in his city by the bay. He wrote, “There has been a quizzical spirit so far as one could feel it in America, in San Francisco, these last days, and a reluctance to go off the deep end even with such a burden as the European physical menace lifted. The ogre is dead, and yet you have not the heart to rejoice.”

San Francisco would save its unbridled celebrations for V-J Day—Victory over Japan—in September, when the drunken celebrations would turn into the deadliest riots in the city’s history.

In London, crowds massed in Trafalgar Square and in front of the gates of Buckingham Palace, where King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, accompanied by Princess Elizabeth (soon to be queen), Princess Margaret, Prince Philip, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill, appeared on the balcony of the palace, smiling and waving to the cheering, flag-waving crowds.

The May 21, 1945, issue of Life magazine reported, “London went happily mad on V-E Day…. Londoners took to the streets to dance, sing, climb lampposts, overturn a few taxis, and drain the pubs of their small stocks. At one point Trafalgar Square was so packed that pigeons fluttered helplessly overhead, unable to find landing space.

Then, as David Brinkley wrote in his 1988 book, Washington Goes to War, at 8:30 PM on May 8, “the lights on the United States Capitol were lit. For the first time since December 9, 1941, the great white dome gleamed splendidly in the night sky.”

The new American president, Harry S. Truman, spoke to the nation by radio, expressing his sadness that President Roosevelt had not lived to see the victory that he had engineered, and reminded Americans that the Japanese foe was down but not yet out: “This is a solemn but glorious hour…. Our rejoicing is sobered and subdued by a supreme consciousness of the terrible price we have paid to rid the world of Hitler and his evil band. Let us not forget, my fellow Americans, the sorrow and the heartache which today abide in the homes of so many of our neighbors—neighbors whose most priceless possession has been rendered as a sacrifice to redeem our liberty.…

“If I could give you a single watchword for the coming months, that word is work—work and more work. We must work to finish the war. Our victory is only half won.”

Casualties

The casualty rolls in Europe were staggering, but no one knows for certain how many died or were injured. Best estimates say that four million German soldiers and two million German civilians died; 21-28 million Russians; 330,000 Italians; 200,000 French soldiers and 400,000 civilians; 6,000 Belgians; 10,000 Norwegians; three million Poles; 5,700 Luxembourgers; 147,000 Hungarian soldiers; half a million Greeks; 73,000 Romanians; 1.7 million Yugoslavs; 19,000 Bulgarians; 264,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers; and over 276,000 Americans (in Europe, North Africa, and the Mediterranean alone). Six million European Jews had been exterminated.

Soviet deaths in the siege of Berlin exceeded 81,000. A major Soviet war memorial, erected in 1945, was built from stonework taken from the destroyed Reich Chancellory. It is set in a landscaped garden at the Tiergarten near the Brandenburg Gate and is flanked by two Red Army ML-20 152mm artillery pieces and two T-34 tanks. Behind it is a military cemetery containing the graves of over 2,000 Red Army soldiers. The memorial is guarded night and day by Russian soldiers and is a daily reminder to Berliners of who the victors were. (Another, larger, memorial is at Treptower Park.)

The war in Europe was over, but one more foe still stood defiant and needed to be conquered: Japan.