By R. Douglas Nunes

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, the infamous “Desert Fox,” was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Army Group B on the Western Front and put in charge of strengthening the Normandy coastal defenses.

In the months leading up to the Allies’ D-Day invasion, Rommel ordered the construction of more bunkers and machine-gun emplacements, the laying of millions more land mines, and the installation of thousands more anti-landing-craft obstacles. Possible landing sites for gliders were either flooded or filled with upright posts known as “Rommel’s asparagus.” But it was not enough. The Allies came ashore, broke through the coastal defenses, and began pushing the Germans back.

On July 17, 1944, while traveling in his open-top staff car, Rommel was attacked by Allied warplanes and seriously wounded. Many stories have swirled around the identity of who actually deserves credit for the attack that put the former commander of the Afrika Korps hors de combat.

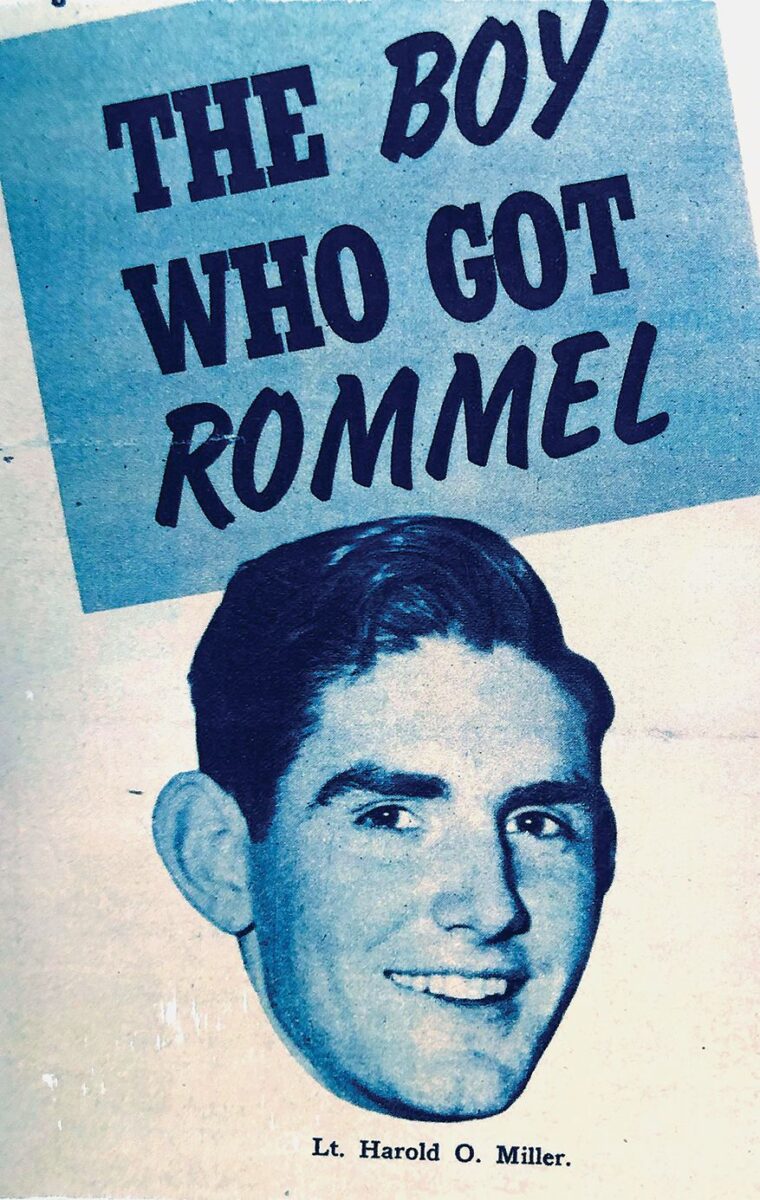

P-47 “Thunderbolt” pilot Harold O. “Hal” Miller—my father—was initially credited with shooting up Rommel’s car, becoming known locally as “the Boy Who Got Rommel.”

Born in 1924 in Galt, California, Miller grew up in Sonoma County, graduating from Santa Rosa High School in 1942. He enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Force at 18, and trained as a fighter pilot. While in flight training in Alabama, he married his hometown sweetheart, Peggy Degner.

Arriving in England, he was assigned to the 352nd Fighter Squadron of the 353rd Fighter Group, stationed at RAF Raydon near Ipswich, England. The youngest pilot in the squadron at 20, he flew his first combat mission May 3, 1944, flying escort for B-17 bombers that were hitting targets in Germany. Over the next few weeks, he and the 352nd engaged in strafing missions on enemy trains, truck convoys, ground troops, and battled German aircraft in the skies.

He flew two missions over the D-Day beaches in his P-47 “jug” nick-named “Sniffles” and flew often during the next few weeks. He was once forced to make a crash landing on Sword Beach, near Caen.

On July 24, Miller reported that he had fired on a German officer’s staff car; his gun camera confirmed that fact.

“I spotted the staff car coming down the road and I made a diving turn. When I got it in my sights within range, I let loose with all my guns. I was lucky and my first burst scored direct hits,” Miller would later recall.

“The fuel tank exploded and it burst into flames. It left a trail of blazing gasoline for about 200 yards and then swerved into a ditch. Then it bounced into a field and I watched it. I came back for another look to make sure it was a goner.”

But exactly who was in the staff car remained a matter of conjecture. On September 1, Army intelligence surmised that Miller’s target on July 24 was probably Rommel.

After just four months in Europe, Miller was credited with destroying six enemy aircraft, with another “probable” and two damaged, 56 locomotives and 109 truck convoys. He was considered an “ace”—having destroyed five or more aircraft—and was awarded the Air Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters and the Distinguished Flying Cross.

After flying 75 missions, Miller was rotated back to the States to serve as a flight instructor. He was given a ticker-tape parade in New York City and then went on a war-bond sales tour along with several Hollywood celebrities, including Bob Hope and Frances Langford.

Miller’s exploits were front-page news. The Santa Rosa Press-Democrat headline on November 29, 1944, proclaimed, “S.R. Flyer Hailed for Strafing Raid that Killed Gen. Rommel.” The sub-head read, “Lt. Harold Miller Tells Own Story As Secrecy Lifted.”

Unfortunately for Miller—in spite of news clippings to the contrary—he did not ultimately receive credit as the pilot who “got” Erwin Rommel.

Rommel was badly wounded in an aerial attack, but was not killed. He was hospitalized with serious head injuries and by August he was able to return to Germany to recover.

Instead of a hero’s death on the battlefield, Rommel was implicated in the July 20, 1944, plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler. Though there is no evidence Rommel was actively involved in the plot, Hitler ordered his death. Given the choice of committing suicide or being executed and having his family persecuted, he chose cyanide on October 14, 1944, and was given a state funeral with full military honors.

So who did shoot up Rommel’s car? Through extensive research, Reginald Byron, archivist at the Tangmere Military Aviation Museum in England, wrote in 2016: “The bare facts of the case, insofar as I have been able to establish some consensus about them from the sources I have seen, are that Rommel’s car was attacked south of Livarot on the N179 in the direction of Vimoutiers near the village of Ste. Foy de Montgommery sometime between 5 and 7:30 p.m. [on July 17]. The aircraft appear to have been Spitfires. The car was forced off the road and Rommel was thrown out of it, suffering serious head injuries.”

Byron has concluded through all the evidence he has been able to uncover that the pilots who attacked Rommel’s Horch staff car were most likely Charley Fox of the Canadian 412 Squadron and Ed Priser, an American flying for the RCAF.

Since 1944, at least eight claims of responsibility for shooting up Rommel’s car have been made, with that of Captain Ralph C. Jenkins of the 510th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, Ninth U.S. Air Force, being given the most credence. However, Byron’s research seems to be the most conclusive.

So it wasn’t my dad who killed the famous field marshal after all, but he enjoyed a brief moment spotlight. He left the Air Force in 1950 and worked as a Federal Civil Defense Manager for 35 years, before retiring to his 56-foot Morgan Catch in Florida and the Bahamas. He died in 2004.

How can you print this drivel? History knows he was forced to take cyanide to save his family from death.

As you suggest, perhaps all of our readers know Rommel was not killed in Normandy in 1944. And most likely know about Rommel’s wounding in an aerial attack on July 24. This is a story about the mystery of that event at the time it happened, an interesting footnote to a well-known fact. For more about Rommel, including his death as described by Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, you might find this story of interest:

https://warfarehistorynetwork.com/article/reassessing-rommel-anti-nazi-hero-or-opportunist/