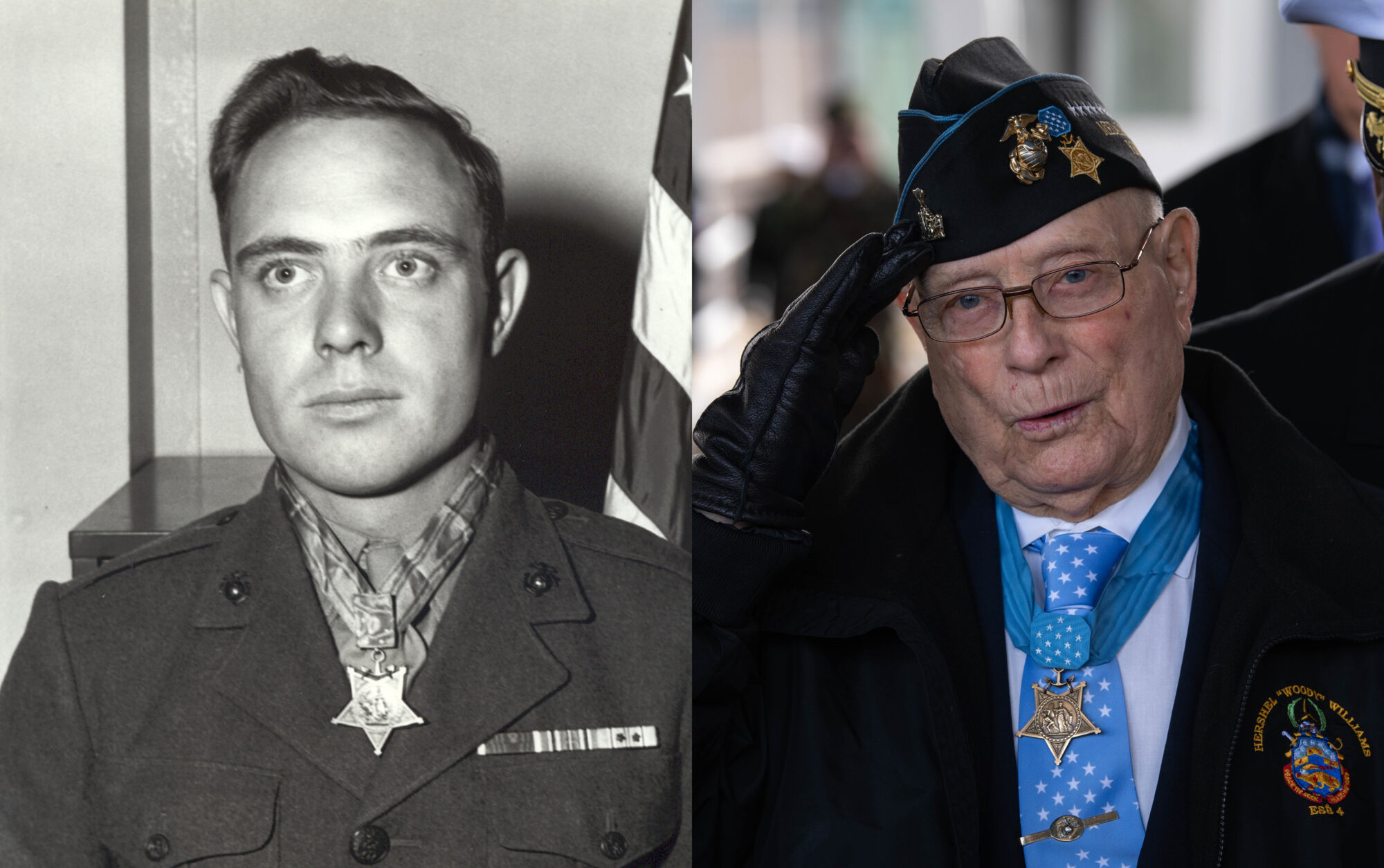

The citation made it plain. U.S. Marine Corps Demolition Sergeant Hershel W. “Woody” Williams had exhibited extraordinary courage during the bloody, protracted fight for the porkchop-shaped scrap of land in the Volcano Islands known as Iwo Jima. When the month-long fight for Iwo Jima was over, Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz remarked that the battle was one in which “uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

Williams was born prematurely in the town of Quiet Dell, West Virginia, and at 3.5 pounds wasn’t expected to live. Even then he defied the odds, growing up much of the time without his father, who died prematurely of a heart attack. Woody was attracted to the Marine Corps because of the dress blue uniform but was turned down for enlistment in 1942 because at five feet, six inches, he didn’t meet the minimum height. A year later, the height requirement had changed, and he was accepted into the Marine Corps Reserve.

By the time the 1st Battalion, 21st Marines landed on Iwo Jima, Williams had already taken part in the action on the island of Guam during the Marianas campaign. On February 21, 1945, he was 21 years old and found himself in the thick of the fighting.

During World War II, 473 U.S. service personnel received the Medal of Honor, and when Woody Williams died on June 29, 2022, he was the last of them. Williams was 98 years old, and after the war he had joined the Department of Veterans Affairs and worked for 33 years, helping others to deal with the effects of post traumatic stress disorder while coping with his own for many years. He once said, “For me, receiving the Medal of Honor was actually a lifesaver because it forced me to talk about the experiences that I had, which was therapy that I didn’t even know I was doing.”

Woody served 17 years in the Marine Corps Reserve and attained the rank of chief warrant officer 4. He experienced a renewal of his religious convictions in the 1960s and subsequently served as chaplain of the Congressional Medal of Honor Society for 35 years. In recognition of a life of service, the VA medical center in Huntington, West Virginia, was named in his honor in 2018. His story is an example of tremendous good being derived from horrific circumstances.

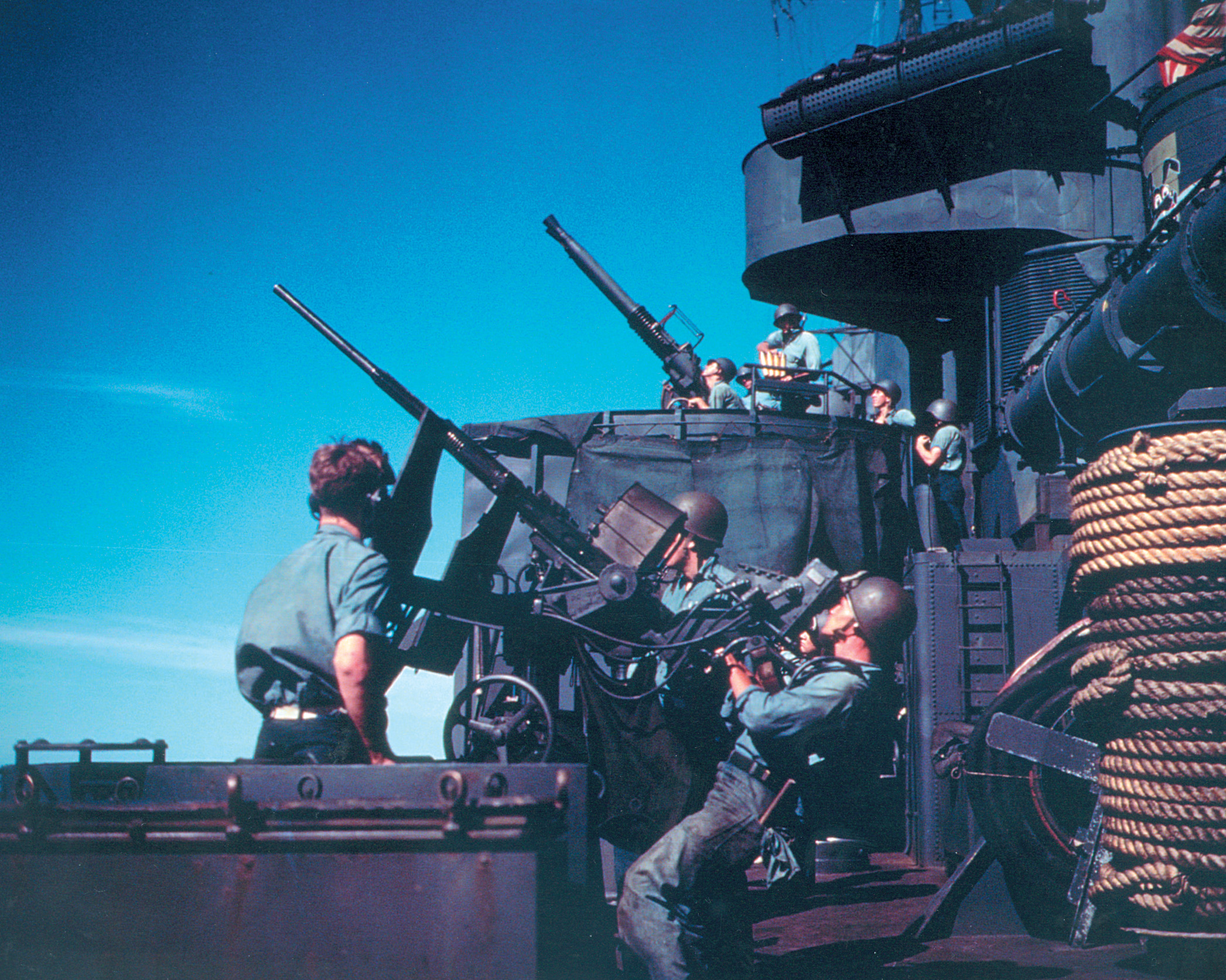

That day on Iwo Jima defined the course of Woody Williams’ life. He responded as tanks accompanying his unit were attempting to clear the way forward through a maze of enemy pillboxes and mines, wielding a flamethrower to destroy Japanese strongpoints on several occasions.

His citation reads in part: “…Williams daringly went forward alone to attempt the reduction of devastating machine-gun fire from the unyielding positions. Covered by only four riflemen, he fought desperately for four hours under terrific enemy small-arms fire and repeatedly returned to his own lines to prepare demolition charges and obtain serviced flame throwers, struggling back, frequently to the rear of hostile emplacements to wipe out one position after another. On one occasion, he daringly mounted a pillbox to insert the nozzle of his flame thrower through the air vent, kill the occupants and silence the gun; on another he grimly charged enemy riflemen who attempted to stop him with bayonets and destroyed them with a burst of flame from his weapon….”

Woody Williams, and the other Medal of Honor recipients from World War II, live on in the stories of their heroic exploits. Their bravery and sacrifice are enshrined, but Williams once told the Washington Post about the personal journey which followed that memorable day on Iwo Jima. “It’s one of those things you put in the recess of your mind,” he reasoned. “You were fulfilling an obligation that you swore to do, to defend your country. Anytime you take a life, there’s always some aftermath to that if you’ve got any heart at all.”

He did have a heart and spent the rest of his noble life helping others. Call it atonement if you wish; so be it. Compassion and care, byproducts of the Medal of Honor experience, are his lasting legacy.

—Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments