By Flint Whitlock

To bring soldiers swiftly and silently onto a battlefield, the U.S. Army decided to follow the German and British examples and build tactical gliders. But troubles galore plagued America’s glider manufacturing program from the very beginning.

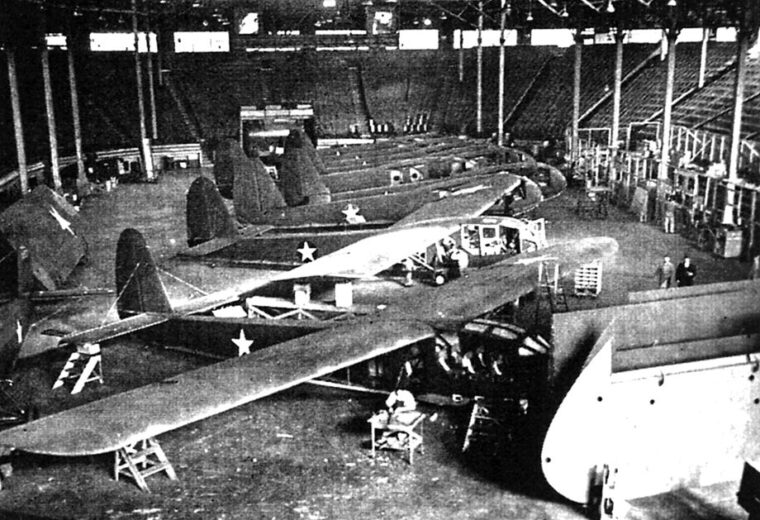

Sixteen companies were eventually contracted to produce the CG-4A glider—an American record for an aircraft having the most individual manufacturers. But, with almost the entire American manufacturing industry being awarded contracts to build an incredibly wide variety of military goods, finding enough companies with aircraft manufacturing experience was next to impossible.

Aircraft companies such as Boeing, Northrop, Grumman, Douglas, North American, Curtiss-Wright, Republic, Ryan, Taylorcraft, Aeronca, Piper, Beech, Consolidated, Vultee (Consolidated and Vultee would merge in March 1943 under the name Convair), and even Ford and General Motors were already up to their eyeballs in war-related work. The government, therefore, was forced to look elsewhere to find companies it hoped were capable of turning out large quantities of gliders.

The Waco CG-4A: America’s Tactical Glider

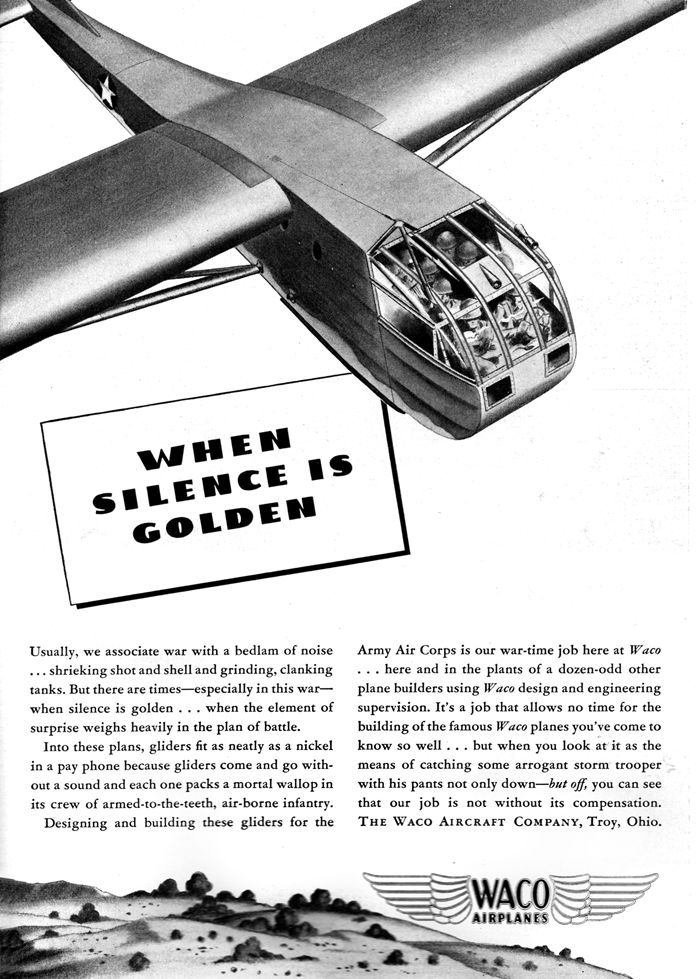

The winning design for the CG-4A (the CG stands for Cargo Glider) was submitted to the Army by the Waco (pronounced “wocko”) Aircraft Company of Troy, Ohio. The beauty of the Waco design was the fact that the entire nose section, including the cockpit, was hinged and could be swung upward, thus allowing troops or large cargo, such as a jeep or artillery piece, to be loaded and unloaded quickly and easily.

Waco touted itself as the leading manufacturer of civilian aircraft in the United States from 1928 to 1935. Beginning in 1921 as the Weaver Aircraft Company, the firm moved from Lorain, Ohio, to Troy in 1924. In 1929, the name was changed simply to the Waco Aircraft Company.

Building the Gliders

Early on, only four companies were found with aeronautical-related experience and enough available industrial capacity to produce the unpowered aircraft: Waco, Ford Motor Company, Cessna, and Timm. Of these four, only Ford and Cessna had the facilities and organizational framework expected of a prime contractor. Ford was already building jeeps, tanks, and bombers in addition to other military vehicles.

Ford manufactured the gliders at its Kingsford, Michigan, plant where, before the war, “woody” station wagons were produced. During the course of the war, the 4,500 workers at Kingsford turned out 4,190 CG-4As—an average of eight per day—at an average price of $15,400. And Cessna would deliver a total of 750 gliders from its Wichita, Kansas, facility.

The government went shopping for other companies to produce the additional thousands of necessary gliders. The Pratt Read Soaring Company of Deep River, Connecticut, which already had glider-building experience, would deliver a total of 956 CG-4As during the war, while G&A Aircraft of Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, would build 627 of them.

In Minneapolis, the Northwestern Aeronautical Corporation was awarded a string of contracts and eventually manufactured 1,509 CG-4As; 1,470 more were built by Rearwin Aircraft and Engines, Inc. (the company later changed its name to Commonwealth) of Kansas City, Missouri. Another 433 were turned out by the Timm Aircraft Company of Los Angeles. Jenter Corporation (formerly Ridgefield) of New Jersey manufactured 162 of the craft.

Even well-known companies that apparently had no connection to the aircraft industry got involved. For example, the Gibson Refrigerator Company of Greenville, Michigan, built 1,078 of the engineless craft. Plenty of specialty subcontractors also produced component parts for the glider makers; the CG-4A consisted of approximately 70,000 individual parts.

For example, Steinway and Sons, the famous New York piano makers, provided wings and tail surfaces. The H.J. Heinz Pickle Company of Pittsburgh made wings and spar tips. The Anheuser-Busch Brewing Company of St. Louis created inboard wing panels and wooden fuselage frames. Gardner Metal Products, a St. Louis-based coffin maker, made steel fittings. American Lady Corset Company was one of the companies that manufactured the silk drogue parachutes.

A total of 13,903 CG-4As were ultimately delivered during the war, more than all the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers or Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighter bombers manufactured. Even the British received 1,095 American-made CG-4As, which they dubbed Hadrians.

Problems in Production

Many of the chosen manufacturers, however, struggled to build an acceptable product at an acceptable price and deliver it on time. Babcock Aircraft Corporation of Deland, Florida, for example, built 60 gliders inside a circus tent for an average price of $51,000. In contrast, a high-performance fighter such as North American Aviation’s P-51 Mustang cost approximately $58,000 per aircraft.

Four of the 16 companies that eventually received contracts, National, Rearwin/Ridgefield, Robertson, and Ward, had no experience in the field of aviation manufacture whatsoever. The Army’s Materiel Command hoped that if all companies were working from the same set of blueprints and specifications all should be capable of producing high-quality gliders in sufficient numbers and at a reasonable cost. The hope would soon prove to be unfounded.

Because Waco had submitted the winning design, it was awarded the first contract. The order, approved on March 21, 1942, was for 200 nine-place CG-3A gliders. Shortly thereafter, the Army decided that the CG-3A was too small for general combat use, and besides, the only way for troops to exit the craft was to jump out the cockpit windows, so a contract was given to Waco to build 500 of the 15-place CG-4As. During the course of the war, Waco would be given contracts to build 1,074 gliders of various types.

During 1942, however, Waco had production problems and did not deliver its first glider until October of that year. One of the major problems that led to Waco’s inability to meet its goals was that the other prime contractors, who had little or no knowledge of how to build a CG-4A, were constantly sending representatives to camp out at the Waco factory. They badgered the Waco staff for engineering data and production information so they could learn how to build their own gliders. There were some 2,500 pages of blueprints for the CG-4A.

As many as 60 representatives from the other manufacturers had been at the Troy facility at one time or another, a burden that greatly affected Waco’s ability to meet its production quotas. Additionally, Waco, a relatively small company before the war, was continually being bombarded with calls from Materiel Command to design and build additional experimental gliders. All of these extra tasks put a strain on the already understaffed company and prevented it from working at peak efficiency.

Gradually, Waco’s production improved, and in 1943 the company began turning out an average of 43 units per month; in 1944 the average reached 54. The average cost, less than $20,000 each, was also within the government’s budget parameters; only Ford produced gliders for less.

The Poor Inspection Quality of General Aircraft Corporation

Not all of the other glider makers were able to follow Waco’s lead. Companies with little or no aircraft-manufacturing experience were given the opportunity to succeed or fail, and the Army, hard pressed to deliver gliders, was at fault for not more carefully checking out the bona fides of companies that applied for government contracts.

A perfect example was General Aircraft Corporation of Astoria, Long Island, New York. The first contract for 75 gliders was let on March 26, 1942. In July, the order was increased by 154 units, and by another 284 in December, bringing the total to 513 CG-4As; it took a full year for General to fulfill the contract.

To demonstrate how desperate the government was for contractors, General was awarded yet another contract in September 1943 for an additional 500 CG-4As; again, it took a full year to fill the order. The price was high, though. The gliders in the first contract cost an average of $33,770 apiece, while those in the second ran about $28,000 each.

Adding to General’s woes was the fact that the company was held in low esteem by the government. The District Inspector General, after visiting the plant in early 1943, issued a scathing report that noted, among other problems, that the company was poorly managed, had unsatisfactory property accountability procedures, had incomprehensible general contract record keeping, and was doing a less than adequate job of inspecting the wooden and metal parts.

The report concluded that the company president, “having failed to discover and correct these shortcomings, displayed inadequate executive and administrative ability.” It took several months for the company to shape up; even then, it was hard for General to produce gliders for the agreed upon unit price of $20,000.

The $380,000 Gliders of Ward Furniture

Another of those firms that illustrates the rather haphazard way contracts were awarded was Porterfield Aircraft Company of Kansas City, Missouri. In actuality, there was no company; the contract was made with E.E. Porterfield, Jr. as an individual. After promising that he could build gliders, he then formed a company, hired a few employees who claimed to have aircraft manufacturing experience, and went into the glider business.

But little progress was made, and in May 1942 Porterfield sold his company to the Ward Furniture Manufacturing Company of Fort Smith, Arkansas. Trying to build gliders and furniture at the same time proved to be an impossible task, and the company abandoned the table and chair business to fully concentrate on turning out gliders.

Production problems plagued Ward, however, and the quality of the workmanship was below standard. Of the 50 CG-4As ordered, only seven were eventually delivered, and in April 1943 the Army canceled Ward’s contract; the company went back to building furniture.

Given the payments made in advance to Ward and the amount it still owed the company for “future” work, the seven gliders cost the government approximately $380,000 each.

Managerial Problems at National Aircraft

National Aircraft of Elwood, Indiana, was another small, inexperienced manufacturer that had problems gearing up to be a reliable supplier of gliders for the Army. In fact, the Army’s experience with National was one that more resembled a Marx Brothers comedy than a serious effort to produce military aircraft. Although National received an initial order for 30 CG-4As in March 1942 and another 60 in May, the company seemed incapable of ramping up to fill the orders.

So inefficient was National that Major E.W. Dichman, the chief of the Glider Unit in the Production Division at Wright Field, Ohio, notified the Army’s Materiel Command that the company was “a small concern apparently building in a barn,” and in August 1942 Major Dichman recommended that the Army cancel National’s contracts. He observed that the company was organized by a group of local businessmen, none of whom had any background in aircraft manufacturing.

“Managerial problems of the company were severe,” said Dichman, “and to date the contractor had not demonstrated that he had either the facilities or the funds to manufacture gliders.” Only when the company completely reorganized was the contract cancellation rescinded.

Even then, the situation at National failed to improve; an Inspector General’s report revealed that as late as October 1942 the company had only “87 productive and 105 nonproductive workers” in its small, 82,000-square-foot facility. Cancellation was again threatened, and the owners sold out to a St. Louis company, Christopher Engineering.

A report noted: “The change in ownership was not especially salutary, and by February [1943] the situation at National had degenerated to the level of backyard theatricals.” The new owners arrived at the Indiana plant, gave the general manager 30 seconds to write his resignation, and when he refused “had the Auxiliary Military Police eject him from the premises.”

Even the new ownership and management were incapable of correcting the mountain of problems that grew ever higher. The factory was not large enough to complete more than one craft at a time. Nor was the one assembly room wide enough to accommodate the CG-4A’s 84-foot wingspan. The building’s walls had to be knocked out and lean-tos built. Record keeping was still chaotic. The plant, working with highly flammable materials, had serious fire hazards. And a revolt by workers unhappy with all the changes and turmoil resulted in a work stoppage and the holding hostage of the first completed glider.

Major Dichman, completely frustrated by his experience with National, terminated the contract on March 1, 1943. The company’s total output—one glider—was delivered the following month. A report on the situation noted, “Including an unpaid obligation of some $272,000 as of 31 October 1944, this glider, and the lessons learned during the administration of the contract, cost the government $1,741,808.88.”

Low Turnaround at Laister-Kauffmann Aircraft Corporation

Laister-Kauffmann Aircraft Corporation of St. Louis won several CG-4A contracts in early 1942 but like Ward, General, and National, had problems fulfilling them. Of the 210 total CG-4As ordered, the first Laister-Kauffmann was not delivered until January 1943, followed by two more in April.

Because of the slow turnaround time, Laister-Kauffmann’s contract was in jeopardy of being canceled, but production picked up and the company thereafter began building a dozen craft per month at an average cost of $29,000 each. Financial problems beset the company, however, and it appeared that Laister-Kauffmann’s contract might actually be terminated. But in May 1943, Robert P. Patterson, the Under Secretary of War, decided to prop up the firm and subsequently disapproved the recommendations to kill the orders.

In the long run, Laister-Kauffmann turned out to be a steady, if slow, producer of gliders; in addition to the CG-4A, the company was also awarded contracts to develop the XTG-4 and XCG-10A models and produce the TG-4A, a cargo glider.

Another St. Louis firm, Robertson Aircraft Corporation, submitted a bid to build gliders and was given contracts totaling 170 CG-4As. But, despite having engaged in aircraft service and training activities before the war, Robertson proved to be little better than General and National in building the craft. There were endless errors and delays, and a report said that the company was internally “torn by jealousies” and was so hampered by mismanagement and incompetence by persons in positions of authority “that it is disgraceful.” By December 1942, not a single glider had been delivered.

As with National, Major Dichman recommended that Robertson’s contracts be canceled, and on December 31, 1942 the company was notified that its orders were being pulled. An appeal resulted in the termination notice being rescinded and Robertson was given a second chance. However, by March 17, 1943 only six of a scheduled requirement of 23 gliders had been completed and accepted by the government. The contract was again on the chopping block, and the company’s involvement in the glider program was on the verge of being terminated.

Only an intercession on May 1, 1943, by Under Secretary Patterson, who declared he thought it would be cheaper to continue all CG-4A contracts than to cancel those of the poor producers, saved Robertson’s contract. The company redoubled its efforts to satisfy its obligations.

But then something went horribly wrong.

A War Bonds Drive With the St. Louis Mayor

August 1, 1943, was a typical hot, humid day in St. Louis, but the city’s flamboyant mayor, William Dee Becker, was not worrying about the sweat that was soaking his starched white shirt. While being driven to Lambert Field, the St. Louis municipal airport, his mind was on his upcoming ride in a Waco CG-4A glider made by the Robertson Aircraft Corporation. His wife Louise sat sulking next to him in the back seat, miffed that she had been excluded from taking part in the flight.

There was considerable civic pride owing to the fact that two local firms, Robertson and Laister-Kauffmann, had been awarded contracts by the War Department to build some of the nation’s military glider fleet. It seemed that half of the city’s population had turned out to see the public show at the airport and celebrate the economic boom that wartime production had brought to St. Louis.

The streets leading to Lambert Field were jammed with the cars of the curious, and Mayor Becker arrived just a few minutes before the scheduled demonstration was set to begin. One of his missions that day was to encourage the crowd to increase their purchases of war bonds.

A group of dignitaries was waiting for Billy Becker when his limousine pulled onto the tarmac where the glider and its tow plane, an olive-drab, twin-engine Douglas C-47, sat baking in the hot sun. A great cheer went up from the crowd when the mayor and his wife alighted from the car and waved to them.

Then Becker shook the hands of those who were going aloft with him: Charles L. Cunningham, St. Louis’ deputy controller; Max H. Doyne, St. Louis Director of Public Utilities; Lt. Col. Paul Hazelton, supervisor of the U.S. Army Air Force Materiel Command; Thomas N. Dysart, president of the St. Louis Chamber of Commerce; Henry L. Mueller, presiding judge of the St. Louis County Court; Harold A. Krueger, vice president and production manager of Robertson Aircraft; and William B. Robertson, president of the company that had made the glider. At the glider’s controls was Captain Milton C. Klugh from I Troop Carrier Command. His co-pilot was Pfc. J.M. Davis.

Robertson, a retired Army major, was a nationally famous aviator who, back in the 1920s, had established the first air mail and passenger routes between Chicago and St. Louis. He had also been a driving force behind the creation of St. Louis’ airport, named for then-Mayor Albert B. Lambert. The glider in which the group would be flying that day was the 65th completed by his company.

A Tragic Crash

It is unknown if any of those who were about to go aloft and entrust their lives to the CG-4A (besides Robertson) knew of the company’s problems and the Army’s general distrust of the company’s workmanship.

On that hot August day, a few speeches were made, Mayor Becker urged the crowd to buy more bonds, and the crowd pressed forward to get a better look as a silver tow rope was unspooled and connected to the tail of the C-47 and the nose of the glider. The pilots and dignitaries waved again to the throng, entered the canvas and wood contraption, strapped themselves in, allowed a newspaper photographer to take their picture, and then received the well wishes of still disgruntled Louise Becker.

The engines of the C-47 sputtered, coughed blue exhaust smoke, then roared to life. As the thrilled crowd ringing the airport watched, the tow plane pulled the glider to the end of the runway, spent a couple of minutes running up the engines to make sure all was in perfect operating order, then slowly began taxiing toward the takeoff point.

The takeoff was flawless, and both aircraft smoothly took to the air, then banked and flew over the cheering, waving crowd. The plan was for the C-47 to tow the glider some distance from the airfield, release it, and then have it glide back and land at the airport. No one was expecting what actually happened.

Once at the proper altitude, and a second or two after the tow rope was released by Captain Klugh, the passengers inside heard a loud snapping noise, and then the right wing broke off and began fluttering to earth. At the same moment, the glider lurched and it, too, began its plummet.

At first, people on the ground could not believe what they were witnessing; surely this must be some sort of planned stunt, many must have thought. But then the horrible reality of what was taking place before their eyes sank in. Men shouted and women screamed. Some stood transfixed, mouths agape, while others turned away, covering their children’s eyes with parental hands.

The stricken glider seemed to take forever to fall, but when it hit the ground, a great cloud of dust mixed with glider parts being propelled upward and outward from the crash scene rose into the air followed by the sickening crunch of wood and metal slamming into the ground. Immediately, ambulances, police, soldiers, and spectators began rushing toward the heap of debris, but it was too late; all 10 men on board had been killed instantly.

It was one of the blackest days in St. Louis and glider history.

Robertson Aircraft in Court

In the inquiry that followed the tragedy, conducted by the Army Army Forces, the FBI, and both branches of Congress because sabotage was strongly suspected, a laboratory examination uncovered evidence of structural failure; the metal fitting that connected the wing strut to the fuselage had snapped. When the broken part was more closely examined, it was revealed that the metal had been bored to too great a depth, leaving the metal considerably and dangerously thinner than the specifications had called for.

A subsequent investigation of the Robertson Aircraft warehouse parts bins turned up the fact that 25 percent of the same fittings, made by a subcontractor, Gardner Metal Products Company, a St. Louis coffin manufacturer, had the same manufacturing flaw. Only a small percentage of them had been inspected when they were delivered to Robertson.

At a grand jury convened to look into the accident, a woman who had been transferred from the stenographer pool to the inspection department testified that she had received no training prior to her new assignment. Shaken, she said that had she known how crucial the part was, she would have been more careful.

In its report, the grand jury noted, “It was considered odd that the defective part should have been the one and only item on the blueprint specifications that was never able to be properly inspected because there were no instruments or methods suitable for the purpose.”

The grand jury censured Robertson, Gardner, and Robertson’s chief inspector, Herbert E. Couch, for negligence, but indicted no one for criminal wrongdoing. Until her dying day, however, Louise Becker, the mayor’s widow, firmly believed that sabotage was at the root of the crash.

The Army, too, conducted its own investigation. Colonel L.M. Johnson of the Inspector General’s office noted that the crash left him “firmly convinced that the conditions which were in existence at St. Louis prior to this accident are prevalent throughout the country. There is little that the Materiel Command can do to correct conditions.”

A postwar report on the glider program spelled out the many problems: “Poor workmanship, improper methods of manufacture, and general inefficiency at the plants of contractors were all unfortunate aspects of the glider program.”

The Robertson Corporation, as well as the entire American glider program, came under intense scrutiny and criticism after the crash. The muckraking columnist Drew Pearson shone a harsh light on the situation and declared, “The entire U.S. glider program has been woefully neglected.”

Surprisingly, given the accident and the criticism leveled at the Robertson Corporation, the firm received another supplement to its glider contract shortly after the tragedy. Eventually, the company would produce 170 CG-4A gliders.

Still, quality control issues across the country stubbornly remained, and in March 1944, 95 gliders manufactured by Robertson, Waco, and Commonwealth were grounded pending an investigation of improper quality control and the use of unauthorized materials at Robertson and a subcontractor, Anheuser-Busch.

Lessons for the Army on Contractors and Subcontractors

The tragedy led to a major shakeup in how the Army dealt with contractors and subcontractors. Training schools for inspectors were established, proper tools for measuring and testing glider fittings were created, and inspection procedures were carefully spelled out.

A postwar Army Air Forces report on the glider program, in the wake of the St. Louis tragedy, noted, “It is readily apparent that the utilization of small, inexperienced prime contractors in the glider program created a very real problem relating to quality control. The smaller CG-4A contractors needed the assistance of numerous subcontractors to achieve production goals, but they often lacked the skilled inspection personnel and system to insure quality workmanship by the subcontractors.

“At the same time, the Materiel Command was not able to control the quality of the work performed by these subcontractors. In effect, this meant that many of the parts incorporated in CG-4A gliders were not subject to adequate inspection, and the Materiel Command had no assurance that all of the gliders were structurally sound.”

The soldiers who would soon be carried into combat in the gliders, however, never knew to what extent the gliders were flawed. Like most soldiers, they put their faith, justified or not, in their equipment.

This article is excerpted from Flint Whitlock’s book, If Chaos Reigns: The Near Disaster and Ultimate Triumph of Allied Airborne Forces on D-Day, June 6, 1944 (Casemate, 2011).

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments