By Mason B. Webb

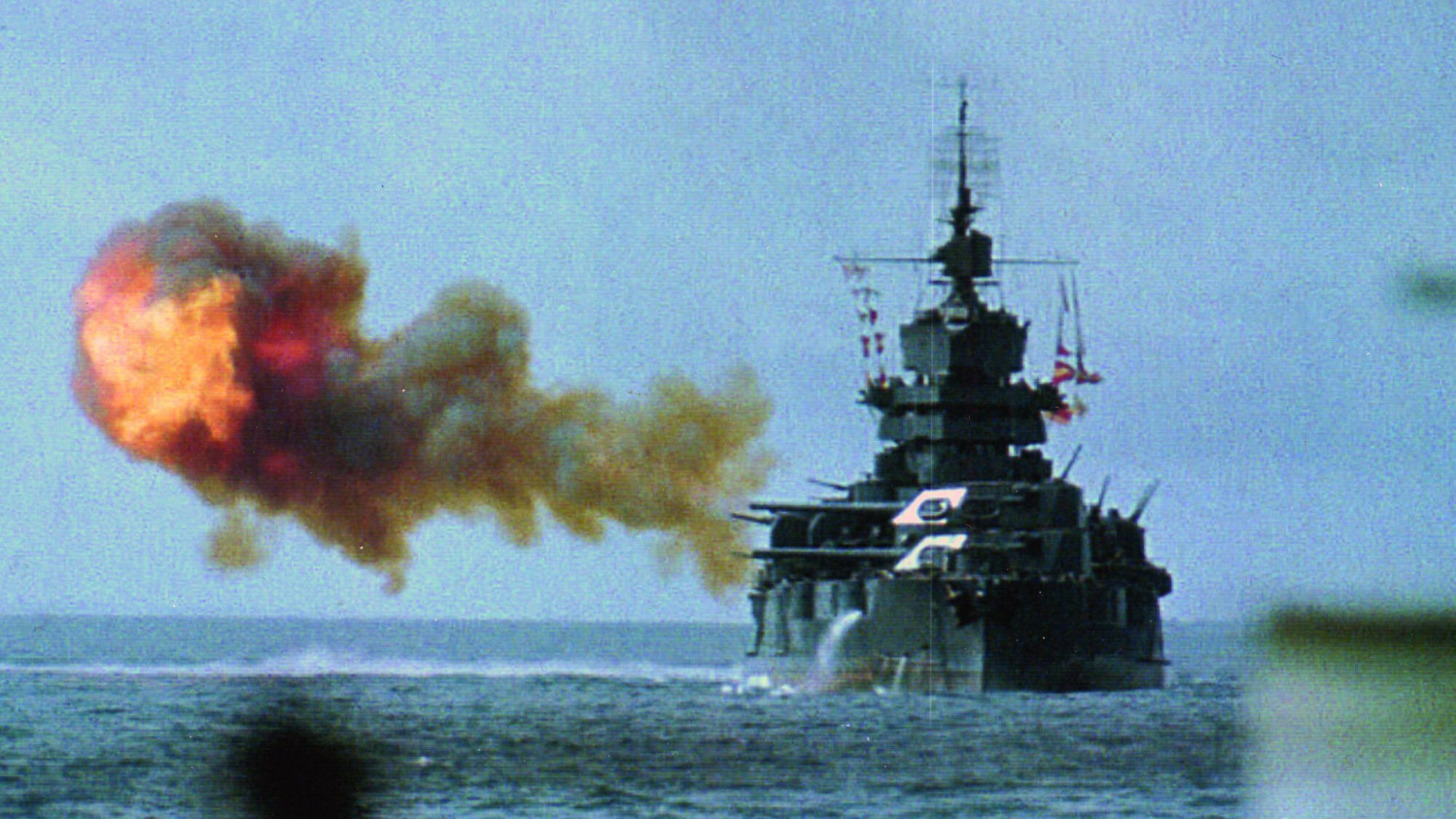

Operation Iceberg, the battle of Okinawa, which lasted from April to June 1945, was the final and largest air-sea-land battle of the Pacific campaign. Strangely, this titanic clash has gone largely underreported.

Correcting that oversight is Bill Sloan, whose monumental work The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa—The Last Epic Struggle of World War II (Simon & Schuster, 2007, 416 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.00) encompasses everything from the grand strategy to the stories of individual participants. Basing his book on official records as well as in-depth interviews with more than 60 veterans, Sloan takes the reader onto the beaches, into blood-soaked foxholes, through shell-blasted villages, and onto the decks of flaming ships and aircraft flying through sheets of lead.

Correcting that oversight is Bill Sloan, whose monumental work The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa—The Last Epic Struggle of World War II (Simon & Schuster, 2007, 416 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.00) encompasses everything from the grand strategy to the stories of individual participants. Basing his book on official records as well as in-depth interviews with more than 60 veterans, Sloan takes the reader onto the beaches, into blood-soaked foxholes, through shell-blasted villages, and onto the decks of flaming ships and aircraft flying through sheets of lead.

During the three-month slugfest, the 110,000 soldiers of the Japanese 32nd Army, knowing that their stand would mean either victory or defeat for Japan, and more than a half million Army and Marine Corp invaders of the U.S. 10th Army were locked in a death struggle that would decide the outcome of the war in the Pacific.

Supporting the boots on the ground were 1,500 American ships, 36 of which were sunk and 360 damaged in wave after wave of kamikaze suicide attacks.

When the smoke of battle finally cleared, General Simon B. Buckner, commander of the 10th Army, was dead—the highest ranking American general to die in World War II. Also dead were some 100,000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen from both sides—plus 150,000 civilians caught in the crossfire. Killed by their own hands in ritual hara-kari fashion were the two top-ranking Japanese generals.

So costly was the horrific battle for the island, which measures only 60 miles long by 18 miles wide, that President Harry Truman realized the enemy would put up a similar or even worse stand if America invaded the Japanese Home Islands. To put a sudden end to the war and the slaughter, he made the fateful decision to use the atomic bomb.

The Ultimate Battle is the ultimate book about heroism, death, and sacrifice that seldom has been more compellingly told. A definite “must-read.”

Rising Sons: The Japanese American GIs Who Fought for the United States in World War II, by Bill Yenne, Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2007, 302 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95.

Rising Sons: The Japanese American GIs Who Fought for the United States in World War II, by Bill Yenne, Thomas Dunne Books/St. Martin’s Press, New York, 2007, 302 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95.

Just Americans: How Japanese Americans Won a War at Home and Abroad, by Robert Asahina, Gotham Books, New York, 2006, 340 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.50.

Within months of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government, worried about fifth columnists and the loyalty of persons of Japanese heritage, began displacing over 100,000 Japanese-Americans living along the West Coast. They had their homes, businesses, and property confiscated and were moved to “relocation camps” in various parts of the country.

Yet, incredibly, thousands of young men from these camps flocked to recruiting centers to join the Army, eager to prove their loyalty to a country that had denied them their rights.

Once trained at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, and deployed to Italy (and later France), the 4,000-man 442nd Regimental Combat Team cut a swath through German formations that made them one of the Nazis’ most-feared opponents. Two new books recount the epic experiences of the 442nd.

Conducting operations with their motto, “Go For Broke,” firmly in their minds, the Nisei won battle after battle, garnered official accolades and public praise, earned thousands of medals and decorations, but paid for their accomplishments with tremendous casualties—over 300 percent. (The men of the unit earned an aggregate total of nearly 5,000 medals for valor—and over 9,000 Purple Hearts.)

With clarity and moving prose, using official documents, memoirs, and interviews with the handful of 442nd veterans who still remain, both Asahina and Yenne tell the story of what General George C. Marshall called “the most decorated unit in American military history for its size and length of service.”

There is no doubt, too, that the outstanding battlefield accomplishments of the Nisei soldiers convinced American politicians that the Japanese American civilians posed no threat to national security and deserved to be released from the relocation camps.

While there is some natural overlap and repetition in both books, each one is well worth reading for, as President Bill Clinton said in a 2000 ceremony at the White House honoring the surviving members of the 442nd, “As sons set off to war, so many mothers and fathers told them, ‘Live if you can, die if you must, but fight always with honor, and never, ever, bring shame on your family or your country.’ Rarely has a nation been so well served by a people it so ill-treated.”

And as General Jacob Devers so aptly put it, the soldiers of the 442nd had “more than earned the right to be called ‘just Americans,’ not ‘Japanese Americans.’”

Both books are very highly recommended.

So Sad to Fall in Battle, by Kumiko Kakehashi, Presidio, New York, 2007, 211 pp., photographs, map, bibliography, hardcover, $24.95.

So Sad to Fall in Battle, by Kumiko Kakehashi, Presidio, New York, 2007, 211 pp., photographs, map, bibliography, hardcover, $24.95.

Those who saw Clint Eastwood’s gripping 2007 film Letters From Iwo Jima saw something American audiences seldom have seen—a view of the Pacific War from the Japanese side. The film was based on this book and, as the dust jacket copy says, “Most Americans know only one side of this pivotal and bloody battle [for Iwo Jima].”

First published in Japan to great acclaim, So Sad to Fall in Battle depicts the epic struggle—in which more than 20,000 Japanese soldiers and over 8,000 American Marines died, with another 19,000 wounded—through the eyes (and letters) of the commander of the doomed garrison, General Tadamichi Kuribayashi.

As Kakehashi depicts him, Kuribayashi was far from the stereotypical fanatical Japanese warrior. Unique among his country’s officers, he refused to send his men on suicidal banzai charges. Instead, he personally walked every inch of the island to plan the positions of the thousands of underground bunkers and tunnels from which his men would make their final stand. As a side note, the flagpole to which the American flag was attached atop Mt. Suribachi, as shown in the famous Joe Rosenthal photo, was a pipe from the water-collection system the general had engineered himself.

On hot, sulfurous Iwo Jima, Kuribayashi rejected the comforts due him as an officer and endured all the hardships with his troops, knowing that neither rescue nor reinforcements were coming his way. And, as the tide turned against him, Kuribayashi displayed his true mettle: though offered a safer post on another island, he chose to stay with his soldiers, fighting alongside side them in the brutal, no holds barred clash, and eventually falling with them.

There were very few Japanese survivors of the battle (just over 200), but author Kakehashi was able to track down many of them and record their memories of the battle and their courageous leader.

Yes, the Japanese were ruthless in battle and in their occupation of other countries and treatment of POWs, but So Sad to Fall in Battle is a tremendously moving, sobering experience, full of reflections and observations about the human cost of war. Not to be missed.

Hitler’s Siegfried Line, by Neil Short; Hitler’s U-Boat Bases, by Jak Showell; and Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, by Anthony Saunders, all from Sutton Publishing, London, 2007, photos, maps, diagrams, indexes, various lengths, each $24.95.

Hitler’s Siegfried Line, by Neil Short; Hitler’s U-Boat Bases, by Jak Showell; and Hitler’s Atlantic Wall, by Anthony Saunders, all from Sutton Publishing, London, 2007, photos, maps, diagrams, indexes, various lengths, each $24.95.

In the history of warfare, no nation built more—or more formidable—defensive works than Nazi Germany. Hitler was obsessed with fortifications, and the bigger, the better.

He had Dr. Fritz Todt, the head of Germany’s construction arm, Organization Todt, and his armaments minister Albert Speer, constantly adding to Germany’s seemingly indestructible inventory of gun and observation bunkers, casemates, individual fighting positions, tank barriers, submarine pens, missile- and rocket-launching ramps, beach obstacles, and underground headquarters and command centers—all designed to make Germany immune from invasion and defeat.

As the authors of these three fine, well-researched, and profusely illustrated books (with many then-and-now photos) point out, tens of thousands of men—some conscripted laborers—worked for years to build immense structures that would be unfazed by time and enemy munitions. Billions of Reichsmarks and millions of man hours went into the creation of these incredible reinforced concrete structures, but it was all for naught; in the end, the fortifications designed to keep out the invaders failed miserably. The Atlantic Wall at Normandy, for instance, was breached by the Allies in the span of a morning.

Fortunately for fortification buffs, many of these once mighty construction projects still stand as tourist attractions or have been put to civilian use, some a little worse for wear, but still awe provoking in their size, scale, and obvious craftsmanship that was designed to last as long as the “Thousand-Year Reich.”

Besides being filled with interesting, little-known facts, these books can also serve as a guide to the many sites that still exist for the battlefield visitor.

Anyone who finds military fortifications intriguing will be fascinated by any or all of these three books.

Encyclopedia of Elite Forces in the Second World War, by Michael E. Haskew, Amber Books, London, 2007, 192 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Encyclopedia of Elite Forces in the Second World War, by Michael E. Haskew, Amber Books, London, 2007, 192 pp., photographs, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Although elite forces have been around since the dawn of warfare, it was not until World War II that they were extensively employed by virtually all of the major combatants.

Just the knowledge that a relatively small band of highly trained, highly specialized troops (think American paratroopers dropping behind enemy lines at Normandy, or Peiper’s kampfgruppe during the Bulge, or Japanese kamikaze at the Battle of Leyte Gulf) was facing them was enough to give opposing commanders and forces pause.

The stories of many of these elite forces—paratroops, rangers, commandos, special air and naval units, and the like—have been captured in a highly interesting and factual compendium by WWII History magazine editor Michael Haskew. Within this book’s 192 pages are concise, intriguing histories of many elite formations that served in American, British (and Commonwealth), German, Belgian, French, Italian, Japanese, and Soviet armies, air forces, and navies, and struck fear into the hearts of their enemies.

Here the reader will find little-known information about such groups as the British SAS, the American-manned RAF Eagle Squadrons, Popski’s Private Army, Darby’s Rangers, the Waffen-SS, Long Range Desert Group (the Desert Rats), Flying Tigers, Special Boat Service, and scores more. Each entry is studded with plenty of little-known facts, and Haskew covers each unit’s battlefield failures as well as its successes.

Lavishly illustrated with over a hundred high quality color and black-and-white photos, Haskew’s work will be applauded by researchers and history buffs alike. A “must have.”

Hitler’s Headquarters: From Beer Hall to Bunker, 1920-1945, by Blaine Taylor, Potomac Books, Washington D.C., 2007, 209 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.95.

Hitler’s Headquarters: From Beer Hall to Bunker, 1920-1945, by Blaine Taylor, Potomac Books, Washington D.C., 2007, 209 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $29.95.

In this well researched, profusely illustrated volume, Blaine Taylor has created a fascinating photographic history of Adolf Hitler’s many headquarters, offices, command posts, private residences, and even mobile headquarters from which the Führer planned his rise to power and directed his war against East and West. Taylor recounts the background history and physical description of each location while relating the importance of these locations to the larger story of Nazi Germany and World War II.

Included in this book are such well-known spots as the Braunhaus (Nazi Party HQ in Munich), Munich’s Hofbräuhaus (site of an early attempt on Hitler’s life), the old and new Reich Chancellery buildings in Berlin, the Berghof and “Eagle’s Nest” at Obersalzberg, the Wolfschanze at Rastenburg, and the Fuhrerbünker in Berlin.

Also included are little-known locations such as the room Hitler rented in Munich in 1913-1914, the Sterneckerbräu beer hall (the “birthplace” of the Nazi Party), Hitler’s disguised headquarters in the Ukraine, and even photos of his special train. Several of the visuals are then-and-now comparison shots—many of them published for the first time.

A number of these buildings still exist, and Taylor’s comprehensive work will serve as a fine guidebook for the traveler who wishes to seek out the actual places where history was made. Highly recommended.

At Leningrad’s Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North, by William Lubbeck, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2007, 256 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $32.95.

At Leningrad’s Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North, by William Lubbeck, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2007, 256 pp., photographs, maps, hardcover, $32.95.

What was life like for the average German soldier on the Eastern Front? In 1940, a young Wehrmacht draftee named Wilhelm Lübbecke (he changed it to William Lubbeck after the war when he moved first to Canada and then to the U.S.) discovered the answers firsthand after his division took part in the invasion of France and then transferred to the East.

The next year, he found himself in on the invasion of the Soviet Union. Lubbeck’s unit, the 58th Infantry Division, made the deepest penetration into Leningrad’s suburbs before it was pulled back to take part in the brutal siege of the city. Fighting the terrible winter conditions as well as the enemy, Lubbeck’s unit managed to hang on, but barely, and suffered horrendous casualties. In 1943, he returned to Germany and trained to become an officer. After being commissioned, he returned to his old company and took command, guiding it on a year-long retreat from Russia.

Taken prisoner, Lubbeck survived a Soviet POW camp, struggled to exist in postwar East Germany, and escaped to the West to begin to build a new life.

This is a remarkable book about a remarkable soldier who went through hell and ended up making a success of his life in a new land. Inspirational and strongly recommended.

Short Bursts

The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Kesselring, Greenhill, London, 2007, 320 pp., photographs, maps, index, softcover, $24.95.

The Memoirs of Field-Marshal Kesselring, Greenhill, London, 2007, 320 pp., photographs, maps, index, softcover, $24.95.

Known as “Smiling Albert” to friends and foes alike, behind the friendly exterior the dashing, paradoxical Kesselring was a formidable warrior and a top tactician, especially when it came to defense. A young officer in the “Great War,” in 1935 he transferred from the Army to the Luftwaffe, where he became Luftwaffe Chief Hermann Göring’s deputy and commanded air fleets during the Battle of Britain.

In this reprint of his 1960 memoirs, Kesselring discusses with candor his involvement in the many major battles in which he was engaged—North Africa (sharing the direction of the command with Erwin Rommel), Sicily, and Italy, where his leadership brought the Allied drive to a virtual halt.

In March 1945, Hitler appointed Kesselring Commander-in-Chief West, and gave him the responsibility for holding off Allied armies charging through France, Belgium, and Holland—an impossible task. But if anyone could do it, it was Kesselring, who had supplanted Rommel as Hitler’s favorite general. That he ultimately failed to prevent defeat in the West was no reflection on his abilities.

A very worthwhile study of command at the highest levels.

Thanks for the Memories: Love, Sex, and World War II, by Jane Mersky Leder, Praeger, Westport, CT, 2006, 185 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

Thanks for the Memories: Love, Sex, and World War II, by Jane Mersky Leder, Praeger, Westport, CT, 2006, 185 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

World War II turned the world upside down. Thirty million American men and women were uprooted during the war, either as members of the military or as civilians in search of work in the defense plants. Away from the strictures of family and church, they tested the limits of sexuality and morality—and often broke the rules.

In her highly interesting study of wartime morés, Jane Mersky Leder explores, with the help of scores of interviews of men and women of the Greatest Generation, life on the home front and the sex lives of GIs overseas and at stateside bases. She tells a story that has rarely been mentioned before, discussing such formerly taboo topics as prostitution, “cheating,” contraception, unplanned pregnancies, gays in the military, “Good-Time Charlottes,” love, marriage, and much more.

Thanks for the Memories fills in the unspoken gap about some of the things that really went on during World War II. A highly interesting read.

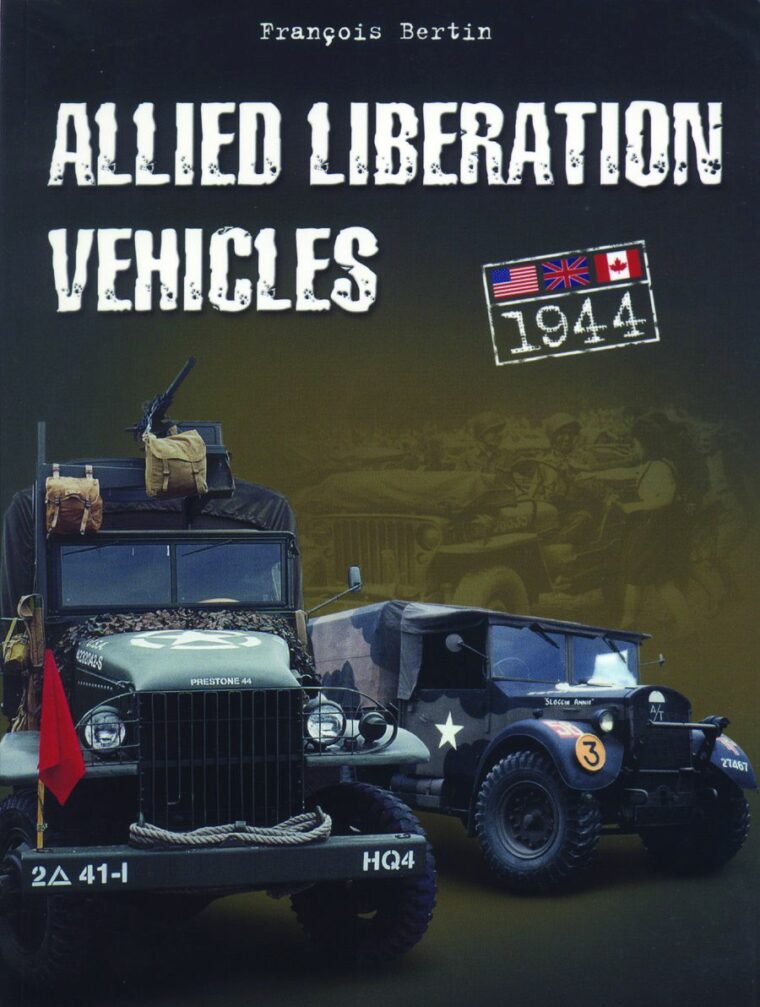

Allied Liberation Vehicles, by François Bertin, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2007, 128 pp., photographs, softcover, $24.95.

Allied Liberation Vehicles, by François Bertin, Casemate, Philadelphia, 2007, 128 pp., photographs, softcover, $24.95.

Chock full of 280 crisp, clear color photographs, all of pristine, restored American, British, and Canadian vehicles taken at reenactments and military vehicle shows in Europe and the United Kingdom, Allied Liberation Vehicles is a fine book for anyone who owns or is restoring an MV, or those who simply have an interest in the myriad vehicles that helped win WWII.

The informative text, translated from the original French, covers the gamut: listings of manufacturers, production numbers, vehicle markings, model classifications, and charts of specifications of all the types shown. The author admits, however, that he was selective in his choice of which vehicles to include, and that the book is not an exhaustive catalog of every Allied vehicle. However, the nearly 60 different types he does feature are all pictured and described to their maximum advantage.

Covering everything from motorcycles to jeeps to trucks to tracked vehicles to tanks, Allied Liberation Vehicles is guaranteed to provide many hours of enjoyment for the military vehicle enthusiast.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments