By Andre Bernole and Glenn Barnett

The world was understandably shocked when France capitulated to Nazi Germany in June 1940, but not all Frenchmen accepted their country’s humiliation. Chief among them was General Charles de Gaulle, who fled to England to continue the struggle as the self-proclaimed head of the Free French government in exile. Almost alone at the beginning, others would join his cause.

Individually and in small groups, pilots of the French Air Force (Armée de L’air) made their way out of Vichy-controlled France, North Africa, Madagascar, and even Indo-China to join the Free French forces.

One such pilot, Louis Delfino, had scored several aerial victories against the Germans before France’s capitulation. He then flew for Vichy at Dakar where he scored a victory over an RAF Wellington bomber before joining the Free French fighting on Britain’s side. By war’s end, Delfino’s official score against the Germans would be 17 victories, including seven in Russia. (It should be noted that recognized victories in the heat of battle are subjective and there is often more than one list of scores. The victories cited here are the “official” version of Normandie-Niemen pilots’ scores.)

Another French pilot, Constantin Feldzer was born in Ukraine in 1909. In 1917 his father immigrated with his family to France where, in 1929, Feldzer took up flying and flew missions during the Spanish Civil War. Against orders in June 1940, during the Sitzkrieg, or Phoney War, he shot down an Me-109 that had intruded into French airspace. After France’s surrender and the establishment of the new collaborationist government at Vichy, Feldzer decided to defect. His perilous journey included imprisonment by the Vichy authorities in North Africa and subsequent escapes. When the Allies invaded North Africa, he was quick to join them and the Free French.

Soon, many of these stateless pilots had their property confiscated by Vichy and sentences of death imposed on their heads. Defiant, they formed their own fighter and bomber squadrons within the RAF, where they played an important but largely unsung part in the Battle of Britain. At least 13 French pilots were awarded the bronze Battle of Britain bar for their services in the skies over England between July 10 and October 31, 1940. Other Frenchman served in regular RAF squadrons, most notably the future Prime Minister of France, Pierre Mendés-France (1954-1955).

De Gaulle Sidelined by the Allies

De Gaulle believed that it was important for French soldiers to fight alongside the Allies and against the Germans anywhere possible. When the Soviet Union was invaded in June 1941, de Gaulle declared, “Without agreeing to discuss now the depravity and even crimes of the Soviet Regime, we must declare, as Churchill did, that we’re very sincerely with the Russians as they are fighting the Germans.”

He reached out to Stalin with offers of assistance and a request that his Free French organization be recognized as the legitimate government of France. Stalin broke relations with Vichy when Russia was invaded but he hedged about recognizing de Gaulle. He did not think that de Gaulle had much to bring to the table and, besides, in the summer and fall of 1941, he was preoccupied with the German invasion.

De Gaulle’s relations with the United States were no easier. After Pearl Harbor, de Gaulle offered to send a squadron of Free French fighter pilots to serve with the United States, proposing to call them the “Lafayette Escadrille” (or Escadrille de Lafayette) in honor of the American pilots who served with France in World War I. The U.S. Army Air corps turned him down.

Even after entering the war following Pearl Harbor, the United States continued to maintain diplomatic relations with the Vichy government, and de Gaulle was frozen out. To Franklin Roosevelt, de Gaulle was a demagogue who had never been legitimately elected by the French people. Churchill reluctantly followed FDR’s lead. It soon became apparent to de Gaulle that the Anglo-American alliance would overlook French interests. He was determined to counter this by building bridges to Stalin.

Groupe de Chasse 3: An Air Force For Stalin

In March 1942, de Gaulle ordered that a new group of Free French fighter pilots and ground personnel be organized; they would be offered to Stalin to fight alongside the Soviet Air Force. Stalin tentatively accepted this idea, provided that the French pilots were of the highest caliber. Thus began a remarkable saga of courage and fortitude.

De Gaulle dispatched Albert Mirlesse to Moscow to be the French representative for the proposed air squadron. Mirlesse was the French-born son of Russian Jewish émigrés who fled the czarist police in 1905; he spoke fluent Russian and worked closely with the Soviets to iron out the details.

By September 1942, French pilots began gathering in Syria, which was newly liberated from Vichy control. There they trained and honed their flying skills while studying Russian.

The new force was known as Groupe de Chasse 3 (GC3). This was the equivalent of an RAF wing with three squads (or escadrilles), though it would be awhile before the new Groupe was up to full strength.

All Free French squadrons were named after French provinces. GC3 took the nom de guerre of “Normandie” (Normandy). Its insignia, borrowing that of the province of Normandy, included two golden leopards, one above the other, on a red background. Beneath the lions was a white lightning bolt, the symbol of their Soviet Division.

For de Gaulle, France naturally came first. When visiting Joseph Pouliguen, the first commandant of GC3 in Syria, he remarked, “Above everything, when you have any decision to make, always ask yourself: what is the interest of France in that matter?”

Pouliguen was a Great War veteran who had been wounded as an infantryman. He then took up flying and completed 30 missions in a Breguet XIV, a large biplane used as a bomber and for reconnaissance, before war’s end. He then flew 30 missions against the emerging Bolsheviks. He reenlisted in 1939 but resigned his commission in the Armée de L’air before escaping France to join the Free French.

Political Games in the Soviet Union

The next task was to get the pilots and crew to Russia. It was decided that sailing from England to Murmansk was too dangerous because of the very active menace of U-boats which were taking a heavy toll of Allied shipping in the North Sea. Another route had to be found.

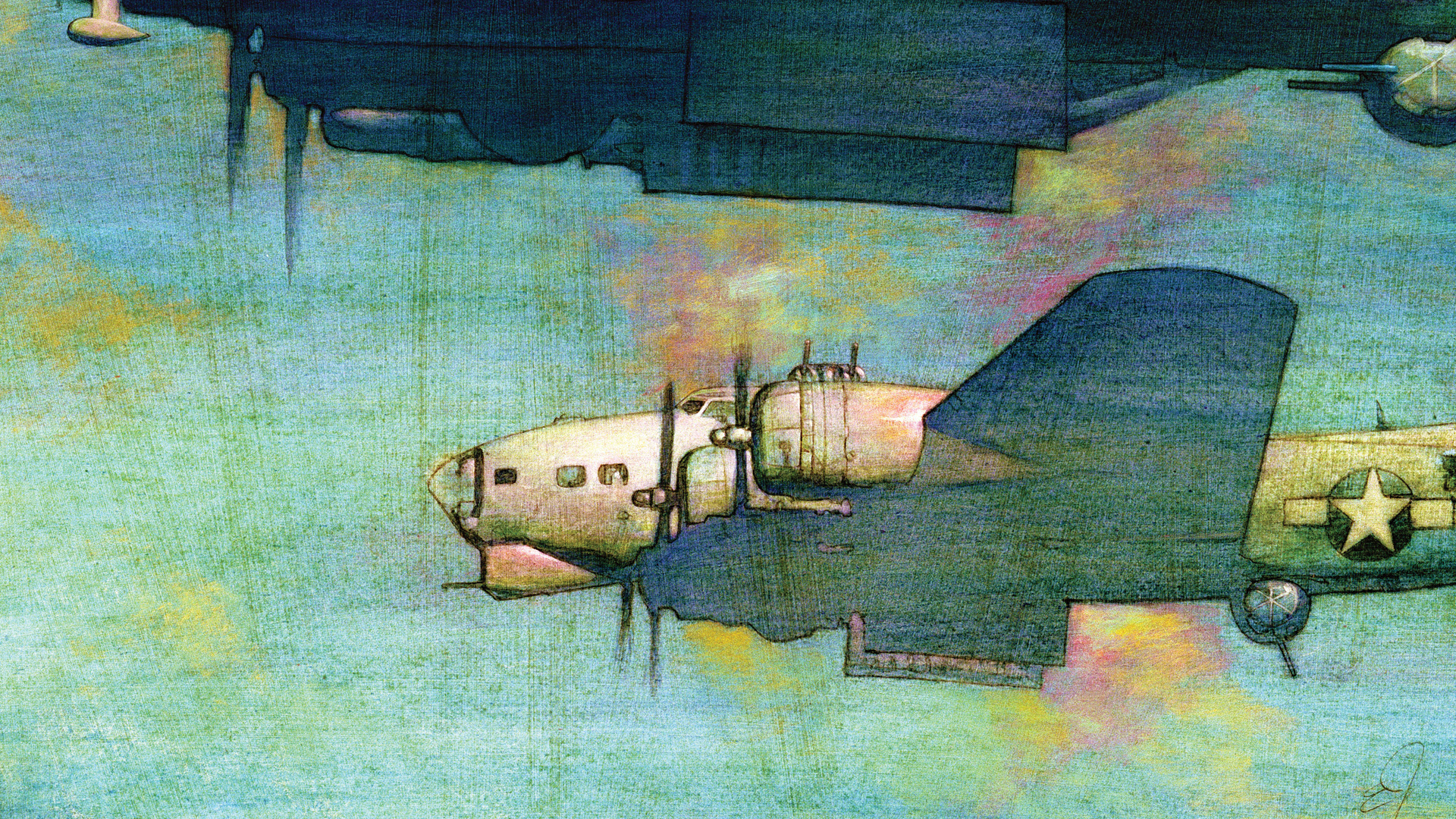

In November 1942, three American DC-3s from Egypt were made available to take the group of 12 pilots, their ground crews, and equipment first to Baghdad and then to Tehran. They flew on to Russia on three Lisunov LI-2s (which were essentially Douglas DC-3s built under licence in the USSR). By November 28, the pilots and ground crews assembled at their training center at Ivanovo, 125 miles northeast of Moscow.

The pilots were under no illusions about the nature of the Soviet government. Pilot Roland de la Poype would later write, “As soon as we reached USSR in 1942, I was not fooled about the reality of the Soviet regime. Along with all my friends, I was not seriously listening to the conferences organized by the political commissar. But all of us were strongly united by our determination to fight the Nazis, and that was all. Even at the worst of the Cold War, the friendship bonds we had during the war were still there.”Coming from Syria, they were not ready for the extreme cold of the Russian winter. Temperatures of 30 to 40 degrees below zero Fahrenheit were common. But they were warmly and officially welcomed into the Soviet Air Force, which providently provided them with some winter gear. The pilots were assigned to heated cabins with three or four men to a room. Their rations consisted of porridge of millet seeds and an occasional bit of sausage of questionable origin.

Their willingness to fight did not keep them from being tested. One night Michel Schick, a French pilot and liaison officer who spoke Russian fluently, was attending a circus in Moscow. There he met a lovely, young Russian woman who invited him back to her apartment. There with a friend, a war widow, they drank vodka and flirted. Suddenly one of the women asked Schick if he had heard of the Stalinist purges in which thousands had been killed. They called Stalin “a crazy pig” and worse. Smelling a trap, Schick replied that a French officer would never listen to such “shit.” He stood up and abruptly left.

Upon returning to base, Schick informed Commandant Pouliguen of the incident. Together they confronted an officer of the Soviet Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Russian was told that the French had come to fight and did not have time for these games. They suspected that the culprit was the Soviet political liaison officer assigned to them. Within a week he was replaced by a Lieutenant Kounine who spoke perfect French. (Like all units in the Soviet military, Normandie was assigned a political officer whose job it was to monitor the opinions of his charges. Despite this, Kounine was accepted as a part of Normandie and became fast friends with everyone.)

Choosing a Fighter For the Air Group

Soviet authorities offered their French guests the choice of using Lend-Lease American or British planes or the Soviet-built Yak 1. When consulted, de Gaulle told Commandant Pouliguen to choose the best fighter without thinking about the country it came from.

On December 4, 1942, Colonel Choumow, the Russian commander at the Ivanovo training base, designated Captain Pavel Drousenkow as the lead instructor for the French pilots. Choumow told his guests, “Pavel will show you all the planes that we can equip you with. I believe that your pilots already know American and English planes; we have Bell P-39 Airacobras, Hurricanes, and Spitfires. Pavel will also show you our fighter, the Yak1. You’ll then choose whatever you like.”

Commandant Pouliguen wanted to know everything about the different planes. He consulted with Lieutenant Michel (head of the mechanic team) and his pilots. He was especially interested to hear from the most experienced pilots: Albert Durand (nine victories, two shared), Marcel Albert (nine, with 14 shared), and Marcel Lefèvre (seven, with three shared), who had all logged many hours in Spitfires with the RAF. His own experience and that of another experienced pilot, Albert Littolf (seven, with two shared), allowed him to compare the French planes such as the 1940 frontline fighter Dewoitine 520, with which most of the pilots and mechanics were familiar. (Of the four pilots mentioned here, only Albert would survive the war.)

The American Airacobra was appreciated as a ground-attack tank-buster, but it made for a poor fighter. English airplanes needed very precise technical maintenance and a fairly smooth runway for taking off and landing. The French learned that their bases would be very close to the front––between three to six miles––with snow on the ground all winter, slushy mud in spring or autumn, and clouds of choking dust in summer.

The Yak, with its low-pressure tires, had a distinct advantage on rough dirt runways. Though rustic, it was robust and efficient. Its wood and aluminium alloy construction made it very light. Unfortunately, the pilot was not well protected. There was only a bullet-proof back seat and front windscreen, but the fuel tanks automatically filled with exhaust gases as the fuel was consumed to prevent explosions.

The Yak engine was very simple and familiar to the French mechanics as it was derived from a licensed French Hispano-Suiza 12 Y (similar to that of the Dewoitine 520), which produced a speed of 350-360 mph.

The Yak’s armament included a nose-mounted 20mm cannon with 150 rounds and two wing-mounted 50-caliber machine guns housing 700 rounds. The Yak was everyone’s first choice.

“The Best For Us is the Russian Plane”

The Russians were flattered but not everyone was happy. In Moscow, Mirlesse was called to the American embassy by Ambassador William Standley and in the presence of an English air marshal was asked to explain that decision. Mirlesse replied, “We know that Hurricanes are already inferior to the Focke-Wulf [Fw-190]; our pilots have had that experience. And, what’s more, you are delivering only second-rate planes to the Soviets. We do understand that you’re keeping the best for your country, but you’ll have to understand that we also want for our men the best there is for use here. And the best for us is the Russian plane.”

The Yak aircraft took its name from its chief designer, Alexander Yakovlev. Before the war, Yakovlev had built racing planes. In 1938, he won a competition sponsored by the Soviet government for a new fighter plane. His prototype, built largely of wood, flew in March 1939 and won the design competition. With refinements, it was able to fly at 370 mph by January 1940 and went into mass production shortly thereafter. With admirable foresight, the production factory was built east of the Ural Mountains where it would be safe from future German bombing.

The Yak did have its faults. In most areas of performance it was inferior to the German fighters. It flew without radios because Russian radios were so bulky and unreliable that, even when available, many pilots preferred to do without them.

The Normandie Squadron was to be a part of the 303rd Fighter Air Division of the Soviet First Aerial Army. As such, their planes sported Soviet markings; the red star was painted on the tail and both sides of the fuselage. A white lightning bolt was painted along the fuselage. The French then added the Normandie emblem under the cockpit. The nose that spun with the propeller, called the “spinner,” was painted with the distinctive red, white, and blue tricolor of the French flag.

Primitive Accommodations For the Normandie Squadron

In February 1943, Lt. Col. Jean Tulasne (eight victories, three shared) became the second commandant or wing commander. Tulasne was a graduate of the French military academy Saint Cyr and had served with the Armée de L’air before the war, and with the RAF at Tobruk, where he had flown a Hurricane in combat. Besides being in overall command, Tulasne frequently flew combat missions himself.

After two months of cold-weather training that stressed navigation over the vast, featureless white terrain, the 54 men––pilots and ground crew––and the 14 Yak-1s of the French squadron were moved to a primitive dirt airfield southwest of Moscow where they were assigned to their division.

The 303rd was commanded by General Géorgui Zakharov, who would take a special interest in their performance. Zakharov, born in 1908, was alone in the world when his parents died in the 1920s, so the Soviet Air Force became his new family. He fought in the Spanish Civil War and against the Japanese in the 1939 Battle of the Khalkhin-Gol on the border between Manchuria and Mongolia. Although, as a commanding officer he was not supposed to fly, by the end of the war he would have 18 victories.

Normandie took part in its first combat mission in March 1943 when the unit flew escort for a flight of Soviet Pe-2 ground-attack bombers. The spring thaw and rains had come to Russia and the dirt airfields were now slushy morasses. The overworked ground crews had to physically manhandle the aircrafts’ wheels from muddy ruts to get them moving.

The improvised airfields were very primitive. Usually there was no electricity, heat, or running water. Showers consisted of cold water falling from a large can punched with holes. Accommodations were iffy, no better than the infantry, and obtaining food at a time when thousands of Russians were starving to death was a continual problem. There were also numerous pests to contend with; bedbugs, fleas, gnats, mosquitoes, and tapeworms would plague the combatants of both sides.

At this stage of the war the Soviets did not have radar. Incoming enemy planes were sometimes spotted by forward ground observers and phoned in (if phone lines were available). Often communications were delivered by motorcycle messenger over treacherous Russian roads.

First Kills For the Normandie Squadron

On April 5, 1943, Normandie pilots scored their first two kills when two Fw-190s attacked a flight of Pe-2s under their protection. Attacking from above, the French-piloted Yaks surprised the Germans and shot them down. A week later, Normandie suffered its first losses when three of its pilots failed to return from a mission.

The German high command soon learned of the presence of the Free French pilots and was furious. An order went out to the front from General Wilhelm Keitel that any French pilot captured while flying for the Soviets should be shot immediately upon capture and their families arrested. His reasoning was that the French pilots were in violation of the armistice between Vichy France and Germany; more than one Normandie pilot would meet his end by execution. One pilot, Roger Pinon, who was forced down behind enemy lines on August 1, 1944, was shot in the back of the head while still inside his plane.

Within weeks after the capture of Aspirant (Officer Candidate) Yves Bizien on April 13, 1943, his family—parents and three brothers—was arrested by Vichy police and sent to a concentration camp; only a younger brother survived the war.

General Zakharov was sympathetic to the French for the loss of their friends, assuring them that they would be able to avenge their fallen comrades “a hundredfold.” On April 15 he showed a special trust in the French by placing a patrol of six Yak-7s with Soviet pilots under French command. In the spirit of cooperation among allies, Commandant Tulasne assigned a Russian captain to lead a mixed patrol of six French and six Russian planes on a suppression mission to keep German planes grounded during a bombing raid.

For the next two months the Normandie Squadron would continue gaining frontline experience, flying interdiction missions or cover for the Pe-2 and the more famous Il-2 Sturmovik ground-attack plane. Protecting these planes meant flying at low altitude and continually watching overhead (and below) for the enemy. Typically, the P-2s and Sturmoviks would fly at around 1,000 feet while the Yaks would fly cover overhead at 2,600 feet.

Air Battle Above Kursk

In July 1943, Normandie would be involved in one of the greatest battles of the war. The Battle of Kursk is remembered as the largest tank battle in history, but this ignores the importance of the battle in the air. The Germans amassed 1,800 aircraft for the epic struggle while the Soviets committed 2,000 planes.

Based between Moscow and Kursk, Normandie saw action in the Orel sector, north of the embattled city. When the fight was over, Normandie claimed 17 confirmed kills and several probables. At the same time, they lost six of their pilots to enemy action. One of these was Commandant Tulasne.

Tulasne was replaced by one of the Normandie veterans, Pierre Pouyade (three victories, four shared). Before the war Pouyade had commanded a French fighter unit in Cambodia. When the Japanese were “invited” in by the Vichy government in Hanoi, he quickly tired of their belligerent and dominating attitude. He escaped to China in an old biplane that ran out of fuel as he landed. In China he met General Joseph Stilwell but received no help from the Americans as the U.S. State Department still recognized Vichy.

As a commander, Pouyade was a flamboyant character who has been compared to Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, the irascible U.S. Marine Corps flying ace who was awarded the Medal of Honor. Once, when grounding a pilot for forgetting to lower his landing gear, Pouyade took away the man’s poker privileges for eight days. But the very next night Pouyade invited the man to a poker game because he was short a player. Another time, Pouyade had an affair with a married Russian woman. When her husband complained to the authorities, General Zakharov protected Pouyade from official criticism; he could not afford to lose the Frenchman.So, even though Pouyade provided Stilwell with a stolen map of the Japanese air combat system in French Indochina, the general said his hands were tied; Pouyade was on his own. He laboriously made his way to London to join the Free French before joining Normandie.

Plight of the French Mechanics

After the epic battle at Kursk, the Normandie pilots moved westward to a forward air base but their French mechanics did not go with them. After eight months in service, they went home and Soviet mechanics took their place.

It had been hard duty for the French ground crews. While the pilots had been received with honor and camaraderie, the mechanics were not. Upon arrival, they soon learned that they had to fend for themselves in subzero weather. Awake at 3:00 am, they ran warm oil and water through the cooling system of the planes to warm them sufficiently to start their engines at dawn. They could not remove their gloves to do intricate work for more than 15 to 20 seconds without suffering frostbite to their fingers.

About a third of the mechanics were experts at their job and hoped to be promoted to become pilots, which was the French practice dating from World War I; the Soviets had no such system of promotion and training. On the other hand, Soviet mechanics who were certified became officers; the French did not have that system. Their mechanics were always noncoms, with no chance to advance.

Another third of the mechanics were very enthusiastic about the adventure of going to Russia but were relatively untrained. Their on-the-job training was brutal. The final third of the mechanics were troublemakers who had been bounced from other units. They fared the worst.

While pilots got housing and decent food (when it was available), the French mechanics, like Soviet mechanics, were ignored and were basically on their own. At a time when the civilian population was starving, soldiers and pilots got first priority for food. The mechanics did not fall into that category.

Furthermore, they were expected to work 14-hour days. In the harsh winter of 1942-1943, they had to improvise their own shelters and hunt rabbits and (to the horror of the Russians) even cats for food. Disease also took a debilitating toll.

Russian Mechanics Join the Squadron

The mechanics were ready to leave, and few in the West were willing to take their place, so Soviet mechanics filled the void. The French pilots were at first leery about this proposition but the Soviets proved more than capable. With the addition of 100 Soviet mechanics to their numbers, Normandie became a very mixed squadron.

Some of the new Soviet mechanics worked hard to learn French. The pilots’ favorite mechanic was Sergueï Agavelian. A brilliant engineer, Agavelian could easily size up what each plane needed in terms of maintenance. To add to his popularity, he quickly mastered the French language. Meanwhile, many of the pilots learned much of their Russian from girls they met while on leave in Moscow

The bond between the pilots and mechanics was cemented later on July 15, 1944. It was customary when moving to forward bases for a pilot to squeeze his mechanic into his plane so that he would be available immediately to work on the plane if needed. On that day, while making such a move, pilot Maurice de Seynes became blinded by a gas leak that spewed into the cockpit. He was ordered to bail out but refused to leave his mechanic, Lieutenant Vladimir Bielozoub, tucked into the back without a parachute. He attempted to land but crashed, killing them both. They were buried side by side near the airfield, and local children adorned their graves with red, white, and blue flowers.

Recruiting Pilots For Normandie

Normandie had another problem after the Battle of Kursk. The unit’s pilot losses had been high and replacements were not forthcoming, prompting fears that the squadron would be disbanded. Just in time, the Ukrainian-born Constantin Feldzer came to the rescue. After his stint in a Vichy prison in Algeria, he found himself flying for the liberated French authorities. These were not de Gaulle’s men but ex-Vichy officials who had switched sides. As a Gaullist, he was not popular among them. Nevertheless, on one mission he scored a victory over a German Ju-88, though it was never acknowledged by his superiors.

In the summer of 1943, Feldzer met a Soviet officer desperately trying to recruit pilots for the Normandie Squadron. Andreï Vichinsky was posted by the Soviet government to establish relations with the Free French in North Africa. The Soviets were realists. They knew that, compared to the massive scale of the armies fighting, Normandie was almost insignificant. But symbolically, as an ally fighting alongside Soviet forces, the unit was very important. Vichinsky recognized the value of the Normandie Squadron but could not find anyone in the French Air Force who was sympathetic. Feldzer took up his cause.

There was one catch. The pilots he wanted were already assigned to other units and did not have permission to leave. Feldzer solved the problem in a unique way. Convinced that they would be eager to fight, he sent counterfeit telegrams to men he had known for 10 years in the Armée de l’air, ordering them to report to Algiers. When they arrived, he asked them if they wanted to join Normandie. Fourteen pilots were recruited in this way and together they all flew to Moscow. The new pilots arrived to replace casualties and to fill out the three escadrilles that composed the Groupe. Normandie was back in business.

Flying the Newer Yak-9 Aircraft

By the end of August, the squadron had 42 confirmed victories. They also began receiving a trickling of the newer Yak-9T. This version replaced the nose-mounted 22mm cannon of the Yak-1s with a 37mm cannon. To accommodate the larger gun, the cockpit was moved farther back along the fuselage. Another variant, the Yak-9K, would mount a 45mm cannon. With this new firepower, even the German Tiger tank was vulnerable.

By September 1943, the city of Smolensk was liberated, an event celebrated with champagne and toasts between Russians and French. Yet, as the Germans retreated, they systematically destroyed the infrastructure of the cities and towns. What had not been destroyed by the Russians in retreat two years before was now ruined by the Germans. Flying overhead, Normandie pilots witnessed hundreds of fires burning where the Germans had evacuated.But the pilots discovered that the new heavy weaponry would slow down their aircraft considerably when fired. They used this to their advantage when landing too fast on a short runway; a short burst of cannon fire would slow their approach.

The Winter Stand-Down

In October, Normandie made its seventh change of airfield. As the front moved ever westward during the Red Army’s relentless advance, the air forces had to keep up. By now the logistics of the move were down to a science. The pilots flew themselves and their mechanics in their own planes while equipment, baggage, and other ground crew members followed in a LI-2. Only two hours elapsed during the move before Normandie was again ready for combat.

By mid-October, mounting losses and decreased effectiveness brought an order from Normandie’s Russian general to temporarily cease operations. During the hiatus, new provisions were flown in as food became more plentiful. Often the pilots’ few luxuries were paid for by well-connected French ladies in the West and flown in. Champagne, wine, chocolates, winter clothing, and other treats arrived in this way.

During the stand-down, the pilots relaxed as best they could. Part of their relaxation included inviting their Russian counterparts to dinner. The 18th Guards Fighter Air Regiment of the Soviet Air Force worked closely with Normandie, sometimes sharing the same airfield and the same patrols. A close bond soon developed between the pilots of both units that would continue until the end of the war.

The lull also brought with it a unit medal. It was the Order of the Liberation (Ordre de la Libération), the second highest French military medal. It had been created by General de Gaulle and only he could approve its recipients. The citation acknowledged Normandie’s 50 victories as well as its 17 lost pilots.

The honors were not over. That same month the Knight of the Legion of Honor (Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur), France’s highest medal, was awarded to Commandant Pouyade and five other pilots of the squadron. The Soviets awarded five of the veterans with the Order of the Red Banner and others with the Order of the Patriotic War, first and second class. These were the first of many honors received by the men of Normandie Squadron.

The stand-down lasted all winter. Like all soldiers, the pilots appreciated their leaves. That meant Moscow and the Savoy Hotel, where they could take an actual warm bath, unavailable at the front. Sometimes their hotel phones would ring and the voice of a young Russian woman would offer to show them around the town. The pilots knew that the young ladies were probably NKVD agents but they didn’t care. Lonely women and lonely men always find a way to get together.

Operation Bagration: The Renewed Russian Offensive

In the spring of 1944, when the city of Alitous in Lithuania was liberated, the pilots often went to Sunday Mass at a local Catholic church. General Zakharov was impressed by the piety of the French until he learned the truth––it was easier to meet girls in church than on the streets.

There were no combat missions until the spring of 1944. There would, however, be extensive training that would last until May. New airplanes, Yak-9s, arrived in numbers. Unfortunately, there was a series of accidents during the training in which several planes were lost or damaged and four pilots were killed. One of them was veteran Lieutenant Marcel Lefevre, who was mortally injured in the crash of his plane. Lefevre was an ace with seven victories (three shared).

Despite the setbacks, by June the squadron was up to full strength and consisted of 47 operational pilots and 61 planes divided into four escadrilles. Organizationally it was now recognized by the Soviets as a regiment.

Shortly after the Normandy invasion on June 6 came the renewed Soviet advance known as Operation Bagration. June 22, 1944, was the third anniversary of the German invasion of the Soviet Union and was the signal for a major Soviet offensive to begin. Hundreds of Red Army planes took part but the Luftwaffe had largely vacated the skies. The Russian advance was so rapid that the supporting airfields were soon far in the rear. Normandie was ordered to move forward once again.

With the growing fame of the squadron, more and more French pilots were volunteering for service and making the arduous journey to Moscow. In over a year of operations, the squadron had amassed an enviable record. Of all the Soviet bombers that it had escorted by Normandie pilots over German territory to date, not one had been lost to enemy fighters.

The Cruel Kapitan Vdovine

By July 1944, the Red Army had reached the Niemen River in eastern Poland and some units of the 3rd Byelorussian Front had crossed the river to form a bridgehead for future operations. Yet here German resistance stiffened. Following their long retreat across the Ukrainian steppes, the beleaguered Wehrmacht troops hastily reorganized and fought back. Air superiority, however, had passed to the Soviets.

Normandie flew constant missions in support of this breech west of the Niemen River, and for their efforts Stalin awarded them the honorary title of “Niemen.” Henceforth, the regiment would be known as Normandie-Niemen.

Around the same time, the Soviet political officer, Lieutenant Kounine, was replaced. Kounine had been quite helpful to the French and was highly esteemed by them. His replacement was a different matter. Kapitan Vdovine was much more devoted to rooting out “wrong thinkers.” He played hell with the Russian mechanics.

All Soviet soldiers had the right to send postage-free letters home. These letters had to be folded a certain way and left unsealed. This allowed censors like Vdovine to read them with ease. The result was a serious decline in morale among the ground crew, and his heavy-handedness was blamed for at least one suicide. This was the case of a pretty 21-year-old Russian woman named Nina who worked as a secretary for the mechanic Agavelian. She had had an affair with a French officer—an act forbidden by the Soviet authorities. When Vdovine found out, he put such pressure on her to end it that she shot herself. The truth was hidden from the pilots but they eventually discovered the reason for her suicide.

On August 1, 1944, Constantin Feldzer was shot down over East Prussia. Captured by the Germans, he managed to avoid being summarily shot by pretending to be a Russian pilot. He was imprisoned by the Germans until March 1945 when he escaped. He was one of only five French pilots out of 25 POWs who survived German captivity.

The Yak-3 vs the German Fighters

By mid-August the squadron surrendered all of its Yaks of different models; they were replaced by 44 brand-new Yak-3s. The most capable of all the Yak variants, the “3” could climb to 35,000 feet and had a top speed of 350 mph. They also were equipped with improved radios so the pilots were able to communicate with new ground-installed radar sites. The Yak-3s were also better dog-fighters than anything the Luftwaffe had at this point in the war.

The nose-mounted gun was reduced to a 20mm cannon to improve stability when firing. There were also two 12.7mm. machine guns firing through the propeller. Of course, like all airplanes, the Yak-3 was not without its faults. It had a limited range, less shielding for the pilot, and, occasionally, a defective landing gear system. Still, it was an impressive machine.

There was more good news in August. On the 24th, the BBC reported that Paris was liberated. The news was celebrated with singing and fireworks by both the French and their Russian friends.Warrant Officer Roland de la Poype (six victories, nine shared), who had flown Hurricanes for the RAF, would later write, “With the Yak-3 we had at last a fighter able to compete with the Fw-190 and Me-109. It was even outclassing them under 4,000 meters where we most often had to fight.…” After four years of the inferior Hurricanes and Yak 1s, the French pilots finally had a superior combat plane.

East Prussia and central Poland now lay open to attack. The Luftwaffe was still strangely absent. A year earlier the Soviets reckoned that 100 German planes a day were shot down; now that number was more like 15. So the Soviet and French flyers focused on ground attacks. Using the nose-mounted cannon, they went out hunting for trains, depots, troop concentrations, road traffic, and river barges. This was not without risk, however, and at least two French pilots were lost while attacking armed trains.

First Combat Group to Occupy German Soil

The Soviet offensive in the summer of 1944, though highly successful, left the supply lines in chaos. Food, fuel, and mail from Moscow were agonizingly slow in reaching the distant front. It took months to receive mail from outside of Russia, which had a depressing effect on the pilots. Lack of aviation fuel slowed the fighters’ efforts to clear the skies and discomfort the enemy. The advance had stalled at the Niemen River and there was little action in September. There was also much frustration among the pilots who had hoped to return home to a liberated France before Christmas.

A touch of good news arrived for 18 veteran pilots who had served with the regiment for over a year––they were offered the opportunity to go home to France. But when the offensive started again, they all elected to stay and fight.

The Soviet juggernaut began once more on October 15, and the offensive into East Prussia was heralded with the advent of a few days of good flying weather. Normandie-Niemen pilots were in the air constantly, attacking the few Fw-190s and Bf-109s that dared rise to challenge them. Otherwise, the air was full of Soviet Pe-2s, Sturmoviks, Airacobras, Bostons, Yaks, and La-5s. The Luftwaffe finally responded by sending up as many planes as it could muster––just what the Soviet and Normandie-Niemen pilots were hoping for.

The day after the offensive began was a banner day for the French regiment. Its pilots downed 29 German aircraft without loss on that single day. The next day they scored nine more kills. One French pilot was shot down, but he was rescued by Soviet ground forces.

There were many more victories for the next two weeks. Even though German industry continued to turn out planes, their newer pilots were less well trained because severe shortages of fuel in Germany limited training flights.

The offensive stalled toward the end of October with a determined German counter-attack and the coming of winter weather, turning November into a time of consolidation and preparation. On the 27th, the regiment occupied a new field inside East Prussia. Of the Western Allies, Normandie-Niemen was the first combat group to occupy German soil. The inaction, though, wore on the veterans. It would be their third winter in Russia. With most of France now liberated, many longed to return home.

201 Enemy Planes Downed in 1944

In December, most of the regiment boarded a train for Moscow where General de Gaulle was on a state visit to see Marshal Stalin. All the pilots were excited to meet the man who had single-handedly redeemed France’s honor. At a special banquet, medals were awarded to the pilots and some Soviet personnel who worked closely with them.

Some of the veterans at last left for home. Their departure prompted the decision to reduce the regiment from four to three escadrilles. The year 1944 ended on a high note: all told, French pilots had shot down 201 enemy planes.

The weather now turned unpredictable, with snow followed by fog or brief moments of clear skies. Sometimes the snow had to be shoveled off a runway before planes could take off. The squadron also received a new commandant: Louis Delfino, who began the war flying for Vichy. He took over operational duties from Pierre Pouyade, who had gone home with 17 other veterans.

New pilots trained when the skies were clear but few missions were flown until January 13, 1945, when the Soviet offensive was resumed. Normandie-Niemen pilots added to their victories but began sustaining increased losses of their own as the fighting intensified.

Striking deeper into East Prussia, the Red Army began liberating French prisoners whom the Germans had put to hard labor. Whenever they could, the French pilots befriended their freed countrymen with gifts of cigarettes and food.

As the number of pilots diminished, there was news that 15 new replacement pilots were in Tehran waiting for transit to Moscow. It was hoped that a new Groupe de Chasse would be formed with the new pilots, but the war would end before this could be accomplished.

Last Battle of the Normandie-Nieman Squadron

The fight for the northern German city of Königsberg would be Normandie-Nieman’s last battle. As the Germans retreated in East Prussia, they gathered in the heavily defended fortress city on the Baltic for a last stand. The 3rd Byelorussian Army, which operated in this sector, unleashed all it had. Waves of bombers dropped tons of ordnance on German positions. Even the DC-3s got into the act as crews manhandled bombs out the side doors. Katyusha rockets sent more tons of explosives into the beleaguered city, and artillery and strafing added to the din, death, and destruction. The French flew protection and hunting missions during this climactic battle.

During the struggle, the French were charged with clearing the skies of the last vestiges of the Luftwaffe. Their new forward base was so close to the front that their runways received incoming fire from German artillery. Pilot Georges Henry (seven victories), who scored the squadron’s last victory on April 12, was killed the same afternoon by a German shell.

Losses during the battle reduced the regiment to two serviceable escadrilles, but even with reduced manpower, they flew all the missions assigned to them. In the end some 42,000 Soviet soldiers and an equal number of Germans died in the rubble of Königsberg.

Return to France

When Königsberg capitulated, Normandie-Niemen could finally stand down. In Berlin, the Germans announced their unconditional surrender. The war was over. More medals were handed out amid jubilant celebrations. Then Stalin himself gave the squadron pilots a unique gift. Forty Yak-3s were presented to the pilots as the Soviet leader’s special thanks for their services, and the men flew home in their planes.

Flying all the way from Moscow to Paris, the pilots were feted with banquets and champagne at every stop along the way. Their faithful Soviet mechanics went with them and shared in a bounty unheard of in their homeland. Reaching Paris in their Yaks in mid-June, the pilots received a heroes’ welcome, and the donated Russian planes would form the nucleus of France’s postwar air force.

It had been a long, hard war for these dedicated pilots. They had endured unimaginable privations: cold, disease, hunger, neglect, and a brutal enemy. Forty-two of their number had been killed. Yet over 30 of them became aces. They had collectively shot down a confirmed 273 enemy aircraft with many more probable, and their combat record of victories was the second highest score in the Soviet Air Force. During their 5,240 missions, they had also destroyed 27 trains, 22 locomotives, two E-boats, 132 trucks, and 24 staff cars, and damaged a number of tanks and armored vehicles.

For France, the accomplishments of Normandie-Niemen were a source of great pride and are remembered to this day by the French people. For many years the Memorial Normandie-Niemen museum was located at Les Andelys in Normandy, but it was closed in 2010 and the collection moved to a new and larger facility at the Le Bourget Airport in Paris (where Charles Lindburgh ended his historic 1927 transatlantic flight) that will open in 2012. The director of this new museum is Girard Feldzer, the nephew of Normandie-Niemen pilot Constantin Feldzer.

Hi

This is a great article – thank you.

I am rebuilding a YAK 7 B in New Zealand. The aircraft was purchased in the USA 2 years ago and is undergoing very extensive restoration work. I was planning to have it painted to honour ace Marcel Albert but I have discovered there is a YAK 3 in France, recently returned to flying status, painted as his aircraft. I am researching an alternate Normandie-Niemen squadron ace to honour. Do you have any suggestions ?

Regards

Mike

I love stories like these! It is nice to read about some of the lesser-known but no less fascinating episodes of WW2. Keep up the good work.