By Blaine Taylor

In September 1948, Lt. Gen. Walton Harris Walker, 58, took over command of the Eighth Army on occupation duty in Japan from his predecessor, Robert Eichelberger, a former West Point superintendent and devotee of Allied Supreme Commander General Douglas MacArthur. The belligerent-looking Walker’s four-division command comprised the U.S. Army’s understrength 1st Cavalry and 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions (“Tropic Lightning”). Noted his then-chief of staff, Colonel Eugene M. Landrum, the general had come to Japan “anticipating a nice, cushy time, beautiful quarters and easy duty” before his eventual retirement. He had earned it, having fought during the Mexican Expedition against bandit Pancho Villa, the Germans in World War I, and the Germans again in World War II as part of the Third Army of his mentor, General George S. Patton, Jr.

Then came the lightning strike across the 38th Parallel dividing North and South Korea by the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA) that launched a fierce drive on June 25, 1950, to oust American forces, destroy the South Korean Army, take the capital of Seoul, and unite the twin Koreas under the single Communist rule of dictator Kim Il Sung.

A wholesale rout began, despite desperate fighting, leading Francesca, the wife of South Korean President Syngman Rhee, to write on July 14 that the Americans “are good in the air, but have no tactics on land. They only retreat.… The Americans are no match for the heavy tanks and tactics of the Reds. The North Koreans openly say that the Americans cannot fight on land because they do not want to die.”

In the GI parlance of the time, the retreating troops “hauled ass,” abandoning their weapons as they did so. One soldier later recalled in Stanley Weintraub’s excellent MacArthur’s War, “We were sent over there to delay the North Koreans—we delayed them seven hours.”

Clearly something had to be done, and quickly. MacArthur, after a flying visit to a hillside outside Seoul, decided on the spot to commit the entire Eighth Army of Walker’s command to save the South Korean port city of Pusan. Thus the famous Pusan Perimeter concept at the southern tip of the Korean peninsula was born. In MacArthur’s mind, if Walker could hold on there, MacArthur would launch a daring side counterstroke at Inchon from the sea that would cut off the NKPA from behind and strangle its supply lines. Then he and Walker together could crush the enemy like a walnut.

For the operation to succeed, however, all depended on Walker’s ability to hold his ground. The questions were: Could and would he do it?

Who was this “bulldog” that MacArthur entrusted with so important a mission?

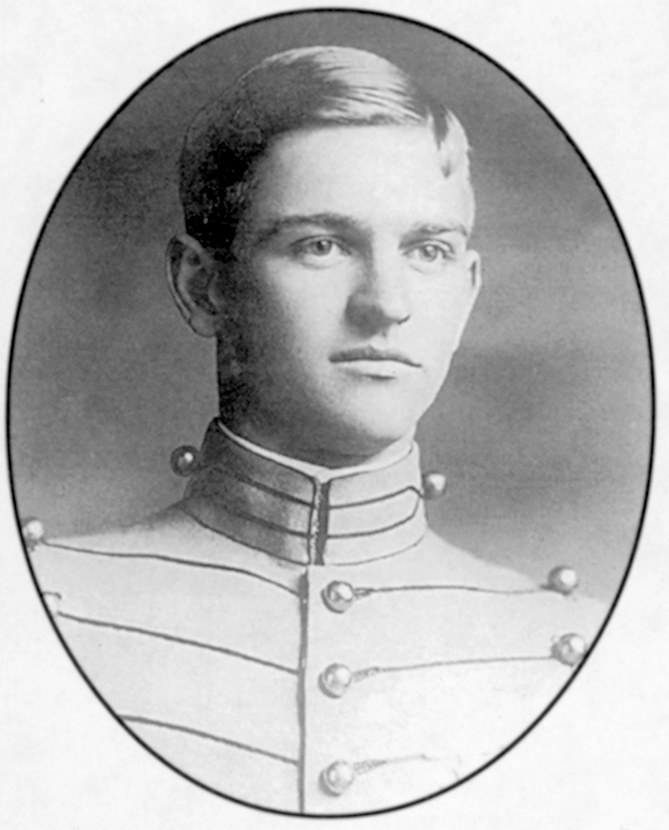

Walton Walker was born on December 3, 1889, at Belton, Tex., and entered the renowned Virginia Military Institute in 1907, transferring as a plebe to West Point the following year. He graduated in 1912 with an infantry commission and participated in the naval occupation of the port city of Vera Cruz in Mexico. In 1916, he met Lieutenant Dwight D. Eisenhower while serving in the same regiment along the Mexican border, and they became both close friends and fellow hunters.

In World War I, as a member of the American Expeditionary Force in France, Walker served with the 13th Machine Gun Battalion of the 5th Division and fought in the battles of St. Mihiel and the Meuse-Argonne. Awarded a Silver Star—second in rank only to the Medal of Honor—Walker was promoted to colonel during the occupation of the former defeated Imperial Germany.

He returned to the United States late in 1919 and reverted to his permanent rank of captain. He was posted as an instructor, first to the Infantry School at Ft. Benning, Ga., and later the Coast Artillery School at Ft. Monroe, Va., before being assigned during 1930-1933 to the 15th Infantry in Tientsin, China. Following his reposting to Washington, DC, he served during 1937-1940 on the Army Staff in the War Plans Division, which brought him to the notice of the future Chief of Staff (appointed September 1, 1939), General George C. Marshall.

Walker’s first World War II command was the 3rd Armored Division with the rank of major general. In September 1942, he took over the IV Armored Corps, which was redesignated XX Corps in August 1943, and the following February he was sent to England to prepare for Third Army’s invasion of the Continent under the leadership of Patton that July. The two men were about to make military history.

The drive across northwestern Europe established their joint reputation as well as that of “Lucky Forward” in martial annals. Walker’s own XX Corps became known as the “Ghost Corps,” much as had Erwin Rommel’s 7th Panzer been renowned as the “Ghost Division” four years earlier for its rapid rate of movement.

During the Battle of the Bulge, when Patton had to wheel most of Third Army north in a race to relieve American forces at German-encircled Bastogne, it was Walker’s task to cover all of Third Army’s former front, which he did ably, ending the war with his third star and the high praise of both Patton (no mean feat) and Ike, who called him “a fighter in every sense of the word.”

Like Patton, General Walker put on a manly Mussolinian scowl for the photographers’ lens, and was known as a tough, aggressive, no-nonsense soldier—just the sort of man that MacArthur needed to hold the 140-mile-long Pusan Perimeter. Like the late General Patton (who died as a result of a freak automobile accident), Walker was a man who carefully polished his image, both for the troops and the media. Notes historian Stanley Weintraub, “Walker’s lacquered helmet gleamed and his command vehicles were trim and shiny. His personal jeep displayed black leather seats, and a machine gun mounted in the rear, with attendant gunner. Walker sat in front next to the driver, and brandished a .45 automatic and a repeating shotgun. ‘I don’t mind being shot at,’ he said, ‘but these bastards aren’t going to ambush me.’”

When he met with the 25th’s divisional commander, Maj. Gen. William F. Dean, and his staff, he articulated what would become his oft-repeated mantra to all the men under his command: “There will be no more retreating, withdrawal, or readjustment of the lines or any other term you choose. There is no line behind us to which we can retreat. Every unit must counterattack to keep the enemy in a state of confusion and off balance. There will be no Dunkirk, there will be no Bataan and a retreat to Pusan would be one of the greatest butcheries in history. We must fight to the end.… If we must die, we will die fighting together. Any man who gives ground may be personally responsible for the death of thousands of his comrades.”

Truly, this was the kind of man New Orleans found in the person of Andrew Jackson in 1815—a winner who could and did inspire both his subordinates and troops to victory in the face of daunting odds.

Meanwhile, preparations went ahead with MacArthur’s planned Inchon attack. As MacArthur noted in his 1964 memoirs, Reminiscences, “The month of August in Korea witnessed repeated and savage attacks on our forces, but the South Koreans had now been rallied and reorganized, and five small Republic of Korea divisions—the 1st, 3rd, 6th, 8th and Capital—were with Gen. Walker. A brigade of the 1st United States Marine Division had also joined the Eighth Army.” (The Marine division was later withdrawn for use in the Inchon landing.)

The bulk of the Red forces were now centered on battering the perimeter into either surrender or destruction—whichever came first. Evacuation by sea was not an option, but the enemy didn’t know that. MacArthur was the Allied Supreme Commander and commanded both the Eighth Army and the XX Corps for Inchon from his Tokyo headquarters. The distance and arrangement oftentimes created both organizational and tactical problems for the man in the field—“Bulldog Johnny” Walker, but Walker soldiered on, shoulder to the wheel.

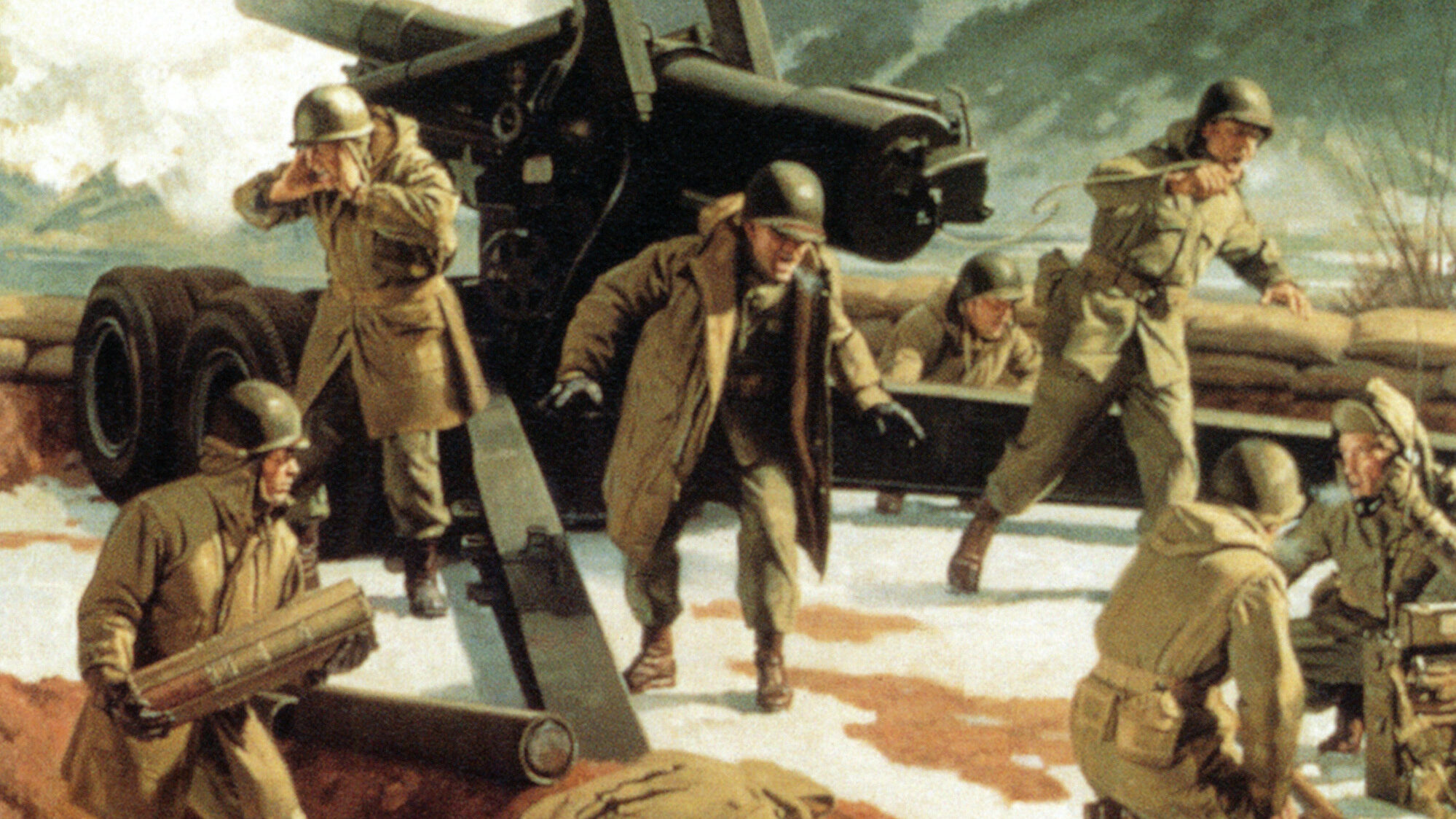

As approved by President Rhee on July 17, 1950, Walker had been made overall UN commander in the perimeter, where he called in both U.S. Navy warship gunfire and carrier-based aircraft strikes to support his beleaguered ground forces against the attacking NKPA. When British Commonwealth troops arrived on the scene to reinforce him, Walker sent these men straight into combat, as he also did other infantry and tank units as they came on line. The perimeter held—barely.

Already, on the 14th, The New York Times had called his efforts “one of the most skillful and heroic holding and rearguard actions in history,” with 20:1 numbers against him on the ground. Then MacArthur struck at Inchon, and the whole course of the war was altered in a single thunderclap, just as MacArthur had predicted it would be.

“Every soldier will retain his weapon, ammunition and entrenching tool,” Walker had previously trumpeted to his embattled legions, and now these were used with devastating effect as the Eighth Army drove to link up with XX Corps moving inland from Inchon. With both Pusan Harbor safe and the additional port of Wonsan in UN hands, resupply was no longer an issue. Juncture with XX Corps occurred on September 26.

The Eighth Army rolled the NKPA northward in a sweeping juggernaut that crossed into North Korea and took its capital city of Pyongyang on October 19. Victory, it seemed, was complete, but MacArthur, according to his later critics, wanted then to go a war better: Cross the Yalu River in force, invade Communist Red China, topple its dictator Mao Zedong, and restore to power his friend and ally, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek.

MacArthur’s “final offensive” to end the war by Christmas was launched on November 24. But the Chicoms (as the Chinese Communists were then called) attacked in force the next day, led by the twin armies of, first, Marshal Peng Teh-huai and, second, field generals Sung Shih-lun and the future Marshal Lin Piao (who would die decades later in a failed plot to overthrow Mao himself).

Now the war was reversed strategically yet again, with all the previous UN gains lost as the forces of Walker and MacArthur were driven back down into South Korea toward Pusan. Would there be a second battle for a renewed perimeter, this time without a masterful Inchon surprise attack to offset it?

It well looked like World War III might actually begin in Korea to stave off a UN bloodbath. On December 3, 1950, President Harry S. Truman approved a joint MacArthur/Walker consolidation of their forces into fortified beachheads. Walker, the man who in September had said that “If the enemy gets into Taegu, you will find me resisting him in the streets and I’ll have some of my trusted people with me and you had better be prepared to do likewise,” found himself in the same situation again. Then as before, he had said, “I don’t want to see you back from the front again unless it’s in your coffin.”

Ironically, he was in his own coffin first. On the morning of December 23, the general stepped into his personal jeep for a trip from his headquarters in Seoul to I Corps, roughly 20 miles to the north in Uijjongbu. With him was his customary driver Master Sgt. George Belton, who had driven him in France and Germany. At Uijjongbu, Walker was to present Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citations to the 24th Division and the British 27th Brigade.

On each fender of the jeep were sirens and flashing lights, the better to speed the jeep past congestion. Walker wore a pile-lined cap with earflaps and a rug across his lap to thwart the cold. Nearby was a handrail welded to the jeep body so he could stand when he wanted to.

Nearly all the traffic was in the opposite direction—south—because the capital was being moved to Pusan during the emergency. South Korean 6th Division trucks and jeeps crowded the highway. Suddenly, in Weintraub’s description, “an ROK weapons carrier clipped the left rear of the speeding jeep, which hurtled off the icy road and turned over. Walker and his driver were killed instantly.”

Walton Walker was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors on January 2, 1951, and was posthumously promoted to full four-star general by President Truman. He became the country’s first authentic Korean War hero. Although MacArthur had never fully appreciated Walker’s generalship in life and had denied him command of the XX Corps joined to his own Eighth Army, the Supreme Commander wrote in Reminiscences that Walker’s death “was a great personal loss to me.” This is not a bad epitaph for a man who had served under two such prima donnas as MacArthur and Patton. n

Towson, Md., freelancer Blaine Taylor is the author of a trio of books on World War II as well as the forthcoming Volkswagen Civil and Military Vehicles of the Third Reich.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments