By John E. Spindler

At dusk on August 24, 1944, south of Paris, about half a mile from Croix de Berny crossroads, stood a tall, lanky man tapping a malacca cane. Maj. Gen. Philippe Leclerc, commander of the French 2nd Armored Division, or 2eme Division Blindée (2e DB) in French, had expected to have his division in Paris by now.

However, the Germans had not cooperated, and he had lost precious time fighting through their defenses. The strongpoints centered around a flak battery employing the deadly German 88mm antiaircraft/anti-armor gun. Situated at Croix de Berny, this German strongpoint was part of a defensive area guarding the primary route into southern Paris. As a result, units of the 2e DB were over 10 miles from their ultimate objective—the liberation of Paris.

Leclerc resigned himself to the fact the 2e DB would not be celebrating the night in the capital. Not only had his men fought for hours, but they had spent the previous day in a mad dash to Rambouillet, 22 miles from the southwestern edge of Paris. Around 7:30pm, the general spotted Captain Raymond Dronne.

A veteran who had served Leclerc since the Free French was formed in 1940, Dronne was also frustrated. He firmly believed the road to Paris was within reach via lesser paths. Failing to convince his immediate superior of this, he had been ordered back to the main effort. Summoned by Leclerc, he explained his situation, to which the general replied, “Dronne, don’t you know enough not to obey stupid orders?”

Leclerc told him to find a way into Paris, take whatever he could get his hands on, and avoid confrontations. Dronne had two platoons of infantry with him, but knew stronger support was needed; with a little persuasion he soon had three Sherman tanks and a platoon of engineers join his impromptu detachment. Twenty minutes later Dronne’s force, consisting of the three Shermans and 150 men in 15 half-tracks, was on its way.

With the assistance of a guide, Dronne’s group took back roads and made their way for Port d’Italie. Upon entering the city, this force was mistaken first for Germans, then for Americans by civilians and resistance fighters of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). When the Parisians learned these men were French, they went crazy. After a brief stop to assess the situation, Dronne drove to the Hôtel de Ville—city hall—which was headquarters for the French Resistance forces.

At 9:22pm, the group arrived outside the Hôtel de Ville, slowed only by jubilant crowds. Announcing that the rest of the division would be in Paris tomorrow, he set up a defensive perimeter. Feeling their ordeal was at an end, Parisians began to sing France’s anthem, “Les Marseillaise.”

Recently liberated French Radio announced the Leclerc Division had entered Paris. Power was turned back on to allow everyone to know freedom was at hand.

Shortly after the news of Dronne’s arrival spread, church bells rang across the city, beginning with Notre-Dame Cathedral. For the first time since the black day of June 14, 1940, when the Germans entered their city did Parisians hear this sound.

The downfall of France’s Third Republic had begun with Germany’s invasion of the Low Countries on May 10, 1940. Despite warnings from Polish soldiers-in-exile, the German blitzkrieg tactic took the French and British by surprise. Although there were islands of resistance, Paris was declared an open city on June 12. Ten days later the new French leader, Marshal Philippe Petain, surrendered and signed the armistice. He became the head of Germany’s puppet government in Vichy, France.

It was during May 1940 that an obscure officer named Colonel Charles de Gaulle, commanding a tank regiment in Alsace-Lorraine, became an inspiring leader. When Germany invaded, de Gaulle, in under two weeks, earned a battlefield promotion to brigadier general. Shortly after the Dunkirk evacuations, he was appointed to a position in the French cabinet by Prime Minister Paul Reynaud.

Sensing France’s imminent defeat on the battlefield, Reynaud sent de Gaulle to London to obtain assistance from Prime Minister Winston Churchill for the relocation of the French government to French North Africa. Churchill recognized de Gaulle as leader of the Free French, and within weeks an agreement was reached between the two. However, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt felt Petain and the Vichy represented the future of France, and only grudgingly accepted de Gaulle in the summer of 1944.

Among those who supported de Gaulle was Captain Philippe de Hauteclocque. After escaping to Britain in 1940, he adopted a nom de guerre to protect his family back home. Choosing “Leclerc,” his personal traits and colonial experience resulted in rapid promotions. Soon Leclerc was on his way to Equatorial Africa and achieved miracles, considering the number of troops and materials available to him.

Over the next few years, Leclerc’s forces made major raids into Italian-controlled Libya. He wore the rank of two-star general when his forces linked up with the British Eighth Army in January 1943. Assisting in the Allied victory in Africa, Leclerc’s “L Force” remained and grew to division size.

In August 1943, it became the 2eme Division Blindée—fully outfitted and equipped by the United States, with the provision that it be organized according to American armored division standards. General de Gaulle’s desire to have at least one French division for future operations in northern France ensured the division would be shipped to Britain in April 1944 for the planned liberation of Europe.

While de Gaulle and Leclerc were fighting to free France from the outside, bands of resistance opposed to the Germans and their Vichy underlings formed as early as fall 1940. Throughout 1942 and 1943 de Gaulle attempted to bring the numerous resistance groups into a unified command answering to him with limited success. He feared the communist resistance movements as much as he feared the Germans.

In Paris, communist Henri Tanguay became the leader of the resistance movement under the code name “Colonel Rol.” He believed that it was crucial for Parisians to liberate their city and was ready to ignore de Gaulle’s demand of no insurrection. There were an estimated 35,000 FFI members but only 570 rifles and 820 revolvers, which limited the possibilities for revolt.

Due to his fear of the communists, de Gaulle dispatched his own men—General Jacques Delmas (codename “Chaban”) as military representative and Alexandre Parodi as political representative—to Paris to counter Rol’s influence. De Gaulle was keen to prevent an early uprising, as he feared it would not be successful.

In terms of German governors, Paris had been generally better off than many other occupied areas. Commander of the Paris region, General Hans von Boineburg-Lengsfeld, had one of the easiest administration assignments. Though the Parisians had to deal with fuel shortages and a worsening scarcity of food, he rarely employed the strict occupation measures found in many areas the Germans controlled.

Boineburg’s tolerant administration was interrupted in March 1944, when the German defense plans, in effect since the 1942 Dieppe raid, were examined and found inadequate. He was ordered to revise them with the inclusion of a scorched-earth policy for Paris in case of an enemy attack. The situation unraveled further for Boineburg on June 6, 1944, when the Allies’ Normandy landings changed everything.

Return to France

Leclerc’s division was assigned to U.S. Third Army under Lt. Gen. George Patton. Landing after the rest of the Third Army, the 2e DB arrived on French soil the first week of August 1944. Patton’s divisions had already overrun Brittany and then turned eastward.

Leclerc’s division of 14,500 was an amalgamation of forces he’d led across Africa— veterans, escapees from France, North Africans, Christian Arabs, and Spanish Republicans. The power of the division was its three armored regiments—the 501eme Regiment de Chars de Combat, the 12eme Regiment de Chasseurs d’Afrique, and the 12eme Regiment de Cuirassiers. All regiments used American-built M4A2 Sherman medium tanks.

Supplementing the armor was the infantry, the Regiment de Marche du Tchad, consisting of three battalions. The division’s tank-destroyer regiment, the Regiment Blindée de Fusiliers-Marins, used American M10 tank destroyers in which the standard optical range finders had been replaced with superior naval optics. Rounding out the division was a reconnaissance regiment, three artillery groups, engineers, anti-aircraft, supply, signals, motor transport, and three medical companies.

Soon after arrival, Leclerc was assigned to the U.S. XV Corps. Leclerc organized his division into three tactical groups (GT, from Groupement Tactique): GT D (Dio), GT L (Langlade), and GT V (Billotte). Each GT was made up of an armored regiment supported by infantry, artillery, reconnaissance, and tank-destroyer elements.

From August 8 to 12, the 2e DB saw its first major action in liberating Alençon, then helped close the Falaise Gap in a drive to Argentan. Leclerc demonstrated that he would do anything to attain his goals, even if it meant going against orders from his superiors.

At Argentan, Leclerc, de Gaulle, and Haislip appealed to Eisenhower to allow the 2e DB to drive on Paris; Ike had promised that the French division was going to be the first into the capital. However, the situation had changed along the Seine, leading Eisenhower to decide that Paris would be bypassed in pursuit of the Germans.

In early August General Dietrich von Choltitz was called to Hitler’s headquarters as Boineburg’s replacement. At the time he was commanding the German LXXXIV Army Corps in Normandy. During Operation Barbarossa, he led a unit in the German Eleventh Army that fought in the siege of Sevastopol. By the time the battle was concluded, his unit had less than 10 percent of its men left. As the war progressed, Choltitz rose in rank and received larger units to command. On August 1, he was promoted to General of the Infantry. Six days later he was named Befehlshaber—fortress commander—of Greater Paris, with even more powers than Boineburg had possessed.

On his way to meet Hitler at Rastenburg, East Prussia, on August 8, 1944, Choltitz heard of a new law enacted in the Reich—Sippenhaft. Surrendering or unable to attain assigned objectives needed to be punished. In order to maintain faithfulness, under Sippenhaft the families of high-ranking officers would be held responsible for the failures of said officers.

Choltitz’s morale was suffering from the string of German defeats, and he left the meeting believing that Hitler was delusional and a shell of the man he had met in 1943. He was told to be ruthless and stamp out any acts of aggression against German forces in Paris.

Thoroughly demoralized, Choltitz was convinced Hitler and his staff had no grasp of the military situation in France. After the meeting, Hitler’s chief of the General Staff handed Choltitz his orders and range of powers, which, in addition to control of the armed forces, included the police and many German government departments. Spending the night with his family, he proceeded to his new appointment, arriving on August 9.

Choltitz spent the next few days with Boineburg, going over the defensive plans the latter had created and begun to put into effect. Boineburg had General Humbertus von Aulock establish a defensive perimeter outside city limits covering the western to southern approaches. Choltitz and Boineburg agreed that there was no military value in defending the capital. Notes taken during the meeting indicate that Choltitz had made up his mind not to turn the city into rubble.

Soon after taking command, he held a military parade to show Parisians that the city was still under German control and that minor acts of sabotage and civil unrest would cease. He issued orders to have the city’s police force disarmed as a precautionary measure. After Patton’s Third Army’s breakout, Choltitz reviewed the defensive resources he had at his disposal and ordered the administrative personnel to evacuate the city.

About 20,000 troops garrisoned the greater Paris area, spanning a wide range of military quality. The heart of the defense was the 325th Sicherungs Division (325th Security Division). Due to the Allied drive, two of its four regiments had been dispatched to Chartres on August 15, which left 5,000 soldiers in the city.

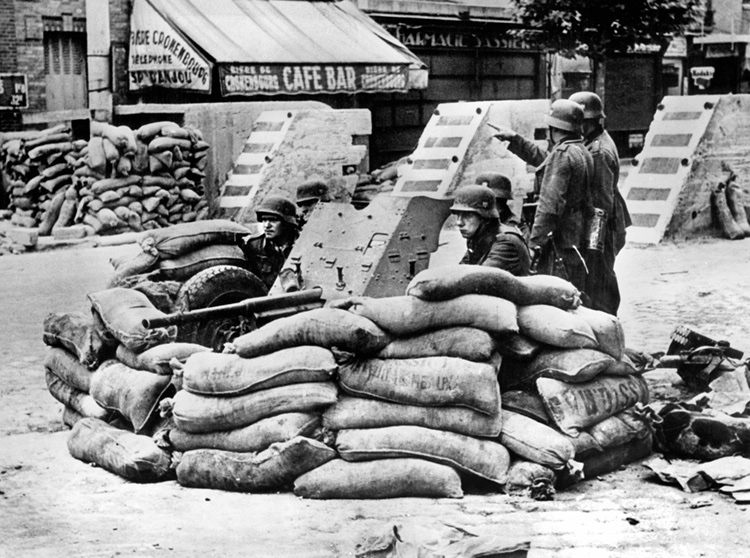

Some veteran units existed, but the majority of Aulock’s soldiers were mere teenagers, drafted to perform garrison duty or man the flak guns. Choltitz kept his predecessor’s plan of the defensive line guarding the western and southern approaches. Paris had never been bombed by the Allies; thus, the anti-aircraft artillery of the Luftwaffe’s 1st Flak Brigade would best be used as ground support and became the core of the Boineburg Line.

Apart from the flak guns, little artillery was available to the German defenders. In terms of armor, the situation was dire. A panzer company was formed from 13 obsolete tanks, the majority of which were French-built. Only three PanzerkampfwagenV, better known as the Panther, were in the city. The Luftwaffe was also non-existent, especially after August 17, when the two remaining fighter groups were withdrawn.

Another crucial figure during this period was Swedish Consul Raoul Nordling. Nordling was aware of atrocities in French cities that had been lost by the Germans. Having heard the Germans were emptying the Paris detention facilities and loading the prisoners on trains bound for Germany, Nordling, along with a German intelligence officer named Emil “Bobby” Bender, visited Choltitz at his headquarters in the Hotel Meurice. Nordling requested that, since the Germans were evacuating the city, as a gesture Choltitz should allow the release of all political prisoners. Choltitz agreed, and numerous lives were saved by not being sent to Germany.

During this same period, an outline for a limited scorched-earth policy was presented to Choltitz. The systematic destruction of the utilities, including water, gas, electrical, and telephone,was to be implemented in conjunction with the demolition of select industrial complexes. A team of engineers arrived with orders to bring down all the Seine River bridges.

Though Choltitz accepted the plans, he objected to their timing. He told his superiors that it was not just the French who needed water, but also the thousands of remaining Germans. And, as the Parisian bridges were the only ones that had not been destroyed by the Allies, they were needed to move troops to and from the battlefront.

On August 15, the same day that Allied forces landed in southern France (Operation Dragoon), the Paris police went on strike but kept their weapons. This would be crucial for the future of the uprising due to the acute shortage of firearms in the Resistance.

Choltitz took no further action. He reasoned it was better to have the police politically neutral rather than pushed into the Resistance. He also met with Germany’s new Commander-in-Chief for the West, Field Marshal Walter Model, who relayed orders that Paris and the Seine River must be held at all costs.

The next day, employees of the telephone and telegraph company, Paris Metro (the subway), and railroads went on strike, followed by a postal strike on August 17. Momentum gathered when workers from various occupations across Paris brought about a general strike the next day.

Due to his not-entirely-baseless fears of the communists taking control, de Gaulle sent Charles Luizet to take command of the Paris police. Luizet arrived on August 17, with the police already on strike. He met with Parodi and Chaban to discuss the situation and Parodi told the others of the communist plan to initiate a revolt. Action needed to be taken or else Rol and non-Gaullists would gain control of the insurrection.

The Battles Begin

Early on the morning of August 19, hundreds of policemen answered a call issued by Parodi and marched on the Prefecture of Police building across from Notre-Dame Cathedral. Encountering little resistance, they secured it. For the first time in four years, two months, and four days, the French Tricolor officially flew from a public building.

In an emergency meeting of the CNR to discuss plans, the Resistance leaders were presented with a fait accompli by the Gaullists. The FFI moved to take over other key public buildings throughout the Paris metropolitan area, including the Grand Palais and the Hôtel de Ville, which was given to the leadership of the CNR.

Choltitz and his staff were caught completely off guard, as intel had not suggested an imminent, large-scale insurrection. By mid-day, he had ordered the forceful retaking of the Prefecture. The infantry would be supported by an obsolete French-built R-35 tank and a pair of Panthers.

A fierce battle for the Prefecture began. Although the defenders were able to destroy one of the tanks via Molotov cocktail, it became apparent there simply was insufficient ammunition and other supplies to withstand the siege.

Consul Nordling hurriedly met with General Choltitz and suggested a temporary cease-fire for both sides to collect their dead and wounded. After thinking it over, Choltitz agreed, but stipulated that his name was not used in enacting the cease-fire. He did not want word to get back to Germany, fearing the Sippenhaft would be used to punish his family.

General Leclerc’s division was transferred to Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ U.S. First Army and placed into the U.S. V Corps under Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow. After learning of the start of the insurrection, Leclerc requested that his division be sent to Paris but was rebuffed by Gerow. He told Leclerc that the destruction of the German armed forces’ ability to wage war was more critical than liberating Paris.

In Paris the next day, August 20, the tenuous cease-fire went into effect. It only lasted a couple of days, during which there were incidents initiated by both French and Germans who preferred to ignore it. While police at the Prefecture were able to enjoy a respite, Colonel Rol dispatched his chief of staff, Roger Gallois, to take a message to the Americans requesting arms and ammunition for the Paris Resistance.

In the Allied camp, de Gaulle arrived in France and met with Eisenhower. De Gaulle presented his case that he and the 2e DB needed to be in Paris. Though Eisenhower had high regard for de Gaulle’s judgment, he stated the Allied plans could not be altered; De Gaulle said that he would simply take his division back. Ike replied that the division relied on U.S. supplies, which would cease if de Gaulle acted on his threat.

Unbeknownst to the Americans, Leclerc had been under-reporting his losses; therefore, the 2e DB continued to receive supplies, especially ammunition and fuel, for a greater number of men and vehicles than it actually had.

German engineers began preparing certain structures for demolition, as Choltitz continued to procrastinate in obeying the order. He even refused to see the captain in charge of the engineers—the first time in his 29-year military career that he was insubordinate.

On the Paris streets, Germans used human shields on their vehicles to counter the Molotov cocktails. The crude explosive had already knocked out a number of German vehicles.

Though Parodi reluctantly voted to end the cease-fire, he had used the time to ensure that the Gaullists gained power in the liberation of Paris. Colonel Rol tried to reassert the communists by using the Paris tradition of constructing barricades at key places throughout the city. Suddenly, barricades made of felled trees, damaged automobiles, and cobblestones began to appear.

Colonel Rol’s chief of staff, Roger Gallois, managed to reach the American line and met with General Patton, who was not in favor of an Allied drive on Paris but sent the Frenchman to see his superiors.

Leclerc, on orders from de Gaulle, sent a reconnaissance in force towards Paris. The lieutenant commanding the force was under orders to “avoid Americans.” Ready to follow were another 2,000 vehicles and 14,000 men. De Gaulle drafted a pair of letters, one to Eisenhower asking permission to move on Paris and one to Leclerc to be ready to advance.

Liberation

August 22 turned out to be a pivotal day for Parisians. The city saw the heaviest fighting since the onset of the insurrection. General Eisenhower drafted a letter to the U.S. Combined Chiefs of Staff justifying a military move into Paris by stressing that the city had the potential to become “a constant menace in our flank.” Bradley set off to inform Hodges of the new plans to take Paris, after which he flew to the city of Laval and met with Leclerc.

Leclerc was on his way to plead with Bradley regarding his confrontation with Gerow. Gerow had learned of Leclerc’s force sent to Paris and ordered the French general to recall it to the Argentan area. Bradley informed Leclerc of the new plan, and that his division was to lead the charge with the only stipulation being no heavy fighting in the city.

That night Leclerc returned to Argentan and informed his group commanders of the good news. Although ordered by Gerow to start that night, Leclerc decided to set off the next morning. He calculated it would take two days to cover the 122 miles to the French capital. What Bradley chose not to share with Leclerc at that time was that he was also sending the veteran U.S. 4th Infantry Division.

At the Hotel Meurice, Choltitz and Nordling met again. When the German told Nordling the ceasefire was not working, Nordling replied the FFI would only listen to one person—Charles de Gaulle. Choltitz suggested that Nordling cross lines and meet with him to explain the situation in Paris. He provided the Swedish consul with a pass to get through German lines. Unfortunately, the frantic situation of the past few days caused Nordling a mild heart attack, which forced the consul to send his brother Rolf on his behalf.

At dawn on August 23, the two 13-mile-long columns of the 2e DB began their drive on Paris. Meanwhile, after sniper fire came from somewhere near the Grand Palais, German return fire set hay for a circus inside the building ablaze, causing serious damage. The Germans also killed small groups of Resistance fighters as they encountered them throughout the city.

At midday, the telephone exchange for the Western Front was blown up. The engineers had finished setting charges on the Seine bridges, as well as at monuments and municipal buildings. All that was needed was for Choltitz to give the order.

Rolf Nordling met with Bradley and informed him that Choltitz had orders from Hitler to destroy the capital. Bradley was doing his best to delay that outcome, but was getting backed into a corner. The Swede pleaded that the Americans must liberate Paris before Choltitz was forced to carry out Hitler’s insane orders.

Leclerc’s division was only able to travel as far as the town of Rambouillet, 27 miles southwest of Paris. His exhausted men needed rest if they were to fulfill the promise Leclerc had made while in the Libyan desert to free Paris. De Gaulle then arrived and met with him.

With de Gaulle’s approval, Leclerc decided to enter Paris from two directions: GT L was to enter from Porte St. Cloud on the southwest edge, while GT V would enter from the south via Porte d’Orleans. Once in the city, the goal was to drive to the heart of Paris. The situation became complicated when that night the BBC announced that Paris had been liberated.

After getting a few hours of much-needed rest, the 2e DB commenced its drive on Paris at 6:30am on a rainy August 24. In addition to the main battle group assignments, GT D was to advance behind GT V, while a small diversionary force took the road via Versailles with orders to make as much commotion as possible to deceive the Germans into believing this was going to be the main axis of assault.

In English ports, tons of medical supplies and thousands of tons of food were being assembled for delivery to Paris. To the dismay of both the American 12th and British 21st Army Groups, they were required to relinquish much-needed trucks to help with hauling the emergency supplies.

In contrast to the all-out drive on the previous day, the men of 2e DB made significantly less progress as they entered an urbanized area covered by the dreaded 88mm cannons. Additionally, spontaneous celebrations of newly liberated French citizens caused delays.

GT L, under Colonel Paul de Langlade, entered the city from the southwest via Villacoublay and its nearby airbase. At first, progress went well, and GT L divided into two sub-groups as planned. Suddenly, they struck the Boineburg Line, and the defenders knocked out the lead Shermans. Throughout the day, the two sub-groups struggled to fight their way through the tough defenses.

The Regiment de Marche du Tchad had been divided between the three task forces, which meant there was a scarcity of infantry for overcoming the defensive positions. Suppressing them required time to outmaneuver and attack from the flanks or rear. By nightfall, the diversionary group rejoined Langlade’s men, who had secured the Sevres Bridge over the Seine. However, they were still a couple of miles from Porte Saint-Cloud.

To the south, Colonel Paul Billotte’s GT V also had smooth advance until it struck the Boineburg Line. As with GT L, Billotte divided his force into two sub-groups while driving north. They spent the majority of the day eliminating the aforementioned strongpoint centered around the Fresnes Prison and Croix de Berny crossroads, where they stopped for the night, 13 miles from Porte d’Orleans.

In the afternoon, Leclerc dispatched a Piper Cub that flew over Paris and dropped a message to the population that read Tenez bon. Nous arrivons. (“Hang on. We’re coming.”)

Leclerc was not the only one frustrated when his division was unable to advance into Paris; so was Gerow. He was unaware that Aulock’s defensive barrier was stronger than originally thought and complained to Bradley about the French division’s slow progress. Bradley had Gerow order the U.S. 4th Infantry Division to outflank the French and enter Paris.

That evening Leclerc sent Captain Dronne on his celebrated dash into the heart of Paris. After 1,532 days, the French Army had returned to the French capital.

The next day, August 25, which was the Feast of Saint-Louis, patron saint of France, saw Paris liberated. Aulock had his surviving troops join Model’s units east of the capital. Choltitz still had a considerable number of troops inside Paris, but ordered them to remain at their strongpoints.

A note demanding surrender was sent to Choltitz. Saying it was too soon, he refused it. Around 1:00pm, the coordinated assault for the final push commenced. Its goal was to capture Choltitz and eliminate the German strongpoints. To capture the Hotel Meurice, a detachment of Shermans from the 501eme Regiment de Chars de Combat, accompanied by some infantry, was dispatched.

Back at his headquarters, Hitler heard of the French attack on Paris and went into a rant. According to some sources, he bellowed his famous line, “Brennt Paris?” (“Is Paris Burning?”)

The armor and infantry detachments fought their way into the Hotel Meurice and, shortly after 2:00pm, a small squad went up to General Choltitz’s floor. The group’s leader asked if the general spoke French, to which Choltitz replied, “Probably better than you do.” Moments later, the lead officer for the operation arrived and asked if Choltitz would now surrender. Having fought his symbolic battle, he and his staff surrendered.

After arriving at Leclerc’s headquarters, the two generals discussed surrender terms. As part of the agreement, all German strongpoints were to surrender. To each of these locations, representatives were sent bearing a copy of Choltitz’s surrender order. At 4:15pm, de Gaulle arrived in Paris from Rambouillet and made his way to the Hôtel de Ville. On the way, he was greeted by Parodi. During this time, the remaining strongpoints obeyed the orders from Choltitz and gave up their arms. The SS garrison at the Palais du Luxembourg was the last to surrender at 7:35pm, and only after the soldiers had expended all of their ammunition. Paris was finally free.

In the streets, French and American soldiers handed out whatever food they had to the population. That night, the first since France declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939, the lights of Paris were turned on to their full extent.

De Gaulle arranged for a parade at 3:00pm the next day down the Champs-Élysées starting at the Arc d’Triomphe, to end with mass at Notre-Dame Cathedral. Proceeded by four of Leclerc’s Shermans, de Gaulle marched down the Champs-Élysées, followed by his leading generals, leaders of the Paris Resistance, and members of his government. In his memoirs, de Gaulle estimated that almost two million people turned out to watch a parade that was not without a potential for disaster. Snipers remained, and an air raid could inflict a significant number of casualties.

All went well as de Gaulle was cheered by jubilant Parisians until the group passed by the Place de la Concorde. Suddenly, shots rang out. Everyone took cover except the 6’4’’ de Gaulle. The celebration continued until reaching the steps of Notre-Dame, when more shots occurred and, once again, de Gaulle remained standing. Inside Notre-Dame, more shots were fired, and the mass was ended prematurely.

To this day, the identity of the persons who fired the shots has never been determined, though speculation has ranged from German snipers to communist supporters, a theory held by de Gaulle. In the end, de Gaulle’s courage in the face of gunfire earned him the respect and control of France from that day forward.

Aftermath

The liberation of Paris came at a cost to both sides. Almost 15,000 Germans became prisoners of war, while in the two-day battle with the 2e DB, between 2,800 to 3,200 Germans were killed, most from Aulock’s units in the Boineburg Line. It is calculated another 1,000 Germans were killed in the week-long fighting against the FFI. The final figures for Leclerc’s division ended with around 630 dead and wounded. Only a few tanks were damaged, on August 25.

For the citizens of Paris, who had started fighting with the takeover of the Prefecture on August 19, casualty figures were high. One source listed 901 FFI members dead, with an additional 1,455 wounded. Civilian casualties were put at 582 killed and 2,012 wounded.

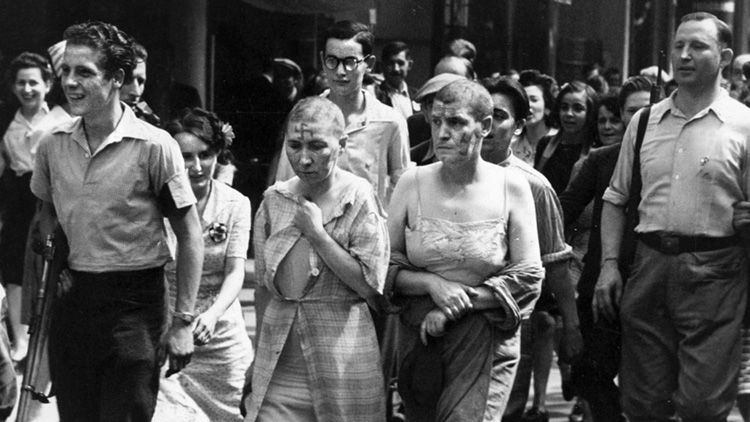

After the liberation, the more aggressive Parisians brutally rounded up collaborators. Those French women who had sexual relationships with their occupiers were publicly humiliated by having their heads shaved.

On August 27, General Eisenhower arrived in Paris to congratulate de Gaulle. During the meeting Eisenhower agreed to have two divisions march through Paris on their way to the front. Two days later the U.S. 28th Infantry and 5th Armored Divisions paraded down the Champs-Élysées for de Gaulle to review, then went into combat. This gesture cemented Franco-American relations. That same day, de Gaulle dissolved the upper command levels of the FFI in Paris.

The 2e DB remained in Paris for a couple more weeks before rejoining the war effort. Leclerc’s men would go on to surprise the Germans again in a lighting drive through enemy lines to capture Strasbourg. As a result of his determination, courage, and leadership skills, De Gaulle firmly entrenched himself as leader of France for years to come.

A miraculous sequence of events—and having the right people in right places—led to the liberation of the French capital without its destruction. Generals Eisenhower and Bradley understood the importance of Paris to the Allies in political terms as well as its positive psychological effect on the French.

Others played major roles, as well: General von Choltitz, who risked not only his life but that of his family when he disobeyed Hitler’s order to destroy the city; the leaders of the Resistance in Paris, who forced Eisenhower’s hand to have the city liberated instead of bypassed; General Charles de Gaulle, who had the strength to keep the French Republic alive after its defeat and unite its population; and General Philippe Leclerc, who often disobeyed orders from his superiors to insure the liberation of Paris in August 1944.