By Chuck Lewis

Deral Mosby is hooked. In a little over two years, the 58-year-old retired chemist’s collection of 20th-century military-surplus firearms has evolved from a handful of Russian Mosin Nagant infantry rifles valued at around $125 each to an ever-growing horde of Finnish military rifles and carbines, some of which are quite rare and worth considerably more.

Mosby isn’t alone. The collecting of Finn militaria—especially the Mosin Nagant variations of Finnish bolt-action military rifle—has exploded over the past decade. Like many Finn collectors, Mosby started with inexpensive Russian military firearms, which flooded the market after the fall of the Soviet Union’s eastern bloc. “I purchased several Russian Mosin Nagants and pretty quickly realized that the Russians had produced too many of the more common Mosins to make them collectible,” Mosby says. “Although there are several collectible variations of Russian Mosin Nagants, I was on my way to focusing on the Finnish Mosins. Reading everything I could get my hands on led me pretty early to realize that the Finnish Mosin Nagants would be more collectible since their production numbers were far less than that of the Russians. I also became very interested in the history of these Mosins. I found a collectible category of rifles with an intriguing history.”

An intriguing history, indeed. Most collectors of Finn militaria have a deep interest in military history and the struggles of Finland are tied inextricably to some of the most titanic events in 20th-century European geopolitics. One consequence of the Russian Revolution of 1917 was the founding of Finland as a nation independent of Russia. Soon after Finnish independence was declared in December 1917, Finnish factions became embroiled in a civil war similar to that between Russian “Reds” and “Whites” after the Bolshevik Revolution. By May 1918, troops of the new “White” Finnish government, with the help of a division of German soldiers, had overcome the “Red” Finnish forces, which had allied with garrisons of Russian troops stationed in Finland.

The reputation of Finnish people as tough and tenacious fighters was forged during the Winter War of 1939 and 1940. Massive numbers of troops from the Soviet Union attacked Finland on November 30, 1939, and Joseph Stalin’s forces clearly expected an easy victory. By March 1940, the Soviet Union had its victory, but it wasn’t easy. The vastly outnumbered Finns suffered an estimated 70,000 in dead and wounded, but the Russians suffered around 600,000 casualties in the short but deadly war. The 1940 peace treaty forced Finland to relinquish to Russia around 10 percent of its land and 20 percent of its industry. More than 400,000 Finns lost their homes. The Winter War hurt Finland, but it remained a sovereign nation despite overwhelming odds. The Soviet Union earned the ire of much of the world because of its unprovoked attack and was expelled from the League of Nations.

Finland declared itself neutral when Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, but the country did allow German troops and aircraft on its soil. After Russia bombed Finnish towns on June 25, Finland declared war on the Soviet Union. The goal of the Finnish government was to regain the land lost to Russia in the Winter War, which it accomplished. Finland was not a formal ally of Germany, and the nation did not declare war on the United States.

The Continuation War, as this conflict came to be known, lasted until September 1944 and resembled the Winter War in that outnumbered Finnish forces generally mauled Soviet units until the sheer weight of the Russian military machine prevailed. Eventually, Russia forced the Finns in late 1944 to sign a treaty that restored the borders set in 1940. Once again, the Russian bear had not been able to overrun Finland. Stalin reasoned that another such attempt would be extremely costly and did not pursue it. The end of the Continuation War meant another wary peace with Russia, but Finnish troops continued to see combat because, under the terms of the 1944 treaty, the Finns were required to fight any German units that remained on Finnish soil, which they did in several actions until nearly the end of World War II.

Combat is not the only connection between Russia and Finland. For decades, both nations equipped their armies with versions of the Mosin Nagant rifle and its 7.62-caliber cartridge. This curiosity is no coincidence. In fact, the use of the Mosin Nagant, a rifle first produced for the Czar’s troops in the 1890s, is tied to the origins of the Finnish nation near the end of World War I. Because Finnish “White” forces captured enormous numbers of Russian Mosin Nagant infantry rifles and ammunition during the 1918 Finnish Civil War, the new Finnish government adopted the firearm and its ammunition.

During the 1920s, Finland accumulated more Russian Mosin Nagant rifles through purchase or trade with several other nations that had captured stores of the weapon from the Russians during World War I. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the resourceful and thrifty Finns upgraded the Russian Mosin Nagants and also produced several of their own designs of Mosin Nagant-based rifles and carbines. However, while the Finns manufactured barrels and most other firearm parts, they always used salvaged Russian rifle receivers in the construction of their own Mosin Nagants. And because Finnish troops had captured hundreds of thousands more Mosin Nagants during the Winter and Continuation wars, Finnish armorers never suffered an extreme shortage of original receivers.

The Mosin Nagant connection between Finland and Russia has been a key element in the rapid growth of Finn militaria collecting in recent years. Mosby’s transition from collecting inexpensive Russian Mosin Nagants to the relatively rarer Finnish models has been repeated by throngs of collectors since the mid-1990s. Another factor fueling the collecting expansion is that Finnish versions of Mosin Nagants, while more expensive than the more common Russian models, have for the most part been reasonably priced. At a gun show, one might come across an excellent-condition Model 27 Finn Mosin Nagant, which is among the more highly prized Finn firearms, for a price of $200 to $350. A matching German K98 or average-condition American-made M1 Garand could easily bring double that amount.

Mosin Nagant collectors are also motivated by the relative scarcity of the rifles. The Soviet Union produced around 12 million of its standard infantry rifle, the Model 91/30, from 1930 through 1944. The Finns produced fewer than 70,000 of its standard army rifle, the Model 27, from 1927 to 1940. Perhaps in part because of the lower production numbers, the quality of Finn weapons is considerably higher than that of their Russian counterparts.

Besides an interesting history, relative scarcity, reasonable prices, and quality craftsmanship, what else could be fueling the growth of Finn collecting? The answer is variety. The variations of Finn militaria—especially Mosin Nagant firearms—are seemingly endless. One factor influencing the wealth of variations is the structure of the Finnish armed forces from the 1920s through World War II. Numerous well-organized Civil Guard units—similar, in some ways, to colonial America’s militia bolstered Finland’s regular army. Finland’s Civil Guard, the Suojeluskunta, adopted its own designs of Mosin Nagant firearms, such as the Model 28 rifle.

Civil Guard property, from rifles to field gear, was marked with an “SY” in the early years and with an “SK.Y.” in later years. Both are symbols of the Civil Guard high command, the Suojeluskuntian Ylieskunta. Civil Guard units also often stamped firearms with numbers assigned to their specific district, meaning that collectors can determine a rifle’s Civil Guard home and know at least part of the rifle’s history. Regular troops also carried gear with specific markings. The Finnish Army, the Suomen Armeija, eventually marked its firearms and gear with an “SA” abbreviation. When one considers Finn Mosin Nagant firearms with varying Civil Guard or regular army stampings, and then adds dozens of additional marks for arsenals, production years, depots, inspectors, barrel dimensions, pressure proofs, etc., Finn collecting gets quite interesting.

When one adds Russian variables to Finn collecting, the hobby gets downright fascinating. Because the Finns always used Russian rifle receivers on their versions of Mosin Nagants, most collectors enjoy taking apart each Finnish Mosin Nagant acquisition to peek at the underside of the receiver’s tang. It is there that the original Russian arsenal mark and production year will be stamped, unless a Finn armorer removed it. Therefore, a collector may acquire a 1928 Model 27 Finn Rifle and, after disassembly, find a receiver-tang stamp indicating that the receiver was made at the Russian arsenal of Tula in 1895. This would be a pleasant surprise, since it means that the firearm is a legal antique under federal firearms regulations.

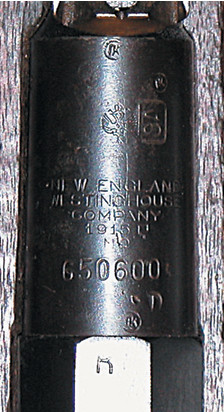

Another Russian variable is that the Finns often would simply refurbish or rebuild a captured Russian Mosin Nagant, stamp it with the “SA” Finnish Army property mark, and then reissue or store it. This means all of the elements that make the collection of Russian Mosin Nagants interesting become variables in Finn collecting. For example, two American companies, Remington and New England Westinghouse, produced some Russian Mosin Nagant Model 91 infantry rifles during World War I. If a collector came across a Remington Model 91 Mosin Nagant made in 1916 with Russian proof marks and an “SA” stamp, the collector would know that the rifle was produced in 1916 by an American company, taken into service by the Czar’s forces, and captured by the Finns in the 1918 civil war or by one of Russia’s enemies and sold or traded to Finland. How could such a journey not be fascinating to militaria collectors?

There was a time, two decades ago, when the collecting community frowned upon Finn-stamped Mosin Nagants and other Finnish militaria. Such military surplus commanded little attention, and as a consequence cost little. During that period some of today’s most seasoned and successful Finn militaria collectors—people such as Vic Thomas of Livonia, Mich:—began to take notice. “Back in the beginning I started with Japanese items as they were cheap and plentiful,” Thomas says. “At 18 you don’t have a lot of money to spend so you have to stretch your dollars. I had always been interested in the Nordic wars of World War II, being a northerner and living in a state that has a large Finnish community. As I learned more I started to search out Finnish items. Way back then, the Russian guns were often tossed aside if they had an ‘SA’ on them, as they were not ‘pure.’ So, the guns and militaria fit into my budget and were exciting to me. Prior to the Internet, the interest in Finnish collecting was very small. There were perhaps a handful of us in the United States who took it very seriously.”

Since then, Thomas, a 42-year-old owner of a dental laboratory, has amassed a collection of Finnish militaria that includes hundreds of weapons and thousands of other items, such as uniforms, field gear, and insignia. Thomas has also amassed a huge amount of information, something serious collectors crave just as much as the next great find at an auction or flea market. Through the years, Thomas has gathered information on Finnish militaria through such means as printed reference works, corresponding with other collectors, developing friendships with museum curators, and frequent trips to Finland. Now there’s the Internet where, as Thomas points out, “the world shrinks to the size of your screen.”

These days, Thomas helps disseminate more information through the Internet than he gathers from it because in addition to owning a dental lab, he co-owns Gunboards.com, one of the hottest Internet sites for military-surplus collectors. For Finn collectors, an important part of the Gunboards.com offerings is the Mosin-Nagant.net homepage. The “Finnish Area” of the homepage offers two dozen extremely detailed sections covering all major variations of Finnish Mosin Nagants, as well as other Finn weapons. Also detailed are Finn helmets, tunics, field gear, re-enacting activities, and various histories.

Thomas’s partner, Brent Snodgrass of Knoxville, Tenn., started Gunboards.com in 1995. Most Gunboards.com members know Snodgrass as Tuco, which is his forum member name. Snodgrass, whose 10-year interest in Finnish militaria has expanded into a full-fledged addiction, collects just about everything connected with the Finn military, including a 1943 120mm mortar that at more than six feet tall is quite an eye-catching item, according to the 36-year-old collector.

Snodgrass says he started Gunboards.com because he saw no Internet discussion boards for military-surplus collectors. “At that time the few firearms discussion boards on the Net focused on more modern arms, such as the AK, the AR15, the FAL and the like,” he notes. “I saw a need for a dedicated system for military-surplus collectors and so went forward with the site that over the years evolved into Gunboards.com. I can recall that not many people felt the idea would catch on, and I was called a nut for even attempting it. Now, 10 years later, I can claim that my idea was a success and also acted as a standard for most of the boards that are now on the net. For Gunboards to be the oldest such site on the Internet is a nice achievement, and I am very proud of this fact. We are now the largest such site in existence.”

According to Thomas, Gunboards.com now averages 1.4 million hits a month from users around the globe, and the site offers information from some of the best experts and collectors in the world. Of course, Gunboards.com is not the only game in town. Several other Internet sites also offer credible and substantive information for Finn militaria collectors. One site that has expanded rapidly over the past two years is 7.62x54r.net, founded by 39-year-old Ted Derryberry of Marietta, Geo. Derryberry, a forum moderator for Gunboards.com, makes extensive use of photos on his site and offers detailed, no-nonsense advice on such topics as buying and selling military surplus. Another site is Bob Wheeler’s Russian Mosin Nagant Page, which provides articles, editorials, and forums, concerning Mosin Nagants. His “Finn Section” provides superior images and facts. Finn collectors also frequent the Mosin Nagant Forum of Milsurpshooter.net to participate in discussions related to Finnish Mosin Nagants.

The most accessible printed reference works for U.S.-based collectors are Terence Lapin’s The Mosin-Nagant Rifle and Doug Bowser’s Rifles of the White Death. However, according to Thomas, the most authoritive work for the Finn collector is the three-volume set written by the director of the Finnish war museum, Marrku Palokangas. It’s titled Sotilaskasiaseet Suomessaa 1918-1988 and is out of print. The set costs $350 or more for those fortunate enough to find it.

What is the future of Finnish militaria collecting? For Snodgrass the increased popularity of Finn collecting is a mixed blessing. “The market is growing as there are more and more collectors entering the field,” he says. “This is causing the prices of Finnish items to rise, and it is also creating a market with more competition. The downside is that Finnish items have always been rare, so with more buyers out there, it is less likely that one will stumble into the great finds that the past offered. There are no vast amounts of Finnish items out there, so you have more people after a limited number of items. Still, even though this has grown as a hobby the overall numbers of Finnish collectors are low when compared to collectors of German, Russian, Japanese, or U.S. items. It will be interesting to see if many of these new collectors stay in the field or decide to move on—that is, once they discover how hard it is to build a large Finnish militaria collection.”

Thomas sees Finn collecting moving more into the mainstream as collectors search for alternatives to the saturated and high-end markets of German, Japanese, and American militaria collecting. “One has to remember that the market and available items are not very large to start with,” he says. “The nation has only 5.5 million inhabitants, and the amount of war materiel is finite as they used what they had in training and in reserve up until it was either too worn out to continue or the weapons too obsolete and expensive to store. So, the number of items in the pipe is not very large, and I don’t see an endless stream of new Finnish militaria collectors in the future as the market will only bear so many. I think that orders and decorations will continue to grow as will some items like headgear, but overall weapons will sooner or later have to tail off, as will uniforms because the remaining amounts of wartime items are dwindling each year.”

However, newer Finn collectors such as Deral Mosby will likely stick with it. He’s had “a rather intense two years” of collecting, he says, and has faced a “steep learning curve.” But, he adds, he’s “loved every minute of it.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments