By Sam McGowan

In 1995 the Department of Defense conducted a final investigation of the December 7, 1941, attack on U.S. military installations on Oahu, Hawaii. Four years later President William Jefferson Clinton signed a Congressional Resolution that reinstated the ranks of the two principal commanders, Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, the commander of the Hawaiian Department of the U.S. Army, and Admiral Husband C. Kimmel, the commander-in-chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at the time of the attack.

The congressional action apparently infuriated authors John W. Lambert and Norman Polmar. In Defenseless: Command Failure at Pearl Harbor (Motorbooks International, St. Paul, Minn., 2004, 225 pp., photographs, $27.95, hardcover), they attempt to set the record straight and “prove” that Kimmel and Short were guilty of dereliction of duty. Their allegations come up short when considering all of the evidence at hand, including information contained within their own book.

The congressional action apparently infuriated authors John W. Lambert and Norman Polmar. In Defenseless: Command Failure at Pearl Harbor (Motorbooks International, St. Paul, Minn., 2004, 225 pp., photographs, $27.95, hardcover), they attempt to set the record straight and “prove” that Kimmel and Short were guilty of dereliction of duty. Their allegations come up short when considering all of the evidence at hand, including information contained within their own book.

A major focus is on the U.S. Army Aircraft Warning Service that was in the process of implementation on Oahu when the attacks took place. As is well known, one of the radar sets picked up a return that was later discovered to have been the Japanese attacking force while the enemy planes were still approximately 150 miles out to sea. There is a lot of confusion over the manner in which the authors present the information related to this system. In several instances they refer to it as “operational,” while in others they point out that although some of the sets were in operation, the aircraft early warning system itself had yet to be declared serviceable.

There is also a lot of discussion that the “information center,” which was supposed to be the collector of information received from the radar sites, was not properly manned, with emphasis on the absence of U.S. Navy and Army bomber squadron liaison personnel. They believe that if those two services had been represented, center personnel would have somehow known that the blips picked up by two radar operator trainees were not U.S. military aircraft, as the officer on watch reckoned them to be. The failure of the system to have reached operational status is one of the charges they lay on General Short.

Another of their charges of dereliction of duty on the part of both Short and Kimmel is the failure to perform reconnaissance “as ordered” in a message that was dispatched to all of the key military commanders in the Pacific on November 27, 1941, a full 10 days before the attack. However, the authors fail to discuss the true nature of this order, which was sent out jointly by the War Department and Department of the Navy, apparently in response to a White House directive.

The message warned that negotiations with the Japanese were on the verge of breakdown and that the possibility of war was imminent. Lambert and Polmar imply that the message was aimed solely at Hawaii when, in fact, the primary impetus was toward areas that were in close proximity to Japanese territory, specifically the Philippines and the Pacific islands such as Midway and Wake.

Furthermore, the main focus of the message was that “the United States,” meaning the administration of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, wanted the Japanese to “commit the first overt act,” an almost unbelievable command to which the authors do not devote a single word. This command effectively tied the hands of the military commanders, essentially instructing them that they were not to fire until fired upon.

Nor do the authors recognize that the message was not aimed solely at Short and Kimmel, but that they were only two on a list of recipients. The message did inform commanders that they should “undertake such reconnaissance and other measures as you deem necessary.” In short, it left the appropriate actions up to the discretion of the commanders. The message also stated that in the event of hostile action by the Japanese, the commanders were to carry out the tasks assigned by the Rainbow Number 5 war plan, which was to reinforce the Philippines.

The authors take Kimmel and Short to task for not implementing aerial reconnaissance, but fail to recognize that they truly lacked the capabilities of conducting a complete and thorough survey on a daily basis. Although the Hawaii-based air force was equipped on paper with some 234 aircraft, barely half of them were operational on the morning of December 7, and of those that were, less than a dozen would have been capable of reaching the Japanese fleet in time to have issued a warning. Even if they had been sent out on searches, there is no guarantee they would have searched in the right direction, since the Japanese carrier fleet was to the north rather than in the direction of the nearest Japanese territory where searches would most likely have been conducted.

The authors make much of the presence of 33 Douglas B-18 bombers in the islands and lament the fact that they were not considered suitable for long-range reconnaissance. The information shown in the book’s appendix, however, shows that only two of the already obsolete B-18s were in commission. They also exaggerate the B-18’s capabilities, stating that it had a search radius of 500 miles, when in reality it was capable of barely half that much. The error is based on an interpretation of the actual airspeed of the already obsolete twin-engine bombers using the published “top speed” of 217 mph, which is actually the maximum allowable speed—a structural determination—and which is rarely achieved by any airplane except during descent.

This is a mistake commonly made by aviation writers such as Lambert, who has authored and published several books on World War II aircraft. A B-18 might have been able to search out to just under 300 miles and make it back with an adequate supply of fuel.

The other operational airplanes that might have been suitable were five Boeing B-17s and an equal number of Douglas A-20 light bombers. Actually, the B-17s were the only Army airplanes then in Hawaii that had the capability of searching far enough out to have detected the Japanese fleet in time to have sent a warning; the A-20s were short-range light bombers. The Navy had about 50 operational Consolidated PBY patrol planes, but most of them were dedicated to antisubmarine warfare and support of the Pacific Fleet; the Navy was reluctant to release them for long-range searches.

The Navy’s aircraft carriers—the main targets of the Japanese—and their planes were at sea on orders from Washington, transporting aircraft to reinforce Wake Island and Midway, and were well west of the approaching Japanese fleet.

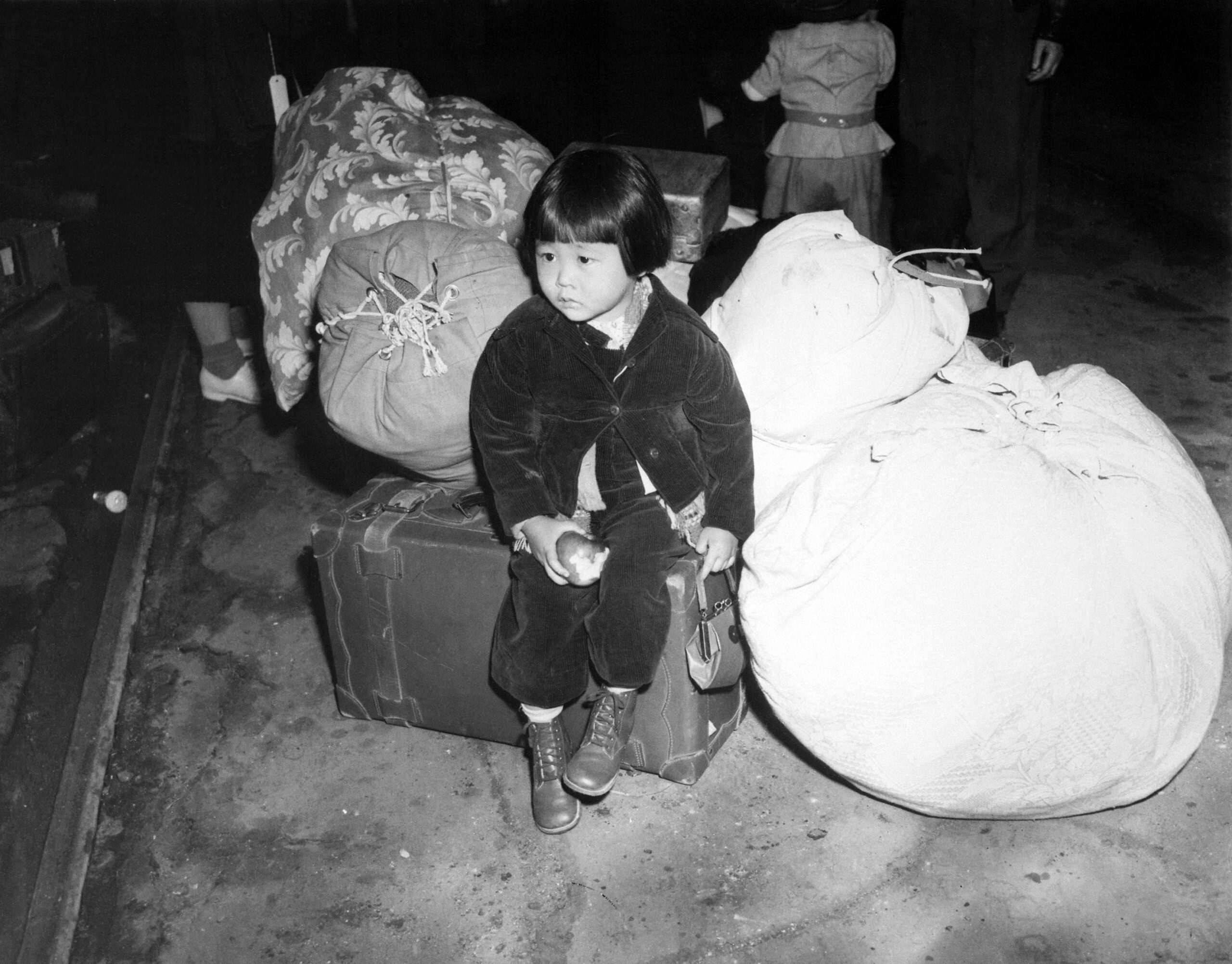

The authors also fault Short for failing to maintain an alert force of fighters. In fact, the 14th Pursuit Group air and ground crews had been on alert for several days prior to the attack, but upon receipt of the November 27 message, General Short changed the alert status from defense against air attack to defending the airplanes against possible sabotage. After all, large numbers of Japanese immigrants were found among the population of Oahu, and even though the gift of 20/20 hindsight reveals that they were not a danger, in 1941 there was little reason to believe they would not be loyal to their native land.

There was also the possibility of Japanese sabotage teams being put ashore from submarines, an issue that Lambert and Polmar decline to address. Short, as did every other officer in the chain of command all the way up to and including President Roosevelt, believed that the Japanese attacks would come in the Philippines and did not feel that an air attack on Oahu was likely. Similarly, Kimmel believed that the most likely threat against Pearl Harbor would come from submarines and that defense against them was the proper mission for his PBYs.

Lambert and Polmar lament that Short changed from the “historic” threat of air attack to defense against sabotage, but their use of the modifier is not solidly based on fact. Granted, some U.S. planners had considered the possibility of an air attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese carrier-borne aircraft, but prior to December 7, few American military officers and government officials believed that Japan was capable of such a long-range strike.

The authors condemn Admiral Kimmel for not recognizing that the U.S. intelligence failure to determine the location of two Japanese carrier groups meant that Pearl Harbor was in danger. However, they have something that Kimmel did not have: the ability to look back on what actually took place rather than to ponder the mind of a potential enemy who was expected to strike—and did—thousands of miles away in Southeast Asia.

After all, if the Navy Department, which had better intelligence than Kimmel, believed that the Pacific Fleet was in danger, why did it not order the entire fleet to depart Pearl Harbor for the open sea, where it would have been able to maneuver, or to intercept an approaching Japanese task force? For that matter, no one ever seems to ask the question of why the fleet was not dispatched to where it would be in a better position to come to the aid of the Philippines, which were believed to be in danger.

In spite of its failure to prove the authors’ point, this book is a good source of information about the events just prior to the attacks and the military situation at the time.

Pappy Gunn, by Nathaniel Gunn, 1st Books Library, Bloomington, Ind., 2004, 350 pp., photographs, $25.00, hardcover.

Pappy Gunn, by Nathaniel Gunn, 1st Books Library, Bloomington, Ind., 2004, 350 pp., photographs, $25.00, hardcover.

If there is a single individual who personifies World War II in the Pacific, it is Lt. Col. Paul Irving “Pappy” Gunn, the crusty Arkansan and former U.S. Naval aviator that Far East Air Forces commander Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney often referred to as “my secret weapon.”

In the war from day one, when he was put in charge of transport operations in the Philippines, Gunn still would have been in it the day the Japanese surrendered had it not been for the tiny piece of white phosphorous that put him in the hospital during the invasion of Leyte. However, during the almost three years between the Japanese attack on Clark Field and his near-paralyzing wound, Pappy Gunn racked up a record that has no parallel. He literally became a legend, both in the U.S. Army Air Forces in which he served and the U.S. Navy that was his home for most of the years between the wars.

Written by Pappy’s youngest son Nathaniel, Pappy Gunn tells the full story of the man who is best known for modifying the North American B-25 Mitchell and transforming it from a run-of-the-mill medium bomber into the powerful gunship that played a major role in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. While the conversion of the B-25s and the A-20s that preceded them was one of Gunn’s greatest accomplishments, it was but one of many: the rescue of stranded pilots, the recovery of abandoned B-17s, and the organization of an air transportation command in Australia.

The aviator/innovator was a driven man; he was fighting his own personal war against the Japanese who were holding his entire family, including the author, in an internment camp in Manila. All Gunn knew about his family was that they were being held in the Santo Tomas camp, and all the family knew was that he had flown out of the Philippines on a special mission at the end of 1941 and had not come back.

To tell his father’s story, Nathaniel Gunn interviewed family members as well as several men who had been with his father before and during the war, then set out to obtain as much documentation as he could in an attempt to separate the man from the legend. The book is filled with reproductions of orders, mission reports, and personal accounts by some of the men who knew and flew with his father from 1942 to 1944.

Nathaniel has also included several never-before-published photographs of his dad and his family, including a family photograph that was taken in the hospital at Brisbane where the family was reunited. He tells his tale from the perspective of a son who was privileged to meet some of the men who held his father in high regard. He also heard some of the stories they told firsthand during the years when he lived and worked with his father in the Philippines after the war.

The author pulls no punches. He has included material and information that other members of his family did not really want to have publicized, but which help to reveal the persona of the real Pappy Gunn. He also reveals that his father was ordered out of the Philippines without being told that he would not be returning.

Consequently, the family was left to its own devices, a situation that embittered Gunn against some of the higher ranking officers in the Far East Air Forces. Gunn and his family, along with other Americans who were trapped in the Philippines by the war, were bitter at President Roosevelt’s refusal to order an evacuation of civilians from the islands even though he knew a Japanese attack was imminent. Roosevelt did not want the Filipino people to think he was abandoning them.

Pappy Gunn is an important book because it not only tells the subject’s story, but the author is able to include an account of his family’s experiences in an interment camp from the unique perspective of having been there. Being well aware of how the Japanese treated their Chinese victims at Nanking, Colonel Gunn was terrified that his 40-year-old wife and teenage daughters were being subjected to the ravages of lusty Japanese soldiers. This fear made him a driven man; his appearance and some of his actions indicated that he was an individual with a severe emotional disturbance.

Those who crossed Pappy Gunn suddenly found themselves looking down the barrels of his twin .45s. Small wonder—the man’s entire family was in enemy hands and the United States government seemed to be dragging its feet in its efforts to rescue them!

This is a book that anyone with even a passing interest in World War II should read. Millions of men and women served during the war, but there was only one Pappy Gunn, and this is his story as told by his son.

Duty, Honor, Victory: America’s Athletes in World War II, by Gary L. Bloomfield, The Lyons Press, Guilford, Conn., 2003, 392 pp., $20.95, hardcover.

Duty, Honor, Victory: America’s Athletes in World War II, by Gary L. Bloomfield, The Lyons Press, Guilford, Conn., 2003, 392 pp., $20.95, hardcover.

The title, a takeoff on the U.S. Military Academy motto “Duty, Honor, Country,” implies that the book is about the wartime service of professional athletes. While it is that, it is actually about athletes of all categories, ranging from young collegiate players and those who had gained some kind of recognition on the high school athletic field to those who were experts in many kinds of athletic endeavors.

Former members of the Annapolis and West Point athletic teams are frequently mentioned, which is to be expected since the role of both schools was to train military leaders. Many of the best-known military personalities of the period had excelled in athletics in their youth. Douglas MacArthur was a member of both the baseball and football teams at West Point, and George Patton was an Olympic competitor, just to name two.

The author, a former editor of VFW Magazine, has compiled information concerning hundreds of men and a few women whose lives involved athletics before, during, and after the war years and arranged them into vignettes and anecdotes relating the role of athletes in the war.

The narrative is arranged in sections, each relating either to a specific category, service, or theater of war, with the names of individuals who are connected to that topic. Not all of those mentioned are known as athletes; singing cowboy actor Gene Autry’s service as a pilot with the Air Transport Command is mentioned because of his later ownership of the California Angels baseball franchise.

The only major criticism of the work is that coverage of most subjects is very brief, often confined to a single sentence. Bloomfield only devotes one sentence to University of North Carolina tennis star Ramsay Potts. He relates how Potts was awarded an Air Medal for service in North Africa in 1942, but Major Potts was the deputy lead pilot for the 93rd Bombardment Group on the famous low-level raid on the Ploesti oil fields on August 1, 1943. Ironically, this very mission is covered in a subsection and Potts isn’t mentioned. Apparently the author was not aware of the relationship.

There are some surprises. For example, baseball legend Jackie Robinson was commissioned as an officer but was pulled out of his unit before it went overseas after he got into an altercation with a bus driver and was ultimately discharged from the Army. While many of the better-known athletes of the day, as well as some of those who were less well known, wore the uniform, their service was often as fitness instructors and some spent their time in service playing on unit teams, often at the insistence of their commanding officers.

Although Ted Williams was a pilot in the Marine Corps, his athletic reputation kept him in the United States until the very end of the war. By the time he got to the Pacific the Japanese had surrendered. Williams did serve in combat during the Korean War. Several prominent athletes were discharged as early as 1944 to return to their teams.

This is not a book one would necessarily want to sit down and read cover to cover, but it does contain a lot of interesting information. It would make an ideal gift for the sports enthusiast.

The Bomber War, by Robin Neilland, The Overlook Press, Woodstock NY, 2004, 448 pp., $17.95.

This has the makings of a great book. Unfortunately, Robin Neilland, a highly respected military historical author, failed to do adequate research and the result is a book filled with factual errors that detract from his stated purpose: to examine the role of bombing in the war in Europe to determine if the RAF Bomber Command was truly guilty of “terror bombing.”

To those not familiar with the history of the air war over Europe, The Bomber War would appear to be a definitive history of aerial bombing, but it is not. Granted, Neilland’s accounts of the inner workings of the RAF and the RAF Bomber Command are very informative. It is in the area of day-to-day operations and the organization of the U.S. Army Air Forces (he constantly refers to the U.S. Army Air Force) that the work starts to fall short. He equates the Eighth Air Force to the entire Royal Air Force, when in fact the Eighth was but one of 11 numbered theater air forces. Although the Eighth and Fifteenth were somewhat unique in that they were organized after 1943 for the sole mission of strategic bombing.

Neilland is also shaky on the history of the Eighth, claiming that it evolved from the Army Air Combat Command since General Carl Spaatz commanded that organization prior to taking command of the Eighth. In fact, the Eighth was originally formed to support the invasion of North Africa. He misdates the organization of the Fifteenth Air Force, which along with the Eighth made up the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in Europe, placing it in operation in the fall of 1942 when in fact it was not organized until a year later.

Another of the book’s serious errors is the constant implication that the arrival of the Republic P-51 Mustang fighter in the European Theater enabled the Allies to gain air superiority. In fact, while they were very capable fighters, P-51s with the range to go deep into Germany were not available in large numbers until mid-1944, by which time the Luftwaffe was already losing control of the skies to drop-tank- equipped P-38s and P-47s as well as the few P-51s that were available.

Neilland seems to have a tendency toward repetition. One example is the constant assertion that the arrival of the P-51s allowed “true” precision bombing by Eighth and Fifteenth Air Force bombers. In fact, even as German fighter opposition decreased, antiaircraft fire became more prevalent and more accurate. He repeats accounts of the development of electronic means of navigation and radar bombing several times and relates at least three times that when male German fighter controllers were replaced by women to counter British operatives, the RAF foresaw the move and began using their own German-speaking women to send false messages to Luftwaffe night fighters.

The author’s main point seems to be that while RAF Bomber Command practiced area bombing, U.S. Army bomber crews did essentially the same thing. He fails to grasp that “blind” radar bombing using H2X was still a form of precision bombing. Instead of acquiring the target visually, radar bombardiers determined their release points through radar mapping. In fact, after the war, radar bombing was the preferred method of dropping aerial weapons, including nuclear bombs, making visual bombsights obsolete.

The difference between RAF and U.S. radar bombing methods was that RAF bomb aimers in the Pathfinder Forces used their radar to find and mark city centers while, at least in most cases, U.S. bombardiers aimed for industrial areas. The results may have been the same—the death and injury of thousands of civilians—but at least the U.S. Army bombers were tasked to hit specific targets, not just the metropolitan areas that contained them.

American “lead” crews were assigned to lead each bomber group, with other bombers in the formation dropping when the lead bombardier released his bombs. RAF Pathfinders went in before the main force to light up the city centers with incendiaries and flares so the following bomb aimers would have something to direct them. Neilland does recognize that RAF Bomber Command was capable of highly accurate bombing, as evidenced by the dropping of huge “Tall Boy” 10,000-pound bombs later in the war, but their tactics centered around area bombing.

There are some serious exaggerations in the narrative. In his account of the air attacks on the Ploesti oil fields in the spring and summer of 1944, the author claims that each raid consisted of “more than 1,000” aircraft. In fact, the largest number of bombers that ever appeared over Ploesti was just over 600, while several missions were flown with less than 150 aircraft.

Neilland includes accounts from bomber veterans throughout the narrative to make his points. Some accounts do not have the ring of truth and do not square with Eighth Air Force operating procedures. One veteran refers to a “49th Bomb Group,” claiming this group was jumped by fighters on a particular mission and lost 14 out of 24 B-24 Liberator bombers, but there was no 49th Bombardment Group. The 49th was a fighter group with the Fifth Air Force in the Southwest Pacific.

The only B-24 group in the Eighth Air Force with a number close to 49 was the 44th Bombardment Group, and this may have been the group the veteran was thinking of, but Neilland failed to recognize the error. Why did the author not verify the information before including the comments in his book?

In spite of the inaccuracies, this is a worthwhile book for the reader who is interested in the political intrigue that was so prevalent within the Allied forces in Europe, particularly between RAF Bomber Command chief Arthur Harris and his superiors. Chapters are devoted to the development of various “scientific” methods to aid both the Allied bombers and the German defenders.

The reader, however, should be mindful that everything the author states does not exactly square with history. This is not a book one should readily accept as a historical account of the bomber war, at least not as it was fought by the U.S. Army Air Forces over Europe. Further, if the USAAF account is sometimes in error, who is to say that the author’s perception of RAF Bomber Command is not similarly flawed?

Devilish Snooks, by Neil F. Coleman, 1st Books Library, Bloomington, Ind., 2004, 222 pp., $17.50.

Devilish Snooks, by Neil F. Coleman, 1st Books Library, Bloomington, Ind., 2004, 222 pp., $17.50.

In March 1944, the first Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber crews departed the United States for India, where the commander of the U.S. Army Air Forces, General Henry H. Arnold, had decided to base them. Author Coleman was the central fire controller gunner of the very first crew to depart. His crew was one of a number of second crews from the 40th Bombardment Group who were sent overseas aboard Air Transport Command transports before the bombers departed. The crew arrived at its new base at Chakulia, India, as it was being beefed up to handle the huge Superfortresses.

As a second crew, and perhaps because the aircraft commander was at odds with the squadron commander from their previous assignment in the Caribbean, Coleman’s crew was rarely chosen for the combat missions. The airplane to which they were assigned as second crew was converted into a tanker and they alternated with the other crew on tanker missions hauling fuel to their advance base at Hsingching, China. After the crew had flown a few missions, it was temporarily pulled off B-29 operations, and the officers—including the commissioned flight engineer who had the rank of flight officer—were assigned to fly converted Liberator tankers (C-109s, commonly referred to as “C-One-Oh-Booms” because of their tendency to explode) on fuel-hauling missions over the Hump. After more than a year overseas, Coleman’s crew was still far from completing the required missions for a combat tour.

Finally, as other crews began rotating home and new B-29s came in as replacements, the crew was given its own airplane, which the men named “Devilish Snooks” after a cartoon character of the day. Not long afterward, all of the B-29s were pulled out of China and sent to the Marianas. Coleman’s crew ended up at West Field on the tiny island of Tinian. There it joined with other XXI Bomber Command crews in the now-massive B-29 raids that were designed to force the Japanese to their knees.

Devilish Snooks is an interesting and entertaining book. The author, a published novelist, writes in the third person and many, if not all, of the names have been changed to ensure privacy, a common practice with wartime memoirs. Much of the narrative is devoted to the day-to-day lives of members of the crew as they dealt with the deprivations of life at forward bases in backward countries.

The author’s accounts of the combat missions are short and to the point. They include recollections of highlights of missions of up to 16 hours in length. Most of these were boring over-water flights until the crew reached the semipermanent stationary front that seemed to serve as an advance picket for the Japanese early-warning system. Each night the crews had to penetrate the lightning- and turbulence- filled front on their way to and from the target. Turbulence over the burning cities was even worse, as the heated air rose so rapidly that it was nearly capable of ripping the wings off a B-29.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments