By Christopher Miskimon

The squat, gray brick Castle Aghinolfi sat on high ground over-looking a coastal road on Italy’s west coast. On April 5, 1945, German soldiers occupied the old Italian fortress. They sat squarely in the path of the advancing United States Army. In the hour before dawn, Lieutenant Vernon Baker led his men, the Weapons Platoon of C Company, 370th Infantry, up the slope before the castle. He had 25 men under his command, and they went up so smoothly they soon got ahead of the rest of the company. The platoon stopped at a spot about 250 yards from the structure so Baker could find a good spot to set up a .50-caliber machine gun. Friendly artillery fell nearby, masking the sound of the GIs’ movement.

Spotting some movement in the brush, Baker made out the silhouette of a German helmet. Taking aim in the early dawn light, he shot down two enemy soldiers. His men soon eliminated a machine-gun nest and emplaced their own weapon near it. The artillery also served to mask the sound of the Americans’ rifles, allowing them to surprise the enemy. As Baker looked around, the observant young lieutenant spotted a pair of cylindrical objects poking out of a slit on the side of a hill. He realized they were a pair of binoculars sticking out of an enemy observation post. The young officer moved up to the slit, stuck the barrel of his M-1 rifle through it, and emptied the eight-round clip into the two occupants, killing them both.

Advancing, the platoon stumbled on another machine-gun nest, its two-man crew enjoying breakfast, unaware of the nearby Americans. As soon as they saw the Americans, they scrambled for their gun, but Baker shot them both. Nearing the castle, the terrain became more difficult; only a narrow path through a draw allowed access, but it had to be well defended. Sure enough, a German appeared as Baker conferred with his company commander, Captain John Runyon. The German threw a grenade, which landed only five feet away. Runyon dove away while Baker shot the enemy soldier as he tried to run away. Luckily, the grenade proved to be a dud.

The next few minutes went by in a blur for the young officer. He went down the draw alone, blowing open the entry to a concealed fighting position with a hand grenade and shooting a German who came out. Baker threw a grenade inside, waited for the explosion, and went in, shooting two more Germans inside. When he came back out of the draw, German mortar and machine-gun fire tore into the platoon, killing or wounding about two-thirds of them within minutes. Runyon expected more men to arrive, but when they did not, he ordered a withdrawal in two groups. Baker stayed with the second to provide covering fire as the walking wounded fell back. He covered the second group, consisting of the more seriously wounded, by using hand grenades to destroy two more machine-gun nests they had not noticed earlier.

Baker’s actions were deserving of a Medal of Honor. Instead, because he was black, nine months later he received a Distinguished Service Cross. It took over 50 years to correct that failure. Luckily, Baker was still alive when, in 1997, he went to the White House and received his medal alongside the descendants of six other recipients whose awards came too late. The stories of all seven men are retold in Immortal Valor: The Black Medal of Honor Winners of World War II, Denied Recognition for 50 Years (Robert Child, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2022, 288 pages, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover).

Baker’s actions were deserving of a Medal of Honor. Instead, because he was black, nine months later he received a Distinguished Service Cross. It took over 50 years to correct that failure. Luckily, Baker was still alive when, in 1997, he went to the White House and received his medal alongside the descendants of six other recipients whose awards came too late. The stories of all seven men are retold in Immortal Valor: The Black Medal of Honor Winners of World War II, Denied Recognition for 50 Years (Robert Child, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2022, 288 pages, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover).

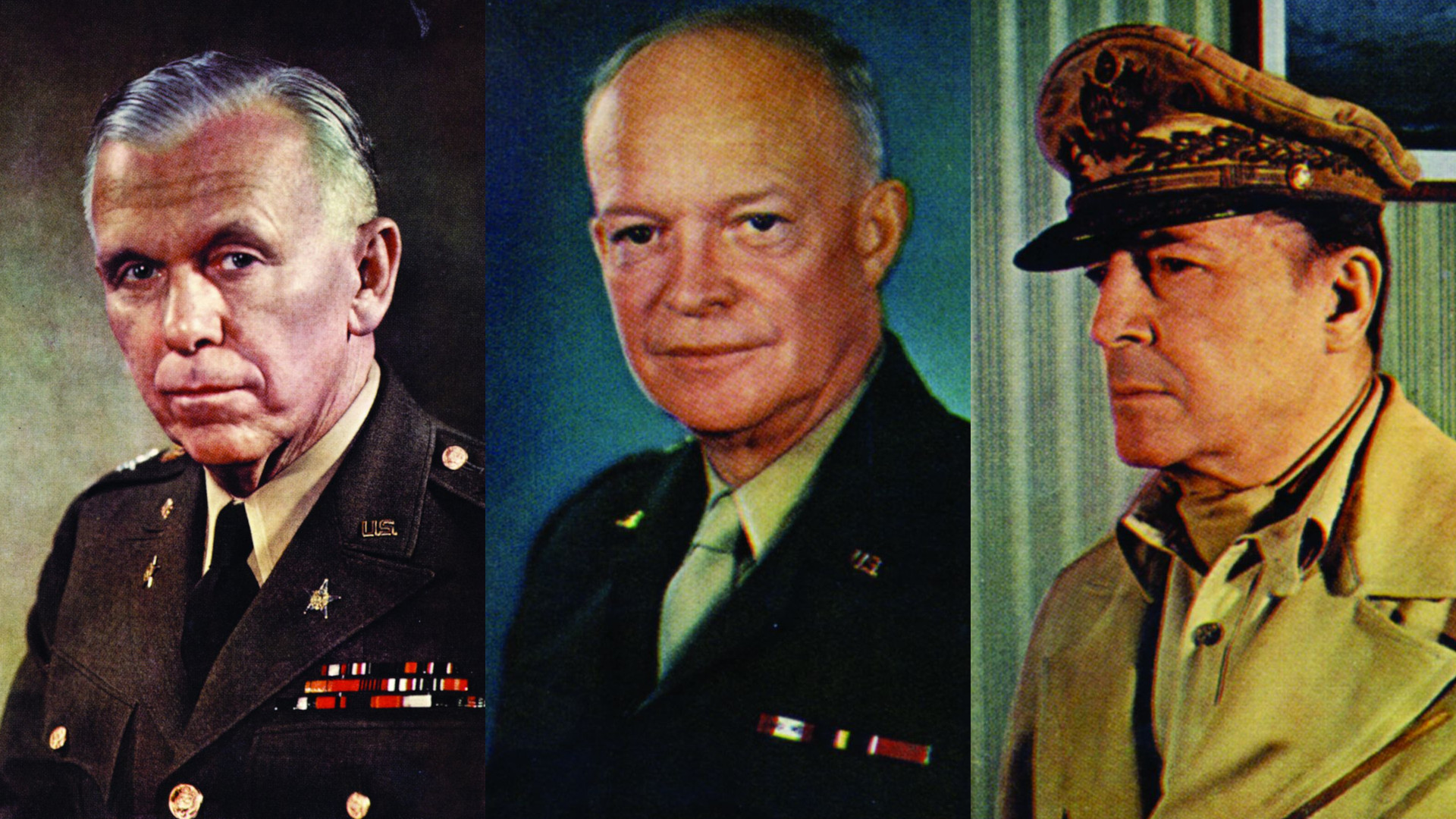

In 1993, the Army commissioned a panel to investigate instances where black soldiers may have deserved a Medal of Honor but did not receive the award. They reported back with seven names: Vernon Baker, Charles L. Thomas, Willy James Jr., Edward Allen Carter Jr., George Watson, Ruben Rivers, and John Fox. This book tells the story of each man, including how he entered the service, where he trained, his deployment into the combat theater, and the act that earned him his delayed award. The author deftly relays each man’s tale with a clear, detailed narrative and background information on the battle in which they performed their act of valor. The book is a fitting tribute to its subjects and brings to light information that should have been published long ago.

German Tanks in Normandy 1944: The Panzer, Sturmgeschutz and Panzerjager Forces that Faced the D-Day Invasion (Steven J. Zaloga, Osprey Books, Oxford, UK, 2021, 48 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $19.00, softcover)

German Tanks in Normandy 1944: The Panzer, Sturmgeschutz and Panzerjager Forces that Faced the D-Day Invasion (Steven J. Zaloga, Osprey Books, Oxford, UK, 2021, 48 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $19.00, softcover)

When the Allies invaded Normandy, the Germans had a substantial number of armored vehicles available to oppose them. However, few of the vaunted Tiger and Panther models were available, meaning most of the fighting occurred using a mix of older tanks, assault guns, and tank destroyers, some of which were obsolete. Most German units suffered from personnel and equipment shortages, and Allied air power harried them at every opportunity. Despite these limitations, they exacted a fearful toll on U.S. and British forces using the advantage of fighting on the defense and their extensive experience of war. Nevertheless, in the end, the Germans lost, beginning the long retreat to Germany and eventual defeat.

The author is an acknowledged expert on World War II armored combat, piercing the myths and falsehoods to reveal tank warfare as it occurred. This work carries his expertise forward in a concise, well-illustrated edition. The Germans and their capabilities are often overly mythologized, but this book is refreshingly honest about them, both good and bad. For example, the author explains how tank ace Michael Wittman’s skill led him to great victories, but his overconfidence subsequently brought about his demise. There are several original drawings and artwork, which is normal for this publisher’s work.

Battleship Commander: The Life of Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee Jr. (Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2021, 376 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $37.95, hardcover)

Battleship Commander: The Life of Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee Jr. (Paul Stillwell, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2021, 376 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $37.95, hardcover)

Willis Augustus Lee served in the United States Navy for nearly four decades. Medal of Honor winner George Street, who served under Lee on a cruiser before the war, said Lee was “bright as new money.” Lee’s skills both at operations and administration earned him great praise during the war. He had command of Battleship Division Six aboard the USS Washington during the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal. Lee’s leadership led to an American victory and the Japanese loss of the battleship Kirishima. This victory proved instrumental in turning the tide against Japan in the Solomon Islands. He was said to know more about radar than the radar’s operators. Later the Navy appointed him Commander, Battleships, Pacific Fleet, giving him authority over the fleet’s fast battleships. Near war’s end he received new orders transferring him to the Atlantic to oversee research on how to combat the kamikaze threat. The war ended a few months later, however, and Lee died of a heart attack 10 days after Japan surrendered.

Admiral Lee deserves to be more widely known than he is today, and this book is a fitting tribute to his naval career. The author takes us from Lee’s humble beginnings in Natlee, Kentucky, to his tragic death aboard a navy small boat transporting him to his office on Great Diamond Island near Portland, Maine. Between these two events lies the tale of a professional sailor who did his job well and deserves recognition for his skilled service.

Prevail Until the Bitter End: Germans in the Waning Years of World War II (Alexandra Lohse, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2021, 196 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Prevail Until the Bitter End: Germans in the Waning Years of World War II (Alexandra Lohse, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY, 2021, 196 pp., photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover)

A German lieutenant named Metzenthien had a lot to say about his fellow Germans as he sat in his POW’s cell near Toulon, France. The invading Allies captured the young officer on August 15, 1944, and he reflected on what he had seen while fighting in Russia and France and his travels in between. He thought many of the Germans on occupation duty in France treated the country as “one vast restaurant.” He could not blame the French for hating their Nazi overlords. Poland seemed full of officials more intent on personal plunder than the welfare of the Reich. However, he had only good things to say about the Germans on the home front, enduring bombing raids and living in tents after their homes were destroyed. He thought the war would go on for many more years due to their stoic resilience. Metzenthien expressed gratitude to Hitler for making Germany great again, though he did not think it mattered whether Hitler was the actual man doing it or what kind of government he created. Germany’s rebirth was all that mattered.

This new book provides answers to why the German people lasted as long as they did in World War II and examines the challenges for a totalitarian state at war. Often attributed to a slavish devotion to Hitler, the author reveals how and why Germans endured bombing and battlefield setbacks. The book also delves into the stresses of a nation at war and where some of the stress lines appeared. The author does an excellent job pulling the numerous factors together into a coherent history.

Dirty Eddie’s War: Based on the World War II Diary of Harry “Dirty Eddie” March, Jr., Pacific Fighter Ace (Lee Cook, University of North Texas Press, Denton, TX, 2021, 352 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Dirty Eddie’s War: Based on the World War II Diary of Harry “Dirty Eddie” March, Jr., Pacific Fighter Ace (Lee Cook, University of North Texas Press, Denton, TX, 2021, 352 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Harry March, nicknamed “Dirty Eddie” by his fellow pilots, served in four fighter squadrons during the war. Initially he flew from aircraft carriers covering the landing at Guadalcanal in August 1942. Later, he went ashore on that embattled island to fly with the famous “Cactus Air Force” from Henderson Field. He returned to combat at Bougainville, including missions over the Japanese base at Rabaul. March flew with “Fighting Seventeen,” the famous Vought F4U Corsair squadron noted for its daring exploits in combat. He ignored standing orders against keeping a diary, addressing his entries to his wife Elsa.

March’s diary reveals the thrill and strain of aerial combat while presenting the reader with the pilot’s own thoughts about the greater war surrounding him. The text shows him angry, happy, stressed, and at times longing to get back home. The author deftly mixes March’s diary entries with narratives about the war, giving context about where the young pilot was and how he fit into the war effort. The result is a fascinating look at the Pacific War through the eyes of a participant. The book also contains good maps and several interesting photographs from March’s collection and official sources.

Marine Raiders: The True Story of the Legendary WWII Battalions (Carol Engle Avriett, Regnery Publishing, Washington, DC, 2021, 270 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.99, hardcover)

Marine Raiders: The True Story of the Legendary WWII Battalions (Carol Engle Avriett, Regnery Publishing, Washington, DC, 2021, 270 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.99, hardcover)

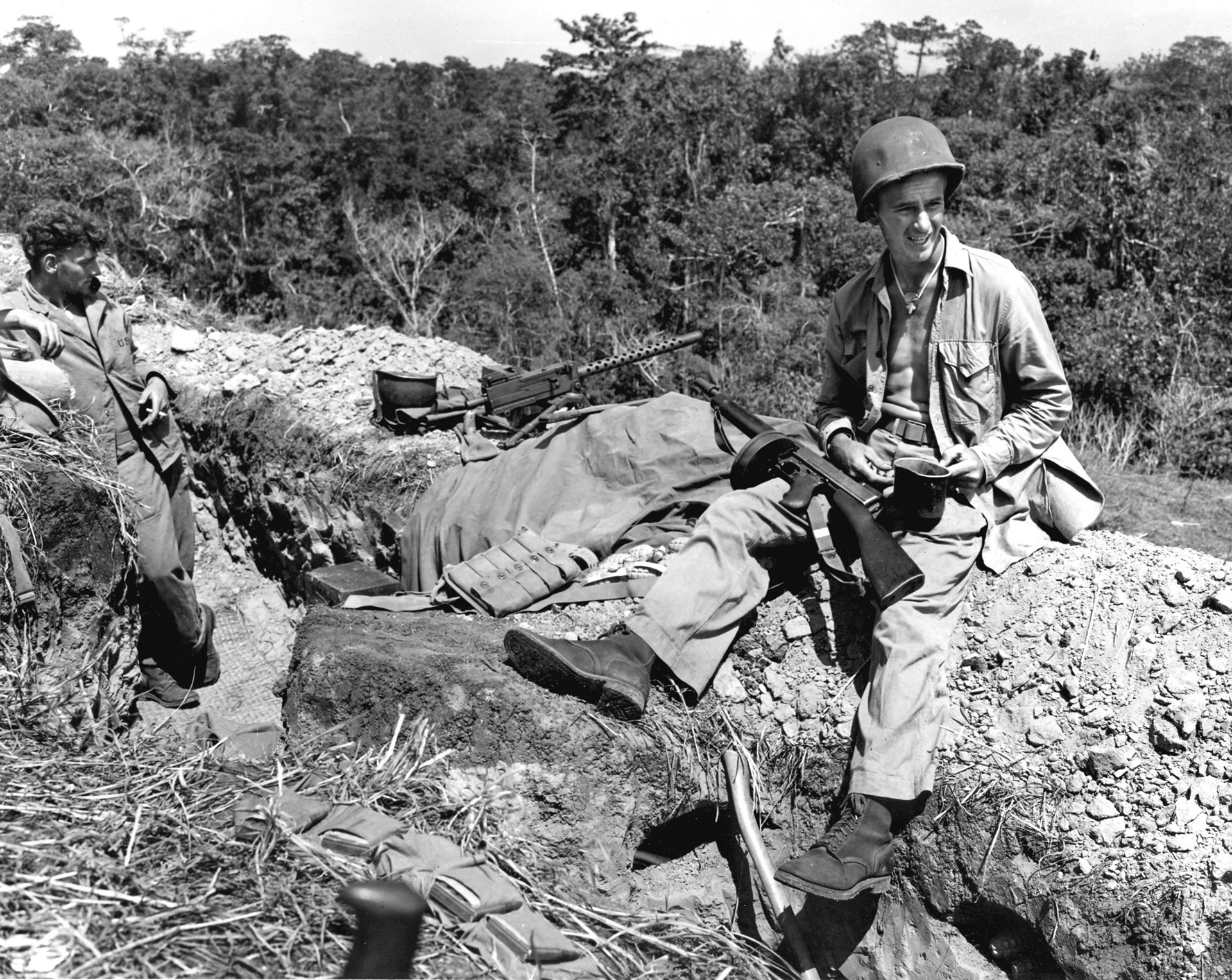

As America entered World War II in the Pacific theater after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Marine Corps sought to form an elite fighting force from their already above-average ranks. This group became the Raiders, incorporating the toughest, most skilled, and most motivated men in the Corps. Led by unconventional thinkers like Evans Carlson and the quiet-but-intense “Red Mike” Edson, the Raiders entered combat in places with soon-to-be-famous names, such as Makin Island and Guadalcanal. They conducted the “Long Patrol” on Guadalcanal, sowing chaos behind enemy lines and contributing to the defeat of the Japanese there. Eventually, however, the needs of the war effort and internal discomfort about elite units led to the Raiders’ disbandment and incorporation into the new 4th Marine Division.

The Raiders are among the lesser known of America’s early Special Forces organizations, but books such as this new title are shedding light on their exploits. The book has an easy, flowing narrative that pulls the words of Raider veterans into the author’s own clear prose. Overall, the work does credit to the Raider legacy, giving the reader a detailed summary of the unit’s contribution to victory in the Pacific.

Asian Armageddon 1944 – 1945: War in the Far East (Peter Harmsen, Casemate Books, Havertown, PA, 2021, 237 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

Asian Armageddon 1944 – 1945: War in the Far East (Peter Harmsen, Casemate Books, Havertown, PA, 2021, 237 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

During the last 20 months of World War II, the Allies essentially beat the Japanese Empire into submission. A series of far-ranging operations eliminated Japan’s ability to wage meaningful war. At sea, the United States Navy crippled their opponent’s naval power while it simultaneously destroyed Japan’s merchant fleet in history’s only successful submarine campaign. While the Americans conducted amphibious invasions of Japanese-held islands, the United Kingdom held and then pushed back the Japanese in Southeast Asia. Meanwhile, though they seldom receive credit for it in the West, Chinese forces kept large members of Japanese troops pinned on the Asian mainland. Once the Soviets entered the war and two atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war finally ended.

The author is a renowned journalist, with two decades of experience in Asia. This third book in his trilogy on the Pacific War concludes the series by effectively showing how wide-ranging the war truly was, involving more than just the Americans and Japanese. The book also covers the actions of various allies and the war’s effects on civilian populations. The maps are well done, and the photograph insert contains many iconic and dramatic images.

The Tanks of Operation Barbarossa: Soviet Versus German Armour on the Eastern Front (Boris Kavelerchik, translated by Stuart Britton, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2021, 280 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, softcover)

The Tanks of Operation Barbarossa: Soviet Versus German Armour on the Eastern Front (Boris Kavelerchik, translated by Stuart Britton, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2021, 280 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, softcover)

When Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Soviets had four times as many tanks as the Germans. Some of their tanks were considered of superior design to the panzers, yet the Soviet tank force suffered horribly in the first weeks of the invasion. Thousands of Soviet tanks were destroyed or captured, with many of them abandoned by their crews. Even the T-34 and KV-1 models, with their effective armor protection and armament, achieved only limited successes in local operations. Failure in the Soviet armored forces proved widespread at the beginning of the war.

This new book explains the reasons for the Soviet failure and compares the tanks, tactics, and training of the two armies. The author delves into the reasons for poor Soviet battlefield performance, such as poor communications, a lack of training, unreliable tanks with a lack of spare parts and logistical support, and bad leadership at multiple levels. He uses case studies to show how these factors affected the chance of success in combat. The book also demonstrates how both armies used combined-arms tactics, but with varying degrees of success. There are many good graphics and charts relating added information and comparing German and Soviet tanks, as well as an extensive set of detailed appendices.

Hitler’s War in Africa 1941 – 1942: The Road to Cairo (David Mitchelhill – Green, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2021, 242 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $42.95, hardcover)

Hitler’s War in Africa 1941 – 1942: The Road to Cairo (David Mitchelhill – Green, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2021, 242 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $42.95, hardcover)

Leutnant (Lieutenant) Ralph Ringler recalled excitement when he learned he had been assigned to the Afrika Korps. “In Africa there waited great adventure,” he stated. It seemed an elite unit, deploying to the desert to save the Italians from certain defeat at the hands of the British. In reality, the Afrika Korps was hastily organized, had little specialized equipment for desert operations, and lacked training or experience. Sand got into everything, penetrating filters and shortening the lives of engines. Soldiers had to trade with the Italians for proper uniforms and were not only unprepared for the daytime heat, but also the nighttime cold. Nevertheless, they attacked, pushing the British back everywhere except Tobruk. They continued to fight a back-and-forth struggle, maneuvering through the desert almost like fleets at sea, for the next two years.

Many books have been written about the war in North Africa. This one is exceptional due to its clear prose, well-organized narrative, and the author’s clever and liberal use of veteran accounts to place the reader’s mind in the events described. The photographs in the insert are well-chosen, showing figures from generals to privates and including graphic post-battle scenes and personal photographs of soldiers living in desert conditions. Maps set the reader into the major battles.

New and Noteworthy

Saipan 1944: The Most Decisive Battle of the Pacific War (John Greehan and Alexander Nicoll, Frontline Books, 2021, $22.95, softcover) The invasion of the Japanese-held island of Saipan paved the way for B-29 bomber attacks against the Japanese homeland. This photobook reveals the bitter struggle for Saipan in mid-1944.

Saipan 1944: The Most Decisive Battle of the Pacific War (John Greehan and Alexander Nicoll, Frontline Books, 2021, $22.95, softcover) The invasion of the Japanese-held island of Saipan paved the way for B-29 bomber attacks against the Japanese homeland. This photobook reveals the bitter struggle for Saipan in mid-1944.

Battle for the Bocage Normandy 1944 (Tim Saunders, Pen and Sword Books, 2021, $42.95, hardcover) This book chronicles the battles for Point 103, Tilly-Sur-Suelles, and Villers-Bocage during the summer of 1944. German panzer divisions struggled against British units brought to Europe from the Mediterranean.

German Tank Destroyers (Pierre Tiquet, Casemate Books, 2021, $39.95, hardcover) Germany used several obsolete tank chassis and modified current designs to field a wide variety of self-propelled tank destroyers. This book uses a combination of illustrations and veteran accounts to show how they were used in combat.

The Finnish-Soviet Winter War 1939-40: Stalin’s Hollow Victory (David Murphy, Osprey Books, 2021, $24.00, softcover) The Finns put up stiff resistance to the Soviet invasion, inflicting heavy casualties. Eventually, however, the weight of Soviet numbers swamped the Finns, forcing their capitulation.

Stalin’s Armour 1941-1945: Soviet Tanks at War (Anthony Tucker-Jones, Pen and Sword Books, 2021, $34.95, hardcover) At the beginning of the war, the Soviets lost thousands of tanks despite a vast numerical superiority. By the end, they were able to launch massed, coordinated armored attacks.

Stalin’s Armour 1941-1945: Soviet Tanks at War (Anthony Tucker-Jones, Pen and Sword Books, 2021, $34.95, hardcover) At the beginning of the war, the Soviets lost thousands of tanks despite a vast numerical superiority. By the end, they were able to launch massed, coordinated armored attacks.

The Liberation of the Philippines (Jon Diamond, Pen and Sword Books, 2021, $28.95, softcover) This photobook contains hundreds of images of the campaign to liberate the Philippine Islands from Imperial Japan. Descriptive text accompanies each photograph.

Battle of Peleliu 1944: Three Days that Turned into Three Months (Jim Moran, Frontline Books, 2021, $24.95, softcover) The Americans expected to capture Peleliu in three days. This photobook’s imagery helps explain why it took so much longer.

Holland 1940: The Luftwaffe’s First Setback in the West (Ryan K. Knoppen, Osprey Books, 2021, $24.00, softcover) The Luftwaffe’s strategy against Holland was supposed to bring victory in a day. Instead, they had to resort to five days of terror bombing to force a surrender.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments