By Al Hemingway

On Sunday morning, October 23, 1983, a large yellow Mercedes-Benz truck was seen approaching the Beirut International Airport. No one paid particular attention until the vehicle began to pick up speed and make its way toward the Battalion Landing Team (BLT) Headquarters building of the 1st Battalion, 8th Marines.

The truck then passed through a wrought-iron gate, rammed into a sandbagged sentry position, and crashed through another barrier before ending up in the lobby of the four-story structure. What happened next was almost indescribable. The truck, loaded with explosives, detonated with a force later described as the equivalent of 12,000 pounds of TNT. The massive, seemingly indestructible concrete building was reduced to rubble within a matter of seconds.

The truck then passed through a wrought-iron gate, rammed into a sandbagged sentry position, and crashed through another barrier before ending up in the lobby of the four-story structure. What happened next was almost indescribable. The truck, loaded with explosives, detonated with a force later described as the equivalent of 12,000 pounds of TNT. The massive, seemingly indestructible concrete building was reduced to rubble within a matter of seconds.

And 241 American servicemen lay dead.

At the time, it was the worst act of terrorism ever recorded against Americans. How could this tragedy have occurred? In his new book, Peacekeepers at War: Beirut 1983: The Marine Commander Tells His Story (Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2009, 256 pp., maps, photos, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover), Colonel Timothy J. Geraghty, USMC (Ret.), the senior ground commander on the scene, gives an in-depth account of the tragic event, which stands as a forerunner of more than 25 years of Islamic violence against American and other western nations.

The Marines, together with French and Italian contingents, first arrived in Beirut, Lebanon, in the summer of 1982. They returned that fall after the horrific massacre of 700 Arab men, women, and children in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camps by Phalangist Christian militiamen. This was the impetus of the peacekeeping mission that followed. Originally, the directive from the Joint Chiefs of Staff read: “To establish an environment which will permit the Lebanese Armed Forces to carry out their responsibilities in the Beirut area.” It was troublingly vague.

“The mission from the start was opaque, nebulous,” writes Geraghty. “But when you look at this sort of mission in terms of what we all learn as Marines, it flies in the face of our doctrine. The decision to send us in was made with good intentions, but it was made from the heart rather than from the facts.”

As the commander on the ground, Geraghty accepts full responsibility. He makes it clear, however, that outside events took place that dramatically altered his unit’s primary objective as neutral peacekeepers. First, the Israeli Defense Force withdrew from its positions near the Shouf Mountains. Their early departure left a void that had to be filled by the Lebanese armed forces. Immediately following the Israeli departure, rocket, mortar, and small-arms fire increased between all the factions. The Marines began to sustain casualties, and their role as peacekeepers was transformed into becoming active combatants in the conflict.

“This regretful decision by Israeli leaders predictably accelerated the resumption of the Lebanese civil war,” Geraghty writes, “culminating in the dual suicide truck attacks on the multinational peacekeeping force six weeks later.”

Naval gunfire and air strikes were authorized by the United States in direct support of the LAF. Geraghty did his utmost to stop the requests. He and the other American commanders on the scene thought the White House was overreacting to the situation. Despite discussions with liaison officers from Ambassador Robert “Bud” McFarlane’s staff, Geraghty’s pleas fell on deaf ears and the fire support missions continued. Geraghty told McFarlane pointblank: “This will cost us our neutrality. Don’t you realize that we’ll get slaughtered down here? We’re sitting ducks.”

Geraghty points out lessons that should have been learned from the assault on the BLT barracks, especially the creation and ultimate buildup of Hezbollah, the extremist group responsible for the suicide truck attacks. This fanatical organization is still supplied and trained by the Iranian and Syrian governments. It also has close ties with Al-Qaeda and offers to train terrorists for operations against Israel and the United States.

Because of our “passive response,” Geraghty believes, the “enemy smelled blood,” and struck at the American homeland on September 11, 2001. There was no retaliation for the 1983 bombings, nor have any of the perpetrators been brought to justice for their heinous crime. Geraghty’s book is an eye-opener for anyone who wants to learn more about what happened in 1983 before and after the awful destruction of the Marine barracks in Beirut.

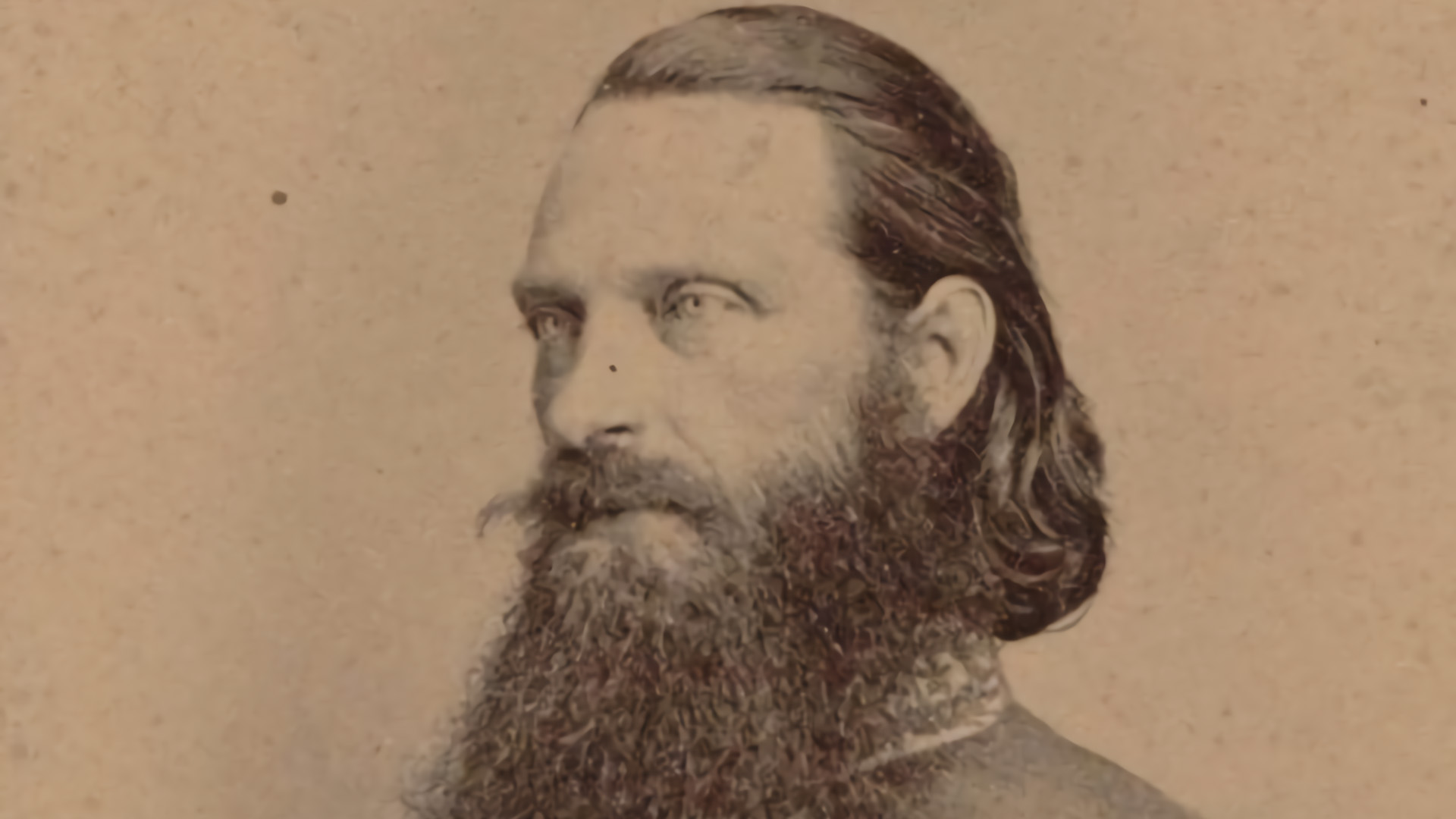

Jerusalem’s Traitor: Josephus, Masada, and the Fall of Judea by Desmond Seward, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2009, 314 pp., photos, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Jerusalem’s Traitor: Josephus, Masada, and the Fall of Judea by Desmond Seward, DaCapo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2009, 314 pp., photos, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Acclaimed historian Desmond Seward has taken a rather complicated era in world history and has penned an extraordinary biography of Josephus, a Jewish general at the time of the revolt against Rome in ad 66.

Josephus was born into a wealthy and influential family. He was appointed a general during the rebellion in Galilee against the Romans who occupied Palestine at that time. During the seizure of Jotapata, he was taken prisoner. Always a resourceful man, he escaped certain death by prophesying to the Roman commander, Titus Vespasian, that he would become emperor of Rome, a prediction that did come true.

Josephus traveled with Vespasian’s legions and was an eyewitness to the destruction of his homeland. When Vespasian’s son Titus assumed command of the expeditionary force after his father’s ascent to the throne, it was Titus who eventually laid siege to Jerusalem. Although Titus tried not to destroy the temple, the Jewish Zealots inside, whom Josephus loathed, left him no alternative.

After the insurrection was crushed, Josephus returned to Rome and wrote about his experiences in the conflict. His works, which have created intense debate among scholars throughout the years as to their historical accuracy, included The Jewish War, Vita, and his voluminous Antiquities of the Jews. Although he took the name Flavius Josephus and became a Roman citizen, he never forgot his Jewish faith and upbringing. His last account, Contra Apionem, was published after he died around ad 95.

Seward does a masterful job at dissecting Josephus’s works to separate his prejudices and exaggerations and give the reader an accurate account of what happened during a turbulent time in Jewish history when thousands perished, not only at the hands of the Romans but also by the own countrymen.

Despite his boastful writing and obvious disdain for the Zealots (with the exception of their heroic stand at Masada), Josephus’s The Jewish War provides an excellent glimpse into an important part of Israel’s past. Considered arrogant and deceitful by many because of his collaboration with the enemy, Josephus deserves praise, Seward writes, for his staunch belief in the continuation of the Jewish faith. “We have lost our land and our dearest possessions,” Josephus wrote, “but our Law will live forever.”

The Darkest Summer: Pusan and Inchon 1950: The Battles That Saved South Korea–and the Marines–From Extinction by Bill Sloan, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2009, 545 pp., photos, notes, index, $27.00, hardcover.

The Darkest Summer: Pusan and Inchon 1950: The Battles That Saved South Korea–and the Marines–From Extinction by Bill Sloan, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2009, 545 pp., photos, notes, index, $27.00, hardcover.

When the U.S. Marines triumphantly raised the Stars and Stripes on Mount Suribachi at Iwo Jima on February 23, 1945, Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal boasted to Lt. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith: “Holland, the raising of that flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next 500 years.”

Little did Forrestal know that by 1947 the illustrious Marine Corps would be fighting for its very existence—not on any remote battlefield, but within the hallowed halls of Congress, the Pentagon, and even the White House. And it would take another war to ensure their survival as America’s premier fighting force.

Many within the Army and Navy wanted to integrate the Marines’ mission within their branches. Some politicians, including President Harry S. Truman, agreed. He continually refused to appoint the commandant of the Marine Corps to the Joint Chiefs of Staff, declaring: “The Marine Corps is the Navy’s police force, and as long as I am president, that’s what it will remain. They have a propaganda machine that’s almost equal of [Soviet Premier Joseph] Stalin’s.”

Despite this stinging slap, the Marine Corps was saved from being disbanded through the efforts of Michigan congressman Clare Hoffman, Commandant General Alexander A. Vandegrift, Brig. Gen. Gerald Thomas, Lt. Col. Victor “Brute” Krulak, and Brig. Gen. Merritt A. Edson. The Marine Corps was assured its mission when Hoffman added amendments to the National Security Act. On July 25, 1947, Truman signed the bill into law.

Then came June 25, 1950. The North Korean People’s Army suddenly invaded South Korea and drove deep into the country, capturing Seoul and sending the South Korean and American armed forces reeling in retreat. Woefully undermanned and ill-equipped, the 24th and 1st Cavalry Divisions were rushed to the war zone to stem the tide of the enemy advance. The Marines hastily formed the 1st Marine Provisional Brigade under Brig. Gen. Edward A. “Eddie” Craig, a combat-savvy leatherneck who fought brilliantly in the southeastern pocket of the country known as the Pusan Perimeter.

General Douglas MacArthur’s masterstroke at Inchon soon followed. Despite the terrible tides in the harbor and the nervous pleas from his staff, MacArthur had the Marines land at Inchon and cut off the NKPA forces in the region. It would prove to be one of the greatest amphibious assaults in history. Even at the Chosin Reservoir, when thousands of Chinese troops entered the conflict, the Marines performed magnificently by withdrawing slowly, maintaining unit integrity and taking their dead and wounded with them.

Their outstanding performance during the Korean War assured the Marines’ central role within the American military establishment. Never again would any politician suggest eliminating the Marine Corps after it had proved once more to be America’s foremost amphibious force in readiness and lived up to the Corps’ proud motto: “First to Fight.”

Seal Warrior: Death in the Dark: Vietnam 1968-1972 by Master Chief Thomas H. Keith, USN (Ret.) and J. Terry Riebling, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, 2009, 292 pp., photos, index, $25.99, hardcover.

Seal Warrior: Death in the Dark: Vietnam 1968-1972 by Master Chief Thomas H. Keith, USN (Ret.) and J. Terry Riebling, Thomas Dunne Books, New York, 2009, 292 pp., photos, index, $25.99, hardcover.

As their name implies, United States Navy SEALs have fought on sea, land, or air since their inception in 1962. Highly trained in guerrilla and unconventional warfare, SEAL teams strike deep inside enemy territory to gather valuable intelligence data and keep the enemy off balance.

Keith was a member of SEAL Team-2 on numerous tours in Southeast Asia. He comes from a long lineage of warriors in his own family dating back to the Revolutionary War. Military service and combat runs in Keith’s blood, and his 29 years of experience in counterinsurgency operations makes him more than qualified to tell this story.

“The SEAL Teams will soon celebrate our first fifty years of service, and while we have grown, learned new skills, and taken on more dangerous and demanding duties, not much has changed,” writes Keith. “Every warrior who served in the teams, and who serves in them today, carries on a tradition and a warrior ethic that remain unequaled. The only easy day was yesterday.”

The End of Empire: Attila the Hun & the Fall of Rome by Christopher Kelly, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2009, 350 pp., illustrations, index, $26.95, hardcover.

The End of Empire: Attila the Hun & the Fall of Rome by Christopher Kelly, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2009, 350 pp., illustrations, index, $26.95, hardcover.

The word Hun can still conjure up images of bloodthirsty and ruthless savages, bent on destroying everything in their path. In their savage heyday, the Huns sacked numerous cities and towns as they inched their way toward the greatest prize of all—the Eternal City, Rome.

Leading this band of nomads was their charismatic and often brutal leader, Attila. History has not been kind to the king of the Huns. He is portrayed as an uncivilized brute, murdering and pillaging anyone he encountered. Some claim he was the primary reason that the Roman Empire finally crumbled. Others believe that, although Attila certainly contributed to the downfall of the Roman Empire, it was doomed long before he arrived on the scene, dying from its own internal corruption.

Kelly believes that Attila the Hun must be placed in the proper historical context. There is no doubt that he ransacked, murdered, and burned villages to the ground. Kelly is quick to point out, however, that other nomadic tribes such as the Vandals and Goths did much the same. He portrays a somewhat kinder and gentler Attila as a shrewd negotiator and perceptive person in spite of his wrongdoings.

Attila’s premature death left a void in the Hun leadership. Soon, the “wolves from the North” disappeared and left no trace. The once-mighty Roman Empire, now fragmented, would eventually become the countries of France, Italy, and Spain. In a way, the Hun invasion of northern Italy and France was the unintended springboard for the formation of modern-day Europe.

Manila and Santiago: The New Steel Navy in the Spanish-American War by Jim Leeke, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 190 pp., photos, index, $26.96, hardcover.

Manila and Santiago: The New Steel Navy in the Spanish-American War by Jim Leeke, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2009, 190 pp., photos, index, $26.96, hardcover.

The Spanish-American War, though brief, was a shining moment in American military annals. “It has been a splendid little war; begun with the highest motives, carried on with magnificent intelligence and spirit, favored by that fortune which loves the brave,” said John Hay, U.S. ambassador to England, at the time.

Despite the dubious reasons that catapulted the United States into hostilities with Spain in 1898, Hay was correct on one point—there was a magnificent spirit displayed by American troops, particularly those in the U.S. Navy. Time and time again, naval officers demonstrated indomitable courage and sheer audacity when confronting the much-larger enemy.

On May 1, 1898, Commodore George Dewey inflicted a humiliating defeat on the Spanish fleet commanded by Admiral Patricio Montojo in the Philippines. Directing his men aboard his flagship USS Olympia, Dewey smashed the enemy within seven hours without suffering a single fatality. In addition, he seized Manila Bay, establishing the United States as a world power for a century to come.

Several months later, in the waters off Cuba, the warships of Rear Admiral William T. Sampson and the flying squadron headed by Commodore Winfield Scott Schley met the enemy at the Battle of Santiago Bay. When the smoke cleared, the Spanish fleet had suffered numerous hits and 500 casualties. The catastrophic defeat signaled the end of a Spanish naval presence in the Western Hemisphere.

Leeke’s book vividly describes the people and events surrounding both of these important victories during the short but bloody conflict. Many of those in government, including President Theodore Roosevelt, made a concerted effort to build up the American Navy after realizing what a strong fleet could accomplish, and it was because of men like Sampson, Dewey, and Schley that the Navy remains a formidable fighting force to this day.

Taking Command: General J. Lawton Collins from Guadalcanal to Utah Beach and Victory in Europe by H. Paul Jeffers, Caliber Books, New York, 2009, 325 pp., photos, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Taking Command: General J. Lawton Collins from Guadalcanal to Utah Beach and Victory in Europe by H. Paul Jeffers, Caliber Books, New York, 2009, 325 pp., photos, index, $25.95, hardcover.

He was known as “Lightning Joe” Collins to his men. He led by example, trying to visit the front as much as possible. He came ashore with the 25th Division to relieve the Marines on Guadalcanal in early 1943 and did such an exemplary job that he was subsequently reassigned to the European Theater.

Collins was given the task of heading the Seventh Corps that landed on Utah Beach. Under his leadership, the corps took part in closing the Falaise pocket to cut off the retreating German Army. His units were involved in the bitter battles at Aachen and the Hürtgen Forest during the bloody Battle of the Bulge in the bone-chilling winter of 1944-1945. Collins’s troops eventually entered the all-important Ruhr Valley, the heart of German industry for the war effort, and participated in numerous battles and skirmishes until war’s end in May 1945.

Called the “GI’s general” by correspondents, Collins often appeared on the front lines. During the fighting on New Georgia in the Central Solomons, he occupied 15 different foxholes in one evening. Collins eventually became Army Chief of Staff, assisted in the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and was appointed ambassador to South Vietnam in 1954 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He suffered a fatal heart attack at the age of 91 in 1987.

Jeffers’s book is a fitting tribute to a true fighting man who inspired his troops and possessed excellent leadership skills. “Such self-assurance is tolerable only when right,” wrote General Omar Bradley in his autobiography A Soldier’s Story, “and Collins, happily, almost always was.”

In the Company of Generals: The World War I Diary of Pierpont L. Stackpole edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 2009, 208 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $34.95, hardcover.

In the Company of Generals: The World War I Diary of Pierpont L. Stackpole edited by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO, 2009, 208 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $34.95, hardcover.

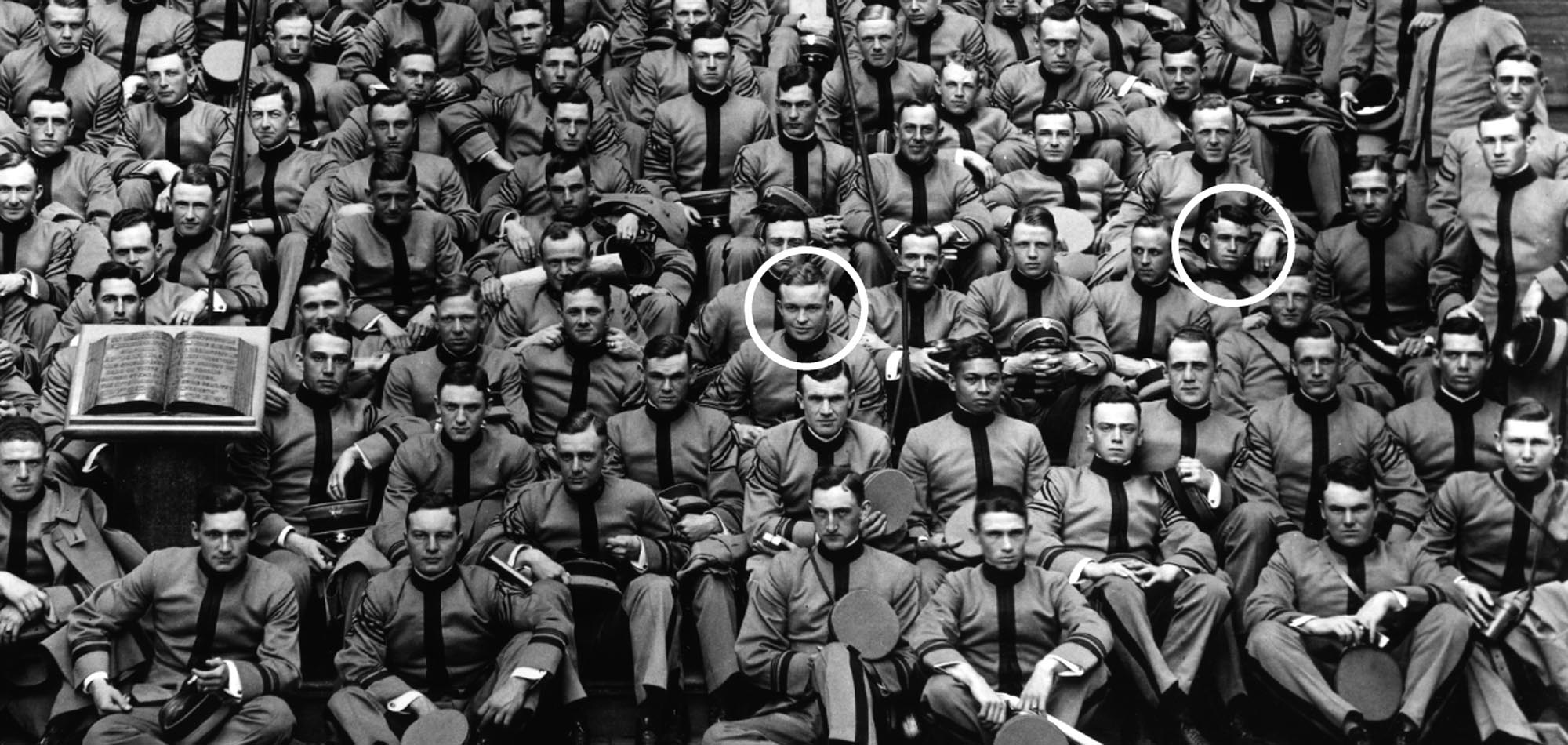

A blueblood Boston lawyer by trade, Pierpont L. Stackpole was thrust into action at the outset of World War I. He was commissioned a major, and later became a lieutenant colonel and an aide to Maj. Gen. Hunter Liggett. In that latter role, Stackpole was in a position to observe firsthand Liggett’s remarkable leadership qualities.

A Pennsylvanian by birth, Liggett graduated from West Point in 1879 and served in a variety of remote western outposts at the beginning of his career. Promotions during the era were slow in coming, but Liggett persevered and by the beginning of World War I he had attained the rank of major general. Despite his portly appearance, Liggett had a keen mind. Realizing his enormous military knowledge and common sense, American Expeditionary Force Commander General John J. Pershing appointed Liggett the leader of the Army Corps. By the time of the Meuse-Argonne Campaign, the bloodiest battle in the war, he had become commander of the First Army.

Liggett’s no-nonsense leadership capabilities were much evident during his time in France. Described as a “shadowy figure” by the author because he was never really in the limelight, Liggett’s tremendous contribution to training the largest American Army to date was put into proper perspective by Stackpole. The young Harvard graduate traveled with Liggett almost everywhere and observed firsthand his methods. Liggett discussed his generals, the war and other subjects during their quiet moments together.

Stackpole’s journal is an important document that sheds much-needed information about a crucial time in American mililtary history. Never before had American senior officers commanded such large amounts of men in battle, and it was Hunter Liggett who played a significant role in making sure that it was done right.

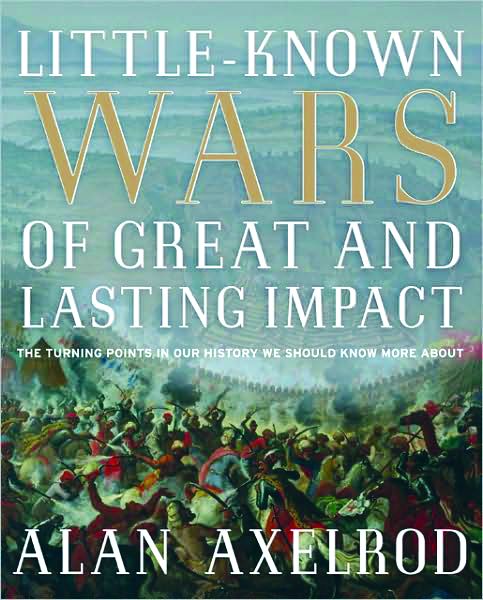

Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact by Alan Axelrod, Fair Winds Press, Beverly, MA, 2009, 288 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $19.99, softcover.

Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact by Alan Axelrod, Fair Winds Press, Beverly, MA, 2009, 288 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $19.99, softcover.

From the beginning of recorded history, there has been only 292 years of peace. Wars, great and small, have been all too often the rule. Axelrod’s book looks at 18 different small wars that have had an everlasting impact on the world. Beginning with the revolt of the Iceni Queen Boudicca in ad 60 and stretching to the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya from 1952 to 1956, the author gives a brief synopsis of each war.

One good example is a war that took place in North America that clearly altered America’s history. King Philip’s War, waged from 1675-1676 in New England, was America’s costliest conflict, according to Axelrod. Fifty percent of existing white villages were severely damaged, and 12 were razed to the ground. The economy suffered as well. The war cost an estimated 100,000 pounds and devastated the trade and fishing in the region.

More importantly, the war was terrible in the cost of human life. The population of New England at that time was a mere 30,000. Six hundred died in the fighting, with hundreds of additional deaths recorded among the civilian population due to disease, starvation, and other illnesses directly attributable to the war.

King Philip’s War “set the fierce tone of white-Indian relations in the United States,” writes Axelrod. From this came the French and Indian War and other violent encounters between whites and Indians that would culminate in the massacre at Wounded Knee more than two centuries later.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments