By Martin Dougherty

The winter of 1944-45 saw Nazi Germany in a grim position. The Allies were well established in Europe and advancing quickly. Their main obstacle was logistics; to maintain the offensive, huge quantities of troops and supplies had to be brought up. This required control of deep-water ports as close to the front as possible. The capture of Antwerp, Belgium, gave the Allies what they needed, though it was not until November 1944 that it became operational. With supplies flowing in every day, Axis commanders could only wait for the inevitable large-scale assault. It would come when the Allies were ready and would fall where they chose.

The German defenses of the Siegfried Line, established in the 1930s, were theoretically formidable but were designed with 1930s weapons and tactics in mind. Equipment had been removed for use elsewhere, and parts of the fortifications were in disrepair. An urgent project, beginning in August 1944, was undertaken to reactivate the defenses, but it was clear the “Westwall” was not the impenetrable obstacle Hitler had hoped it would be. He had triumphantly declared himself the greatest fortress builder of all time upon the completion of the Siegfried Line, but now it was manned with semi-invalids such as the “stomach” and “leg” battalions.

With passive defense certain to bring eventual defeat, the only option was to take the offensive. The Axis plan was over-ambitious, but while a more limited offensive might bring about a local victory, it could not alter the strategic balance. Thus, the Nazi offensive in the Ardennes region would be an all-or-nothing affair. If German forces could smash through the lightly held Ardennes and advance as far as Antwerp, Allied logistics would be thrown into chaos.

Exactly what the Axis leadership thought would be achieved is open to debate. So long as the war was not completely lost, there might be a chance for a negotiated peace, a falling-out between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union, or the deployment of some new weapon that could alter the course of the war. Perhaps strategic thinking came down to nothing more than the choice between accepting defeat and trying to win—no matter how slim the chances. Those who argued for a more limited offensive were brushed aside. Antwerp must be taken; any lesser outcome was meaningless in the long run.

The offensive was launched on December 16, 1944. It had the advantage of surprise, but few others. Short of fuel, the armoured spearhead would have to capture sufficient supplies to continue. Air support and even reconnaissance were extremely limited. Despite significant successes, the advance eventually stalled, and attempts to get it moving again were unsuccessful.

Having failed to achieve their strategic objective in the West, the Axis forces withdrew. Some went into defensive positions along the Siegfried Line while the best formations were sent east in response to a new Soviet offensive.

The Ardennes Offensive was a disaster for the German forces. Large numbers of tanks and armoured vehicles were lost, many of them abandoned after running out of fuel. There would be no further large-scale Axis operations in the West, but fuel was the motivation for their final offensive of the war—Operation Spring Awakening.

The situation in the East was equally disastrous. The Red Army made rapid gains throughout the summer of 1944, destroying some Axis formations and forcing others into a hasty retreat to avoid encirclement. A successful offensive in Romania during August 1944 inflicted further losses on Axis forces and triggered Romania’s defection to the Allies. This deprived Germany of its main source of oil. All that remained was located in southern Hungary, and its loss would leave only the operational synthetic-oil production sites, which were high-priority targets for Allied air attacks.

The Soviet offensives made huge gains but ultimately ground to a halt. Logistics, as always, was a factor, and there may also have been political considerations. It is probable that the Soviets chose to slow down their advance when they received word of the Warsaw Uprising. If so, this was a cynical gambit which granted the German occupation forces time to put down the uprising before the Red Army drove them out. Rather than arriving at a self-liberated national capital the Soviets took possession of occupied territory, with grave implications for the future of Poland.

After the advances of the summer, the Red Army had paused to regroup and build up for a renewed offensive in the winter. This may have been a factor in the German decision to launch the Ardennes Offensive. Operating on interior lines of communication, it might be possible to lunge against one threat then the other, buying time for the transfer of forces with victories in the field.

The Soviet offensive opened on January 12, 1945, a little earlier than originally planned. The extent of the German commitment in the Ardennes offered a window of opportunity that Soviet commanders were keen to exploit. The operation was highly successful, with some Axis formations effectively destroyed and others forced into precipitate retreat. By the end of the month, the Red Army had reached the River Oder with no significant resistance between its lead elements and the Nazi capital of Berlin.

A halt to reorganize was again necessary, and with significant German forces active in Pomerania, the northern flank of the Red Army advance was exposed. Further movement was not possible for nearly two months, giving Axis forces a chance to transfer reserves for the coming Battle of Berlin. This was one reason for the termination of the Ardennes Offensive—the only available troops had to be first pulled out of action on the Western front.

Despite the obvious threat to Berlin and strong arguments for a concentration of forces to counter it, access to fuel was the more pressing strategic concern. Plans to defend the capital were put into practice, focusing on a defensive line at the Seelow Heights, and measures undertaken to flood low-lying areas.

It was logical that the best mobile and armored forces should be sent to assist in this defense, but instead they were deployed elsewhere. An attack on the Hungarian oilfields would spell the end of the German war effort, whether or not Berlin was captured. Thus, Operation Spring Awakening was conceived: a bold counteroffensive to protect the vital oil supplies.

In addition to the large gains made in the north, Soviet forces pushed toward Hungary in late 1944. By December, the Red Army had reached the River Danube, which presented a significant obstacle. A German counterattack prevented an immediate crossing, buying time to set up defensive lines from Budapest to Lake Balaton. These were collectively known as the Margarethe Positions.

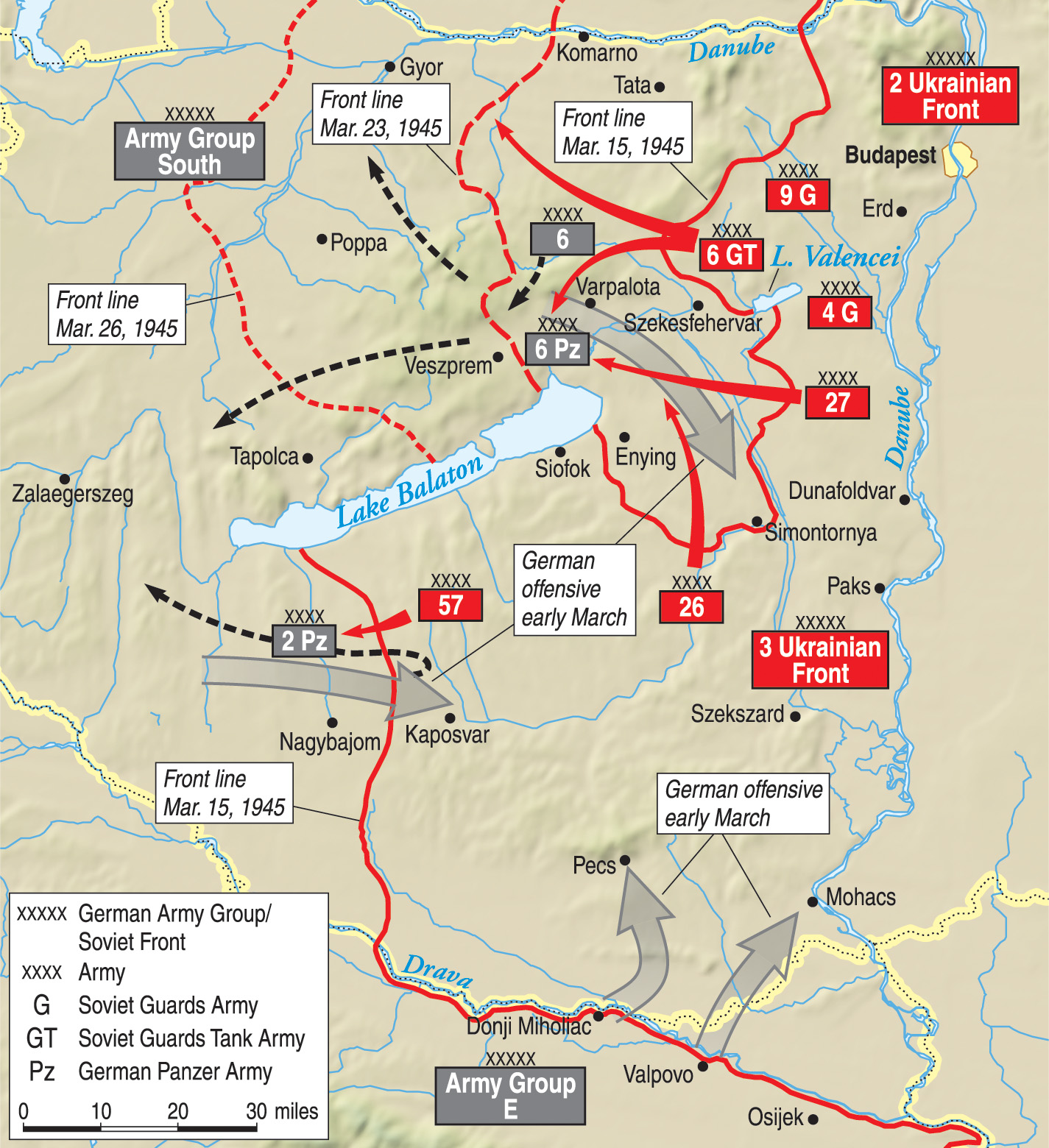

The Soviet 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts were tasked with taking Budapest. (A Front in Soviet parlance was the equivalent of a German Army Group.) This force succeeded in establishing a bridgehead across the Danube at Gran and besieged Budapest, which fell on February 12, 1945. This opened the way for an offensive toward Vienna and the Hungarian oil-producing region around Nagykanizsa. German senior commanders hoped that Spring Awakening would prevent this by destroying the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts while liberating Budapest in the process.

The area chosen for Operation Spring Awakening was the responsibility of Army Group South, under the command of General Otto Wohler. Army Group South had previously been designated Army Group South Ukraine, changing designation in September 1944. Wohler took command in December 1944, gaining control over a mix of German and Hungarian army units. Many of these had suffered heavy casualties in the previous fighting, and the force as a whole was not up to the requirements of the coming offensive.

The lead role in the Spring Awakening counteroffensive was given to 6th Panzer Army, under the command of Oberstgruppenfurher Joseph “Sepp” Dietrich. Originally created as a regular army formation, 6th Panzer Army was composed largely of SS units, but even these contained a great many regular army personnel. The force as a whole was finally transferred to the Waffen SS at the beginning of April 1945, but is generally recorded as being an SS formation due to the presence of major Waffen SS units and an SS commanding officer.

Sixth Panzer Army was pulled out of the Western theater and hurriedly refitted with a target finish date of January 30. It was not possible to bring the depleted formations back up to full strength in the time available, but every effort was made. Tanks and armored vehicles were delivered as they came off the production lines—echoing the desperate defense of Soviet cities earlier in the war—and were available in sufficient numbers to bring the panzer units more or less up to strength.

Personnel were scraped together from wherever they could be found—rear-echelon formations, wounded who had recovered sufficiently, and drafts “borrowed” from the navy and air force. Integrating these with the elite veterans of the existing force should have taken considerable time, but time was not available. The result was a force that looked formidable but might have serious flaws.

The move to the jumping-off points for Operation Spring Awakening was covered by a comprehensive deception operation that played to the Allies’ expectations. Some elements of the army, including heavy tanks, were initially moved in the direction of the defenses along the Oder. All units were given cover names, identifying them as formations unlikely to be associated with a major offensive. To prevent the deception being revealed, identifying marks were removed or covered.

The redeployment, though rapid, would take time, so preliminary operations were launched with local forces. These were intended to remove obstacles and lay the foundations for the coming offensive. In particular, it was necessary to counter the threat to Vienna and gain control of Budapest. To this end, the offensive would take the form of a two-pronged attack toward Budapest, cutting off Soviet forces in a repeat of the successful “kesselschlacht,” or battle of encirclement, of earlier campaigns.

The preliminary offensive thrusts were launched on January 18, 1945, and were initially successful. In the northern sector, rapid advances were made against relatively light opposition. This offensive reached a point about 10 kilometers from Budapest before being halted. In the southern sector, similar gains were made, and large Soviet forces were threatened with encirclement. The high point of the operation was January 26, after which Soviet counterattacks retook the lost ground.

On February 13, another offensive was mounted, this time aimed at eliminating the threat to Vienna. The I Panzer Corps was in position in time to participate in the attack, which was highly successful. Over the course of eight days the offensive cleared the threat and inflicted heavy casualties. This ensured the safety of Vienna, which was both politically and industrially important, but it revealed to the Soviets the presence of I Panzer Corps.

Allied intelligence services worked hard to keep track of major formations, and the implications of moving an elite force to Hungary were unlikely to be missed. Thus, the Soviets had some warning that a major offensive was likely and also now knew that the corps was not positioned to defend Berlin. A better approach would have been to keep I Panzer Corps out of this operation, concealing wider intentions and providing additional time for training.

Operation Spring Awakening was to be a pincer attack. The primary force, forming the northern arm of the pincer, was 6th Panzer Army supported by III Panzer Corps. This was part of 6th Army, which was under the command of General der Panzertruppe Hermann Balck and thus sometimes designated Armeegruppe Balck. The remainder of Balck’s force was positioned to secure the flank of the operation and provide reinforcements. The southern arm of the pincer was to be 2nd Panzer Army, which despite its name contained only a small proportion of armored units.

Second Panzer Army was not well suited to the task before it, as the majority of armored vehicles available to its formations were assault guns. These had proven effective in the right circumstances and were much easier to produce than tanks, but they were limited on the offensive or in fluid combat. Success or failure very much rested with 6th Panzer Army.

At this time the 6th Panzer Army was organized as two corps. The I SS Panzer Corps contained 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte and 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend; II SS Panzer Corps contained 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich and 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen. It was to be reinforced by I Cavalry Corps, containing the 3rd and 4th Cavalry Divisions. While described as cavalry, these were essentially mounted infantry units.

Various experiments during the war with mounted troops had produced mixed results, but on the Eastern front they had proven surprisingly effective. The cavalry formations were repeatedly reorganized and redefined, and sometimes misused by commanders who did not understand their particular style of warfare. Nevertheless, they made a valuable contribution to the defensive fighting in 1944 and participated in the attempt to relieve Budapest in the early weeks of 1945.

The two cavalry divisions had been defined as brigades until recently. Each comprised two regiments with some supporting troops. Both were redefined as divisions without receiving any significant reinforcement, largely to place their commanders on an equal level to infantry and armored officers. Thus, 6th Panzer Army nominally had six divisions, but two of these were more properly mounted infantry brigades.

The I Panzer Corps was to launch the opening movement of the offensive toward Dunafoldfar from a point near Lake Balaton, with II Panzer Corps on its left and the cavalry to the right. The 23rd Panzer Division, under Generalleutnant Joseph von Radowitz, stood in reserve. Meanwhile, III Panzer Corps was to drive toward Lake Valence. Its flank was to be secured by IV Panzer Corps, which was badly depleted from the earlier operations in the region.

In addition to the main pincer movement, an advance by Army Group E was to push across the River Drau from the south. Army Group E was not an armored formation, instead containing a mix of mountain troops and 11th Luftwaffe Field Division. The only armored unit was the heavily depleted 1st Panzer Division, which had suffered severe casualties acting as a response force in one crisis after another.

The Soviet commanders were aware that an offensive was being prepared and could predict its likely goals. They were planning their own offensive for mid-March with the intent of capturing Vienna. Four armies were allocated to this endeavor under the command of the 2nd and 3rd Ukrainian Fronts. Planning and preparations for the offensive went ahead, but a significant proportion of the available forces was reallocated to opposing the coming Axis attack.

It was apparent that the main German thrust was to be around the northern side of Lake Balaton and would therefore be opposed by the 3rd Ukrainian Front. This highly experienced formation had participated in offensives from the Ukraine to Romania and the Balkans and had resisted the German drive on Budapest in January. Under the command of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin, the Front was assigned three of the four available armies. Two were assigned the task of halting the German offensive, with one more in reserve.

The remainder of the available forces were assigned to the 2nd Ukrainian Front under the command of Marshal Rodion Malinovsky. If necessary, Malinovsky’s force could act as a final reserve to stop a thrust that somehow broke through the main defense line and the reserve army, but in the meantime, preparations for the Vienna offensive continued.

Facing the initial thrust were some seven infantry divisions, well-equipped with anti-tank guns and entrenched behind minefields. These were backed by a mobile reserve of tanks and self-propelled artillery. Although effective in mobile warfare, a large proportion of Tolbukhin’s armored forces were placed in defensive dispositions. Each armored brigade was to be the primary defense for a sector, with tanks and self-propelled artillery dug in to act as pillboxes. The Front’s motorized infantry component was broken down into battalions and assigned to support the armored brigades. The overall pattern was of combined-arms strongpoints capable of supporting one another, creating a defensive zone up to 30 kilometers deep in places.

Tank destroyers were positioned behind the front lines of strongpoints, but were also assigned advanced positions for use when necessary. Thus, as an armored attack developed, the tank destroyers advanced to their previously prepared positions and then fell back as the enemy closed. This played to the strengths of the tank destroyers without exposing them to fluid, close-range action, where turreted vehicles had the advantage.

These dispositions created a killing ground, which was made even more lethal by the creation of ambushes. Using decoys to attract the attention of enemy tank commanders, armored forces were concealed in positions from which they could attack the enemy’s flank or even rear. Although German reconnaissance for the offensive was generally good, these ambush forces were largely undetected at the beginning of the attack.

The initial attack was to be made over open country with a few ridges. It was expected that the ground would be frozen solid, but an early thaw was already creating dangerously muddy conditions. A request to postpone the operation until the ground had dried out was rejected, so 6th Panzer Army was forced to slog through mud and wet ground from the very start. Even reaching the assembly points was difficult, with some formations still out of position when the order to commence was given.

Despite protests from the commanders on the spot, Operation Spring Awakening launched on March 6, 1945. Sources disagree on exactly when, or even if, any given formation began its attack, but some events seem clear. The initial advance was preceded by an artillery barrage lasting 30 minutes, beginning at 4 am. Movement was made even more difficult by overnight snow and partial freezing of the ground of insufficient depth to permit easy movement.

Writing post-war, Sepp Dietrich describes how the mud trapped large numbers of vehicles, stating that he saw as many as 15 Tiger II heavy tanks sunk up to their turrets. Under these conditions vehicular movement was possible only along a few roads. Everywhere else the burden of the offensive fell upon the infantry.

The I SS Panzer Corps did make some progress but was able to advance less than 5 kilometers. The II Panzer Corps made no progress and might not have been in a position to attack at all on the first day. The Cavalry Corps put in an attack but was driven back by counterthrusts. The most promising result was an advance by III Panzer Corps, which threatened the Soviet flank. This prompted Marshal Tolbukhin to move reserves into the already-formidable defensive line.

The I SS Panzer Corps continued to push forward on the 7th, so that the Soviet 68th Guards Division was forced to withdraw. The 68th Guards fell back to defensive positions already occupied by its supporting formations and remained combat-ready.

The II SS Panzer Corps was able to begin its attack but made only a little progress on the second day of the offensive. Tanks that ventured off the few roads became stuck in deep mud, forcing their associated panzergrenadiers to advance without armoured support. Going was slow even on foot, and there was never any prospect of making much progress against the strong Soviet positions.

On March 8, the I SS Panzer Corps continued to push into the Soviet defences, but II SS Panzer Corps was still bogged down—literally and figuratively. Minor successes were scored by the panzergrenadier component, chewing their way laboriously into the enemy-defended zones, but for the offensive to succeed the Corps as a whole had to make rapid advances.

In an effort to get II SS Panzer Corps moving, the 23rd Panzer Division was ordered out of reserve and sent to join I Panzer Corps. Its mission was to exploit the gains made by I SS Corps in order to get into position to attack Soviet forces impeding II SS Panzer Corps. Meanwhile, I SS Panzer Corps continued to make gains on March 9th, with elements breaking through local positions in a series of forward lurches. Each one was halted when the next Soviet line was encountered. Tank destroyers played a notable part in these containments, forming a backstop each time behind which the retreating defenders could rally.

The Cavalry Corps was also successful on March 9. Unable to make a breakthrough on its own, it moved up through a gap in the enemy line created by I SS Panzer Corps. This permitted an exploitation more normally associated with armored forces. One division attacked enemy positions at Enying, while the other cut the road from there to Mezökomarom.

Although gains were finally being made, the offensive was increasingly dislocated. The inability of II SS Panzer Corps to keep up with the central force meant that the flank of the offensive was exposed to a counterattack. Some protection was afforded by the difficult conditions and the choice of avenues of attack. Notably, the River Sarviz and its associated waterways delayed Soviet forces getting into position for a counterattack, but this delay was temporary.

Despite a difficult start, the offensive had achieved enough to threaten the entire Soviet position. A rapid advance into their rear was a real possibility, while penetration of the defended zone created command-and-control problems. Marshal Tolbukhin’s solution was to reorganize his command, transferring control of units to commanders on either side of the breach. This permitted more coherent action against the intrusion and might forestall a collapse if further disruption followed.

Correctly identifying I SS Panzer Corps and its supporting cavalry as the main threat, Tolbukhin reinforced Twenty-Sixth Army with armored and anti-tank units. He requested permission to use the reserve armies, but was denied. Indeed, new orders arrived to launch a counteroffensive using these forces directed against the rear of 6th Panzer Army. The 3rd Ukrainian Front would lead this offensive with assistance from 2nd Ukrainian Front. This presupposed the Axis offensive could be halted, but while the situation was precarious, the Soviet forces still had deep defenses and a well-laid battle plan.

Despite the difficulties it faced, I SS Panzer Corps continued to advance throughout the day on the 10th. The 23rd Panzer Division launched an attack on Saregres. This was partially successful, in that it permitted the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte to force a crossing of the Sio canal. However, Saregres was not taken, and the division was unable to cross the canal to assist II SS Panzer Corps. The I Cavalry Corps also created a bridgehead on the Sio on March 10.

This left II SS Panzer Corps some 25 kilometers behind, still struggling to make any gains. This was not for lack of effort, but the Soviets had planned their defenses well. Attempts to flank impenetrable positions sent advancing forces into preselected ambush zones, where self-propelled artillery and anti-tank guns inflicted heavy losses.

The deadlock was broken on March 11 by the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, which put in a well-coordinated attack near Sarkeresztur. The II SS Panzer Corps was able to advance at last, while I SS Panzer Corps was still pushing ahead and spent that day clearing opposition from its flanks and securing the launch points for its attack against Simontorya.

The attack went in the following day, resulting in vicious urban combat that lasted until nightfall. By then, most of the town was secure. Meanwhile, I Cavalry Corps continued to make gains. The campaign so far had been an infantry matter for the most part, with armored troops struggling to even make contact with the enemy. The Cavalry Corps combined the usual capabilities of infantry with mounted mobility, proving surprisingly effective in the difficult conditions.

On March 12, the II SS Panzer Corps managed to gain control of Aba, which had been more or less cut off by the Corps’ successes the previous day. Soviet counterattacks began to develop in this sector but were initially driven off. The Corps moved to a defensive posture as pressure mounted. Despite requests for permission to pull back, the Corps was ordered to hold its ground. An attempt by the 23rd Panzer Division to cross the Sio canal and provide support proved unsuccessful, leaving II SS Panzer Corps in an increasingly dangerous position.

The I SS Panzer Corps had managed to establish a bridgehead across the Sio, which was repeatedly attacked on March 12 and 13. The Corps was targeted by most of the available Soviet air support while trying to beat off infantry and armored assaults. Despite the pressure, some elements of the corps were able to push out the bridgehead slightly.

However, the Soviet counteroffensive was getting underway. Concentration for their operation was largely completed by the 12th, and on the 14th the temperature rose. Drying ground facilitated more rapid movement and the deployment of larger armored forces.

The Soviet countermove was detected on March 13, but its extent was greatly underestimated. On the 14th, German commanders realized they were not seeing minor reinforcements but a major offensive getting underway. The objective was obvious—these forces intended to cut off 6th Panzer Army and annihilate it. Permission to withdraw was initially refused, forcing Dietrich to plead his case to Berlin.

Rather than admit the operation had failed, General Wohler, commanding Army Group South, proposed an alteration to the plan. The I and II SS Panzer Corps would attack eastward in concert, leaving the 23rd Panzer Division and I Cavalry Corps on the defensive in the current positions. These would be reinforced by Hungarian troops. This would require disengagement and regrouping, which was estimated to take four days. The plan was approved, but Berlin stipulated only three days to complete preparations.

Large-scale Soviet counterattacks developed on March 16, while the panzer formations were trying to disengage and regroup. Despite the misgivings of local commanders and recommendations from no lesser a personage than General Heinz Guderian, the panzer corps were ordered to continue preparations for their offensive rather than attacking the flank of the Soviet movements. Hitler refused to consider any changes to the plan, but eventually the commanders of Army Group South began to see it was not feasible. Orders arrived to prepare for an attack northward into the Soviet flank, and Wohler began requesting permission to use his force in a more practicable manner. This was eventually and reluctantly granted.

The 6th Army, which had been tasked with securing and supporting the operation, was unable to resist the Soviet attacks. As its supports were driven back, 6th Panzer Army risked encirclement and might have been annihilated but for the stubborn defense of the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, which held open a corridor to allow the force to escape, falling back to try to set up new defensive positions. By the 19th, all the territory gained had been retaken by the Soviets.

The 6th Panzer Army retired toward Vienna, maintaining good order despite heavy air attacks and pressure from Soviet ground forces. Troops of the panzer divisions noted that their Hungarian allies were less than enthusiastic about continuing the struggle and at times compromised the retreat by fleeing from their positions on the flanks. Other Hungarian units continued to fight well, however.

Despite the fact that the SS Panzer Corps had been given an impossible task, the Fuhrer was characteristically ungrateful. Sources differ on whether he issued an order for SS soldiers to remove their cuff titles as a sign of their disgrace or simply planned to issue one, but in the end the gesture was meaningless. Insignia had already been removed as part of the deception operations covering preparations for the offensive.

The remnants of 6th SS Panzer Army took part in the defense of Vienna in April 1945, and afterward, the force—or what remained of it—moved northwest and continued to resist as best it could. With the exception of some attached Hungarian forces, 6th Panzer Army surrendered to American troops at the end of the war.

In addition to the successful use of mounted troops, Operation Spring Awakening was unusual in that it was led by armored units that could make little use of their armor. The inability of the tank units to advance led to relatively low losses, though the panzergrenadiers suffered accordingly. In addition, the German Army maintained an effective recovery-and-repair capability and was able to return damaged or stuck tanks to operational condition as the offensive went on. As a result, the German armored forces were in relatively good condition at the end of the operation, though they suffered heavy losses thereafter.

The achievements of the infantry component are also notable, since these units had recently received replacements who did not have infantry training and experience. A mix of veteran panzergrenadiers and out-of-place sailors and Luftwaffe personnel bore the brunt of the operations and the difficult retreat afterward, though by that time conditions were such that the panzers were back in action.

Operation Spring Awakening can be viewed as another example of Nazi delusion, and the refusal of Hitler to accept defeat certainly played a part. However, there was a real strategic necessity to the counteroffensive that went beyond ego or denial. The willingness of the Nazi high command to commit its best remaining forces in Hungary rather than using them to stave off the fall of Berlin a little longer is indicative of just how critical this operation was seen to be.

Operation Spring Awakening was impossibly over-optimistic, but it offered just the slightest chance to avoid defeat. In that, it was the best option available at the time.

Martin J Dougherty is a freelance author who has published numerous books on history, conflict and mythology. He lives in north-east England, and is the current President of the British Federation for Historical Swordplay.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments