By Tom Wolforth

In July 1782, the island kingdom of Hawaii was fractured into three groups, beginning a power struggle that would last for the next 10 years. Similar in kind to the territorial disputes between England and France in the Hundred Years’ War, the sovereignty of the islands separated by the deep-blue waters of the Pacific Ocean had been disputed for generations between the rulers of Maui and Hawaii.

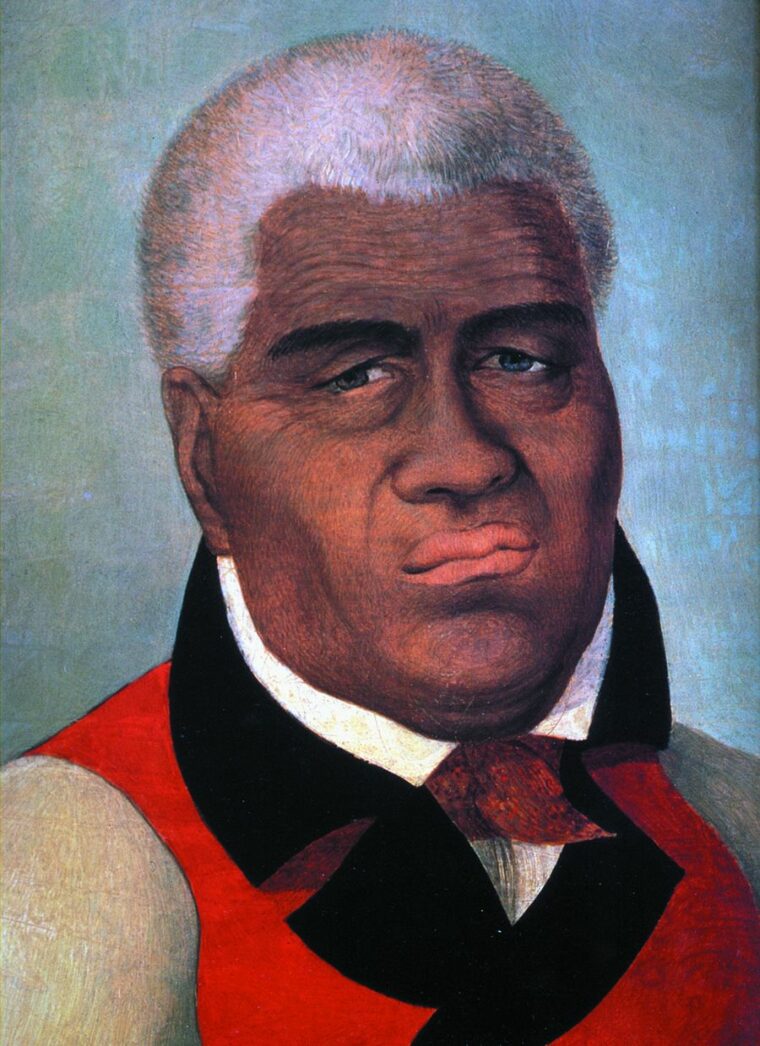

The death of the old Hawaiian monarch Kalanipou’u that year left a power vacuum on the large island. The rival claimants were warrior-princes Kamehameha and his cousins, Kiwala’o and Keoua. After a sharp clash at Mokuohai, Kiwala’o was killed and Kamehameha laid claim to the Hawaiian throne. A subsequent attempt by Kamehameha to conquer Maui was beaten back, and an uneasy peace settled over the islands for the next eight years.

Sowing the Seeds of War in the Hawaiian Islands

Increased trade with foreigners was partly responsible for the lack of warfare in the islands during this period, as rulers and commoners alike focused their attentions on understanding and exploiting the rapidly evolving economic situation. Foreign ships began to appear off Hawaiian shores more and more frequently, starting in 1786. By 1789, numerous whaling and trading ships were wintering in the islands. Many sailors jumped ship to become landlubbers in paradise, and some even served Hawaiian leaders as interpreters of foreign language and culture, and in managing the new and advanced alien weapons.

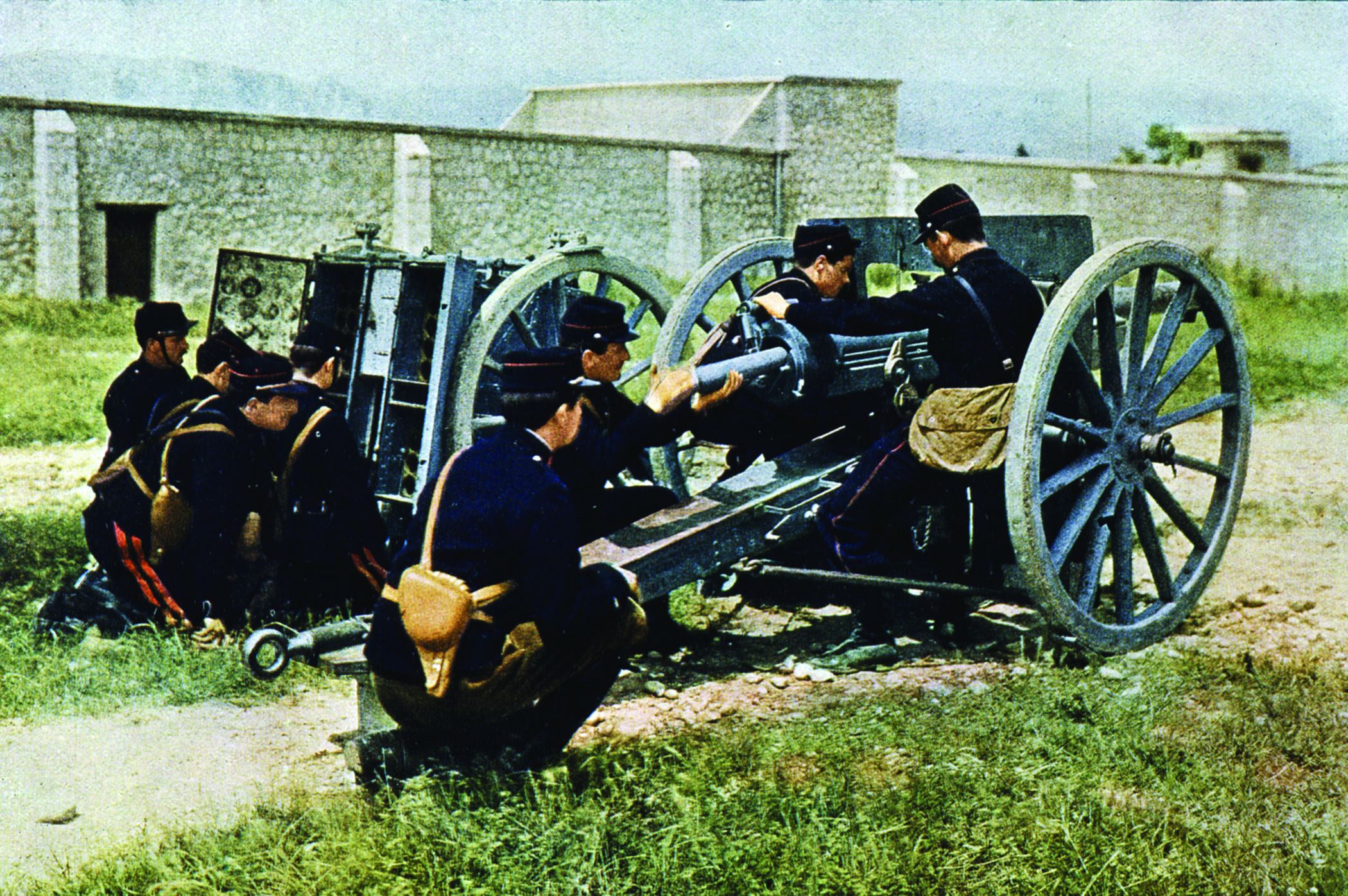

Although many peaceful interactions took place with sailors, traders, and visitors throughout the island chain, an unusual series of events culminated in placing a cannon and several guns in the hands of Kamehameha, and this in turn set in motion a new series of battles on the islands. In February 1790, Captain Simon Metcalf and his 18-year-old son Thomas were commanding two trading vessels, Eleanor and Fair American, off the shores of Honua’ula, Maui. After trading for small firearms and ammunition, a local chief returned at night with his followers to cut loose Eleanor’s little shore-going boat. The transgressors killed the sleeping watchman inside the boat and quickly took it apart for its iron.

Upon learning of the offense, Captain Metcalf managed to capture two prisoners and discover the details of the night’s killing. The captain was patient; several days later he invited the natives to trade aboard his ship. Many of those who took him up on his offer did not live to tell about it. Metcalf ordered cannons and small arms to open fire on the assemblage of canoes gathered around his ship. More than 100 native Hawaiians were killed, and another 200 were wounded. Metcalf weighed anchor and headed southeast to the island of Hawaii to rendezvous with Fair American, captained by his son.

Metcalf’s cruel ways of dealing with natives had already sown the seeds of his own destruction. Previously, the captain had whipped Kame’eiamoku, a notable headsman from Kona in west Hawaii. Kame’eiamoku had vowed to exact revenge on the next ship that strayed into his territory. True to his word, and unfortunately for the Metcalfs, that ship was Fair American. The ship’s complement consisted of the younger Metcalf and five sailors. They were no match for the angry Kame’eiamoku and his warriors, who stormed the ship, threw the crewmen overboard, and beat them to death with their paddle-oars. Only the ship’s mate, Isaac Davis, escaped death and was taken prisoner. The vessel was driven ashore, and her bounty of swords, guns, ammunition, and one cannon were be bestowed on the island’s ruler, Kamehameha.

The Conquests of Kamehameha

Several miles to the south, Eleanor anchored at Kealakekua Bay, scene of the fatal stabbing of Captain James Cook 11 years earlier. John Young, one of the several sailors who went ashore, lost his way and subsequently was captured by Kamehameha. Finding himself suddenly equipped with a cannon, plenty of ammunition and small arms, and two foreign sailors capable of effectively handling the artillery piece, Kamehameha was emboldened to return to Maui to settle old scores. This time the campaign was designed to take more than just the easternmost portion of the island—Kamehameha was ready to conquer all the Hawaiian islands. Looking to enhance his chances, he asked for assistance in the form of canoes, feathered capes, and warriors from an old rival in Hilo, Keawema’uhili. To the surprise of the third island chief, Keoua, Keawema’uhili decided to assist Kamehameha in his invasion of Maui.

Following an initial victory in east Maui, Kamehameha’s forces moved westward across the island by land and sea. The opposing forces met at the mouth of the Wailuku River in north central Maui, where one of the bloodiest battles of the campaign took place. Local noncombatants fled up the sides of the mountains on both sides of the river valley for safety, then watched in horror as the Hawaiian forces slowly pushed the Maui warriors back up the valley. At this point, Kamehameha unleashed his secret weapon—the cannon from Fair American. Under a ground-shaking bombardment, a majority of the Maui warriors were slain, their bodies clogging the Wailuku River and giving the battle the name Kepaniwai, or the damming of the waters.

Kamehameha pressed his advantage. In contrast to victors in the past, he did not bother to set up new headsmen on the conquered lands. Instead, he focused his attention on the next island to the west, heading to Kaunakakai on the island of Molokai. Victory there was achieved without violence after consultation with the ruling chieftains. Maui and Molokai were now under Kamehameha’s control. Taking Oahu would be a more difficult matter.

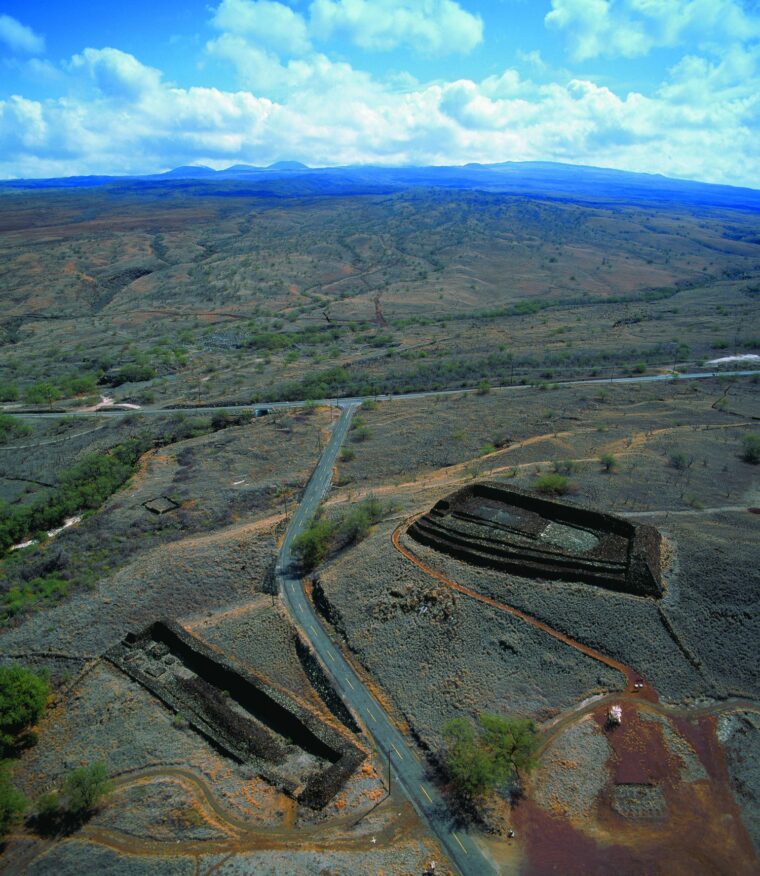

Kamehameha dispatched two messengers to Oahu. One exchanged messages with the shrewd but dying ruler Kahekili, who encouraged Kamehameha to wait until he had passed away before continuing his campaign of conquest. The other messenger sought out Kapoukahi, a respected prophet who instructed Kamehameha to build a large temple at Pu’ukohola, adjoining the old temple near Kawaihae. Once he had done that, Kamehameha would rule supreme over all Hawaii.

Kamehameha’s New Offensive

On the verge of moving farther westward, Kamehameha was forcibly reminded of unfinished business on his home island. Keoua had turned his anger on Keawema’uhili for helping Kamehameha and attacked the Hilo ruler at Alae, north of Hilo Bay. Keawema’uhili was killed, and Keoua extended his rule over two-thirds of the island. That was not enough, and he pressed his advantage while Kamehameha was away. Keoua’s forces marched westward into Kamehameha’s defenseless territory in Kohala, ravaging the countryside, destroying fields, fish ponds, temples, and the homes of the villagers.

By the time Kamehameha returned to Hawaii, Keoua had advanced as far west as Waimea. Kamehameha’s troops marched uphill and met Keoua’s force at Pa’auhau. Once again, the cannon from Fair American figured prominently in battle, serving Kamehameha’s forces well until it was captured by one of Keoua’s chiefs. The cannon was then used successfully against Kamehameha’s crew until its powder ran out. The fighting moved east to Koapapa the next day. On a wide-open plain, Kamehameha’s troops enjoyed greater firepower, but Keoua’s warriors were better at hand-to-hand combat. When Keoua ultimately retreated to Hilo, Kamehameha could not muster an effective pursuit. Although Kamehameha had succeeded in stopping Keoua from ravaging his lands, neither side had gained an outright victory, and each retired to his respective stronghold in the now-bisected island.

At this point, Kamehameha had gained ground in the islands to the west of Hawaii, but was losing ground on his home island. Keoua now controlled the warriors and resources that used to belong to Keawema’uhili, in addition to maintaining his original base at Ka’u. Kamehameha was unable to defeat the increasingly powerful Keoua, but he found help from an unexpected quarter. As Keoua marched his forces south from Hilo in November 1790 following the intense battle with Kamehameha in Kohala, the volcano Kilauea erupted for several days in a huge display of fire, sand, ash, and hot cinders. Many of Keoua’s army and supporters, perhaps 400 men, women, and children, died from the scalding-hot ash.

Kamehameha set out to capitalize on Keoua’s misfortune with a new offensive in 1791. Ke’eaumoku led an army against the Keoua forces stationed in Hilo. John Young and Isaac Davis were attached to the force. Ka’iana led another army into Keoua’s homelands on the southeastern part of the island. Ka’iana pressed his attack with a flotilla of canoes. Keoua maneuvered northward to Puna, where he dealt Ka’iana a severe blow, forcing him to retreat to Kona.

Western Cannons and Russian Dogs of War

Kamehameha had a tentative hold over Maui and Molokai, but Keoua was proving to be a formidable opponent. Kamehameha could not secure any of the westward islands while Keoua remained his enemy on Hilo, and the recent series of battles had made it clear that Kamehameha could not overcome his old enemy by force. He tried a different approach. Kamehameha focused all his resources on the building of a new temple at Pu’ukohola to abide by the directive of Kapoukahi. To expedite the building, Kamehameha personally joined in the construction work.

While Kamehameha’s attention was focused on building the temple and devising new ways to overcome Keoua, armies from the western islands were mounting an attack on his homeland only a few miles away on the other side of the Kohala Mountains. By this time, Oahu ruler Kahekili had joined forces with the Kauai ruler Ka’eokulanai, creating an alliance that held authority over all Hawaiian islands except the island of Hawaii. They decided to attack Kamehameha.

The combined forces left Oahu and stopped on Maui on their way. While on Maui, Kahekili agreed to transfer sovereignty of Maui to Ka’eo, the Kauai ruler. This unusual move upset the district chiefs of the Maui to the point of near mutiny. Somehow internal dissension was abated, and forces from Oahu and Kauai set out separately to rendezvous at different points along the Kohala coast of Hawaii.

The combined force from the western-island alliance was formidable. Famed warriors were supported by another foreigner, Mare Amara, who was able to work the cannons in their arsenal. One particularly large cannon was mounted on a canoe. Large fighting dogs obtained from Russians on Kauai were also brought along to inspire terror and inflict mortal wounds in the land battle they were preparing. Ka’eo’s forces were the first to arrive, and they devastated the valley of Waipio, the ancient capital of the island and home to rulers from past generations. Ka’eo went beyond the usual destruction of homesteads and agricultural fields, setting out to destroy the sacred temples of Paka’alana and Moa’ulahei. The invaders positioned their cannons at the mouth of the valley facing the ocean, preparing for Kamehameha’s inevitable advance.

Battle of the Red-Mouthed Gun

Kamehameha launched a fleet of double-hulled canoes from Kona as soon as he could. Many canoes were mounted with small cannons. He also sent a force by land. This group met and engaged the Kahekili forces north of Waipio valley. Ka’eo’s forces unwisely left their stronghold to join the battle. As the western alliance forces arrived in their canoes, they encountered Kamehameha’s fleet.

The two armies met in a battle at sea off of the cliffs of Waimanu. Sea battles had taken place in Hawaiian waters before, but this was the first one in which mounted cannons played a conspicuous part in the engagement, and the battle was dubbed Kepuwaha’ula’ula, or the Battle of the Red-Mouthed Gun. The cannons were successful in smashing the war canoes. Many lives, canoes, and cannons were lost on both sides, but the Hawaii islanders managed to best their opponents, sending the Maui and Kauai fleet retreating to Maui.

Although Keoua was not involved in the Battle of Kepuwaha’ula’ula, the results had a profound effect on his thoughts. Kamehameha invited Keoua to meet with him at the newly completed temple at Pu’ukohola. Surprisingly, Keoua agreed, traveling by canoe with a few of his advisers. As soon as Keoua set foot on land, he was fatally speared by some of Kamehameha’s followers. His body was then used as a sacrifice to consecrate the new temple and ensure Kamehameha’s rule over the entire island chain.

In early 1792, Kamehameha finally succeeded in taking complete control of the island of Hawaii. Three years later, after a long period of preparation, he defeated Kalanikupule in battle on the island of Oahu, literally driving his enemies over the rim of the inactive Puoaina volcano to their deaths 700 feet below. Following lengthy negotiations, Kamehameha was ceded control of both Oahu and Kauai, fulfilling Kapoukahi’s long-standing prophecy and unifying his hold on all of Hawaii.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments