By Berry Craig

First Lieutenant William Parks of the 101st Airborne Division left a snow-camouflaged helmet liner behind when the storied Screaming Eagles moved out following the American victory in the Battle of the Bulge in January 1945.

Seventy years later, the rare World War II relic is stateside with the paratrooper’s daughter, Patricia Parks Blaine, an education professor at West Kentucky Community and Technical College in Paducah. There is no doubt that the liner belonged to her dad, who died in 1993 at age 78. “PARKS WILLIAM” is scratched inside.

“When I saw the etched name, I said to myself, ‘Oh, my gosh, it’s his!’” Blaine remembered. “I recognized his writing.”

Blaine and the liner have been united thanks to retired Dallas attorney Joe Czajkowski, who got it last November from Charles Sibille, a Belgian friend. Sibille asked Czajkowski to try to return the relic to Parks or to somebody in the soldier’s family.

Czajkowski flew home to Texas determined to track down “PARKS WILLIAM” or a relative, a task that seemed daunting. He confessed he did not know where to start his search. “Do I contact the Department of Defense? Do I contact the Veterans’ Administration?” he thought.

Then it dawned on him: surf the net.

He sat down at his computer and Googled “William Parks” and “Battle of the Bulge.” Czajkowski immediately got the hit he was seeking, a link to a story in a Paducah publication about a college-sponsored World War II tour Blaine led in May 2014. “It took me maybe 15 seconds to find Pat,” he said with a grin.

At Bastogne, Blaine had found where her dad and his fellow soldiers were dug in on a hillside. The tour bus driver made a special trip past the site. Blaine had no idea that a few months later she would have the liner Lieutenant Parks may have worn under his steel pot at Bastogne.

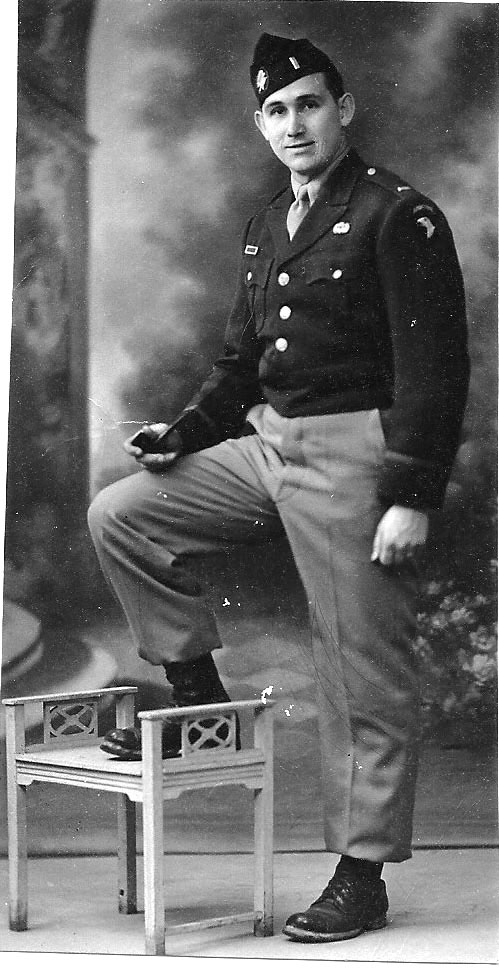

Meanwhile, her new friend Czajkowski also discovered a photo of Parks on the 101st Airborne Division Association’s website. He copied the image and e-mailed it to Blaine along with a note explaining that he had her father’s helmet liner. Blaine and her husband, Linford, were skeptical at first, but subsequent emails from Czajkowski included photos of the liner with Parks’ name clearly visible.

The lieutenant led the First Platoon in Easy Company of the 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment. The regiment was part of the approximately 12,000-man 101st Airborne Division contingent at the Battle of the Bulge, the largest and bloodiest battle the U.S. Army ever fought.

On July 1, 1941, the 502nd, dubbed the “Five-oh-deuce,” was activated as a parachute infantry battalion. In August 1942, the 502nd became the 101st Airborne’s first organic parachute infantry regiment, according to Army records.

The Battle of the Bulge began early on December 16, 1944, when approximately 200,000 German troops supported by tanks and other armored vehicles sprang a surprise attack out of the snowy Ardennes, the rough, hilly, and thickly timbered region where Belgium, Luxembourg, and France converge. Before the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions arrived as reinforcements, only about 83,000 Americans stood between the Nazis and victory.

Supported by artillery and advancing on a 60-mile front, German infantry and armor shoved a deep salient in the American lines. Because General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, had thrown so many troops into November offensives north and south of the Ardennes, his reserves consisted only of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions.

The 101st was resting and refitting at Camp Mourmelon, France, near Reims, when the men received orders to head to the front. Poor weather prevented a parachute drop; the paratroopers would travel in trucks. The “Screaming Eagles” departed, undaunted by cold rain and sleet. Speed was of the essence. After dark the trucks proceeded with their headlights on, risky business in a combat zone.

The division was bound for Bastogne a little over 100 miles to the east. “For the paratroopers packed in the trucks, Bastogne was just a rear area town housing a corps headquarters where they would probably get their orders,” wrote author Peter Elstob. “None could have guessed that it was a name that was about to become part of their division’s and their country’s history.”

Major General Maxwell D. Taylor, the 101st commander, would miss out on that history. He was stateside at a Washington staff conference. Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, the division’s artillery commander, found himself acting commander of the 101st Airborne Division as the troops raced toward Bastogne. McAuliffe could never have conceived in his wildest imaginings that someday his children’s children would visit this small town in southern Belgium to stand in the Grand Place, which would then be named “Place McAuliffe.”

The entire division was in Bastogne by the morning of December 19. Parks and the 502nd were deployed north and northwest of Bastogne. Soon, the Germans encircled the ancient market town that was the road and railroad hub of the Ardennes.

“It was kind of like a doughnut,” Parks remembered. “The Germans were the doughnut. We were the hole.”

Parks also said his men showed considerable Yankee ingenuity while fighting the Nazis in winter weather. Many of the enemy soldiers wore white suits for camouflage in the deep snow. The Americans had only GI olive drab uniforms. Parks said they devised their own camouflage by taking off their white longjohns and wearing them on the outside of their clothing.

Besides the paratroopers, another 10,800 or so GIs also hung on in Bastogne, including Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division. They were an assortment of rear area soldiers plus artillery, combat engineer, and tank destroyer outfits.

The enemy expected to quickly wipe out Bastogne’s beleaguered defenders or force them to give up. The Germans outnumbered the GIs about five to one, according to some sources. On the American side, heavy winter clothing, food, ammunition, medical supplies and just about everything else the GIs needed to hold the town were in short supply.

On December 22, the Germans demanded the Americans surrender or face “total annihilation.” McAuliffe famously replied, “Nuts.” Four days later, 4th Armored Division Sherman tanks from Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr.’s storied Third Army broke through the German lines to relieve Bastogne.

The weather also helped the Americans turn the tide. The U.S. Army Air Forces and British Royal Air Force had almost total air superiority over the Western Front, but dense fog and thick clouds over the Ardennes had kept the Allied air forces grounded. No sooner did the fog dissipate and the skies clear than lumbering C-47 transport planes showered Bastogne’s defenders with supplies while speedy P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers pounded the Germans with bombs, rockets, and .50-caliber machine-gun bullets.

Even so, bloody fighting continued in the Bulge into mid-January. But before the month was out, U.S. forces had erased German incursion and were preparing to strike at Germany itself.

On January 18, 1945, VIII Corps relieved the 101st in Bastogne. The division departed with a receipt from the corps command that acknowledged: “Received from the 101st Airborne Division, the town of Bastogne, Luxembourg Province, Belgium. Condition: Used but serviceable.”

The 101st Airborne’s courageous role in defending Bastogne earned the division a Distinguished Unit Citation (now a Presidential Unit Citation). It was said to be the first time in Army history that a whole division had received the award.

The successful defense of Bastogne was the key to German defeat in the Battle of the Bulge. The Screaming Eagles’ do-or-die stand earned them the nickname “The Battered Bastards of Bastogne.” Both sides were battered. About 75,000 Americans were killed, wounded, captured, or listed as missing. German casualties totaled as many as 100,000, according to official U.S. Army sources.

Parks’ helmet liner started on its almost 7,000-mile journey to Kentucky last November when Joe and his wife, Mary Pat, visited Charles and his wife, Anne, in Saint-Prex, Switzerland. The Sibilles also maintain a home in Brussels, the Belgian capital. “I was a lawyer for Exxon, and Charles was at one time a lawyer for our affiliate in Belgium,” Czajkowski explained.

“Regrettably I have very limited information to provide regarding the helmet’s history,” Sibille later explained in an email he asked Czajkowski to forward to Blaine. The olive-green liner, which fit inside a steel helmet, is in remarkably good condition. Most of the cloth webbing is intact, as is much of the white paint or whitewash that was daubed on it to provide better concealment in snow.

Sibille said that in the unusually cold and snowy winter of 1944-1945, his father was a young lawyer practicing in Ouffet, Belgium, about 50 miles northwest of Bastogne. “I remember my dad saying that American troops stayed in the village during and after the Battle of the Bulge. He also mentioned that he and my mother gave hospitality to American officers during that period.”

Sibille suggested that Parks may have been quartered in his parents’ home and perhaps forgot to take the liner when he and his men left. Sibille was glad the liner remained behind. He recalled that as children he, his brothers, and their friends enjoyed reenacting World War II battles using relics, including the helmet liner, and a steel German helmet.

“I remember vividly that we often quarreled and generally ended up tossing the dice to decide who was going to wear the American helmet because the game was always ending with the Americans crushing the Germans!” he said in the email.

Sibille remembered that after their parents died the children sold the family home. “While clearing up the attic I rediscovered the helmet and decided to take it to my house as a souvenir of our war games during my childhood.”

Sibille said he did not notice Parks’ name until shortly before he gave the liner to Czajkowski, whose 96-year-old father, retired Army Lt. Col. Anthony F. Czajkowski, is also a Battle of the Bulge veteran. Like Parks, who retired as a major, he earned a Bronze Star for bravery in battle during World War II.

In the email, Sibille said that when he spotted Parks’ name, he felt his “mission was to return the helmet to its former owner or his heir(s).” Sabille added, “Your being the son of a WW2 veteran who took part in the effort of freeing Belgium from the Nazis, I believe you are the ideal person to present the helmet to Lt. Parks’ daughter.

“Please tell Lt. Parks’ daughter how grateful the Sibille family is for what the United States did during World War II. Without the courage and sacrifices of these young men, we would still be part of Germany! Tell her also how delighted I am of this happy ending.”

The Czajkowskis presented the liner to Blaine and her husband, an Army veteran of the Vietnam War, in an impromptu January ceremony at the Paducah hotel where the Texans stayed during their trip from Dallas. The festivities included champagne, Belgian chocolates,

and World War II big band music playing from Czajkowski’s iPhone.

He had Blaine unveil the liner, which was inside a glass case he had built to protect the relic. The liner is at home with the Blaines, who live near Bandana, a small farming community near Paducah.

Lieutenant Parks, from Cristopher, Illinois, joined the Army around 1940 after serving in the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps. He also fought in the Korean War, his daughter said.

Parks came to Paducah in 1955 to help organize a local Army reserve unit. “It was his last assignment before he retired,” Blaine said.

Parks made combat jumps into Normandy on D-Day, June 6, 1944, and in Holland on September 17, 1944, during Operation Market-Garden. The college-sponsored trip included stops in Normandy.

“He told me that when he jumped at Normandy it looked like the world was coming to an end,” said Linford Parks, who is retired. “There were fires everywhere. The Germans were shooting at the planes. Antiaircraft shells were exploding everywhere.

“I asked him if he was reluctant to come out of the plane in Holland knowing what had happened in Normandy,” Parks concluded. “He said, ‘Hell no! The damn plane was on fire [from German antiaircraft guns].’ He said the pilots jumped, too, and they made infantrymen out of them.”

A first-time contributor to WWII History, Berry Craig resides in Mayfield, Kentucky.

Neat! Great story.