By Susan L. Brinson

George Sterling received a teletype message from the War Department just after 5:15 am on August 15, 1945. Less than 45 minutes later, Sterling, chief of the Federal Communications Commission’s Radio Intelligence Division (RID), handed a message to the RID’s teletype (TWX) operator to send to the monitoring station in San Leandro, California. “Send following message at once in clear.”

At virtually the same moment across the country in San Leandro, where it was 3:00 am, the teletype machine began typing. “Send following message at once in clear.” The monitoring officer’s jaw dropped as the message continued.

Not long thereafter, the Portland and Santa Ana monitoring stations received a different TWX message from the boss. “San Leandro will send important message to Japs. Listen … for any station that may acknowledge.”

Was World War II finally ending?

August 15, 1945, was an important date in United States history. Volumes have been written about the Japanese surrender to the Allied powers on that date and the formal ceremony held 18 days later aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay. But how did the United States and Japan make contact with each other to arrange the logistics of surrender? Virtually every known story focuses on the fits and starts of V-J Day, on the hesitations that occurred as the Japanese struggled to accept surrender, the roles that Sweden and Switzerland played as the diplomatic connections between the warring countries, and the worldwide celebrations that the end of World War II produced. The full story of how the Japanese and the Allies finally contacted each other has yet to be told. This is the story of the little-known Radio Intelligence Division of the Federal Communications Commission and how it played a key role in establishing initial contact between General Douglas MacArthur and the Japanese in order to formalize surrender and arrange the ceremony aboard the Missouri.

The RID’s War on Illegal Transmissions

The RID was formed on July 1, 1942, to monitor and locate enemy transmissions that threatened the United States, but it had been performing these duties for more than 30 years. Since a law was passed in 1910 to govern radio frequencies, the government had been monitoring the airwaves for illegal uses. During the 1930s, FCC engineers developed the technology and became proficient at tracking and capturing illegal transmissions, primarily among bootleggers and racetrack gamblers.

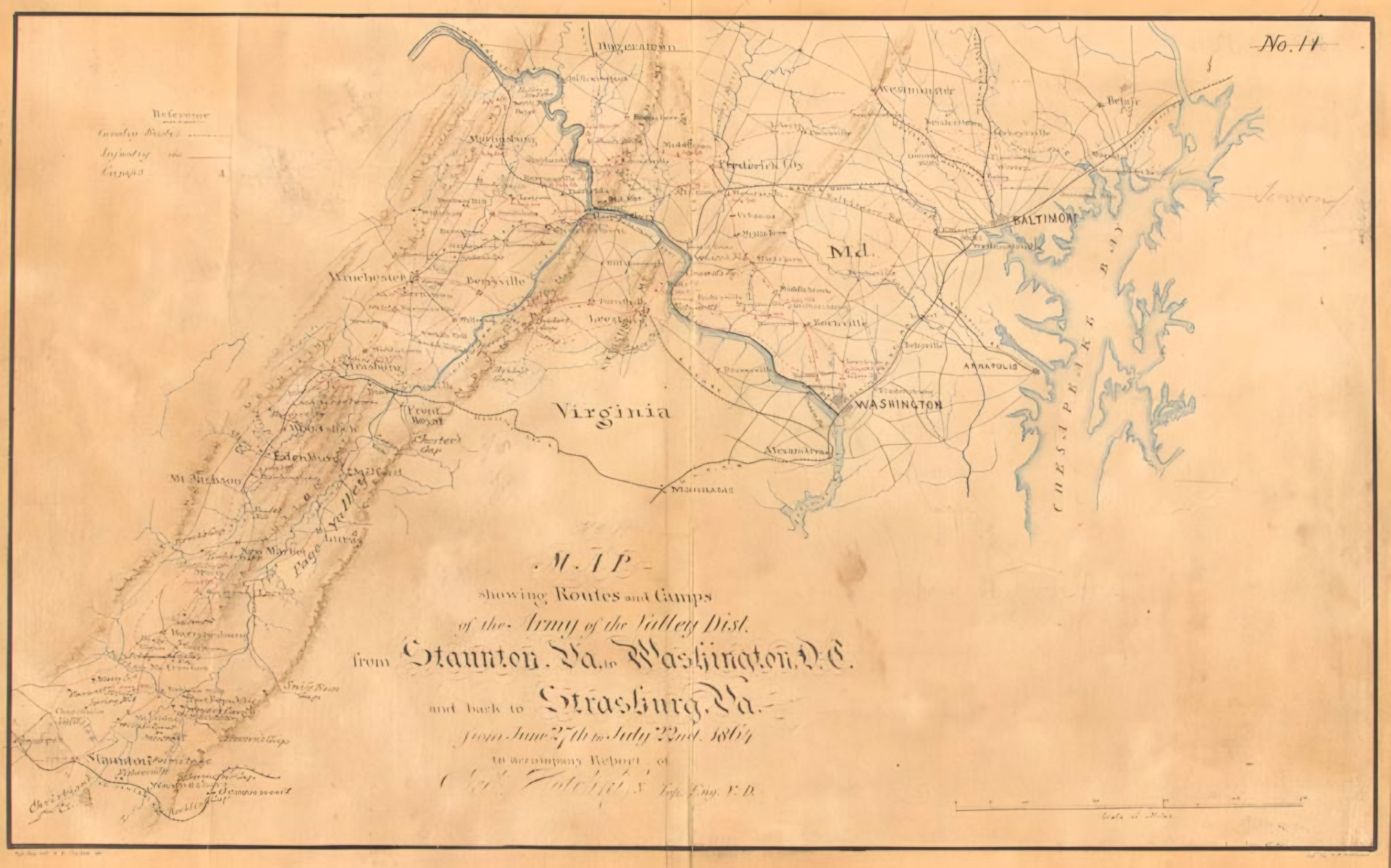

Protecting the United States from illegal transmissions required a safety net of monitoring stations throughout the country. Twelve primary and 90 secondary monitoring stations were established throughout the United States and its territories to accomplish that mission. After the start of World War II in 1939 and the United States’ increasing attention to domestic defense, its engineers were formed into the National Defense Office of the FCC and increasingly concentrated on transmissions coming from Germany, Italy, and their sympathetic allies. Sterling’s engineers proved their usefulness at locating clandestine messages when they intercepted and located a German spy operating from the German Embassy in Washington, D.C., two days after Pearl Harbor. By August 1945, RID officers had traveled all over South America looking for clandestine transmissions by German spies and on many occasions had helped the Army or Navy locate their downed pilots in the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans.

“Harnessing Radio to Help Fight the Global War”

When the U.S. entered the war in December 1941 after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, monitoring officers (MOs) at the western primary stations turned their attention to Japanese transmitters. Four stations in particular, located in Portland, Oregon; San Leandro and Santa Ana, California; and Honolulu, Hawaii, focused on finding and intercepting clandestine Japanese messages, absorbing Japanese Kana code, learning the frequencies over which the Japanese were most likely to transmit and the call signs they were likely to use, and otherwise focusing on understanding the “radio-operating characteristics of every type of radio-telegraph communications” that the Japanese used. Occasionally, the MOs would listen to and transcribe Japanese radio broadcasts, but these tasks were the exceptions to the rule; monitoring broadcasts officially was the responsibility of the FCC’s Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service (FBIS). Instead, the RID’s monitoring officers became highly skilled at discerning the difference between normal and unusual Japanese transmissions and particularly in intercepting and copying Japanese traffic in Kana code directly into Romaji (a system of writing Japanese using letters of the Latin alphabet).

Thus, when the RID was officially formed in June 1942, it was already well schooled in the practice of “maintaining a continual policing of the entire radio spectrum to insure against clandestine radio activity.” Information the RID stations collected was often turned over to several other entities, including the Army, Navy, War Department, State Department, FBI, War Communications Board, U.S. Weather Bureau, and U.S. Coast Guard. The RID’s massive data collection was written into several manuals “showing full particulars of all Japanese Naval and Military [networks]” as well as an additional “manual of authorized occupancy of all frequencies above 30,000 kcs.” The RID played an important role in protecting the home front and helping the United States fight World War II. Few other people knew Japanese transmissions better than the RID monitoring officers and their boss, George Sterling.

Although its specific missions were secret, the RID itself was public knowledge during the war. Newspapers and magazines often carried stories about the division’s accomplishments. Several articles were published in the Christian Science Monitor, the Radio News, and especially the New York Times that explained how the RID worked and described some of its exploits. Hollywood further promoted the division in 1944 when MGM produced a 20-minute film titled Patrolling the Ether, in which a RID investigator is murdered by a German spy caught transmitting from a cemetery. The German spy ring eventually is captured while transmitting from a moving automobile. While overly dramatic (RID men neither carried pistols routinely, nor were they murdered), it nonetheless accurately reported RID monitoring stations, technology, and methods, with the goal of “harnessing radio to help fight the global war.”

Japanese Surrender Anticipated

By mid-summer 1945, the western primary stations devoted increased attention to monitoring Japanese transmissions from all sources. Since V-E Day, and especially the bombing of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the western MOs hoped the Pacific War would end soon, too. They started paying particularly close attention to Japanese broadcasts from the Domei News Agency, which was controlled by Japan’s Ministry of Communications. Although monitoring such broadcasts actually was the responsibility of the FBIS, the RID maintained its own surveillance as well. Thus it was at 1:50 pm Eastern War Time (EWT) on August 10 when the Portland monitoring office reported to Sterling that Domei announced that the Japanese were “ready to accept the terms enumerated in the joint declaration which was issued at Potsdam.”

Any information about the anticipated end of World War II was top news, so celebrations broke out around the world when the story was reported to the public the next day, August 11. Almost immediately, announcements of Japan’s surrender were rescinded, and the world began a roller coaster ride of trying to determine whether the war was over or not. RID MOs continued to transmit so many transcribed Japanese broadcasts that Sterling, on the afternoon of August 13, admonished them to “refrain from transmitting” intercepts of broadcast messages, in part because it was the responsibility of the FBIS. More importantly, given the difficulties the United States encountered with making official contact with the Japanese and the growing worldwide tension regarding exactly when the surrender would occur, Sterling did not want his monitoring officers to contribute to the confusion.

Sterling, however, informed the western monitoring stations that he had “assigned a special task to [Portland] to keep [him] informed on Jap situation.” The Portland monitoring station took the lead on monitoring Japanese broadcasts. Sterling further told the other western monitoring stations that “any significant calls that appear to originate from Jap stations that appear to be unanswered should be reported [to him].”

Less than 12 hours after the Portland office received its assignment from Sterling, Monitoring Office Landsburg began sending updates to the boss. At 1:20 am EWT on August 14, Landsburg notified Sterling that Domei announced the “Japanese government started deliberations upon” the terms of surrender. Thirty minutes later, Landsburg telexed “FLASH!!! Learned Imperial message accepting Potsdam proclamation forthcoming.”

A Demanding Press

The western MOs waited for the expected announcement, but the airwaves remained silent on that score. Meanwhile, U.S. newspapers ran story after story about the anticipated Japanese surrender. The Washington Post, in particular, reported that the Japanese foreign minister visited the emperor on August 13, and cited the FCC as its source. Remembering Sterling’s admonition from just the day before, the MO at the San Leandro station assured Sterling that “no information [being reported in the news] is coming from here.”

By now the demand for current information was so high a San Francisco area reporter contacted the San Leandro station about doing an interview. Sterling initially gave permission but almost immediately rescinded it. The information the reporter sought was in the FBIS area of expertise. “Permission will be given after present crisis if then desired,” Sterling wrote to the San Leandro station. “You are instructed to refer all telephone calls to the supervisor of the western area which are received from representatives of government agencies, the press and public requesting information on radio communications pertaining to the current negotiations between the Allies and the Japanese.” Sterling was determined that the monitoring officers under his leadership would not be responsible for leaking information.

As tension around the world grew, Sterling tapped into the detailed information on which the RID’s outstanding reputation was built. He asked Landsburg which Japanese frequencies were likely to be active at 11 pm EWT. Landsburg responded using the J-codes assigned to Japanese stations: “JUP/JUD 13065/15880 kc … JZJ/JLT3 11800/15225 kc. These are the only frequencies we have knowledge of that will be active at [11 pm EWT]. However on especially important announcements Japs have been known to put all their [trans]mitters on the air.” Within 12 hours of this message, the western MOs would participate in establishing direct contact between General Douglas MacArthur and the Japanese.

A Message From MacArthur

In the early morning hours of August 15, 1945, in a sultry Washington, D.C., one of the FCC’s telex machines started receiving a message at 5:16 am. The telex was from the War Department in Washington. More specifically, it was from General Frank Stoner, head of the Army Communications Service in the Office of the Chief Signal Officer. Stoner instructed the FCC to have the “person of highest authority … have the following message transmitted in the clear in any or all means available if possible …. Request you have the following operational priority message transmitted by every practical means at once.”

In less than 45 minutes, at 6 am EWT, George Sterling relayed Stoner’s message to the San Leandro monitoring station. The message started with detailed instructions from Sterling: “Send following message at once in clear on three channels … signing your regular FCC call. At conclusion advise [the Honolulu monitoring station] to relay message using same procedure signing their regular call … At conclusion listen for reply to message from any Jap stations that may call you for verification or to transmit traffic. Make contact if possible to insure delivery of this message.”

The message that was received from Stoner, and which Sterling now directed the San Leandro monitoring station to transmit in plain English, started:

“Send in clear 15 August 1945

From Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

To the Japanese Emperor

To the Japanese Imperial Government

To the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters”

The message was from General Douglas MacArthur, who had been appointed supreme commander for the Allied powers only hours earlier. It took 20 minutes for the entire message to transmit to San Leandro. The MO whose jaw initially dropped as he read the message immediately acknowledged its receipt and followed up by asking for clarifications.

“Shall [Honolulu] use his 4 [letter] call also?” “Yes,” Sterling responded. “You are authorized to advise him re[garding] the transmission of this message in plain English.” A few minutes later, the MO further inquired, “See no call for [San Leandro] 4 letter [call sign] … Will you check this please?” Sterling responded, “You shall use the call ‘KFCA.’”

Signed MacArthur

The MO began transmitting MacArthur’s message immediately:

“From Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers

To the Japanese Emperor

To the Japanese Imperial Government

To the Japanese Imperial General Headquarters

I have been designated as the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers…. And empowered to arrange directly with the Japanese authorities for the cessation of hostilities at the earliest practicable date. It is desired that a radio station in the Tokyo area be officially designated for continuous use in handling radio communications between this headquarters and your headquarters. Your reply to this message should give call signs, frequencies, and station designation. It is desired that the radio communication with my headquarters in Manila be handled in English text. Pending designation by you of a station in the Tokyo area for use as above indicated, station JUM … on frequency 13705 … kilocycles will be used for this purpose and … Manila will reply on 15965 kilocycles. Upon receipt of this message acknowledge. /Signed/MacArthur”

Waiting For a Reply

Sterling waited for over three hours for any Japanese to respond. He heard nothing.

Sterling took action. At 8:41 am EWT he instructed the MO to send the message again: “Commencing at [9 am EWT] transmit for one hour at fifteen minute intervals McArthur’s [sic] message. Transmit at speed of twenty wpm good hand keying.” Only a minute later, Sterling sent an additional message to the Santa Ana and Portland monitoring stations, informing them that San Leandro would “send important message to Japs at [9 am EWT]. Listen at conclusion of message combing all bands for any station that may acknowledge or call [San Leandro]. Print any transmission intercepted for benefit of [San Leandro].”

The MO again sent the message, and again they waited.

Back in Washington, D.C., the teletype machine suddenly started transmitting a message from San Leandro. Had the Japanese responded?

No. It was the MO informing Sterling that “12 Naval District request identification on call ‘KFCA.’ Am I authorized to say if FCC?” Before Sterling could reply, the MO quickly followed up with “Skip it please. [He] hung up. Thanks anyway.”

A few minutes later, another message started coming from San Leandro. Had the Japanese answered the transmission?

Again, no. The MO was aggravated by the Honolulu monitoring officer, whom he instructed “to send that message only once. He is sending it again now and I am unable to make this broadcast at [9:30 EWT] due to [frequency use] of both of us.”

“Let it go [until] he’s done,” Sterling responded.

The MO allowed, “[He’ll] probably have better chance of Japs getting it from [Honolulu] but you said for him to only send it once. That’s the reason I mentioned it. Also fact that I can’t make this … schedule.”

A few minutes later, Sterling inquired, “any indication of reply to broadcast?”

“Not yet,” came the response. “There’s so many Japs on these channels [that I] can’t read any single one of them.”

And again a few minutes later came a message from the MO, “Haven’t heard any Japs using English yet. [They’re] all Kana [code].”

“Tokio [sic] Station Call Sign JNP Frequency 13740 … Language English”

Suddenly, on August 15 at 8:51 am EWT, the Santa Ana monitoring station transmitted “Jap just acknowledge message. Said [use] JNU3 13475 kc in few minutes for your official message. Adcock [direction finder] being secured until further notice.”

The RID had gotten through to the Japanese. Sterling relayed the frequency information to the War Department, after which the RID no longer transmitted on MacArthur’s behalf.

Over the next 36 hours, however, the RID continued to monitor the transmissions between MacArthur and the Japanese as they arranged for their emissaries to meet. At 10:35 am EWT on August 16, the Washington RID office received a message from the Portland station. The Japanese government had just sent a lengthy message to MacArthur in which the Japanese announced they were “in receipt of message of the United States government transmitted to us through the Swiss government and of a message from General MacArthur received by the Tokio [sic] radio graph office and desire to make the following communication [that] his majesty the Imperor [sic] issued an imperial order at 1600 oclock on August 16th to the entire armed forces to cease hostilities immediately.”

The Japanese further asked MacArthur to communicate with them on “Tokio [sic] station call sign JNP frequency 13740 … language English … in order to make sure that we have received without fail all communication sent by General MacArthur, we beg him to repeat” his message on the same frequency.

Ninety minutes later, at 11:37 am EWT, another message arrived from the Portland station containing additional information transmitted from the Japanese to MacArthur. This transmission included detailed information about the route that Japanese military leaders would take to arrive in Manchuria, China, and “the South.”

Less than an hour later, at 12:30 pm EWT, Landsburg at the Portland station transmitted the contents of a Domei broadcast to Sterling. “FLASH. The Imperial headquarters are endeavouring [sic] to transmit the Imperial order to every branch of the forces but before it took full effect a part of the Japanese air forces is reported to have made attack on the Allied bases and fleets in the south. While the Imperial headquarters are trying their best to prevent the reoccurrence of such incidents, the Allied fleets and convoys are again requested not to approach Japanese home waters until cease arrangements are made.”

The next morning, at 9:53 am EWT, the Portland office transmitted a long transcription of a Domei broadcast regarding Japan’s surrender. “As enunciated in Imperial [message, the] Potsdam declaration was accepted ‘because war situation has developed not necessarily in Japans advantage while general trends of world have all turned against her interests.’” The Domei asserted that the “Japanese people [should] not take an attitude [sic] that Japan would not have been defeated” if the military had used different strategies, if some countries had remained neutral, or the atomic bomb had not been dropped.

At 4:15 pm EWT on August 16, 1945, Sterling ordered the San Leandro and Portland monitoring officers to “discontinue copying coded material from Japan. Also cease copying point to point traffic between MacArthur and Japan and vice versa. Make certain that no one on your staff is making such copy.” Thirty-three minutes later, both stations acknowledged receipt of Sterling’s directive and bowed out of their role in the Japanese surrender.

Who Made First Contact With the Japanese?

As the excitement of V-J Day and the end of the war swelled, news media became interested in the FCC’s role in the surrender. The New York Times was one of the first to publish the story, on page one of its August 16 edition. “Two messages addressed to Tokyo asked first, for the establishment of radio communications between Tokyo and the Manila headquarters ….” They got the story right, but did not name the Radio Intelligence Division or the men who actually transmitted MacArthur’s message. Three days later the New York Times again reported that “on Wednesday [August 15] General MacArthur sent his first messages to Japan ordering establishment of radio facilities,” but, again, the report did not include the RID. The Portland Oregonian asked Landsburg at the Portland station for information about the Domei broadcast in which the Japanese accepted the Potsdam Declaration.

Landsburg asked Sterling’s permission to provide the information and reminded the chief that the “Domei [broadcast] in question was picked up by both RID and FBIS at same time.” The answer probably was not what Landsburg wanted to hear. “Since interception of Domei was an FBIS … show and RID was being used as a backstop … it is only ethical that [FBIS] personnel names be mentioned.” In any case, the Oregonian wanted to know who heard the first broadcast that the Japanese were surrendering, as opposed to who heard the first response to MacArthur’s message.

The request may have encouraged Sterling to pinpoint information, however. On August 17, he queried the West Coast monitoring stations asking who made first contact with the Japanese following the MacArthur message. Specifically, he wanted to know “what U.S. station either military or commercial made first contact?” The western monitoring stations combed their records of transmissions made during those tense hours. Ninety minutes later, the MO in San Leandro responded. “Have no available record of U.S. contact with Jap stations prior to” Santa Ana at 8:51 am EWT on the 15th. A day later, the Portland station confirmed the information. “No record of contact before” Santa Ana at 8:51 am EWT. As far as George Sterling and the monitoring officers were concerned, the first direct contact to establish the logistics of surrender between the Japanese and the United States occurred through the RID.

Dismantled and Forgotten

With the end of World War II, the RID was dismantled in 1946 and its responsibilities largely transferred to the newly formed CIA. George Sterling was appointed as an FCC commissioner in 1948 and served until 1954. Sterling published reminiscences about his RID experiences but never mentioned the MacArthur transmissions. He died in Baltimore in 1990 at the age of 96. Former members of the RID created a webpage at fccrid.org regarding the division in 2008, but it does not appear as if anything has been added since its creation. Nothing is known about Landsburg or any of the other monitoring officers who participated in establishing contact between MacArthur and the Japanese on August 15, 1945. Indeed, their story has never been fully told. Until now.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments