By Paul A. Thomsen

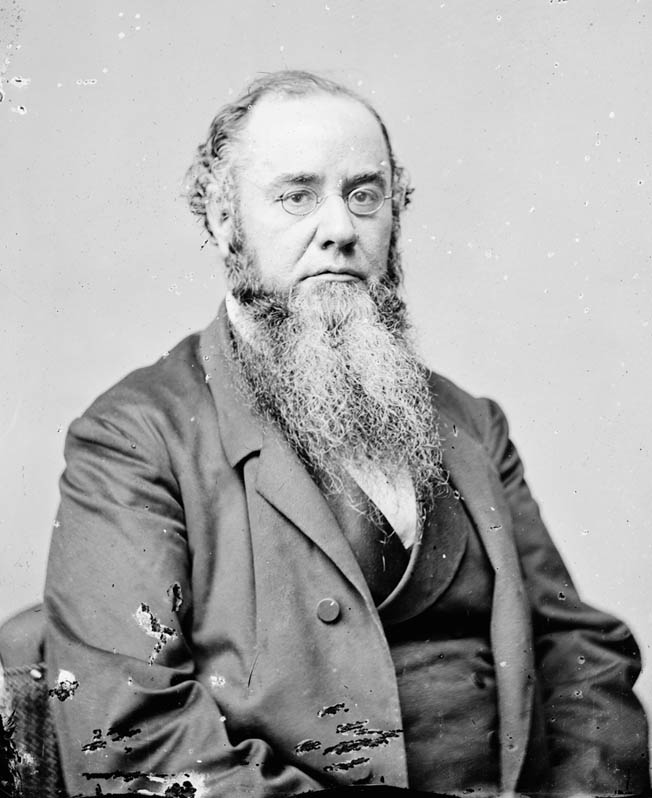

In the late hours of April 14, 1865, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton sat at a small table in the Petersen House across the street from Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C. Aided by a Union Army stenographer, Stanton labored to uncover the facts behind the shocking act that would soon claim the life of President Abraham Lincoln, who was lying unconscious in the adjacent rear bedroom.

With elements of both armies still in the field, Confederate agents still at large, and the border of the crumbling would-be Rebel nation only miles away, the secretary of war had assumed the responsibility for assessing the national security implications of the act and, where warranted, for bringing the full might of the United States military down upon those responsible.

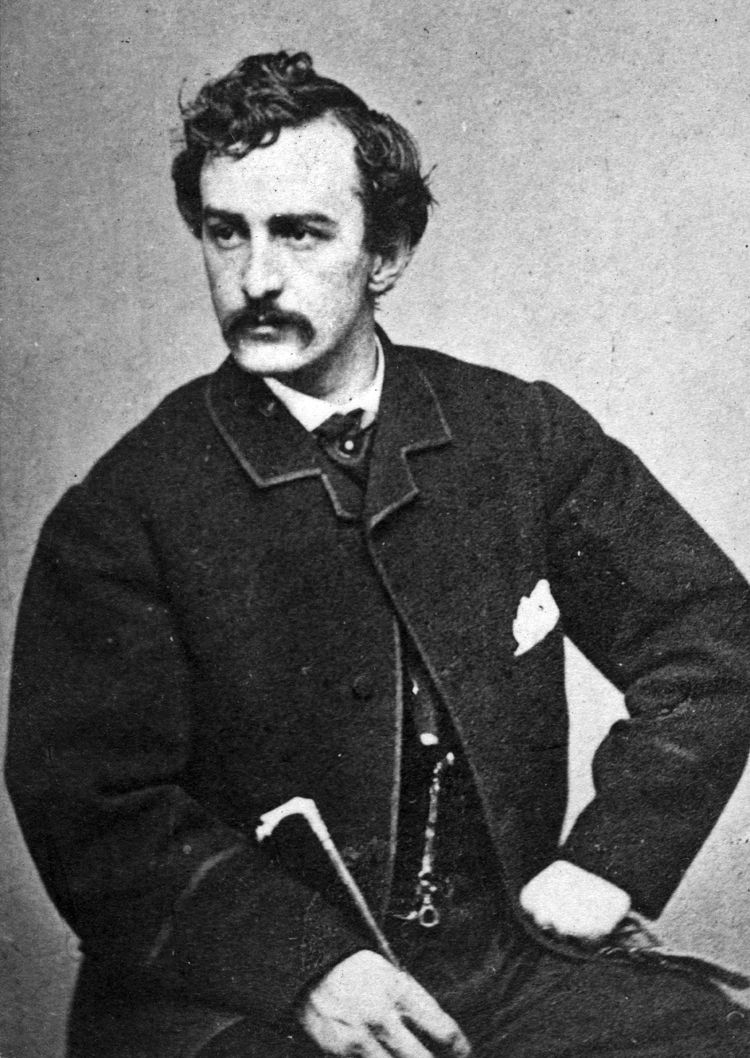

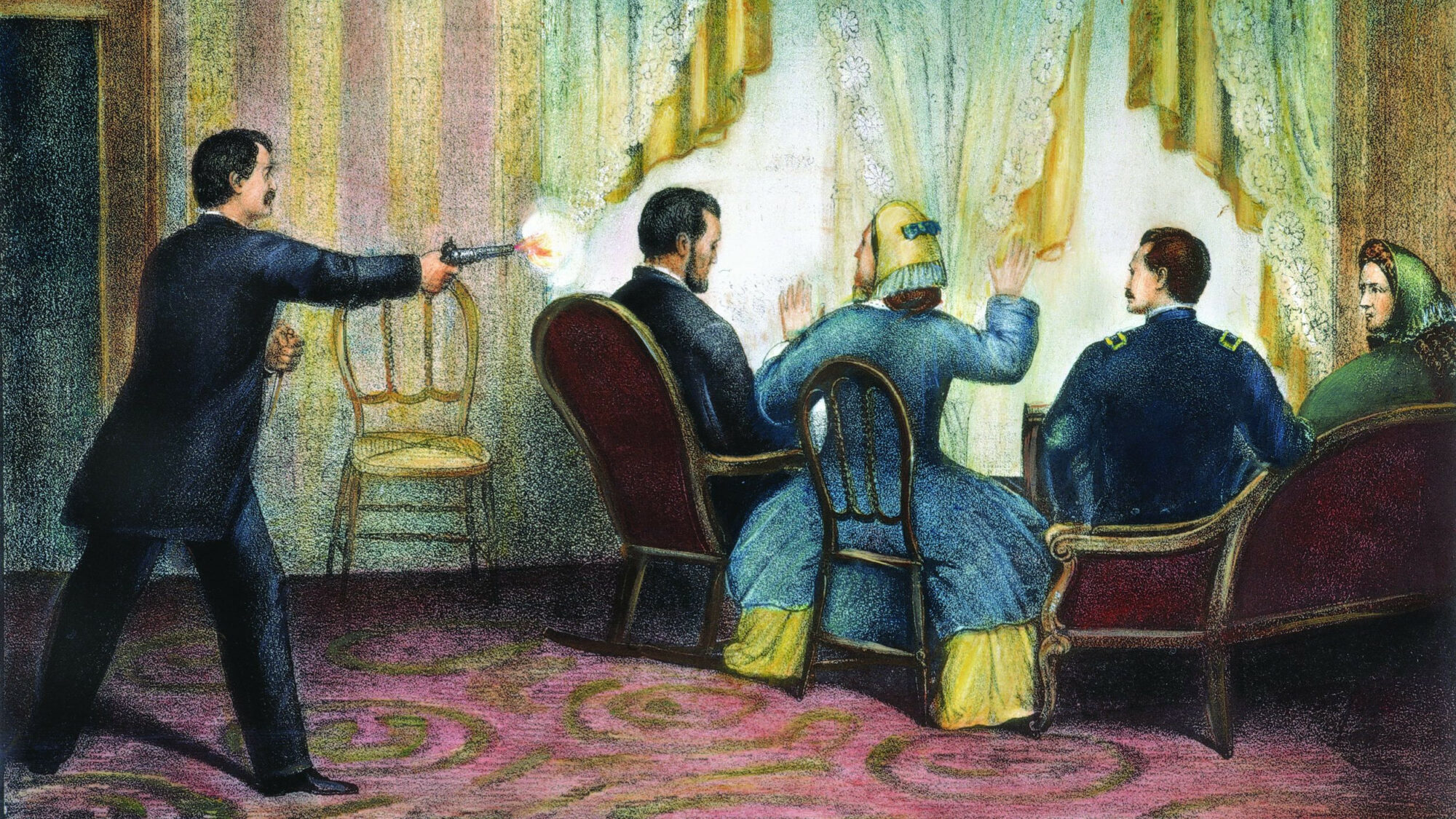

Minutes after arriving at the boarding house, Stanton’s ad hoc investigation had confirmed a number of alarming facts. Several witnesses attending the Ford’s Theater performance of Our American Cousin had seen Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth enter the presidential box, fire a metal ball into the back of the president’s head, and leap to the stage below, shouting: “Sic Semper Tyrannis! The South is avenged!” before disappearing into the night. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles and Senator Charles Sumner also reported that Secretary of State William Seward had narrowly survived a near-simultaneous attack at his residence across town. To Stanton and Lincoln’s other cabinet members and friends arriving by the minute, it seemed increasingly apparent that the disintegrating Confederacy had struck at the North through its leaders. Stanton, as the ranking, physically able cabinet member, was the man best qualified to ensure that the Confederates pay for their treachery.

John Stanton Becomes the Most Powerful Secretary of War

When Lincoln tapped Ohio-born Washington trial lawyer Stanton to become his secretary of war in January 1862, the former Buchanan administration attorney general rapidly proved himself to be a team player. Stanton became a valued gatekeeper of sensitive information and, eventually, the president’s personal crisis manager. Over time, Lincoln also came to rely on Stanton’s ability to walk a fine line between civil liberties and wartime necessity. In August 1862, for example, the secretary of war broadened the scope of Lincoln’s revocation of habeas corpus and military commissions to try civilians deemed dangerous, including an estimated 13,000 civilians arrested for “disloyal practices.” Stanton also took a personal interest in the president’s own security, stationing a military guard at the door of the Executive Mansion, detailing Union cavalry as ride-along bodyguards, and coordinating activities with the Washington police.

As the president’s breaths grew weaker by the moment, Stanton effectively became the most powerful unelected military leader in the history of the United States. Acting as the de facto commander in chief and unfettered by Lincoln’s temperance, Stanton methodically put into motion every military and extralegal measure at his disposal to stabilize the crisis. First, he ordered the city sealed from travel. Second, he superseded the authority of the Washington police commissioner and declared the area a military crime scene by asserting the president’s status as military commander. Third, he ordered the vice president placed under guard pending further developments. Next, he charged both police and military units to start gathering witnesses and evidence and arrest suspected associates of Booth for questioning. Finally, he disseminated news of the crisis to military posts throughout the country with orders to remain on full alert.

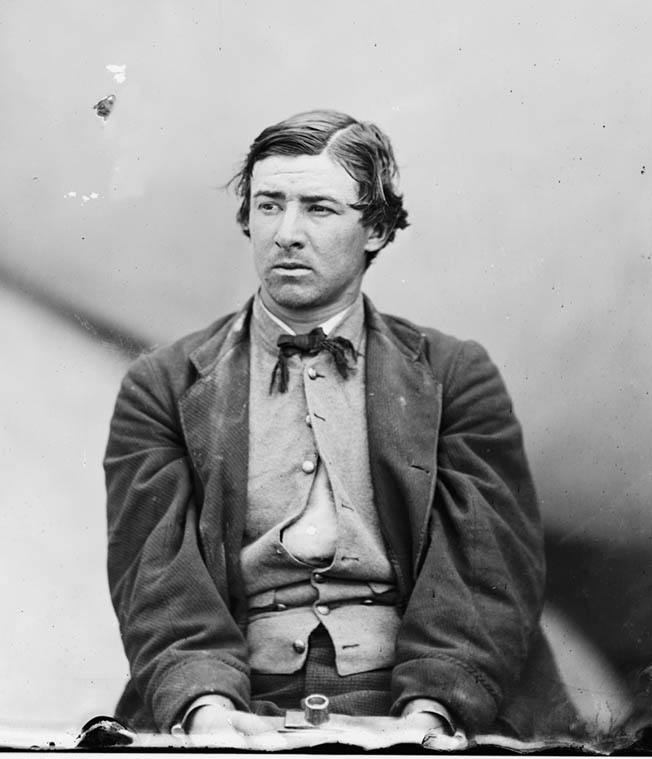

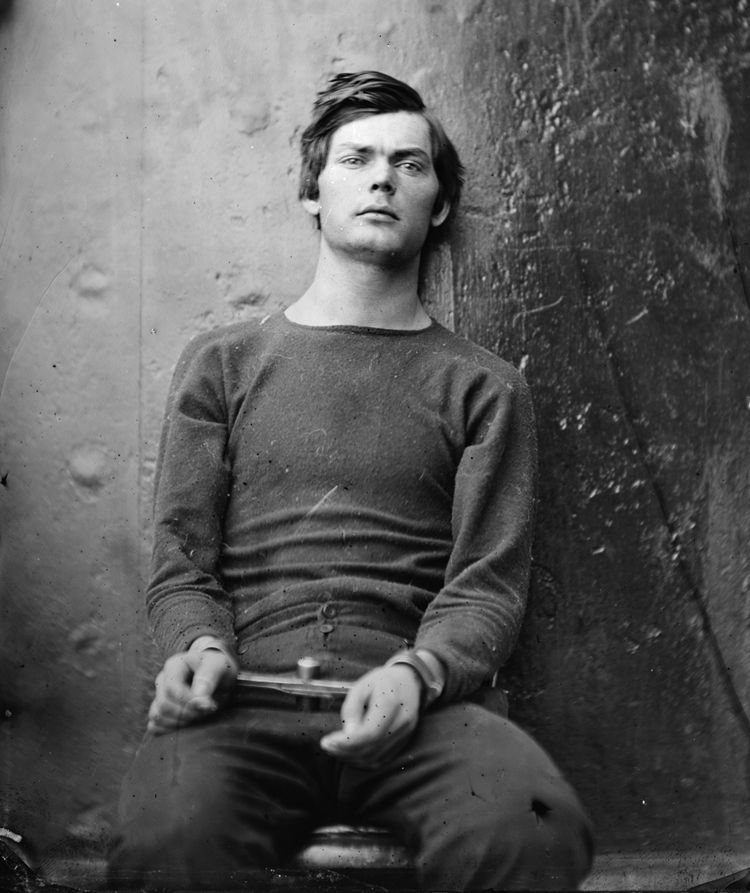

Shortly after Lincoln’s death at 7:22 am, Stanton began to focus on Washington’s small ring of Confederate sympathizers. On April 17, an army unit reported that it had found one of Booth’s associates, paroled Confederate soldier and would-be Seward assassin Lewis Payne (also known as Lewis Powell and Lewis Paine), entering the 541 H Street boarding house a few blocks away from Ford’s Theater that Booth had frequented. The arrest led to other Booth associates, including Mary Surratt, the mother of a known Confederate sympathizer and owner of the boarding house where Booth had met with his plotters.

On the same day, Confederate agents Michael O’Laughlin and Samuel Arnold were also arrested. Fearing military action, Arnold promptly confessed to taking part in a previous plot to capture—but not kill—the president. Within five days of the murder, the army had captured George Atzerodt for allegedly targeting Andrew Johnson for assassination and holding Booth’s Confederate ciphers. Next, Union soldiers seized a Maryland doctor who had treated the fleeing Booth, Dr. Samuel Mudd, and a stagehand who had held the actor’s horse at Ford’s Theater, Edman Spangler. Finally, the War Department distributed posters announcing Stanton’s authorization of a $50,000 reward for Booth and $25,000 for David Herold (sometimes spelled Harold) and for Mary Surratt’s suspiciously absent son, John. Stanton was closing in on his prey.

Over the next several days, Stanton’s deft handling of both the investigation and the winding down of the war bought the Executive Office time to grieve and contemplate its next move. President Andrew Johnson, the lone southern Unionist in Federal leadership and Lincoln’s successor, found no argument with either of Stanton’s crisis-managing roles. Johnson gave Stanton carte blanche to uncover the conspirators. Still, some cabinet members worried that Stanton was exceeding his authority. According to Gideon Welles, Stanton had become “mercurial—arbitrary and apprehensive, violent and fearful, rough and impulsive—yet possessed of ability and energy.” As the weeks passed, the secretary of war uncharacteristically hid his opinions, appearing “desirous of evading or avoiding the subject.”

Killing Booth

Stanton, in fact, was making a power grab. In mid-April, he provided the cabinet with specious documentation found floating on the Potomac River, which he presented as unimpeachable evidence indicating that Confederate President Jefferson Davis and other southern leaders had conspired to assassinate Lincoln, Johnson, and most of the cabinet. Stanton was already treating captured southern land as Union territory, granting military commanders the right to govern under martial law. He also spared no expense in pursuing the still-at-large Confederate president. As long as Davis remained free, Stanton believed unrepentant southerners might yet rekindle the war.

Andrew Johnson and most of the cabinet were swayed by Stanton’s persuasiveness and assented to the questionable use of the occupying Union Army as a military police force. Stanton’s army dragnet was validated on April 26, when the president’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth, and his accomplice, David Herold, were cornered in a Virginia barn by a Union cavalry patrol. The assassin refused to surrender and was shot and killed—against orders—by a Union Army sergeant and religious fanatic named Boston Corbett. The Army had gotten its man.

With Booth dead, the White House questioned what to do with his nine captured accomplices. Some in the cabinet wanted to give the prisoners a civilian trial. Stanton, however, challenged the notion by citing Lincoln administration precedents allowing for military trials of suspected antiloyalists. The co-conspirators had been discovered by military personnel, said Stanton, and were already quartered in nearby high-security military prisons. They should be tried and executed by military law.

Military Courts of the Civil War

Throughout the Civil War, military commissions were viewed as a legitimate means of administering justice where civilian courts might be considered partisan and time did not allow a lengthy exploration of facts and evidence. Under the Law of War, courts were “guided by the principles of justice, honor and humanity—virtues adorning a soldier even more than other men, for the very reason that he possesses the power of his arms against the unarmed.” The law also made keen distinctions between a spy, one who “secretly, in disguise or under false pretense, seeks information with the intention of communicating it to the enemy,” and a traitor, “a person in a place or district under martial law who, unauthorized by the military commander, gives information of any kind to the enemy, or holds intercourse with him.”

Military courts were highly organized affairs and an overt symbol of federal power. The courts were convened by a commanding officer of high rank and staffed by a panel of three to 10 military officers deployed at a military base or camp and conducted by military lawyers with optional civilian counsel. Prosecutors were forced to prove their case beyond a reasonable doubt. The defense was also required to provide a vigorous challenge to the prosecution on behalf of their clients, who were barred from speaking before the court in their own defense. At the conclusion of the argument phase, the judges were required to retire for deliberations and render a verdict based on a two-thirds majority. Following these guidelines, the 1864 Indianapolis Conspiracy trials had effectively processed several arrested individuals, convicting accused Copperheads (southern sympathizers) of planning to liberate Confederate prisoners in the North by force of arms. Given the fluid nature of the Booth conspiracy, Stanton’s military solution seemed a better alternative than letting the confessed conspirators and other possible collaborators evade justice in a questionable civilian trial.

Again, Stanton won the necessary support for his plans. On May 1, President Johnson signed a vaguely worded executive proclamation creating a military commission under Judge Advocate General Joseph Holt to try the “aiders and abettors and the persons implicated in the murder of the late President, Abraham Lincoln, and the attempted assassination of the Hon. William H. Seward, Secretary of State, and in an alleged conspiracy to assassinate other officers.” The nine prisoners were ordered moved to the Old Arsenal Penitentiary on the site of modern-day Fort McNair.

Attorney General James Speed was ordered to plan the prosecution and ensure that the military commission would continue to serve as judge, jury, and executioner. Stanton called on Holt to manage the daily running of the trial as the presiding judge of the commission. In 1862, Holt had written to Lincoln, describing the new secretary of war as “a friend true as steel, & a support, which no pressure from within or from without, will ever shake.” In 1863, Holt had taken part in Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside’s arrest of Peace Democrat Clement Vallandigham and the 1864 Indianapolis treason trials.

Trying the Booth Conspirators

On May 6, the Adjutant General’s Office released the names of the Booth conspirators’ judges: Maj. Gens. David Hunter, Lew Wallace, and August Kautz and Brig. Gens. Albion Howe, T. M. Harris and Robert Foster. Stanton appointed Congressman John Bingham and Colonel Henry Burnett to assist Holt as special judge advocates. With the assemblage of so many Lincoln friends and Union generals, the prisoners were virtually guaranteed a lynching party.

On May 9, the nine prisoners were led from their dank, stone-walled cells wearing shackles on their wrists and padded cotton hoods obscuring their faces. Almost blind and suffocating from the hoods, they were led upstairs to the newly erected third-floor courtroom of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary, where they were granted for the first time access to legal counsel. There were brief motions to block the removal of the prisoners’ hoods (which Stanton had directed the prisoners wear at all times) and to allow civilian representation at the trial. The judges awarded the prisoners minor conciliatory gestures, and the trial proceeded apace with the formal reading of charges.

Instead of presenting their case, the prosecutors first attacked the defense’s choice of counsel. During the war, they claimed, Mary Surratt’s lawyer, Reverdy Johnson, had not “recognized the moral obligation of an oath destined as a test of loyalty of the United States” and was therefore unqualified to represent the boarding house owner. Johnson, a Maryland lawyer, senator, and Zachary Taylor’s attorney general, had also represented Dred Scott in the infamous 1857 Supreme Court ruling. The claim against Johnson, born of his wartime criticisms of Stanton, was specious, and the Maryland lawyer countered the claim with a litany of causes he had served in the support of the federal government, the North, and his home state. The judges ruled in favor of Johnson as Surratt’s co-counsel.

The defense’s minor victories were short-lived. Over the next several hours, the prosecution implicated the prisoners by way of elaborate reports of supposed Confederate intelligence operations furnished by Stanton’s investigation. First, they presented the court with evidence discovered in the papers of Jefferson Davis after the fall of Richmond, indicating that Davis had used ciphered letters to conduct clandestine correspondence with field operatives. Second, the prosecutors provided the court with evidence relating to known Confederate Secret Service activities in Canada. The prosecutors cited testimony placing John Wilkes Booth and John Surratt in contact with the Canadian-based operations and produced Booth’s ciphers found in Atzerodt’s hotel room. Finally, the prosecution offered the coded letter purportedly found awash on the Potomac, tacitly linking Booth to the prisoners.

The Hangings

Over the following weeks, the prosecutors and defense counsel focused on the prisoners’ actions within the framework of a timeline of the April 15 assassination. They discussed Payne’s service with Confederate Colonel John Mosby’s raiders, Arnold’s and O’Laughlin’s ties to Booth’s original attempt to take Lincoln hostage, and Mudd’s past associations with Booth. The defense vigorously defended their clients, pointing out inconsistencies in eyewitness testimony and the dubious work of the War Department’s paid informants. Hoping to influence the judges, an anonymous supporter circulated a small pamphlet in Washington entitled The Trial of Mary Surratt, charging that the proceedings were a miscarriage of justice. The moves had little effect—both the defense counsel and the pamphlet writer were fighting a hopeless cause.

On June 30, the commission rendered its verdict. Herold, Atzerodt, Payne, and Surratt were sentenced to hang for their direct complicity in Booth’s assassination plot. Arnold, Mudd, and O’Laughlin were sentenced to life imprisonment at a military fortress in the Dry Tortugas for their presumed knowledge of the conspiracy, and Spangler was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment for unwittingly holding the assassin’s horse. A few military judges drafted a petition to the president, asking that Surratt’s life be spared on gender grounds, but the note somehow never reached the president. On July 5, Andrew Johnson approved the original sentences as submitted.

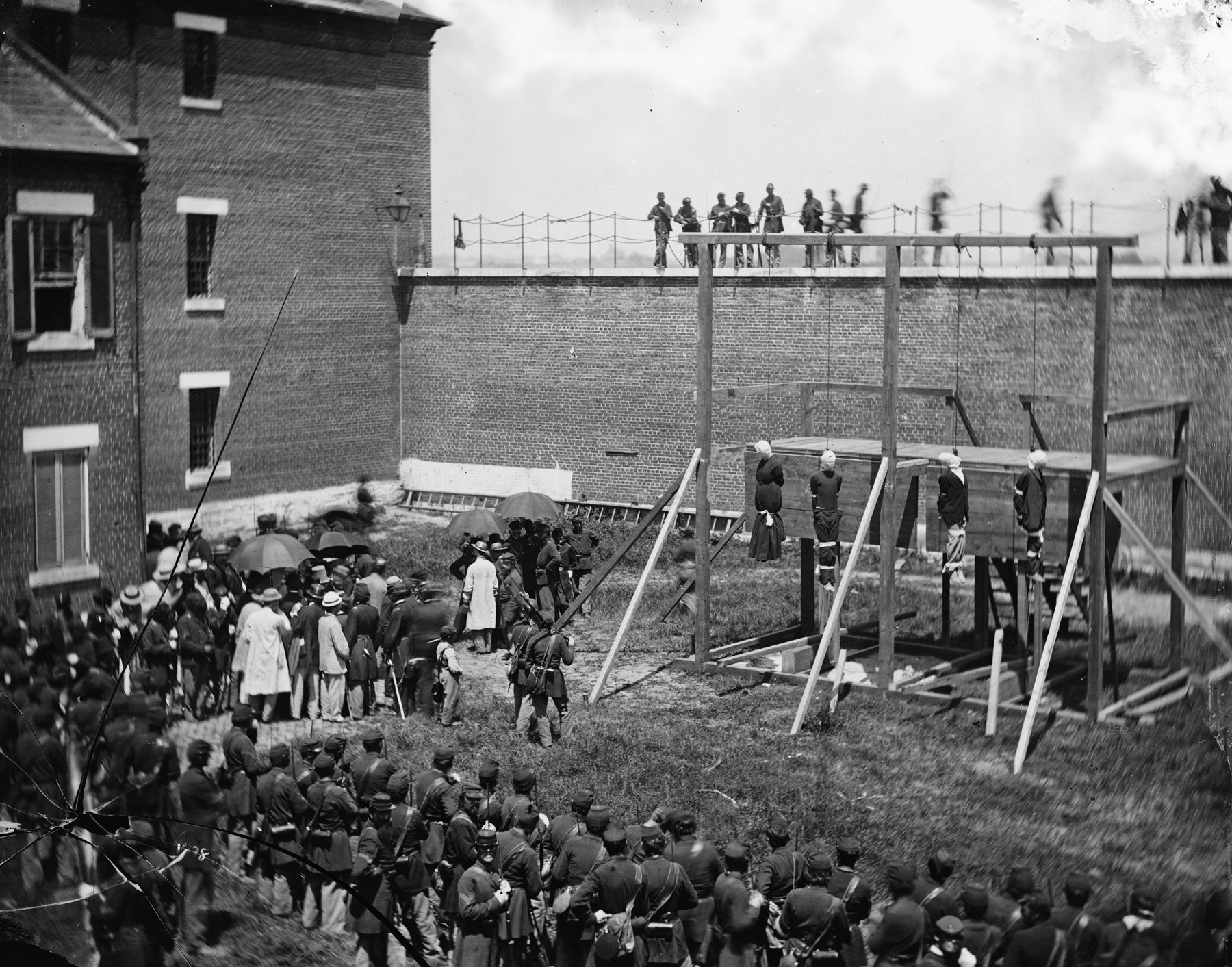

On the afternoon of July 7, Edwin Stanton had his vengeance. The four condemned prisoners were marched into the yard of the Old Arsenal Penitentiary before a waiting crowd of bitter and raucous onlookers. They mounted a newly erected wooden army scaffold and, amid shouted taunts and jeers, were hanged by the neck until dead and then deposited in shallow graves in the shadow of the penitentiary wall.

Johnson vs Stanton: The Political War in Washington

Although a wider conspiracy was never proven, Stanton continued to press for punishment of the South as a whole during Reconstruction. Bowing to political pressure, he was not able to prosecute Jefferson Davis by military commission, and Davis was freed after two years in virtually solitary confinement. Much to Stanton’s chagrin, John Surratt was captured in the Vatican and returned to the United States to be tried in civilian court for his alleged role in the assassination. He was acquitted on almost the same evidence Stanton had provided against Surratt’s mother. It was a stinging rebuke to Stanton, Holt, and their associates.

Eventually Johnson attempted to put an end to Stanton’s power grab. In August 1867, the president tried to fire the Radical Republicans’ favorite cabinet officer. In response, Congress declared a political war against Johnson, launching the first impeachment trial of an American president. Failing in that highly questionable effort, Congress enacted the Tenure of Office Act, which effectively permitted Stanton to retain his position. Finally, in 1878, a year after the Union Army had withdrawn its military occupation of the South, a politically different Congress passed the Posse Comitatus Act, which prohibited the American military from domestic law enforcement or involvement in national security matters. By then, both Johnson and Stanton were long since dead.

Some people are great military leaders, a few are great government leaders. Almost none are both with the possible modern exceptions of Churchill and Eisenhower.

The United States Constitution is a very hard thing to keep and adhere to especially in times of national division, crisis, and passion. It is every American citizen’s duty to see to it that it is faithfully followed, unless admended in the proper way. If you don’t work for that and vote accordingly, that’s on you! One of the founders said they had given us a republic, if we could keep it. It’s the responsibility of each generation to secure it for their children!