By Dan Dougherty

BACKSTORY: Dan Dougherty graduated from Central High School in Austin, Minnesota in June 1943 and was immediately activated from the Army Reserve. After four months of infantry basic training at Fort McClellan and five months in the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) at St. Louis University, he was assigned to the 44th Infantry Division.

When the ASTP folded in March 1944, he completed precombat training at Camp Phillips near Salina, Kansas, and sailed for Cherbourg from the Boston POE on September 5, 1944. The 44th started fighting in the Seventh Army sector near Luneville, France, on October 18, 1944, with Pfc. Dougherty serving as BAR gunner in the 2nd Platoon, K Company, 324th Regiment.

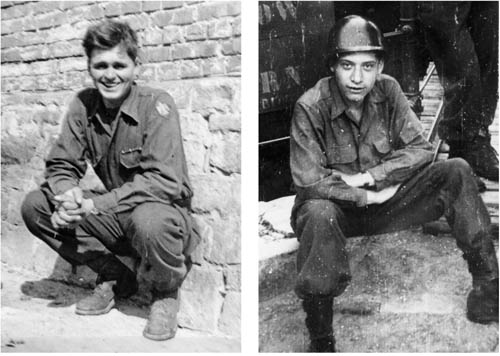

When six companies of the 157th Regiment of the 45th Infantry Division were captured in Alsace (Operation Nordwind) in January 1945, 180 sergeants from other Seventh Army divisions were immediately transferred to the 157th to help reform those units; Dan and Leonard Parker were two of the 12 sergeants from the 44th Division who joined C Company at that time. On March 18, 1945, Dan was wounded during fighting on the Siegfried Line; he returned to the unit from the hospital on April 2 and thus missed crossing the Rhine along with much of the Aschaffenburg battle, but still saw plenty of action, and saw the Dachau concentration camp first-hand. This is his story.

We were with the tanks when C Company hit the Siegfried Line on the morning of March 18, 1945. They had to stop at the huge tank ditch but kept blasting away at any bunkers they could see. We climbed in and out of the ditch, crawled under barbed wire, walked through the cement dragon’s teeth (perhaps this before the ditch, I don’t remember), and then proceeded toward the bunkers.

We would put a hand grenade through the gun slits of the bunkers and keep going. Every now and then, we entered a bunker from the back door. We did use the German hand grenades we found, but I never saw a live German soldier. We made very good progress for maybe 45-60 minutes, and then came the mother of all artillery barrages. We were in heavy woods, and there were many, many tree bursts. The morning reports for March 18-20 list 35 casualties for C Company, including five KIA.

I was walking when I felt a light thud in my left foot. This was probably about the time the barrage ended. There was no pain or blood, but I sat down in the middle of the Siegfried Line and took off my shoe and found a slit in the tread near the ball of my foot. I was wearing two pairs of socks and there was about a ¾-inch slit through each.

It’s difficult to see the bottom of your foot, but I could make out a small wound that looked black and blue with no pain or bleeding. I don’t remember, but I probably took my sulfa pills. When you get shrapnel in the ball of your foot while walking, I always assumed it had to come from a very low-grade mortar that had landed nearby. I can’t even find the scar today.

Before heading back, I tried to assist a GI who was down and moaning. I asked him if he’d taken his sulfa pills, and he said no. I was about to help him do that when I had the presence of mind to ask him where he was hit. It turned out to be a nasty wound in the middle of his back so we skipped the pills. I don’t remember who he was and would be surprised if he survived.

While walking back to the battalion aid station, I hitched a ride in a jeep. I was in the front next to the driver, and a GI in the back seat was crying very hard with no apparent wound. It turned out to be Private Floyd Bonner from another platoon who had become very distraught when his identical twin brother Lloyd was severely wounded.

Floyd probably returned to the unit that day or the next because there’s no mention in the morning report of his absence. Floyd and Lloyd had joined C Company in the fall of 1944 and missed being captured at Reipertswiller, France, because both were out with trench foot. (Floyd was killed at Aschaffenburg on March 29, 1945, and is buried at the U.S. cemetery at St. Avold, France. Lloyd died in 1988.)

My experience in the field hospital was hilarious. When the nurse came to administer the anesthetic, I told her I really wanted the shrapnel as a souvenir. “Sure, soldier,” she replied. No shrapnel was saved. When they gave me the Purple Heart, I wrapped my two socks with the slits around it and went to the Red Cross tent to mail it home. “I want these socks as a souvenir.” “Sure, soldier.” But they were never sent.

To give you an idea of how seriously I was wounded, I played ping-pong two days after having surgery on my left foot. Someone with authority must have seen me, because the next day I was heading back to the replacement depot. Of all the C Company casualties in the Siegfried Line, I was the first one back to the unit. We’d been at full strength on March 18. On April 2, I brought the second platoon number up to 13 (a platoon was normally about 40 men). Ben Ewing was the only sergeant not hit, and he was now platoon sergeant.

Snipers in Nuremberg

On April 15, 1945, in the closing days of World War II in Europe, Seventh Army troops (the 3rd, 42nd, and 45th Infantry Divisions) had surrounded Nuremberg, and if anyone but Hitler had been in charge, the city would have been surrendered. It was defended, and so the first day, we (C Company, 157th Regiment, 45th Division) sat on the bluffs and watched planes of the Army Air Forces repeatedly dive-bomb the city with no opposition.

Four days later, the three divisions converged in the center of Nuremberg, and that night C Company hiked back to the suburbs to find a standing building in which we could sleep.

A big problem for infantry troops in Nuremberg was snipers, and one victim was Corporal Edwin G. Wilkin of our platoon, who was killed in action. He posthumously received the Medal of Honor for his actions earlier in the battle of the Siegfried Line.

In 1948, when Wilkin’s remains were returned to his home town of Longmeadow, Massachusetts, his mother called to invite me to attend the Memorial Day service, but I was in the middle of college finals in Minnesota and couldn’t go. Army Chief of Staff General Omar N. Bradley spoke, and John Scherer and James Crane represented our platoon as honorary pallbearers.

The 45th (“Thunderbird”) and 42nd (“Rainbow”) Infantry Divisions left Nuremberg on April 22 and were heading for Munich with the goal of getting there as soon as possible so as to deny the Germans time to organize a defense as they had at Nuremberg. The German military effort was collapsing, and we often rode tanks or tank destroyers just to keep up.

Privates Virgil S. Kay and Joseph Marshall were two of 12 replacements who joined C Company on April 20, and they were both wounded on the 25th; Kay died in the hospital on May 6. He had served just five days in C Company and was our last fatality of the war.

DUKWs Crossing the Danube

We arrived at the Danube on the morning of the 26th. The bridges in our area were blown, and while we waited for “ducks” (DUKW was the Army’s designation) to take us across, I wrote to my parents, “Well, here I am humming the Blue Danube Waltz while looking at the Danube River. Not supposed to tell you where I am, but our lieutenant never reads the mail so I’m not limited much.” (One duty of platoon leaders was to censor the outgoing mail, but by that time it was obvious that the war was ending and our lieutenant had me, the platoon guide, signing off for him on the envelopes.)

While crossing the river that morning, the engine conked out in the duck in which my group was riding, and we quite literally became a sitting duck as we floated deeper into possibly hostile territory on the swiftly flowing Danube.

The engineer eventually restarted the engine and got us across, but we had traveled quite a ways downstream and felt lucky not to have been shot at. There were about seven or eight of us GIs, and we didn’t locate the 45th Division until the afternoon of the next day. I never felt good about the fact that, hungry and without food, we stole K-rations from another division that day.

“I Company’s Gone Berserk!”: Visiting the Dachau Concentration Camp

By April 28, we were nearing Munich and that night we slept in some woods, which was unusual because by that time we were almost insisting on sleeping in homes. When we assembled in the morning to get our rations, our commanding officer, 1st Lt. Bert V. Edmunds, said, “Gather around, guys. I have to give you special orders.”

Nothing like that had ever happened before, and I remember his telling us the division was in the vicinity of a concentration camp and it was important that witnesses be kept alive.

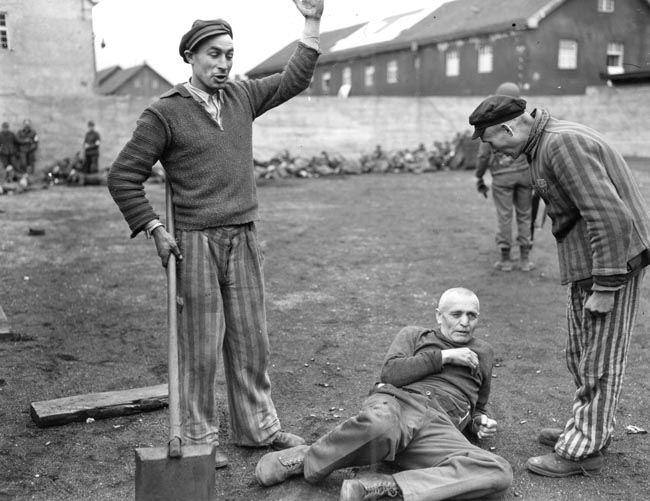

This meant nothing to us. We didn’t know what a concentration camp was, and besides, C Company was in reserve that day. We had an easy stop-and-go morning but about 1:00, our company runner came to our platoon. I was standing by him when he told us, “We’re going into a concentration camp to relieve I Company because I Company’s gone berserk!”

[Editor’s note: I Company, 157th, had been the first unit to stumble onto the Dachau concentration camp, 10 miles northwest of Munich, that day, and had been shocked by the scenes of death all around. Unprepared for such an encounter, they rounded up a group of SS soldiers who were guarding the camp after the regular guards fled and lined them up in the camp’s coal yard. A trigger-happy GI opened fire on the SS men, followed by volleys of fire from some of the other I Company troops. Within seconds, 17 SS men were dead and others wounded.]

So, we had to hike over to the 3rd Battalion sector. My recollection is that we arrived at the Dachau concentration camp between 3 and 4 pm, but others remember it as earlier. We didn’t know the name of the place, and even if we’d been told, it would not have meant anything. None of us had ever heard of Dachau.

On Sunday, April 29, 1945, we approached the Dachau concentration camp on a road from the southwest. Up ahead we saw boxcars and gondola cars on the railroad track that paralleled the road on our left. When we reached the cars, the doors were open, and we made the horrifying discovery that they contained the most emaciated corpses imaginable. The bodies were nothing but skin and bones, still mostly in the remnants of their striped uniforms. There’s no way to prepare for such an experience. We would stare and then walk to the next car and stare some more.

The eyes on some of the bodies were open and they stared right back at us. No one had anything profound to say, just an occasional “My God!” Turned out there were 39 cars with 2,310 corpses. That’s an average of almost 60 bodies per car.

At the time, of course, we knew nothing about the origins of the train or what had happened, but we now know the whole story and that train belonged as much to the history of Buchenwald as Dachau.

The Buchenwald-Dachau Death Train

In brief, the train had left Buchenwald near Weimar on April 7 with 4,500 prisoners jammed into 55 cars headed for Flossenbürg (a large slave-labor camp where noted pastor and theologian Dietrich Bonhöffer and the head of German military intelligence, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, were executed on April 9), but during the trip the train was rerouted to Dachau where, after a three-week journey, it arrived on the 28th, the day before we arrived. It is now referred to as the Buchenwald-Dachau Death Train. The Dachau commandant’s journal for April 28 listed 816 survivors. They must have crawled out of the boxcars. (Get more first-hand accounts of the Second World War by subscribing to WWII History magazine.)

Once inside the camp, our platoon leader, James Penny, said, “Okay, guys, fan out and look for guards.” Some went right, some straight ahead, and I went to the left with Jim Killingbeck and others.

[Editor’s note: Shortly after I Company arrived at the railroad gate where the train and 2,310 corpses were, advance elements of the 42nd Division reached the camp’s main gate—neither organization knew the other was there—and took the surrender of the camp from an SS officer who had been left in charge.]

In the course of rounding up several hundred guards, some of the 45th and 42nd Division troops—officers and GIs alike—had a breakdown in discipline that day in different unrelated incidents, but there was a lot of provocation. I’ve never seen evidence that more than about 30 guards were killed without benefit of a trial.

Shooting of the Dachau Guards

There was an investigation of the killing of the guards but no charges were ever filed. There’s a strong presumption that the report was quashed by General George Patton when he commanded the Army of Occupation of Bavaria after the war. At a different time in a different war, there might have been a prosecution but at the conclusion of World War II in Europe, during which the evils of the Nazi tyranny had been laid bare, there was no interest in pursuing the matter.

We soon came to another amazing sight—about a dozen reporters in civilian clothes milling around SS corpses in what turned out to be the camp’s coal yard. In anticipation of the liberation, the Army had assembled this media group behind the lines and had brought them in even before all the guards had been rounded up. While we were there, a corporal in our group crawled over the corpses and cut off a finger from one. He wanted an SS ring for a souvenir!

“Hey, you can’t do that,” a reporter yelled, but the deed was done. Later, there was an investigation of the shooting of the Dachau guards and an excerpt from the report on the coal yard reads, “I found 17 bodies … a finger had been completely severed from one body; from another body a finger had been severed at the second joint.” Maybe our corporal got two rings!

[Author’s note: Concentration camps were run and staffed by SS troops. SS is short for Schutzstaffel, which translates as protection squad. It was originally formed in the 1920s to protect Hitler at Nazi rallies, but after Heinrich Himmler was appointed Reichsführer SS in 1929, the goals and functions were constantly expanded to the point that the SS became one of the most evil and efficient killing machines the world has ever known. Concentration camp guards were originally organized as SS-Death’s Head units, and we had fought against Waffen-SS infantry troops in France and Germany.]

Private Fred Abraham was a C Company runner and interpreter for our commander, Bert Edmunds. Fred had been born and raised in Fulda, Germany. He said, “I had complete mastery of the German language, and I was able to read and translate the German paybooks (Soldbuch) which were written in the Gothic script and listed all units they had belonged to then and in the past.” Edmunds gave Fred a camera at Dachau and told him to take pictures.

Leonard Parker, a squad leader in our 3rd Platoon, wrote to his family: “We came upon the camp enclosure, and out of the gate came three prisoners…. The first one yelled at me, ‘Boy are we glad to see you,’ and you could have knocked me over with a feather because I hadn’t expected anyone to yell at me in English. He was a U.S. Army officer who had parachuted into France three months before D-Day on a secret mission and had been captured by the Gestapo and sent to Dachau.” (This was Lieutenant Rene J. Guiraud, a member of the Office of Strategic Services, who had been arrested as a spy, and who was one of six Americans liberated at Dachau.)

Leonard continued: “I guess the rest of the prisoners were waiting to see if we were all right, because then came a flood of human skeletons…. They fell on the ground at our feet and kissed our boots and grabbed for our hands and kissed them.”

Later, “A Jewish prisoner came up to me and asked me if it were true that there were Jewish soldiers in the American Army. When I told him I was a Jewish ‘unteroffizier,’ he nearly went mad. Soon, I had about 50 Jewish men and women around me hugging and kissing me.”

I should mention that, after the war, Leonard was one of C Company’s most distinguished alums. He finished his education at the University of Minnesota and M.I.T., and became an important architect in Minneapolis. Leonard Parker Associates designed buildings all over the world, and Leonard was professor emeritus at the university. He died in 2011. (He was originally Staff Sergeant Leonard S. Popuch in C Company, but after the war he changed his name to Parker.)

The Dachau Death Toll

I spent the rest of our daylight hours at Dachau maintaining a post on the west side of this huge camp, and during that time, I saw our men take only two guards to the rear. One building just over the wall from the coal yard had a large red cross painted on its roof. This was the hospital for the SS troops, and when I walked through it, there were no patients or medical personnel present. (Killingbeck found a Nazi flag in the hospital.)

I never did see the confinement area where the prisoners were held, the crematorium, or the mounds of naked corpses, which the soldiers found more horrifying than the boxcars.

Altogether at Dachau, 31,432 prisoners (3,918 of whom were French) were liberated alive in various stages of ill health, and thousands of emaciated corpses were found. The largest group of survivors was 9,082 Polish prisoners, including 96 women and 830 Catholic priests.

Many prisoners were so far gone they didn’t last long. The day after liberation, the Army conscripted adults in the town of Dachau, trucked them to the camp, and made them handle the bodies for burial. Lieutenant Marcus J. Smith, the Army doctor in charge of post-liberation Dachau, reported that after May 5, more than 3,000 bodies were cremated or buried.

“A Mind-Boggling Experience”

In an aside, in the 1990s I developed a warm friendship with Professor John M. Steiner at Sonoma State University. As a teenage prisoner from Prague, he had survived Theresienstadt, Auschwitz (where he lost his mother), and Dachau, and after the war he became a renowned Holocaust scholar. His Auschwitz number 168904 was tattooed on his left arm and he had worn his Dachau number 142095 on his uniform. After terrible experiences in various locations where he lost several toes, John had arrived at Dachau in a boxcar in January 1945, and speaking for the few survivors, brazenly told the SS to “either give us food or shoot us,” and they received some rations.

Steiner spent his four months at Dachau in the infirmary where more toes were amputated without anesthesia by fellow Czech prisoner Dr. Franz Blaha, who later testified at the Nuremberg Trials. (John told me he is the 19-year-old prisoner, who spoke Czech, German, and English, in the photo of the Dachau crematorium with Maj. Gen. Robert T. Frederick, commanding officer of the 45th Division. John died in 2014.)

For decades, I wondered why we never did guard duty that night at Dachau. I eventually learned that in the evening we who had relieved I Company in the afternoon were in turn relieved by them, and it seems the other platoons of C Company had hiked back to the town of Dachau and slept in homes. My platoon slept in the camp in a single-family home that had housed a senior SS officer’s family. Outside were flowerbeds and inside were upholstered furniture and framed pictures on the walls.

Most of us were about 19 years of age and knew we’d had a mind-boggling experience. We couldn’t get over the contrast between our quarters and the total depravity outside, and we talked until midnight.

Platoon Sergeant Ben Ewing remembered going upstairs in the home and finding a children’s nursery with toys on the floor and a crucifix on the wall. It was a tough day. That night I learned from the other guys that there was much of the camp I hadn’t seen, and I was determined to have a look around in the morning, but the opportunity never came. They wanted C Company back with the 1st Battalion, and we were out of there before dawn the next day to resume the attack on Munich.

Celebrations at an Allach Satellite Camp

We left the Dachau concentration camp before dawn on Monday, April 30, heading for Munich, and were hiking briskly when later that morning we came to a tall, picket fence. This turned out to be the perimeter of the Dachau satellite camp at Allach where the guards had fled. (Allach was seven miles from Dachau and was the largest of Dachau’s 94 subcamps located throughout Bavaria and down into Austria. Other parts of Allach were liberated that morning by 42nd Division troops.)

When the prisoners realized that we were the U.S. Army, the celebration began. We promptly gave them all of our K-rations, candy, and cigarettes. One GI threw a cigar over the fence and when the fight for it ended, the cigar was in shreds. We also retrieved potatoes from a nearby cellar and threw them over the fence to the prisoners. I spoke with an older prisoner from Warsaw who told me that he was a doctor. He said the guards had treated him deferentially, and he was not worked as hard.

Both Allach prisoners and conscripted laborers had worked in the nearby BMW plant, which had assembled Stuka engines for the Luftwaffe. In recent years, I met Peter Van Sehaik, who was from Rotterdam, and I learned that during the war he was a conscripted worker at this BMW plant. Peter told me that one day a prisoner asked him for food, and at great risk to himself and the prisoner, he left bread where he knew the prisoner would find it.

“Andy’s” Story

A great human interest story began at Allach with the liberation of Andor Deszöfe, a Jewish prisoner from Budapest, Hungary. He was befriended by Staff Sergeant William F. Sutton, a squad leader in our 3rd Platoon, and Bill talked for an hour that day with Andor, who spoke English well.

A few days later, Andor walked away from Allach and showed up at C Company in Munich, wanting to join the American Army and fight the Germans! Bill put a uniform on “Andy” who “served” four months in C Company until the day the regiment boarded the ship at Le Havre for the trip home. Bill considered smuggling him aboard but thought better of it.

Andor eventually emigrated to New York City where, aided by Paul Rodda (who had served as a private in Bill’s squad), he found and reconciled with his father (who had abandoned the family in Hungary). Andor married, raised a family, and had a successful business in New York City. He also reunited with Bill on many occasions there and in Georgia. Paul Rodda attended Andor’s wedding and remembered this from the reception: “I talked to a fellow who turned out to be an ex-SS trooper who had befriended Andy at Allach. Andy had kept in touch and had sent him airline tickets to come to the wedding. Go figure!”

[Author’s note: In 2009, I came across an Oregon woman on the Internet who was searching for her Jewish roots. She was looking for her father’s cousin, and the International Red Cross had tracked him from Hungary to Dachau, where he was known to have been liberated, but then the trail grew cold. The cousin’s name? Andor Deszöfe! By that time, Andor had died, but I put her in touch with Bill Sutton so she could contact the family.]

That afternoon at Allach, C Company was relieved by K Company, and we resumed the advance on Munich, which we approached with great apprehension. It was assumed Munich would be another Nuremberg, so we were delighted to learn the early units of the 45th and 42nd Divisions had met only scattered resistance that morning.

Later, I wrote to my folks, “We walked 18 kilometers from outside of Dachau to the middle of town, and I never took the gun off my shoulder.”

VE Day

At one point in Munich, we were walking on a boulevard that had a wide median strip that was strewn with German military paraphernalia. It seems that when the Wehrmacht and SS troops learned they would not have to defend the city, they changed into civvies and threw their uniforms and gear into the streets.

I remember April 30 as an exciting but easy day, and to my surprise I found in the morning report that Pfc. John W. Idol, Jr. was wounded. That would have been somewhere between Dachau and Munich (unless there’d been a delay in reporting). Like many of us, he had joined C Company in the last week of January 1945 when it was reformed (after losing so many members in Alsace in France), and he had gone unscathed through the Siegfried Line, Aschaffenburg, and Nuremberg. On what was effectively our final day in combat, Idol was C Company’s last casualty of World War II.

The next day, May 1, it was announced that the 45th Division would occupy Munich and our celebration began. On May 2, I wrote to my parents, “A guy just came in and said Generals Patch (Seventh Army) and Patton (Third Army) are about six blocks from here and are throwing the wildest party.”

On May 8, World War II in Europe officially ended. We occupied Munich for six weeks, and then after moving to the Augsburg area and Camp St. Louis near Reims, France, we sailed from Le Havre for the USA in early September.

The author was discharged from the Army on November 10, 1945. After the war, he attended Carleton College (BA) and Case Western Reserve University (MSSA) and had a career in insurance sales.

Between 1996 and 2003, Dan Dougherty published 23 issues of Second Platoon for veterans of C Company. Many issues contain articles and photos by soldiers, prisoners, and historians on the liberation of Dachau and Allach. Dan and his wife Norma have been married for 66 years and reside in Fairfield, California. They have three children and seven grandchildren.